Sophie Cave

Sophie's cave is a natural karst cave near Kirchahorn, a district of the Upper Franconia municipality of Ahorntal in the district of Bayreuth in Bavaria.

| Sophie Cave | |

|---|---|

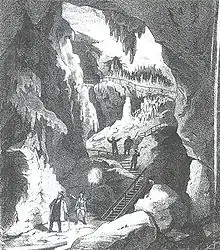

View over the elephant's ear into the Sophie Cave. | |

Sophie Cave | |

| 49°49′37″N 11°22′33″E | |

| Location | Franconian Switzerland |

| Country | Germany |

| History | |

| Associated people | 26,681 tourists (2012) |

| Specifications | |

| Capacity | 900 metres (3,000 ft) |

| Length | 220 metres (720 ft) |

The stalactite cave is located on the northwestern edge of the Ailsbach Valley, not far from Rabenstein Castle in Franconian Switzerland. With its three large sections and winding passages, Sophie Cave is considered one of the most beautiful show caves in Germany.

Location

Sophie Cave is located on the northwestern valley slope of the narrow, winding Ailsbach Valley near the community of Ahorntal in the Upper Franconia district of Bayreuth. The valley has many steep rock bastions and the highest density of caves in Franconian Switzerland. The entrance to the cave is at 411 m above sea level, the valley 375 m above sea level, and the Klausstein Chapel above it on the site of the former Ahorn Castle at 443 m above sea level. It can be reached from the parking lot at Rabenstein Castle west of the cave on a 650-meter-long footpath, and from the parking lot 30 meters below the cave, directly on Landesstraße 2185, a steep 120-meter-long path leads up.

Geology

- Tour of the Sophie Cave

Sophie Cave is located in fossil sponge reefs in the Franconian dolomite of the Jurassic Malm. The 18-meter wide, six-meter high[1] and uphill tapering entrance portal has a dome-shaped structure. The cave has dome-like halls, some of which are connected by narrow, winding passages. This is typical for caves in the Franconian dolomite. The cave is essentially drawn along the horizontal joints of the sponge reefs. These surface forms can be traced particularly well in the third section on the basis of joints. With a size of 42 × 25 × 11 meters[2] it is one of the largest Franconian cave rooms. Here, large rubble blocks have detached from the ceiling along the joints and cover the floor. The other two compartments also have rubble blocks, which in some places are covered by dripstones. The spatial appearance of the cave indicates a great age.

Origin

The cave was formed in standing groundwater along the largely horizontal joints. Carbonated water was able to penetrate through fine cracks and joints in the rock. Although carbonic acid is a relatively weak acid, it can dissolve limestone and dolomite rocks. Large cavities were formed by leaching along numerous cracks and fissures.[3] A deepening of the Ailsbachtal valley caused the water table to drop, exposing the cavities. Later, the rooms and passages were partially backfilled with sediments, partially separating the front compartments.

Cave complex

The Sophie Cave consists of a complex of a total of four caves: the entrance portal, which has always been known, the Ahornloch, the adjoining Kleinstein Cave, the actual Sophie Cave discovered in 1833 and the Hösch Cave, which was initially filled in. Together, the individual caves form the Kleinstein Cave complex or Sophie Cave. It has a length of about 900 meters,[2] with the actual Sophie Cave with its three sections being 500 meters long. In the cave register Franconian Alb, which has more than 3000 caves in an area of 6400 square kilometers, the Sophie Cave is registered as B 27 and the Hösch Cave connected to it as B 24.[4] The cave is designated as geotope 472H009[5] by the Bavarian State Office for the Environment. See also the list of geotopes in the district of Bayreuth.

