Constitutional Court of Korea

| Constitutional Court of Korea | |

|---|---|

| 대한민국 헌법재판소 | |

Emblem of the Constitutional Court of Korea | |

.jpg.webp) Constitutional Court of Korea in Jongno, Seoul | |

| Established | 1988 |

| Location | Jongno, Seoul |

| Composition method | Appointed by President upon nomination of equal portions from National Assembly, Supreme Court Chief Justice and the President |

| Authorized by | Constitution of South Korea Chapter VI |

| Judge term length | Six years, renewable (mandatory retirement at the age of 70) |

| Number of positions | 9 (by constitution) |

| Website | ccourt |

| President | |

| Currently | Yoo Nam-seok |

| Since | 21 September 2018 |

| Constitutional Court of Korea | |

Logo of the Constitutional Court of Korea | |

| Korean name | |

|---|---|

| Hangul | |

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Heonbeop Jaepanso |

| McCune–Reischauer | Hŏnpŏp Chaep'anso |

|

|---|

|

|

The Constitutional Court of Korea (Korean: 헌법재판소; Hanja: 憲法裁判所; RR: Heonbeop Jaepanso) is one of the highest courts—along with the Supreme Court—in South Korea's judiciary that exercises constitutional review, seated in Jongno, Seoul. The South Korean Constitution vests judicial power in courts composed of judges, which establishes the ordinary-court system, but also separates an independent constitutional court and grants it exclusive jurisdiction over matters of constitutionality. Specifically, Chapter VI Article 111(1) of the South Korean Constitution specifies the following cases to be exclusively reviewed by the Constitutional Court:[1]

- The constitutionality of a law upon the request of the courts;

- Impeachment;

- Dissolution of a political party;

- Competence disputes between State agencies, between State agencies and local governments, and between local governments; and

- Constitutional complaints as prescribed by [the Constitutional Court] Act.

Article 111(2) states that the Constitutional Court shall consist of nine justices qualified to be court judges, all of whom shall be appointed by the president of South Korea. Even though all nine justices must be appointed by the president, Article 111(3) states that the National Assembly and the Chief Justice shall nominate three justices each, which implies the remaining three are nominated by the president of South Korea. Article 111(4) states that the candidate for the president of the Constitutional Court must obtain the approval of the National Assembly before the President appoints them.

The South Korean Constitution broadly delineates the roles of courts, both ordinary courts and the Constitutional Court, and entrusts the National Assembly to legislate the specifics of their functions. The National Assembly, soon after the tenth constitutional amendment that ended decades of dictatorship in South Korea, passed the Constitutional Court Act (Korean: 헌법재판소법), which spells out a detailed organizational structure of the Court, establishes the hierarchy of judicial officers and their roles within the Court, and most importantly, provides ways in which people of Korea can appeal to the Court. Unlike other constitutional courts (most notably Federal Constitutional Court of Germany), a party may file a constitutional complaint directly with the Court, without having to exhaust all other legal recourse, when a particular statute infringes upon his or her constitutional rights.

Although the Constitutional Court and the Supreme Court are treated as coequal (see Article 15 of the Constitutional Court Act[2]), the two courts have persistently come into conflict with each other over which of them is the final arbiter of the meaning of the Constitution. The Supreme Court, which is supposed to be the court of last resort, has criticized the Constitutional Court for attempting to upend the "three-tiered trial" system—referring to the conventional practice of allowing appeals up to twice—and placing itself above the Supreme Court. In 2022, the relationship between the two high courts seemingly came to a head when the Constitutional Court overturned a Supreme Court decision without declaring the relevant statute unconstitutional, holding that the statute itself does not violate the Constitution but its particular application does. The Supreme Court publicly denounced the ruling, saying that it entails the unacceptable implication that the ordinary courts' decisions fall under the Constitutional Court's jurisdiction, which subjugates the Supreme Court to the Constitutional Court.

The Constitutional Court of Korea is the seat of the Permanent Secretariat for Research and Development of the Association of Asian Constitutional Courts and Equivalent Institutions.

History

After regaining independence from the Japanese colonial rule in 1945, there were multiple attempts to establish an independent constitutional court to exercise judicial review. Members of the Constitutional Drafting Committee prior to the first republic debated whether Korea's system of constitutional review should be modeled after the United States or continental Europe. Kwon Seung-ryul's proposal followed the American judicial system where only the Supreme Court interprets the constitution, whereas Yoo Jin-oh's proposal followed the European model with a constitutional court. The Constitutional Committee (Korean: 헌법위원회) of the first republic was the result of a compromise between the two proposals. According to the 1948 Constitution, the vice president chaired the Constitutional Committee, the National Assembly appointed five assemblymen as committee members (after the 1952 constitutional amendment, three from the House of Representatives and two from the House of Councillors), and the chief justice of the Supreme Court recommended five from the Supreme Court justices to the committee.

