Atomic spies

Atomic spies or atom spies were people in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada who are known to have illicitly given information about nuclear weapons production or design to the Soviet Union during World War II and the early Cold War. Exactly what was given, and whether everyone on the list gave it, are still matters of some scholarly dispute. In some cases, some of the arrested suspects or government witnesses had given strong testimonies or confessions which they recanted later or said were fabricated. Their work constitutes the most publicly well-known and well-documented case of nuclear espionage in the history of nuclear weapons. At the same time, numerous nuclear scientists wanted to share the information with the world scientific community, but this proposal was firmly quashed by the United States government. It is worth noting that many scientists who worked on the Manhattan Project were deeply conflicted about the ethical implications of their work, and some were actively opposed to the use of nuclear weapons.

Atomic spies were motivated by a range of factors. Some, such as ideology or a belief in communism, were committed to advancing the interests of the Soviet Union. Others were motivated by financial gain, while some may have been coerced or blackmailed into spying. The prospect of playing a role in shaping the outcome of the Cold War may also have been appealing to some. Another large motivational factor was to be engrained into the history of the world, and to be remembered as someone who did something larger than themselves. Regardless of their specific motivations, each individual played a major role in the way the Cold War unfurled and the current state of nuclear weapons.

Confirmation about espionage work came from the Venona project, which intercepted and decrypted Soviet intelligence reports sent during and after World War II. In 1995, the U.S. declassified its Venona Files which consisted of deciphered 1949 Soviet intelligence communications.[1] These provided clues to the identity of several spies at Los Alamos and elsewhere, some of whom have never been identified. These decrypts prompted the arrest of naturalized British citizen Klaus Fuchs in 1950.[2] Fuchs’ confession led to the discovery of spy Harry Gold who served as his Soviet courier.[3] Gold identified spy David Greenglass, a Los Alamos Army-machinist. Greenglass identified his brother-in-law, spy Julius Rosenberg, as his control.[2] The Venona Files corroborated their espionage activities and also revealed others in the network of Soviet spies, including physicist Theodore Hall who also worked at Los Alamos.[4] Some of this information was available to the government during the 1950s trials, but it was not usable in court as it was highly classified. Additionally, historians have found that records from Soviet archives, which were briefly opened to researchers after the fall of the Soviet Union, included more information about some spies.

Transcription of declassified Soviet KGB documents by ex-KGB officer Alexander Vassiliev provides additional details about Soviet espionage from 1930 to 1950, including the greater extent of Fuchs, Hall, and Greenglass's contributions.[4] In 2007, spy George Koval, who worked at both Oak Ridge and Los Alamos, was revealed.[5] According to Vassiliev's notebooks, Fuchs provided the Soviet Union the first information on electromagnetic separation of uranium and the primary explosion needed to start the chain reaction, as well as a complete and detailed technical report with the specifications for both fission bombs.[4] Hall provided a report on Los Alamos principle bomb designs and manufacturing, the plutonium implosion model, and identified other scientists working on the bomb.[4] Greenglass supplied information on the preparation of the uranium bomb, calculations pertaining to structural issues with it, and material on producing uranium-235.[4] Fuchs’ information corroborated Hall and Greenglass.[6][4] Koval had access to critical information on dealing with the reactor-produced plutonium's fizzle problem, and how using manufactured polonium corrected the problem.[5] With all the stolen information, Soviet nuclear ability was advanced by several years at least.[2]

Importance

Before World War II, the theoretical possibility of nuclear fission resulted in intense discussion among leading physicists world-wide. Scientists from the Soviet Union were later recognized for their contributions to the understanding of a nuclear reality and won several Nobel Prizes. Soviet scientists such as Igor Kurchatov, L. D. Landau, and Kirill Sinelnikov helped establish the idea of, and prove the existence of, a splittable atom. Dwarfed by the Manhattan Project conducted by the US during the war, the significance of the Soviet contributions has been rarely understood or credited outside the field of physics. According to several sources, it was understood on a theoretical level that the atom provided for extremely powerful and novel releases of energy and could possibly be used in the future for military purposes.[7]

In recorded comments, physicists lamented their inability to achieve any kind of practical application from the discoveries. They thought that creation of an atomic weapon was unattainable. According to a United States Congressional joint committee, although the scientists could conceivably have been first to generate a man-made fission reaction, they lacked the ambition, funding, engineering capability, leadership, and ultimately, the capability to do so. The undertaking would be of an unimaginable scale, and the resources required to engineer for such use as a nuclear bomb, and nuclear power were deemed too great to pursue.[8]