Dripstones

Sophie Cave has rich and multiform stalactites. There are ceiling formations like stalactites and sinter tubes, floor formations like stalagmites and sinter basins, and beautiful wall sinter sections. Sintering occurs mainly in the first two sections, but is not completely absent in the third section. The rooms in front of the Sophie Cave, like the Ahornloch and the Klausstein Cave, have very few dripstones. In Sophie Cave there are sinter flags and sinter curtains, which occur on sloping ceilings and overhanging wall sections. The stalactites appear in a wide variety of colors. The transparent sinter tubes and pure white stalagmites are made of pure calcite. By contamination with iron oxide stalactites with yellow and brown colors appear. By manganese oxides some dripstones were colored black.

Fossil bones

Numerous bones of Pleistocene animals were found in the cave complex, with remains of the cave bear being the largest part. The bears used the Sophie cave during the winter rest to give birth to their young. Occasionally, animals died of old age or diseases. Over a long period of time, a large accumulation of bones accumulated.

The age of the bones in the Franconian Alb is estimated to be between 28,500 and 60,000 years.[6] This was the result of several radiocarbon dates from Franconian caves. Thus, the bear bones in Sophie Cave are mainly from the Würm Ice Age. There are no age datings about the Sophie Cave itself. In the first section of Sophie Cave, in addition to cave bear bones, there were also isolated remains of mammoth, woolly rhinoceros and reindeer. According to old cave reports, Sophie Cave must be considered outstanding in the Franconian Alps with regard to its numerous reindeer remains. However, most of the fossils found in Sophie Cave have been lost. Many of them were housed in the nearby Rabenstein Castle. Some are in the possession of the Palaeontological State Collection in Munich, such as a lower jaw fragment of a lion from the Pleistocene.

History

Early history

The antechamber of the Sophie Cave, the Ahornloch, was already used by prehistoric people. The name of the cave comes from the noble family of von und zu Ahorn, who are considered the first rulers of the Ahorn Valley and lived directly above the Ahornloch in Klausstein Castle. The parts of the cave that were accessible for thousands of years, the Ahornloch and the Klausstein Cave, were partially filled in by sedimentation over time. The backfill consisted of meter-thick layers of cave bear bones, bat droppings and remnants of human settlements from the Stone and Bronze Ages. In addition, there were frost fractures from the ceiling and sinter deposits. With this material, the low connecting passages between the halls were completely filled. As a result, the cave areas behind the closed parts were forgotten.

The Klausstein Cave takes its name from the Klausstein Chapel above it. There was a castle there, which was demolished. Neolithic period are the oldest finds, when man first became sedentary and practiced agriculture and animal husbandry. However, most of the finds come from the Hallstatt and La-Tène-Zeit. Ceramic sherds were predominantly found, and bronze jewelry was also reported. Whether the finds are based on a use of the cave as a human dwelling or whether cultic acts were performed there, could not be clarified so far.

First excavations

The bones and deposits found in the cave in the Middle Ages were sometimes attributed magical properties, which is why fossil animal bones and teeth were ground up and sold to pharmacies as medicinal powders. People tried to make gold from cave clay and dolomite ash. In 1490, Hans Breu from Bamberg wanted to extract saltpeter from phosphate-containing cave sediments in the Ahornloch, which was used for the production of black powder. The cave was mentioned for the first time in a document to this effect.[7] The enterprise failed, however, because no saltpeter could be extracted from the bottom sediments.

After this search for usable deposits, things quieted down again around the cave until about the second half of the 18th century. The pastor Johann Friedrich Esper, who is considered the founder of scientific cave exploration in Franconia, visited the Ahornloch in 1774 and 1778 and wrote a detailed description of the Ahornloch:[7]

"It is the highest northern rocky peak on which Klausstein rests, and below it the cave to be described now runs through the several lachter thick rock at a dizzying height. Over a path, which is almost impossible to climb from the valley, and from the top of the rock has a lot of dangerous, one approaches a twenty foot high rock wall, which by unknown coincidence has broken out like a shattered amphitheater in a width of several hundred feet and turns the open to the north. Four layers of rock are here on top of each other and the surface overhangs the baseline by several shoes, a thing that probably may have been caused by weathering... On the very bottom one sees with much care laid clefts, to which hunting dogs are said to have given the cause, which often got lost in this area while refereeing. Also, the water found in the depth of this crevice caused an experiment with ducks, they were let in, and they reappeared in the area of Streitberg. It is certain that these mountains have in their interior many stagnant lakes, and are crossed with interconnected channels.[...]" – Johan Friedrich Esper: Nach einem Bericht von 1778, Ansbach 1790[8]