Syngman Rhee's dictatorial rule, however, sabotaged the committee's normal operation, and as a result, the committee was able to adjudicate only six cases, two of which ruled the statutes at issue unconstitutional. The 1952 constitutional amendment established a bicameral legislature but Syngman Rhee's regime, until its demise, refused to enact the House of Councillors election law. As a result, the upper house, required for the Constitutional Committee to function, was never formed, and the Constitutional Committee soon ground to a halt.[3]

_5.16_%EA%B5%B0%EC%82%AC%ED%98%81%EB%AA%85_(5591601384).jpg.webp)

After Rhee was overthrown in the April Revolution, the second republic was established through a constitutional amendment transitioning from a presidential to parliamentary system. As a part of the amendment, the Constitutional Court (Korean: 헌법재판소) was established to replace the now-defunct Committee. According to the 1960 constitutional amendment, the President, House of Councillors and the Supreme Court each designated three Constitutional Court judges. Although legislation to form the Court was passed in April 1961, the Court never came into existence as Park Chung Hee, who later became president, launched a coup the following month and suspended the constitution.[4]

After the nominal dissolution of the military junta, President Park Chung Hee jammed through the 1962 constitutional amendment, which conferred the power to review cases on constitutionality on the Supreme Court and dissolved the Constitutional Court. Following the constitutional mandate in 1971, the Supreme Court unanimously struck down Article 2 of the National Compensation Act (Korean: 국가배상법), which restricted state liability for compensating injured soldiers while serving the country. Enraged by the decision, in the following year, Park pushed through yet another constitutional amendment, establishing the Yushin Constitution, a notoriously oppressive document that gave the president sweeping executive and legislative powers. The Yushin Constitution had an article that expressly overturned the 1971 Supreme Court decision on the National Compensation Act. Furthermore, the Supreme Court justices involved in the decision were refused reappointment and forced into retirement.

The Yushin Constitution (and the successive constitution of the fifth republic) also re-established the Constitutional Committee, but required an ordinary court to submit a formal request for constitutional review before the committee could exercise its judicial power. Since the Supreme Court was wary of retaliation as happened in 1971, it forbade courts from making such requests, rendering the Constitutional Committee powerless.[5]

The June Struggle in 1987 led to the 1987 constitutional amendment, which finally democratized Korea and ushered in the sixth republic, which continues to this day as of January 2023. The 1987 Constitution established the Constitutional Court of Korea as we know it and empowered the Court to review matters on constitutionality.[6] Following such will of the South Korean people, the Constitutional Court has made significant landmark decisions in contemporary history of South Korea. Renowned latest decisions of the Court include the decriminalization of abortion and the impeachment of Park Geun-hye.[7]

Status

The current judicial system of South Korea, especially the Constitutional Court of Korea, was influenced by the Austrian judicial system.[8] While Austria has three apex courts, whose jurisdiction is defined in different chapters of the Austrian constitution,[9] the Constitution of South Korea[10] only establishes two apex courts. Ordinary courts with the Supreme Court of Korea at the top is established by Article 101(2) under Chapter 5 'Courts' (Korean: 법원), while the Constitutional Court of Korea is the one and only highest constitutional court established by Article 111(1) Chapter 6 'Constitutional Court' (Korean: 헌법재판소).

The drafters of the Constitution tried to emphasize that the Constitutional Court does not belong to the ordinary-court system by using different but synonymous words. The term 'jaepanso (Korean: 재판소; Korean pronunciation: [tɕɛpʰanso])', meaning court, was used to describe the Constitutional Court, while 'beobwon (Korean: 법원; Korean pronunciation: [pʌbwʌn])' was used to represent the ordinary courts. The equal status of the Constitutional Court and the Supreme Court is guaranteed by Article 15 of the Constitutional Court Act, which states that the President and the Associate Justices of the Constitutional Court should be treated the same as the Chief Justice and the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court, respectively.[11]

Composition

Justices

Article 111 of the Constitution of the Republic of Korea stipulates the size of the Constitutional Court and the nomination and appointment procedure for its Justices.[10] The Court is composed of nine Constitutional Court Justices (Korean: 헌법재판소 재판관), and the President of South Korea formally appoints each Justice.[10] However, Article 111(3) of the Constitution divides the power to nominate persons for appointment into equal thirds among the President, the National Assembly, and the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Korea.[10] Thus, the President has the power to both nominate and appoint three of the Constitutional Court's nine Justices, but the President must appoint the remaining six Justices from persons selected by the National Assembly or the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. This appointment structure reflects the civil law tradition of regarding ordinary courts as heart of conventional judiciary, since the President of South Korea represents executive branch, and the National Assembly represents legislative branch, while the Supreme Court Chief Justice represents judicial branch of the South Korean government. However, it is clear that both the Supreme Court and the Constitutional Court generally regard the power of the Constitutional Court as essentially a kind of judicial power.[12]

In order for a person to be appointed as a Constitutional Court Justice, Article 5(1) of the Constitutional Court Act requires that the person must be at least 40 years old, qualified as attorney at law, and have more than 15 years of career experience in legal practice or legal academia.[11]

While exact internal procedure for the nomination of Constitutional Court Justices is not stipulated by statutes, nomination of the three Justices from the National Assembly is usually determined by political negotiations between the ruling party in the Assembly and the first opposition party. The second opposition party also plays a role in this process when it has sufficient membership in the Assembly. When the second opposition party does not have sufficient membership in the Assembly to formally participate in nomination process, the ruling party nominates one Justice, and the first opposition party nominates another. The remaining nomination is shared between the two parties, decided by negotiation or by election when the negotiation fails. For example, former Justice Kang Il-won was nominated by the National Assembly according to negotiations between the ruling Saenuri Party and the first opposition Democratic United Party in 2012. When the second opposition party is big enough to formally participate in the appointment process, it nominates the third Justice. Current Justice Lee Young-jin is example of Justice nominated from the National Assembly by the second opposition party; the Bareunmirae Party nominated him in 2018.

Notably, Article 6(2) of the Constitutional Court Act states there should be "confirmation hearings of the National Assembly" (Korean: 국회 인사청문회) for all Constitutional Court Justices before appointment or nomination.[11] However, this procedure has been interpreted as non-binding where the Constitution itself does not require the National Assembly's confirmation or consent for the nomination or appointment.[13] Thus, the National Assembly cannot use the confirmation hearing process to block the nominations advanced by the President or the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, or the President's appointment of such nominees.