At the urging of Albert Einstein and Leo Szilard in their letter of August 2, 1939, the United States — in collaboration with Britain and Canada — recognized the potential significance of an atomic bomb. They embarked in 1942 upon work to achieve a usable device. Estimates suggest that during the quest to create the atomic bomb, an investment of $2 billion, temporary use of 13,000 tons of silver, and 24,000 skilled workers drove the research and development phase of the project.[9] Those skilled workers included the people to maintain and operate the machinery necessary for research. The largest Western facility had five hundred scientists working on the project, as well as a team of fifty to derive the equations for the cascade of neutrons required to drive the reaction. The fledgling equivalent Soviet program was quite different: The program consisted of fifty scientists, and two mathematicians trying to work out the equations for the particle cascade.[10] The research and development of techniques to produce sufficiently enriched uranium and plutonium were beyond the scope and efforts of the Soviet group. The knowledge of techniques and strategies that the Allied programs employed, and which Soviet espionage obtained, may have played a role in the rapid development of the Soviet bomb after the war.

The research and development of methods suitable for doping and separating the highly reactive isotopes needed to create the payload for a nuclear warhead took years and consumed a vast quantity of resources. The United States and Great Britain dedicated their best scientists to this cause and constructed three plants, each with a different isotope-extraction method.[11] The Allied program decided to use gas-phase extraction to obtain the pure uranium necessary for an atomic detonation.[8] Using this method took large quantities of uranium ore and other rare materials, such as graphite, to successfully purify the U-235 isotope. The quantities required for the development were beyond the scope and purview of the Soviet program.

The Soviet Union did not have natural uranium-ore mines at the start of the nuclear arms race but in early 1943 it began to acquire uranium metal, uranium oxide, and uranium nitrate through the Lend-Lease Agreement with the U.S.[12] By February 1943, Laboratory No. 2 was established by decree of the Soviet Academy of Sciences, with Igor V. Kurchatov as its head. Kurchatov recruited Khariton to work with him.[13] A lack of materials made it very difficult for them to conduct novel research or to map out a clear pathway to achieving the fuel they needed. The Soviet scientists became frustrated with the difficulties of producing uranium fuel cheaply, and they found their industrial techniques for refinement lacking. The use of information stolen from the Manhattan Project eventually rectified the problem.[14] Without such information, the problems of the Soviet atomic team would have taken many years to correct, affecting the production of a Soviet atomic weapon significantly.

Some historians believe that the Soviet Union achieved its great leaps in its atomic program by the espionage information and technical data that Moscow succeeded in obtaining from the Manhattan Project. Once the Soviets had learned of the American plans to develop an atomic bomb during the 1940s, Moscow began recruiting agents to get information.[15] Moscow sought very specific information from its intelligence cells in America and demanded updates on the progress of the Allied project. Moscow was also greatly concerned with the procedures being used for U-235 separation, what method of detonation was being used, and what industrial equipment was being used for these techniques.[16]

The Soviet Union needed spies who had security clearance high enough to have access to classified information at the Manhattan Project and who could understand and interpret what they were stealing. Moscow also needed reliable spies who believed in the communist cause and would provide accurate information. Theodore Hall was a spy who had worked on the development of the plutonium bomb the US dropped in Japan.[17] Hall provided the specifications of the bomb dropped on Nagasaki. This information allowed the Soviet scientists a first-hand look at the setup of a successful atomic weapon built by the Manhattan Project.