During excavations in 1788 in the rear part of the maple hole, the Klausstein cave was rediscovered. In the following years, the partition wall to the maple hole was removed in order to create a more convenient entrance. It was also hoped to find something precious. No attention was paid to archaeological finds, such as cave bear bones. The excavated material was thrown into the shaft of the Klausstein cave.

During excavations in 1788 in the rear part of the maple hole, the Klausstein cave was rediscovered. In the following years, the partition wall to the maple hole was removed in order to create a more convenient entrance. It was also hoped to find something precious. No attention was paid to archaeological finds, such as cave bear bones. The excavated material was thrown into the shaft of the Klausstein cave.

Georg August Goldfuß describes the maple hole in one of his reports in 1810:

"The rock mass, where it has reached half of its height, is bent into a semicircle, the curvature of which may amount to several hundred shoes. Through a steep path one reaches the green place which the rock encloses, and now, under an overhang of it, the two entrances to the Klaustein cave are visible. Surrounded by traces of devastation, one timidly ventures into these gorges, in the interior of which nature has covered its workshop with night and horror to the human eye. [...]" –Georg August Goldfuß: Die Umgebung von Muggendorf. Erlangen 1810[9]

Discovery of the Sophie Cave

In 1833, the art gardener Michael Koch carried out expansion work on behalf of his employer, Reichsrat Count Franz Erwein von Schönborn-Wiesentheid, who owned the cave.[10] He wanted to create a new exit in the southeast of the cave. He pierced a sinter blanket and discovered fossil bones. Thereupon he crawled into a small room which, in contrast to the previously known parts of the cave, was equipped with sinter forms. While doing so, on February 16, 1833, he felt a strong draft of air in the rear, narrowed part, which blew towards him from a narrow crevice in the rock. Thereupon, he and estate workers removed rock debris and clay and widened the crevice. On February 18, 1833, he undertook a first inspection of this widened crevice with the count's patrimonial judge Schmelzing from Weiher and the miller Hösch from the nearby Neumühle. They discovered new cavities richly decorated with dripstones, the present Sophie Cave.[10] The excavated material was used to fill the shaft of the Klausstein Cave. The rooms separated from the Klausstein Cave by the overburden have a total length of about 200 meters and are now called Höschhöhle after the long-time owner of the Neumühle.[11]

Koch reported in detail to his count immediately after the discovery of the new cave rooms. To protect the cave, the count ordered its immediate closure. As a result, it could be preserved largely in its original state and was not deprived of its stalactite jewelry, as many other stalactite caves were. The discovery of the cave, which at that time was one of the most beautiful in Central Europe, was quickly spread in the newspapers.

In the newly discovered cave area about 40 partly sintered cave bear skulls, vertebrae, shoulder blades, limb bones and many individual teeth were found.[12] Cave hyena skulls were also found. The best preserved bones came to the museum of the adjacent Rabenstein Castle at the instigation of the count. The Geological and Mineralogical Institute of the University of Erlangen also received isolated relics. However, the finds that were housed in the castle at that time have disappeared.

The count visited the cave on June 21, 1833, with his eldest son Erwin and his wife Sophie (born Countess zu Eltz). He then named the cave Sophienhöhle in honor of his daughter-in-law.[10] He had the cave carefully prepared for visitors with stairways and pathways. During the development measures, the Maple Hole and the Klausstein Cave were completely leveled. After the discovery of the cave, numerous scholars came to study it more closely.