Council of Constitutional Court Justices

The "Council of Constitutional Court Justices" (Korean: 재판관회의) is established according to article 16(1) of the Constitutional Court Act.[11] It is composed of all nine Justices (including the President of the Constitutional Court as permanent presiding chair), and can make decisions by simple majority among a quorum of two-thirds of all Supreme Court Justices, according to article 16(2) and (3) of the Act.[11] The main role of the council is supervisory functions for the President of the Court's power of court administration, such as the appointment of the Secretary General, the Vice Secretary General, Rapporteur Judges and other high-ranking officers over Grade III. Other issues requiring supervisory functions of the Council include making interior procedural rules and planning on fiscal issues.

President of the Constitutional Court

Article 111(4) empowers the President of South Korea to appoint the President of the Constitutional Court of Korea among nine Constitutional Court Justices, with consent the National Assembly. By article 12(3) of the Constitutional Court Act, President of the Court represents the Court and supervises court administration. Also by article 16(1), the President of the Court is chair of the Council of Constitutional Court Justices. Finally, by article 22 of the Constitutional Court Act, the President of the Court always becomes presiding member of the Full bench (Korean: 전원재판부) composed of all nine Constitutional Court Justices.

Tenure

Article 112(1) of the Constitution and article 7 of the Constitutional Court Act provides the term of associate Justice as renewable six-year up to mandatory retirement age of 70. However, there's only two Justices who attempted to renew their term by reappointment,[14] because renewing attempt can harm judicial independence of the Constitutional Court. During the term, according to article 112(1) and 112(2) of the Constitution, Justices shall not be expelled from office unless by impeachment or a sentence of imprisonment, and they shall not join any political party, nor shall participate in political activities to protect political neutrality of the Court.

One of sophisticated issue on the Court's tenure system is term length of the President of the Court, since the Constitution and the Act never states about exact term of the President. Shortly, the President of the Court who was newly appointed simultaneously as both Justice and the President can have full six-year term as one of the Justice, while the President of the Court who was appointed during term as Justice can only serve as the President during remaining term as Justice. For more information, see President of the Constitutional Court of Korea.

Current justices

| Name | Born | Appointed by | Recommended by | Education | First day / Length of service |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yoo Nam-seok (President) | May 1, 1957 (age 66) in Mokpo | Moon Jae-in | (Directly) | Seoul National University | November 11, 2017 / 5 years, 11 months |

| Lee Eunae | May 21, 1966 (age 57) in Gwangju | Moon Jae-in | Chief Justice (Kim Myeong-soo) | Seoul National University | September 21, 2018 / 5 years, 1 month |

| Lee Jongseok | February 21, 1961 (age 62) in Chilgok | Moon Jae-in | National Assembly (Liberty Korea) | Seoul National University | October 18, 2018 / 5 years |

| Lee Youngjin | July 25, 1961 / (age 62) in Hongseong | Moon Jae-in | National Assembly (Bareunmirae) | Sungkyunkwan University | October 18, 2018 / 5 years |

| Kim Kiyoung | April 9, 1968 (age 55) in Hongseong | Moon Jae-in | National Assembly (Democratic) | Seoul National University | October 18, 2018 / 5 years |

| Moon Hyungbae | February 11, 1966 (age 57) in Hadong | Moon Jae-in | (Directly) | Seoul National University | April 19, 2019 / 4 years, 6 months |

| Lee Mison | January 18, 1970 (age 53) in Hwacheon | Moon Jae-in | (Directly) | Pusan National University | April 19, 2019 / 4 years, 6 months |

| Kim Hyungdu | October 17, 1965 (age 58) in Jeonju | Yoon Suk Yeol | Chief Justice (Kim Myeong-soo) | Seoul National University | March 31, 2023 / 6 months |

| Jung Jungmi | May 24, 1969 (age 54) in Seoul | Yoon Suk Yeol | Chief Justice (Kim Myeong-soo) | Seoul National University | April 17, 2023 / 6 months |

Organization

Rapporteur Judges

Rapporteur Judges (Korean: 헌법연구관, formerly known as 'Constitutional Research Officers') are officials supporting nine Justices in the Court. They exercise investigation and research for review and adjudication of cases, to prepare memoranda and draft decisions, which makes them as kind of judicial assistant (such as Conseillers référendaires[15] in French Cour de cassation or Gerichtsschreiber[16] in Swiss Bundesgericht usually working for 5 to 10 years or more until retirement, but not as law clerks in United States Supreme Court working for 1 to 2 years as intern[17]).

Rapporteur Judges are appointed by President of the Court with consent of Council of Justices, under article 16(4) and 19(3) of the Act, and serve for renewable ten-year terms, which is same tenure system as lower ordinary court Judges (Korean: 판사) in South Korea. It is noticeable that Rapporteur Judges serve longer than Justices in Constitutional Court, and paid as same as lower ordinary court Judges, since these professional assistants are designed to ensure continuity of constitutional adjudication in South Korea. Some of Rapporteur Judges position is filled with lower ordinary court Judges or Prosecutors seconded from outside of the Constitutional Court for 1 to 2 years, to enhance diversity and insight of the Court according to article 19(9) of the Act. Other than Rapporteur Judges, there are 'Constitutional Researchers' (Korean: 헌법연구원) and 'Academic Advisors' (Korean: 헌법연구위원) at the Court, working for 2 to 5 years to assist research on academic issues mainly on comparative law related to the Court's on-going cases by article 19-3 of the Act.