The most influential of the atomic spies was Klaus Fuchs. Fuchs, a German-born British physicist, went to the United States to work on the atomic project and became one of its lead scientists. Fuchs had become a member of the Communist Party in 1932 while still a student in Germany. At the onset of the Third Reich in 1933, Fuchs fled to Great Britain. He eventually became one of the lead nuclear physicists in the British program. In 1943 he moved to the United States to collaborate on the Manhattan Project.[18] Due to Fuchs's position in the atomic program, he had access to most, if not all, of the material Moscow desired. Fuchs was also able to interpret and understand the information he was stealing, which made him an invaluable resource. Fuchs provided the Soviets with detailed information on the gas-phase separation process. He also provided specifications for the payload, calculations and relationships for setting of the fission reaction, and schematics for labs producing weapons-grade isotopes.[19] He reported on the existence of America's plutonium bomb plans including its plutonium production plant at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Fuchs revealed that a plutonium bomb needed an implosion method of detonation rather than the gun method utilized in a uranium bomb. Ultimately, he provided the design of the plutonium bomb that was used for the Trinity test, a description of its initiator, that it had solid not hollow plutonium core, and other details about its design specification, the size of the explosion it would generate, and when and where it would be tested.[4] This information helped the smaller under-manned and under-supplied Soviet group move toward the successful detonation of a nuclear weapon. Fuchs also had a significant role in advancing Soviet production of the fusion hydrogen bomb.[20] He had attended Los Alamos’ meetings in 1946 on “Super” and worked on its dual implosion/ignition reaction, information about which he shared with Moscow through 1948.[13] His contributions are reflected in the fact that within a year of the first U.S. hydrogen bomb test in 1952, the USSR successfully tested its hydrogen bomb in 1953.

Another extremely important individual that played a significant role in the Soviet Union's acquisition of atomic secrets was Harry Gold. He acted as a soviet spy during the 1940s and early 1950s, aiding the exchange of American nuclear program information to the Soviets.[21] Gold's primary contact in the Soviet intelligence agency was a man named Anatoli Yatskov. Yakovlev was stationed at the Soviet consulate in New York City and tasked with recruiting American citizens to spy on behalf of the Soviet Union. Yakovlev recruited a number of people to work for the Soviet Union, including Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, David Greenglass, and Klaus Fuchs. Gold's role in this network was to act as a courier, passing along information and money between the Soviet agents in the United States and their handlers in Moscow. He also helped to recruit new spies and served as a translator for some of the intelligence materials that were passed along. Without atomic spies such as Harry Gold, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, David Greenglass, and Klaus Fuchs the rate in which the Soviet Union achieved nuclear weaponry would have been impossible. Gold's work as a spy came to an end in 1950 when he was arrested by the FBI.[22] He was eventually convicted of espionage and sentenced to 30 years in prison. However, he was released after serving only 15 years as part of a prisoner exchange program with the Soviet Union.

The Soviet nuclear program would have eventually been able to develop a nuclear weapon without the aid of espionage. It did not develop a basic understanding of the usefulness of an atomic weapon, the sheer resources required, and the talent until much later. Espionage helped the Soviet scientists identify which methods worked and prevented their wasting valuable resources on techniques which the development of the American bomb had proven ineffective. The speed at which the Soviet nuclear program achieved a working bomb, with so few resources, depended on the amount of information acquired through espionage. During the Cold War trials, the United States emphasized the significance of that espionage.[23]

Notable spies

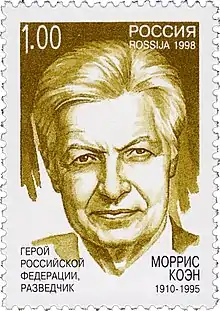

- Morris Cohen — an American, "Thanks to Cohen, designers of the Soviet atomic bomb got piles of technical documentation straight from the secret laboratory in Los Alamos," the newspaper Komsomolskaya Pravda said. Morris and his wife, Lona, served eight years in prison, less than half of their sentences, before being released in a prisoner swap with the Soviet Union. He died without revealing the name of the American scientist who helped pass vital information about the United States atomic bomb project.[24]

- Klaus Fuchs — the German-born British theoretical physicist who worked with the British delegation at Los Alamos during the Manhattan Project. Fuchs was arrested in the UK and tried there. Lord Goddard sentenced him to fourteen years' imprisonment, the maximum for violating the Official Secrets Act. Fuchs escaped the charge of espionage due to a lack of independent evidence and because, at the time of his activities, the Soviet Union was an ally, not an enemy, of Great Britain.[21] In December 1950 he was stripped of his British citizenship. He was released on June 23, 1959, after serving nine years and four months of his sentence at Wakefield prison. Fuchs was allowed to emigrate to Dresden, then in communist East Germany.[25][26] In his 2019 book, Trinity: The Treachery and Pursuit of the Most Dangerous Spy in History, Frank Close asserts that "it was primarily Fuchs who enabled the Soviets to catch up with Americans" in the race for the nuclear bomb.[27]