Johann Wilhelm Holle described the newly discovered cave quite euphorically in 1833 in Die neu entdeckte Kochshöhle oder die Höhlenkönigin im königl. Landgerichte Hollfeld-Waischfeld. Among other things, he reported that he had seen "the most famous caves in Europe, with these in terms of beauty and size stands above all comparison." About the cave he wrote: "Here nature seems to have poured out a whole cornucopia of beauty. The walls are dazzling white, as if covered with the finest alabaster; curtains of stalactites have formed in the center from the ceiling, and the edges seem to be lined with them. Waterfalls of 30 to 36 feet discharge on the right side; on the floor lie innumerable, cone-shaped, black-gray stalactites and quite petrified animals [...]."[13]

In 1834, the Sophie Cave was opened as a show cave.[14] During guided tours, magnesium light was first lit in front of the most beautiful stalactite formations. So-called Davy lamps, invented by Humphry Davy, were used to illuminate the cave. Later, carbide lamps were used.

Bone findings

Shortly after the discovery of the Sophie Cave in 1833, Professor Rudolph Wagner described the bone finds:

"In the depths on the ground there are a number of skulls, antlers and other bones covered by a relatively thin sinter crust, in part almost completely exposed and protected by overhanging rocks. Especially there are skulls, most perfectly preserved with teeth and all appendages, which cover the surface of a bone deposit probably extending far into the depth, and present themselves to the astonished observer. [...]" – Rudolph Wagner: Ueber die neu entdeckte Zoolithenhöhle bey Rabenstein. 1833[15]

In 1835, the paleobotanist Kaspar Sternberg wrote about the bone deposits in Sophie Cave:

"The Rabenstein Cave (Sophie Cave) in Franconia, which I visited on my return trip, is of far greater interest and is not yet sufficiently well known; it is difficult to find elsewhere the various species of animals that flee in ordinary life, so close and clearly recognizable next to each other [...]. On descending into the cave, one enters a spacious chamber, in the middle of which stalagmites have accumulated, and first encounters an upright standing stately race animal antler, which is very close to the antlers of the still living race animals; the head with the lower part of the two poles of the antler is covered with stalagmites, by which it is kept upright, several rungs are completely preserved. A few feet below lies an enormous basin of a mammoth embedded in this same stalagmite; and still several feet below, three cave bear heads protrude from the stalagmite, baring their teeth as if to seize their prey; and still a few paces away, two poles of a racing animal with a few rungs appear again, the lower ones covered with stalagmite." – Kasper Sternberg: Vortrag in Prag, 1835[16]

First measurements and further excavations

The cave parts connecting behind the maple hole had the names Klausstein Cave, Sophie Cave and Kochshöhle, after the discoverer. The name Kochshöhle disappeared around 1840, the name Klausstein Cave persisted alongside Sophie Cave until around 1900.[11] Theodor Rothbart published a portfolio of three lithographs depicting the three main sections of Sophie Cave in 1856. In 1902, the cave was surveyed for the first time by Major Adalbert Neischl with a total passage length of 284 meters.[2] This did not include some side passages, some of which were only made accessible later.

During renewed excavations in 1905 and 1906, a large number of remains of cave bears, cave lions, and hyenas were again found.[12] The total length of the cave, including the outer cave, was redetermined in 1966 by the Nuremberg Natural History Society to be 465 meters.[12] In 1971, the carbide lamps previously used in guided tours were replaced by electric lighting.[17] In the 1970s, the Hösch Cave, which had been closed and cut off during development work in 1833, was rediscovered. In 1997, the entire cave had to be remeasured again, as further discoveries were made in the course of more recent research work by speleologists from Bayreuth and Nuremberg. The new survey, together with the Hösch Cave, resulted in a length of about 900 meters.[2] In late summer of 2000, the show cave operation, with 34,000 visitors a year at last count, was discontinued due to safety deficiencies.