Department of Court Administration

The Court's administrative affairs are managed autonomously inside the Court, by apparatus called 'Department of Court Administration' (DCA, Korean: 헌법재판소사무처). The department is led by the 'Secretary General' (Korean: 사무처장), currently Park Jong Mun, under direction of the President of the Court, provided with consent of 'Council of Justices' (Korean: 재판관회의) in some of important issues under article 16 and 17 of the Constitutional Court Act. The Secretary General is treated as same level as other Ministers at State Council in executive branch of South Korean government, by article 18(1) of the Act. The Deputy Secretary General (Korean: 사무차장) is appointed usually from the senior Rapporteur Judges and treated as same level as other Vice-Ministers. The department implements decisions of the Council of Constitutional Court Justices and operates various issues of court administration, including fiscal and human resource issues or other information technology services of the Court. It has also professional team for supporting international relations of the Court, including Venice commission and Association of Asian Constitutional Courts and Equivalent Institutions.

Constitutional Research Institute

Constitutional Research Institute (Korean: 헌법재판연구원) is the Constitutional Court's own institute established by article 19-4 of the Constitutional Court Act in year 2011, for research on fundamental academic issues concerning comparative law and original legal theories for South Korean Constitution. It also has function for training newly appointed officials of the Court and educating public on constitution. Professors at the Institute are recruited mainly from PhD degree holders educated from foreign countries, and their research and education programs are supervised by senior Rapporteur Judges as manager seconded from the Court. The institute is currently located in Gangnam, Seoul.[18]

Building

Current buildings of the Constitutional Court of Korea, seated in Jae-dong, Jongno-gu of Seoul near Anguk station of Seoul Subway Line 3, is divided into Courthouse and the Annex. The five-story main building for Courthouse is designed in neo-classical style to incorporate Korean tradition with new technology. It was awarded 1st place of 2nd Korean Architecture Award in October 1993, the year it was completed.[19] Right pillar of the main gate is engraved as Korean: 헌법재판소 meaning the Constitutional Court itself, while the left pillar gate is engraved as Korean: 헌법재판소사무처 meaning the Department of Court Administration. It includes the courtroom, office and deliberation chamber for Justices, office for Rapporteur Judges, Academic Advisors and Constitutional Researchers, and one of working space for Department of Court Administration. The Annex building, built in April 2020 as three-story building tried to enhance communication with public and barrier-free accessibility. It includes law library, permanent exhibition hall for visitors and another working space for the department.[20] The Court usually holds open hearing session or session for verdict in 2nd and last Thursday of a month, and visitors with ID cards or passports may attend the session. However, unaccompanied tour on building is restricted for security of the Court.[21]

Procedure

As South Korea has predominant civil law tradition, major sequence of review procedure in the Constitutional Court of Korea stipulated in Chapter 3 of Constitutional Court Act is structured into two phases. First phase is investigating preliminary conditions on admissibility of case, not on merits. For example, if the plaintiff (who made request for adjudication) lapsed deadline for request, the case is formally decided as 'Dismissed' (Korean: 각하) no matter how much the plaintiff's request is right or not. This phase is named as 'Prior review' (Korean: 사전심사) under article 72 of the Act. Second phase is reviewing and deliberating merits of case. This phase is mainly fulfilled without oral hearing, yet the Court may hold oral hearing session if necessary, according to article 30 of the Act. If a case had passed prior review phase yet could not prove merits, the cas is formally decided as 'Rejected' (Korean: 기각). Otherwise, it is decided as 'Upheld' yet the specific form of upheld decision varies with each of jurisdiction, especially in judicial review of statutes.

First phase, the 'Prior review' is delivered by three different Panel (Korean: 지정재판부) of the Court, and each of the Panel is composed of three Justices. At this phase, the Court takes inquisitorial system to investigate every possible omit of preliminary conditions. If the Panel decides unanimously that the case lacks any of preliminary conditions, the case is dismissed. Otherwise, the case goes to second phase, where the Full bench (Korean: 전원재판부) composed of all possible Justices with the President of the Court as presiding member, reviews the case by article 22 of the Act. Though the case may already passed Prior review, still it can be dismissed since other Justices who did not participated in Prior review of such case can have different opinion.

Votes and Quorum of Full Bench

According to 113(1) of the Constitution and article 23(2) of the Act, to make decision upholding requests for the Adjudication, or to change precedent, the Court needs votes from at least six Justices among quorum of at least seven Justices. The only exception is making uphold decision in Adjudication on competence dispute. It only requires simple majority to make uphold decision. Otherwise, for example, to dismiss or to reject case, only simple majority with quorum of at least seven Justices is need to make decision. If there's no simple majority opinion, the opinion of the Court is decided by counting votes from the most favorable opinion for the plaintiff to the most unfavorable opinion for the plaintiff, until the number of votes gets over six. When the counted votes are over six, the most unfavorable opinion inside the votes over six are regarded as opinion of the Court.