- Harry Gold — an American, confessed to acting as a courier for Greenglass and Fuchs. In 1951, Gold was sentenced to thirty years imprisonment. He was paroled in May 1966, after serving just over half of his sentence. Gold then returned to Philadelphia, where he worked as a chemist at a hospital.[28]

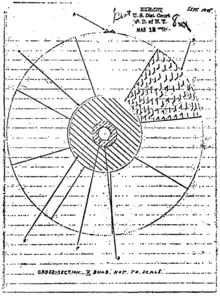

- David Greenglass — an American machinist at Los Alamos during the Manhattan Project. Greenglass confessed that he gave crude schematics of lab experiments to the Russians during World War II. He recanted some aspects of his testimony against his sister Ethel and brother-in-law Julius Rosenberg, which he said he gave in an effort to protect his own wife, Ruth, from prosecution. Greenglass was sentenced to 15 years in prison, served 10 years, and later reunited with his wife.[29]

- Theodore Hall — an American, was the youngest physicist at Los Alamos. He gave a detailed description of the Fat Man plutonium bomb, and of several processes for purifying plutonium, to Soviet intelligence. Afterward he moved to England. His identity as a spy was not revealed until very late in the 20th century. He was never tried for his espionage work, though he admitted to it in later years to reporters and to his family.[30][31]

- George Koval — the American-born son of a Belarusian emigrant family who returned to the Soviet Union. He was inducted into the Red Army and recruited into the Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU). He infiltrated the United States Army and became a radiation health officer in the Special Engineer Detachment. Acting under the code name Delmar he obtained information from Oak Ridge National Laboratory and the Dayton Project about the Urchin detonator used on the Fat Man plutonium bomb. His work was not known to the West until 2007, when he was posthumously recognized as a "Hero of the Russian Federation" by Vladimir Putin.[32][33][34]

- Irving Lerner — an American film director, he was caught photographing the cyclotron at the University of California, Berkeley in 1944.[35] After the war, he was blacklisted.

- Alan Nunn May — a British citizen, he was one of the first Soviet spies to be discovered. He worked on the Manhattan Project and was betrayed by a Soviet defector in Canada in 1946. He was convicted that year, which led the United States to restrict the sharing of atomic secrets with the UK. On May 1, 1946, he was convicted and sentenced to ten years hard labour. He was released in 1952, after serving 6½ years.[36]

- Julius and Ethel Rosenberg — Americans who were involved in coordinating and recruiting an espionage network that included Ethel's brother, David Greenglass, a machinist at Los Alamos National Lab. Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were tried for conspiracy to commit espionage. Treason charges were not applicable, since the United States and the Soviet Union were allies at the time. The Rosenbergs denied all the charges but were convicted in a trial in which the prosecutor Roy Cohn later said he was in daily secret contact with the judge, Irving Kaufman. Despite an international movement demanding clemency and appeals to President Dwight D. Eisenhower by leading European intellectuals and the Pope, both the Rosenbergs were executed in 1953, at the height of the Korean War. President Eisenhower wrote to his son, serving in Korea, that if he spared Ethel (presumably for the sake of her two young children), then the Soviets would recruit their spies from among women.[37][38][39]

- Saville Sax — an American, acted as the courier for Klaus Fuchs and Theodore Hall. Sax and Hall had been roommates at Harvard University.[30]

- Oscar Seborer — worked at Los Alamos from 1944 to 1946 and was part of a unit that studied the seismological effects of the Trinity nuclear test. Codenamed "Godsend" by the Soviets, he defected to the Soviet Union in 1951, and received the Order of the Red Star. He lived under the alias "Smith" and died in 2015. His identity was only revealed publicly in 2019.[40]

- Morton Sobell — an American engineer, he was tried and convicted of conspiracy, along with the Rosenbergs. He was sentenced to 30 years imprisonment on Alcatraz but released in 1969 on appeal and for good behavior after serving 17 years and 9 months.[41] In 2008, Sobell admitted to passing information to the Soviets, although he said it was all for defensive systems. He implicated Julius Rosenberg, in an interview with the New York Times published in September 2008.[42]

- Melita Norwood — British Communist, an active Russian spy from at least 1938 and never detected. Employed as a secretary in the British Non-Ferrous Metals Research Association since 1932, she was linked to the Woolwich Arsenal spy ring of 1938. In wartime she was seconded to "Tube Alloys", the secret British nuclear research project. She was later considered "the most important female agent ever recruited by the USSR". She was first suspected as a security risk in 1965 but never prosecuted. Her spying career was revealed by Vasili Mitrokhin in 1999, when she was still alive but long retired.