Present

The current owners are Reiner Haas and Wolfgang Deß from Nuremberg, who bought the cave together with Rabenstein Castle in December 2000. As part of a renovation in 2002, the maple hole, which had been open to the public until then, was barred.

In 2011, over 8,000 bones were secured in a side cave during sifting operations, from which the skeleton of a cave bear was assembled and placed in a display case in the second vestibule. The almost complete cave bear skeleton, to which the cave operators gave the name Benno, is considered the most complete in the world.[18]

In 2012, the lighting system of the cave was completely renewed with LEDs.[19] Since LED lamps produce less UV light than conventional lamps, plant growth in the cave is reduced. The mosses and ferns created by the old lamps were removed except for a few voucher specimens. A modern security system against burglary and vandalism was also installed during the remodeling.[19]

Description

The path leads through a very narrow passage about three meters long to a platform in the upper part of the first section of the cave. Directly in front of the path, which leads there to the left, is the "Elephant's Ear", a free-hanging sinter plume more than one meter long. As a counterpart, a stalagmite has formed at the bottom, the "Beehive". The path then passes the "Oriental City" and turns right in a semicircle. The "Oriental City" is located halfway up on the left in a small cavity and consists of numerous candle stalagmites. Afterwards a staircase leads more than ten meters down, where a cave bear of the small cave bear race Ursus spelaeus eremus,[20] assembled from bones, can be found. The sintering on the right wall reminds of a waterfall and gave reason to give the formation the same name. On the ceiling there are sinter flags, sporadically also sinter tubes. On the floor there are prehistoric and protohistoric bones covered with sinter mass, especially reindeer antler poles and a mammoth basin deposited in one place by the Cromagnon people of the Gravettian, probably in a shamanic context in the cave. Stalagmites with drop funnels have also formed in several places.

A grate leads into the second section. Several sintering basins of different sizes can be seen on the left and right. Several sinter bowls with diameters of a few millimeters are located next to them. These formations are formed by slowly draining water on the inclined sinter surfaces. On the left follows the "Millionaire", the largest stalactite in the cave. At the base this stalagmite has a diameter of more than two meters; it is about 2.4 meters high.[1] The name derives from the formerly assumed age. However, this was set much too high. The stalagmite is fed by a large sinter plume, the chandelier. In the right rear part there is another floor stalactite, which is, however, somewhat smaller than the millionaire and is called "Eisberg" or "Kleiner Millionär". Other sintered plumes, some over a meter long, have formed on the ceiling. One particularly striking one is called "Adler".

The path goes past the "Millionär" steadily uphill. Through a very narrow passage you come to the third section, the largest cavity of the cave complex. Here sintering is almost completely absent. Only in some places dripstones have formed, including a large cone-shaped stalagmite. On one wall, descending water has created a large sinter formation called "Kanzel mit Madonna". In this room, five large boulders lie on the floor, which have detached from the ceiling and are already partly sintered over. On the ceiling, an area is secured with large iron anchor rods to prevent further rockfall. On the ceiling run several parallel fissures, which are overgrown with sinter. The path describes a large circle in this section and leads to the exit.

Individual side passages are not accessible. Also, parts of the old guide path are no longer used. There are also dripstone formations, for example cauliflower sinter and the sintered-in pelvis fragment of a cave bear. The Maple Hole and the Klausstein Cave were changed during the various excavations. The ground was ransacked during the search work and later leveled, partitions were removed or widened, shafts were filled with excavation material and dripstones were removed. The cave is closed. It can be entered only by experienced cave climbers. From the first section two openings lead to a small side cave, which can be seen but not entered. Because of the numerous bone finds of Ursus spelaeus (cave bear) it is called bear cave. It is unclear how the cave bears got in there, since the present entrance was only uncovered in the 19th century and the assignment of rock crevices to an entrance passable for bears at that time does not seem possible.

The area is designated as a ground monument (D-4-6134-0059) by the Bavarian State Office for Monument Protection (BLfD).