Presiding Justice and Justice in charge

In South Korea, among panel of Judges or Justices, there should be 'presiding member (Korean: 재판장)' and 'member in charge (Korean: 주심)'. The presiding member is official representative of the panel. The member in charge is who oversees hearing and trial and writes draft judgment for each specific case. This role of 'member in charge' is mostly similar to Judge-Rapporteur in European Court of Justice. Usually the member in charge is automatically (or randomly) selected by computer to negate suspicion of partiality. However, the presiding member is bureaucratically selected by seniority. Due to this virtual difference in role, 'presiding Judge' in South Korean courts usually refer toKorean: 부장판사 which means such Judge is bureaucratically regarded as 'head of the panel', not who really takes role of presiding member in each of specific cases. For example, former Justice Kang Il-won was 'Justice in charge' (Korean: 주심재판관) in Impeachment of Park Geun-hye case, so he presided much of hearings, though official presiding member of the Full bench at that time was former Justice Lee Jung-mi as acting President of the Court.[22]

Case naming

Cases in the Constitutional Court are named as following rule. First two or four digit Arabic numbers indicate the year when the case is filed. And the following case code composed of Alphabets are categorized into eight; Hun-Ka, Na, Da, Ra, Ma, Ba, Sa and A. Each of the code matches with specific jurisdiction of the Court. The last serial number is given in the order of case filing of each year.[23]

Jurisdiction

The Constitutional Court's jurisdiction is set out in Article 111(1) of South Korea's Constitution as follows: adjudication on (1) constitutionality of statutes, (2) impeachment, (3) dissolution of a political party, (4) competence dispute, and (5) constitutional complaint.[24] While the South Korean Constitutional Court's organizational structure was influenced by Austria, the scope of its jurisdiction was modeled after Germany.

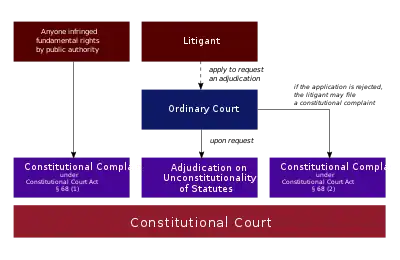

Judicial review of statutes

According to Article 111(1), 1. of the Constitution, the Constitutional Court may review the constitutionality of statutes at the request of ordinary courts—a power referred to as judicial review (Korean: 사법심사) or officially Adjudication on the constitutionality of statutes (Korean: 위헌법률심판) in Chapter 4, Section 1 of the Constitutional Court Act. In a legal dispute, if the court's decision depends on the constitutionality of laws relevant to the case, either party may request the court to refer the matter to the Constitutional Court for review. However, the court has discretion on whether to follow through with such a referral. If the court decides not to refer the matter, the aggrieved party can file a "constitutional complaint" directly with the Constitutional Court. The procedural hurdles involved in requesting adjudication on the constitutionality of statutes imply that only parties directly involved in an ongoing legal case are eligible to request a referral from the court. This means that abstract or potential injuries are not eligible for this legal resource. In other words, a party must have a concrete and specific interest in the outcome of the case to request a referral to the Constitutional Court.

Article 41(5) of the Constitutional Court Act establishes that once an ordinary court has requested the Constitutional Court to adjudicate on the constitutionality of statutes, no superior court, including the Supreme Court of Korea, may intervene. This restriction on the powers of the Supreme Court was motivated by its historical passivity in confronting other branches of government during periods of authoritarian rule.

However, this clause was abused by President Park Chung Hee under the Yushin Constitution. He refused to re-appoint Supreme Court justices who challenged his authority, effectively preventing the ordinary courts from making any formal requests for constitutional review. This event laid bare the vulnerabilities of making constitutional review contingent upon a court's request.

As a result, the 1987 tenth constitutional amendment introduced another avenue for an interested party to bypass the court and directly ask the Constitutional Court to intervene in constitutional review. This alternative route, called Constitutional Complaint (Korean: 헌법소원심판), is defined in Article 68(2) of the Constitutional Court Act.[25]

| Decision | Description |

|---|---|

| Unconstitutional (Korean: 위헌) | When the Constitutional Court declares a statute unconstitutional, the relevant law is nullified, and the decision takes effect immediately. In the case of criminal laws, the decision applies retroactively, unless a previous Constitutional Court decision upheld the same statute. In such instances, the decision is retroactively applied until the time of the previous relevant decision. This means that those who were previously convicted under the unconstitutional statute may have their convictions overturned or may be eligible for retrial. |

| Constitutional (Korean: 합헌) | When the Constitutional Court declares a statute constitutional, the relevant law remains in effect. This means that the statute remains valid and enforceable, and the decision does not affect any ongoing or past legal proceedings related to the law. |

| Unconformable (Korean: 헌법불합치) | When a statute is declared unconformable to the Constitution, the law is deemed unconstitutional in essence but remains in effect until the National Assembly amends the law. In such decisions, the Constitutional Court sets a deadline after which the relevant law expires and becomes unenforceable. The National Assembly is responsible for amending the law to ensure that it conforms to the Constitution, and failure to do so within the specified deadline can result in legal consequences. |

| Conditionally Unconstitutional (Korean: 한정위헌), Conditionally Constitutional (Korean: 한정합헌) | When a statute is declared conditionally constitutional by the Constitutional Court, it means that the law must be interpreted in a certain way to ensure that it is constitutional. Alternatively, the Court may also declare a statute conditionally unconstitutional, meaning that the law is unconstitutional if interpreted in a certain way. These types of decisions are known as "derivative decisions" (Korean: 변형결정) and are often a point of contention between the Constitutional Court and the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court has argued that such derivative decisions encroach upon the court's traditional role of interpreting statutes and could lead to confusion and inconsistency in the application of the law. On the other hand, the Constitutional Court has justified its use of derivative decisions by stating that they are necessary to ensure that the law conforms to the Constitution while respecting the legislative intent and separation of powers. |

Impeachment

Impeachment adjudication (Korean: 탄핵심판) is another prominent power of the Constitutional Court. According to Article 65(1) of the Constitution, if the President, Prime Minister, or other state council members violate the Constitution or other laws of official duty, the National Assembly can file an impeachment motion with at least one third of the members of the National Assembly. In order to pass, the motion must receive the support of a supermajority if it concerns the President, and a simple majority for any other office. Once the impeachment motion passes the National Assembly, the Constitutional Court adjudicates the impeachment, and until the Constitutional Court reaches a decision, the person against whom the impeachment motion was lodged is suspended from exercising his or her power.