- Arthur Adams — Soviet spy who passed information about the Manhattan Project.[43]

Gallery

Lona Cohen on Russian stamp

Lona Cohen on Russian stamp Morris Cohen on Russian stamp

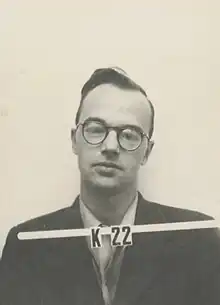

Morris Cohen on Russian stamp Klaus Fuchs ID badge photo from Los Alamos National Laboratory

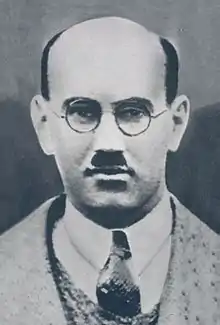

Klaus Fuchs ID badge photo from Los Alamos National Laboratory Mugshot of David Greenglass

Mugshot of David Greenglass Theodore Hall's ID badge photo from Los Alamos National Laboratory

Theodore Hall's ID badge photo from Los Alamos National Laboratory Alan Nunn May, University of Cambridge physicist

Alan Nunn May, University of Cambridge physicist Mugshot of Ethel Rosenberg

Mugshot of Ethel Rosenberg Police photograph of Julius Rosenberg after his arrest

Police photograph of Julius Rosenberg after his arrest Harry Gold after his arrest by the Federal Bureau of Investigation

Harry Gold after his arrest by the Federal Bureau of Investigation

References

- Earl., Haynes, John (2010). Spies : the rise and fall of the KGB in America. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-16438-1. OCLC 449855597.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - McKnight, David (2012-12-06). Espionage and the Roots of the Cold War. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203045589. ISBN 978-1-136-33812-0.

- Haynes, John Earl; Klehr, Harvey (2006). Early Cold War Spies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511607394. ISBN 978-0-511-60739-4.

- Earl., Haynes, John (2009). Spies : the rise and fall of the KGB in America. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12390-6. OCLC 778334787.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "George Koval: Atomic Spy Unmasked". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2022-04-16.

- Haynes, John Earl; Klehr, Harvey (2006), "Introduction: Early Cold War Spy Cases", Early Cold War Spies, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–22, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511607394.002, ISBN 9780521674072, retrieved 2022-04-16

- Schwartz, Michael. The Russian-A(merican) Bomb: The Role of Espionage in the Soviet Atomic Bomb Project. J. Undergrad. Sci. 3: 103–108 (Summer 1996) http://www.hcs.harvard.edu/~jus/0302/schwartz.pdf Archived 2019-10-29 at the Wayback Machine

- Joint Committee on Atomic Energy. Soviet Atomic Espionage. Chapters 2–3 United States Government Printing Office, Washington, 1951. https://archive.org/stream/sovietatomicespi1951unit#page/n3/mode/2up

- Schwartz, Michael. Russian Bomb 103–108

- Schwartz, Michael. Russian Bomb 103–108f

- Allen Weinstein and Alexander Vassiliev, "Atomic Espionage: from Fuchs to the Rosenburgs" in The Haunted Wood, (New York: Random House Inc, 1999), 172–222.

- DeGroot, Gerard J. (2004). The Bomb. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ Press. p. 131.

- De Groot, Gerard J. (2006). The bomb : a life. ISBN 0-674-02235-1. OCLC 1030101415.

- Weinstein and Vassiliev (1999), "Atomic Espionage," 180–85

- Weinstein and Vassiliev, "Atomic Espionage," pp. 190–200

- Weinstein and Vassiliev (1999), "Atomic Espionage," 180

- Holmes,Marian. "Spies Who Spilled Atomic Bomb Secrets". Smithsonian Magazine, 20 April 2009. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history-archaeology/Spies-Who-Spilled-Atomic-Bomb-Secrets.html

- Holmes, Spies Who Spilled, 1–2

- Weinstein and Vassiliev, "Atomic Espionage", 200–210

- Williams, Robert Chadwell. Klaus Fuchs, Atom Spy. ISBN 978-0-674-59389-3. OCLC 1154266475.