Flora and fauna

Fauna

Despite the adverse living conditions, year-round nine degrees Celsius and darkness except for the lighting during the guided tours, the Sophie Cave is home to a diverse fauna. 35 different animal species have been identified so far,[21] making Sophie Cave one of the most fauna-rich caves in the Franconian Alb. These are different species of spiders and insects. However, not all animals encountered in the cave are true cave animals. So-called trogloxenes, animals foreign to the cave, get into the cave by chance and perish soon after.

Subtroglophilous animals that are only in the cave during certain developmental phases or seasons are found with some regularity. The buckthorn moth Triphosa dubitata belongs to this group. This moth seeks out the Sophie Cave as early as late summer, often to overwinter in large numbers in the area near the entrance. Individual specimens spend up to ten months in the cave. In spring, the surviving moths leave the cave to lay their eggs.

Eutroglophiles, cave lovers, include most of the animals found in Sophie Cave. They spend their entire lives in the cave. However, they can also exist in the outside world. This group includes, above all, the numerous springtails. These one to two millimeter long animals belong to the primordial insects and live mainly on the surface of the numerous water and sinter pools. With their fork-shaped jumping apparatus, they can cover distances that exceed their own size by more than ten times. Another species is the cave spider Meta menardi. This often lives in sheltered places of the cave ceiling. There, more than a hundred young spiders often hatch from centimeter-sized spherical egg cocoons. Some of these young remain in the cave and grow there until sexual maturity, others leave Sophie Cave to find new habitats in the vicinity of the cave entrance. Sophie Cave is also home to the larvae of the fungus gnat Speolepta leptogaster. They are known exclusively from caves and have back-formed eyes that are fully developed in adult insects. The larvae, which are only a few millimeters in size, live on a delicate web of filaments that are beaded with droplets of mucus.

Sophie Cave is one of the few caves in Franconia that is also home to real cave animals. These are called troglobionts and have developed characteristics in the course of evolution that enable them to live permanently in the cave. So far, twelve of these animal species have been identified in Franconian caves, two of which live in Sophie Cave.[2] The food requirements of these animals are greatly minimized; they digest almost anything with even a very low nutrient content. One species is a microscopic crustacean of the genus Bathynella. The second species is the pigmentless flatworm Phagocatta vitta. In the caves of the Franconian Alb, it has so far only been found in the Sophie Cave.

Flora

In the Sophie Cave, since the first installation of electric light in 1971, a very conspicuous and diverse plant community has formed, the so-called lamp flora. This is most strongly represented near the sources of illumination. In the relatively weak light conditions, mainly algae and mosses can thrive. Much more demanding flowering plants have hardly any chance of survival in these light conditions and rarely appear in the form of pale, short-lived seedlings. The plants differ in many respects from their conspecifics on the earth's surface, as they live on the edge of subsistence. In the case of the mosses, the stems are usually elongated, loosely leafy, and the leaf ends have overlong tips.

The lamp flora in the Sophie Cave is subject to certain regularities in its development. Light-sufficient algae prove to be pioneer plants that settle even at a greater distance from a light source. These are later joined by various species of moss. In the Sophie Cave, the light-sufficient Fissidens taxifolius is the most common. It forms extensive moss lawns.

The plants encountered today all appeared after electric lighting was installed. To minimize plant growth on the dripstones, lighting outside the guides is kept to a minimum. During the renovation phase from 2000 to 2002, some of the plant growth was removed. Before that, there were already fungi that had penetrated far into the depths of Sophie Cave with their light-independent way of life. These fungi were mainly found on the former wooden railing of the guide path and other organic remains. In caves, fungi can grow out of their organic culture medium due to the high humidity and spread to the surrounding inorganic surfaces with so-called rhizomorphs. These rhizomorphs, some of which cover very large areas, can even be found in Sophie Cave on sinter flags in the ceiling area of the second section. The special cave climate leads to different growth forms of the fungi, so that their appearance is very different. The mushrooms play an important role as a food source for many cave animals.