Neither the Constitution nor the Constitutional Court Act lays out concrete criteria to be considered in an impeachment case. Therefore, the Constitutional Court's decisions play an important role in establishing standards of review for impeachment cases. There have been two presidential impeachment cases: the failed impeachment of Roh Moo-hyun of 2004 and the successful impeachment of Park Geun-hye of 2017. In the ruling on the impeachment of President Roh Moo-hyun, the Court declared that a 'grave (Korean: 중대한)' violation of the law is required for the impeachment of a President. However, in the impeachment case of President Park Geun-hye, the Constitutional Court held that a violation of the Constitution is sufficient cause for impeachment, even if there is no grave violation of the law or statutes.[26]

Dissolution of political parties

Under the Constitution of South Korea, the government has the right to request the dissolution of a political party if its objectives or activities are deemed to be in opposition to the principles of the liberal democratic basic order (German: Freiheitliche demokratische Grundordnung; Korean: 민주적 기본질서), and such requests are adjudicated by the Constitutional Court. The party-dissolution provision was influenced by its German equivalent, called 'Party Ban' (German: Parteiverbot), designed to prevent the recurrence of events like the rise of the Nazis.[27] While the clear provision for dissolving a political party serves to prevent anti-democratic factions from destabilizing society, it also acts as a safeguard against attempts to dissolve a party as a means of suppressing dissent and stifling free expression since a dictator cannot dissolve at will a political party challenging his or her authority.

The Constitutional Court rarely accepts dissolution petitions, and even less often rules in favor of dissolving a political party. As of April 2023, the Unified Progressive Party (UPP, Korean: 통합진보당) is the only political party dissolved through the party-dissolution provision.[28][29][30]

Competence disputes

The Constitution of South Korea empowers the Constitutional Court to adjudicate competence disputes (Korean: 권한쟁의심판), which is derived from the German 'Organs Dispute' (German: Organstreit).[31] Competence is legal jargon defined as the "legal authority to deal with a particular matter," and therefore, competence disputes are legal cases between state agencies (Korean: 국가기관) or local governments (Korean: 지방자치단체) asking the Constitutional Court to adjudicate which party does or does not have "competence." In some instances, two separate agencies may have overlapping powers, which are defined in the relevant statutes that grant those powers. As a result, it may become necessary to distinctly establish the agency responsible for a particular matter. In some other cases, the existence of competence itself can be disputed. For example, the central government in Seoul may delegate certain government projects to local governments, which uses the labor and resources of the local government. Local governments may lodge a competence-dispute lawsuit with the Constitutional Court to challenge the constitutionality of the delegation, citing their lack of constitutional competence to undertake the delegated tasks.

Constitutional complaints

According to article 111(1), 5. of the Constitution and article 68(1) of Constitutional Court Act, the Court may review whether basic right of the plaintiff is infringed by any public authorities. Influenced by German institution called Verfassungsbeschwerde, this Adjudication on Constitutional complaint (Korean: 헌법소원심판) system is designed as last resort for defending basic rights under the Constitution. Thus basically, the Court can adjudicate the complaint only if when other possible remedies are exhausted. Yet the Adjudication on Constitutional complaint is not accompanied with lawsuits on civil liability, since judgment on civil liability is role of ordinary courts. The Court only reviews whether the basic right of the plaintiff is infringed or not in this adjudication process. Detailed issues on calculation of damage and compensation is out of the Court's jurisdiction. This type of adjudications are usually dismissed in Prior review due to lack of preliminary conditions.

In addition, there's another unique type of constitutional complaint under article 68(2) of the Act, as discussed above in paragraph of 'on Constitutionality of statutes'. This constitutional complaint by article 68(2) of the Act is detour for Adjudication on the constitutionality of statutes (or judicial review) denied by ordinary courts. It is usually called as 'Korean: 법령소원심판' in Korean, which means constitutional complaint especially on statutes. As this type of constitutional complaint is designed as detour for judicial review, the preliminary conditions required in Prior review for constitutional complaint under article 68(2) is different from the complaints under article 68(1) of the Act. It does not require any possible remedies to be exhausted already, but requires the plaintiff was dismissed of claim for judicial review from the ordinary court about on-going case of the plaintiff. It is notifiable that on-going case is not automatically sustained during Adjudication on Constitutional complaint by article 68(2) of the Act.

Statistics

Below are the aggregated statistics as of 09 Feb 2021.[32]

| Type | Total | Constitutionality of statutes |

Impeachment | Dissolution of a political party |

Competence dispute |

Constitutional complaint | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub total | §68 I | §68 II | |||||||