Tourism

The guided tours in the Sophie Cave go over well passable paths and stairs, which were all renewed from the year 2000, into the individual departments and past the stalactite formations. The guide path is used in the Maple Hole, in the Klausstein Cave and in the first two sections of the Sophien Cave as an outward and return path. In the third section it is laid out as a circular route. A guided tour lasts about 40 minutes. The distance covered is about 220 meters. Guided tours take place all year round. During the summer months, concerts are held in the Klausstein Cave.

Since the reopening in 2002, a multimedia show (Sophie at night) is offered in the cave. It takes place on Saturdays after the guided tour in the evening. It also includes the area in front of the cave with a bonfire. Nature films are shown in the maple hole. During the multimedia show, each visitor can move freely in the cave to look at the stalactite formations illuminated in different colors, whose lighting changes constantly. This is accompanied by a sound show.[22]

In the years 2008 to 2012, the average number of visitors was 29,002. This value places the show cave in the middle range of show caves in Germany. In 2008, 31,649 people visited the cave (the highest number since the reopening in 2002). In 2012, there were 26,681 visitors.

See also

References

- Friedrich Herrmann: Höhlen der Fränkischen und Hersbrucker Schweiz. p. 80.

- Hardy Schabdach: Unterirdische Welten – Höhlen der Fränkischen- und Hersbrucker-Schweiz, p. 48.

- Hardy Schabdach: Die Sophienhöhle im Ailsbachtal, S. 9.

- Stephan Lang: Höhlen in Franken – Wanderführer in die Unterwelt der Fränkischen Schweiz mit neuen Touren, S. 61–63.

- Geotop: Sophienhöhle bei Rabenstein (Schauhöhle). (PDF; 284 kB) abgerufen am 26. August 2013

- Martina Pacher, Anthony J. Stuart: Extinction chronology and palaeobiology of the cave bear ( Ursus spelaeus ). In: Boreas. Band 38, Nr. 2, Mai 2009, ISSN 0300-9483, S. 189–206, doi:10.1111/j.1502-3885.2008.00071.x (Online [Retrieved 2020-11-10]).

- Hardy Schabdach: Die Sophienhöhle im Ailsbachtal, S. 11.

- Johan Friedrich Esper: Kurze Beschreibung der in den Osteolithen Grüften bey Gailenreuth ohnweit Muggendorf im Baireutischen neuerlich entdeckten Merkwürdigkeiten. Ansbach 1790, S. 77–105.

- Georg August Goldfuß: Die Umgebung von Muggendorf – Ein Taschenbuch für Freunde der Natur und Alterthumskunde. Erlangen 1810, S. 114.

- Hardy Schabdach: Die Sophienhöhle im Ailsbachtal. p. 13.

- Brigitte Kaulich: Vom Land im Gebirg zur Fränkischen Schweiz, Erlangen 1992.

- Friedrich Herrmann: Höhlen der Fränkischen und Hersbrucker Schweiz. p. 81.

- Johann Wilhelm Holle: Die neu entdeckte Kochshöhle oder die Höhlenkönigin im königl. Landgerichte Hollfeld-Waischfeld. Bayerische Annalen, Nr. 26, pp. 197–198.

- Hans Binder, Anke Luz, Hans Martin Luz: Schauhöhlen in Deutschland. p. 74.

- Rudolph Wagner: Ueber die neu entdeckte Zoolithenhöhle bey Rabenstein. In: Bayerische Annalen, Nr. 47, 1833, pp. 313–315.

- Vortrag von Kaspar Sternberg in der allgemeinen Versammlung des böhmischen Museums 1835 in Prag.

- Hardy Schabdach: Die Sophienhöhle im Ailsbachtal. p. 33.

- „Benno“ ist wieder komplett / Europaweit einziges vollständige Höhlenbärenskelett in der Sophienhöhle bei Ahorntal entdeckt. In: Koschyk unterwegs. 8. August 2011, retrieved 2020-11-10.