| Filed | 41,615 | 1,008 | 2 | 2 | 115 | 40,488 | 32,074 | 8,414 | |

| Settled | 40,303 | 957 | 2 | 2 | 110 | 39,232 | 31,264 | 7,968 | |

| Dismissed by panel | 24,476 | 24,476 | 19,915 | 4,561 | |||||

| Decided by full bench |

Unconstitutional | 655 | 294 | 361 | 113 | 248 | |||

| Nonconformity | 262 | 82 | 180 | 75 | 105 | ||||

| Conditionally unconstitutional |

70 | 18 | 52 | 20 | 32 | ||||

| Conditionally constitutional |

28 | 7 | 21 | 21 | |||||

| Constitutional | 2,843 | 359 | 2,484 | 4 | 2,480 | ||||

| Upholding | 794 | 1 | 1 | 19 | 773 | 773 | |||

| Rejected | 7,998 | 1 | 27 | 7,970 | 7,970 | ||||

| Dismissed | 2,115 | 73 | 1 | 45 | 1,996 | 1,611 | 385 | ||

| Other | 10 | 10 | 8 | 2 | |||||

| Withdrawn | 1,052 | 124 | 19 | 909 | 775 | 134 | |||

| Pending | 1,312 | 51 | 5 | 1,256 | 810 | 446 | |||

International relations

- Venice Commission : As the Republic of Korea is a member state of the Venice Commission, one of associate Justices in Constitutional Court of Korea becomes member for the commission. Substitute members are conventionally designated in following two positions; Deputy Secretary General at the Court's Department of Court Administration, and Deputy Minister of Ministry of Justice. Current member is Justice Lee Suk-Tae.[33]

- Association of Asian Constitutional Courts and Equivalent Institutions : The Republic of Korea is founding member state of the Association of Asian Constitutional Courts & Equivalent Institutions (AACC), and seat for permanent secretariat of the AACC. President of the Constitutional Court of Korea attends the Board of AACC as representing the Republic of Korea.

Criticism and Issues

According to Article 113(1) of the Constitution, the Constitutional Court is required to have at least six justices present in order to issue a ruling, but there is no contingency plan for in case the quorum is not met.[34] Articles 6(4) and (5) of the Constitutional Court Act simply require that the vacancy be filled within 30 days, without any meaningful backup plan for when the deadline is not met, which exposes the Constitutional Court to potential political instability or gridlock, particularly between the President and the National Assembly. Although the Supreme Court of Korea similarly lacks contingency measures to address a potential vacancy, there is a key difference since the Constitutional Court needs a supermajority to issue a ruling, but the Supreme Court needs only a simple majority.

Relationship with Supreme Court

The relationship between the Constitutional Court of Korea and the Supreme Court of Korea is a hotly-debated topic among Korean jurists.[35][36][37][38] The Constitution does not establish a clear hierarchy between the two highest courts, and the ranks of the respective chief justices are equal under the Constitutional Court Act. Since the co-equal relationship of the courts relies on a piece of legislation, the National Assembly could pass an amendment and rank the heads of the courts differently, which would resolve this issue. However, as it stands, there is no remedy if the two highest courts disagree on a constitutional case.

There are several areas in which the two highest courts have come into conflict, most notably jurisdiction over executive orders, which include presidential decrees and ordinances, can fall on either court, depending on the interpretation. Article 107(2) of the Constitution states the Supreme Court shall preside over and have the final say in cases concerning the legality of executive orders. However, the Constitutional Court has held that a litigant may file a complaint directly with the Constitutional Court if the litigant believes his or her constitutional rights were infringed upon by an executive order. The Constitution also grants the Constitutional Court jurisdiction over complaints of constitutional violations as prescribed by an act of the National Assembly. In addition, the Constitutional Court Act gives the Constitutional Court the authority to review the constitutionality of all government actions. Since the Constitution itself empowers both courts to hear the same cases, this puts the two courts into endless strife.

The highest courts also fiercely disagree over the Constitutional Court's power to declare a law unconstitutional as applied (Korean: 한정위헌결정), which means the statute itself is constitutional but as it is applied by either the executive branch or inferior courts does run afoul of the Constitution. The Supreme Court of Korea does not recognize the binding power of such "unconstitutional as applied" decisions by the Constitutional Court, as the Supreme Court interprets such decisions as essentially upholding the statutes in dispute. That indicates that the Supreme Court may ignore such decisions and proceed as it sees fit, which has happened several times. The Constitutional Court may counter that by suspending state powers that may violate the Constitution, which the Constitutional Court interprets to include the Supreme Court's decision to hear a case. The Constitutional Court suspended Supreme Court trials once in 1997 and twice in 2022, which has brought the nation on the verge of a constitutional crisis.

As both courts claim sharply divergent, there are conflicting interpretations of their powers, and the Constitution does not expressly state the court that has the final say, there is no way to resolve such conflicts within the current system.

Gallery

.svg.png.webp) Emblem of the Constitutional Court of Korea (1988–2017)

Emblem of the Constitutional Court of Korea (1988–2017).svg.png.webp) Flag of the Constitutional Court of Korea (1988–2017)

Flag of the Constitutional Court of Korea (1988–2017) Flag of the Constitutional Court of Korea (from 2017)

Flag of the Constitutional Court of Korea (from 2017)

See also

- Constitution of South Korea

- Politics of South Korea

- Government of South Korea

- Judiciary of South Korea

- President of the Constitutional Court of Korea

- List of justices of the Constitutional Court of Korea

- Rapporteur Judge

- Supreme Court of Korea

- Venice Commission

- Association of Asian Constitutional Courts and Equivalent Institutions

References

- "CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF KOREA | 국가법령정보센터 | 영문법령 > 본문". www.law.go.kr. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- "대한민국 영문법령". elaw.klri.re.kr. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- "History of Constitutional Adjudication". Constitutional Court of Korea. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- "Constitutional Court of Korea > Constitutional Court of Korea > About the Court > History".

- "KIM, MARIE SEONG-HAK. "Travails of Judges: Courts and Constitutional Authoritarianism in South Korea." The American Journal of Comparative Law, vol. 63, no. 3, 2015, pp. 612-614, 641". JSTOR 26425431. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- "Garoupa, Nuno, and Tom Ginsburg. "Building Reputation in Constitutional Courts: Political and Judicial Audiences." Arizona Journal of International and Comparative Law, vol. 28, no. 3, Fall 2011, p. 563". Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- For major decisions of the Constitutional Court of Korea, see "Major Decisions in Brief". Constitutional Court of Korea. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- "West, James M., and Dae-Kyu Yoon. "The Constitutional Court of the Republic of Korea: Transforming the Jurisprudence of the Vortex?" The American Journal of Comparative Law, vol. 40, no. 1, 1992, pp. 76-77". JSTOR 840686. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- "The Supreme Court of Justice". Oberster Gerichtshof English Website. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- "Constitution of the Republic of Korea". Korea Legislation Research Institute. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- "Constitutional Court Act". Korea Legislation Research Institute. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- For example, see "Page 127 of 16-2(B) KCCR 1, 2004Hun-Ma554, 566(consolidated), October 21, 2004". Constitutional Court of Korea. Retrieved 2022-04-05. for the Constitutional Court and "Supreme Court Decision 2020Do12017 Decided August 26, 2021" (in Korean). Supreme Court of Korea. Retrieved 2022-04-05. for the Supreme Court

- "Moon likely to ask for confirmation hearing report on embattled justice minister nominee". Yonhap News Agency. 2019-09-01. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- The two Constitutional Court Justices who renewed their term is Justice Kim Chin-woo and Kim Moon-hee, both affected by President Kim Young-sam "Former Justices". Constitutional Court of Korea. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- "les magistrats du siege" (in French). Cour de Cassation. Retrieved 2022-04-10.

- "Gerichtsschreiber und Gerichtsschreiberinnen" (in German). Bundesgericht. Retrieved 2022-04-10.

- "Sanders, A. (2020). Judicial Assistants in Europe – A Comparative Analysis. International Journal for Court Administration, 11(3), 2". doi:10.36745/ijca.360. S2CID 229516417. Retrieved 2022-04-10.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Constitutional Research Institute, Official Website". Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- "1993, 한국건축문화대상" (in Korean). Architecture & Urban Research Institute. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- "Building". Constitutional Court of Korea. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- "Open Hearings". Constitutional Court of Korea. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- "Impeachment deliberation kicks off". Yonhap News Agency. 2017-03-01. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- "Case number, Search Guide for Decisions". Constitutional Court of Korea. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- For more detailed introduction of the jurisdiction, see "Types of Jurisdiction". Constitutional Court of Korea. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- While rare, a number of cases in South Korea have emerged where the ordinary courts refused to refer matters to the Constitutional Court for constitutional review. In some of these cases, the statutes in question were eventually struck down after being petitioned directly through constitutional complaint. This indicates that the ordinary courts in South Korea remain hesitant to make referrals for constitutional review, even after the country's transition to democracy in 1987. Though infrequent, such cases underscore the significance of constitutional complaints in allowing individuals or groups to directly challenge the constitutionality of laws without the need for a referral from the ordinary courts. See "Yoon, Dae-Kyu. "The Constitutional Court System of Korea: The New Road for Constitutional Adjudication" Journal of Korean Law, vol. 1, no. 2, 2011, pp. 10-11". Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- "2004Hun-Na1, Major Decisions in Brief". Constitutional Court of Korea. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- "Proceedings for the prohibition of political parties". Federal Constitutional Court. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- "South Korea: Unprecedented Claim Filed with Constitutional Court to Dissolve a Political Party". Library of Congress, United States. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- "2013Hun-Da1, Major Decisions in Brief". Constitutional Court of Korea. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- "South Korea's Political Divisions on Display With Lee Seok-ki Case". The Diplomat. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- "Organstreit proceedings". Federal Constitutional Court. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- "Constitutional Court Korea > > Jurisdiction > Statistics". Constitutional Court of Korea. Retrieved 2021-02-09.

- "Korea, Republic, Member states". Venice Commission. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- Other countries have implemented various contingency systems to prevent the highest court from being paralyzed. For instance, Austrian constitutional court prepares a 'substitute member' in advance to fill an abrupt vacancy. Also, Germany's constitutional court sustains current member's term until the successor is appointed by Section 3, Clause 4 of the Act on the German Federal Constitutional Court (German: Bundesverfassungsgerichtsgesetz). See "Act on the Federal Constitutional Court". Gesetze-im-Internet. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- Kim, Hyunchul (30 September 2020). "A Study on the Reform of the Judiciary Structure — Focussing on the Conflict between the Constitutional Court and the Supreme Court —". Yonsei Law Review. 30 (3): 259–307. doi:10.21717/ylr.30.3.9. S2CID 226360239. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- Hyeon, Nam Bok (2021). "Loesungen der Konflikten zwischen KVerfG und KGG in Sued-Korea". Constitutional Law (in Kanuri). pp. 495–536. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- 최, 완주 (2006). "Reform der koreanischen Verfassungsgerichtsbarkeit". Korean Lawyers Association Journal (in Kanuri). pp. 19–60. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- Kim, Dai-Whan (2012). "Die Beziehungen zwischen Gerichte und Verfassungsgericht aus dem Standpunkt der Überprüfungsgegenstände der Verfassungsmäßigkeit". Public Law (in Kanuri). pp. 1–27. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

External links

- the Constitutional Court of Korea Official Website

- The Constitution of the Republic of Korea (translated into English), Korea Legislation Research Institute

- Constitutional Court Act (translated into English), Korea Legislation Research Institute

- Thirty Years of the Constitutional Court of Korea (1988-2018), published and downloadable by the Constitutional Court of Korea