- Thomas Weichert: Neue Lichteffekte setzen „Höhlenkönigin“ in Szene. In: nordbayern.de. 21. Juli 2012, retrieved 2012-08-29.

- Cajus Diedrich: Ice Age geomorphological Ahorn Valley and Ailsbach River terrace evolution – and its importance for the cave use possibilities by cave bears, top predators (hyenas, wolves and lions) and humans (Neanderthals, Late Palaeolithics) in the Frankonian Karst: Case studies in the Sophie’s Cave near Kirchahorn, Bavaria. In: E&G Quaternary Science Journal. In: . Band 62, Nr. 2, 20. Dezember 2013, ISSN 2199-9090, pp. 162–174, doi:10.3285/eg.62.2.07 (Online [retrieved 2020-11-10]).

- Hardy Schabdach: Die Sophienhöhle im Ailsbachtal. p. 29.

- "Sophie at night" - Multimediashow in der Sophienhöhle. In: mamilade.de. Retrieved 2020-11-10.

Bibliography

- Cajus Diedrich: Sophie's Cave (Germany) - a Late Pleistocene Cave Bear Den. In: Famous Planet Earth Caves, Vol. 1. 2015. DOI:10.2174/97816810800001150101, https://benthambooks.com/book/9781681080000/

- Cajus Diedrich: Ice Age geomorphological Ahorn Valley and Ailsbach River terrace evolution and its importance for the cave use possibilities by cave bears, top predators (hyenas, wolves and lions) and humans (Late Magdalénians) in the Frankonia Karst – case studies in the Sophie's Cave near Kirchahorn, Bavaria. Quaternary Science Journal, 2013, 62 (2), 162–174. Open access: http://issuu.com/geozon/docs/e-38-g-quaternary-science-journal-vol-62-no-2

- Hans Binder, Anke Luz, Hans Martin Luz: Schauhöhlen in Deutschland. Aegis Verlag, Ulm 1993, ISBN 3-87005-040-3, pp. 74–75.

- Friedrich Herrmann: Höhlen der Fränkischen und Hersbrucker Schweiz. 2., verb. Aufl. Verlag Hans Carl, Nürnberg 1991, ISBN 3-418-00356-7, pp. 80–83.

- Brigitte Kaulich: Die Sophienhöhle bei Rabenstein. In: Vom Land im Gebirg zur Fränkischen Schweiz. Eine Landschaft wird entdeckt. Verlag Palm und Enke, Erlangen 1992, ISBN 3-7896-0511-5, pp. 255–263.

- Stephan Kempe: Höhlen. Welt voller Geheimnisse. HB Verlags- und Vertriebs-Gesellschaft, Hamburg 1997, ISBN 3-616-06739-1, pp. 100–101 (=Reihe: HB Bildatlas. Sonderausgabe).

- Stephan Lang: Höhlen in Franken. Ein Wanderführer in die Unterwelt der Fränkischen Schweiz. Überarb. und erw. Aufl. Verlag Hans Carl, Nürnberg 2006, ISBN 978-3-418-00385-6, pp. 61–64.

- Hardy Schabdach: Die Sophienhöhle im Ailsbachtal. Wunderwelt unter Tage. (Hauptquelle für Flora und Fauna) Verlag Reinhold Lippert, Ebermannstadt 1998, ISBN 3-930125-02-1.

- Hardy Schabdach: Unterirdische Welten. Höhlen der Fränkischen und Hersbrucker Schweiz. Verlag Reinhold Lippert, Ebermannstadt 2000, ISBN 3-930125-05-6, pp. 47–49.

- Helmut Seitz: Schaubergwerke, Höhlen und Kavernen in Bayern. Ein Ausflugsführer in die Unterwelt. Rosenheimer Verlagshaus, Rosenheim 1993, ISBN 3-475-52750-2, pp. 47–49.