- A.M. Hornblum, The Invisible Harry Gold (Yale University Press, 2010) kindle edition. locations 4030–4037

- "Harry Gold". FBI. Retrieved 2023-04-29.

- Joint Committee Chapter 2

- "Morris Cohen, 84, Soviet Spy Who Passed Atom Plans in 40's". The New York Times. 5 July 1995. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

Morris Cohen, an American who spied for the Soviet Union and was instrumental in relaying atomic bomb secrets to the Kremlin in the 1940s, has died, Russian newspapers reported today. Mr. Cohen, best known in the West as Peter Kroger, died of heart failure in a Moscow hospital on June 23 at age 84, according to news reports.

- Pace, Eric (January 29, 1988). "Klaus Fuchs, Physicist Who Gave Atom Secrets to Soviet, Dies at 76". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

Klaus Fuchs, the German-born physicist who was imprisoned in the 1950s in Britain after being convicted of passing nuclear secrets to the Soviet Union, died yesterday, the East German press agency A.D.N. reported. He was 76 years old.

- "Klaus Fuchs". TruTV. Archived from the original on 2003-02-02. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

His name was Klaus Emil Fuchs, and he was, as it has been shown by history, the most important atom spy in history. Not any of the notorious names in the saga of the theft of the atom bomb secrets Alan Nunn May, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, and David Greenglass had been as important to the Russian effort as Klaus Fuchs.

- "Trinity by Frank Close review – in pursuit of 'the spy of the century'". The Guardian. 17 August 2019. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- "1972 Death of Harry Gold Revealed". The New York Times. February 14, 1974. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

Harry Gold, who served 15 years in Federal prison as a confessed atomic spy courier, for Klaus Fuchs, a Soviet agent, and who was a key Government witness in the Julius and Ethel Rosenberg espionage case in 1951, died 18 months ago in Philadelphia.

- "Greenglass, in Prison, Vows to Kin He Told Truth About Rosenbergs". The New York Times. March 19, 1953. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

David Greenglass, serving fifteen years as a confessed atom spy, denied to members of his family recently that he had been coached by the Federal Bureau of Investigation in the drawing of segments of the atom bomb, or that he had given perjured testimony against his sister, Mrs. Ethel Rosenberg, and her husband, Julius.

- Cowell, Alan (November 10, 1999). "Theodore Hall, Prodigy and Atomic Spy, Dies at 74". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

Theodore Alvin Hall, who was the youngest physicist to work on the atomic bomb project at Los Alamos during World War II and was later identified as a Soviet spy, died on Nov. 1 in Cambridge, England, where he had become a leading, if diffident, pioneer in biological research. He was 74. ... Mr. Albright and Ms. Kunstel say Mr. Hall and a former Harvard roommate, Saville Sax, approached a Soviet trade company in New York in late 1944 and began supplying critical information about the atomic project.

- Joseph Albright & Marcia Kunstel (Sep. 14, 1997), "The Boy Who Gave Away The Bomb", The New York Times Magazine: “ ‘It has even been alleged that I “changed the course of history.” Maybe the “course of history,” if unchanged, could have led to atomic war in the past 50 years – for example the bomb might have been dropped [by the U.S.] on China in 1949 or the early ’50s. Well, if I helped to prevent that, I accept the charge. ...’ ”

- William J. Broad (Nov. 12, 2007), "A Spy's Path: Iowa to A-Bomb to Kremlin Honor", The New York Times p. A1

- John Earl Haynes; Harvey Klehr; Alexander Vassiliev (2010). Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-15572-3.

- Michael Walsh (May 2009), "George Koval: Atomic Spy Unmasked", Smithsonian

- John Earl Haynes; Harvey Klehr (2000). Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300084625 – via Google Books.

- "Alan Nunn May, 91, Pioneer In Atomic Spying for Soviets". The New York Times. 25 January 2003. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

Alan Nunn May, a British atomic scientist who spied for the Soviet Union, died on Jan. 12 in Cambridge. He was 91. ... One of the first Soviet spies uncovered during the cold war, Dr. Nunn May worked on the Manhattan Project and was betrayed by a Soviet defector in Canada. His arrest in 1946 led the United States to restrict the sharing of atomic secrets with Britain.

- "Execution of the Rosenbergs". The Guardian. London. June 20, 1953. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were executed early this morning at Sing Sing Prison for conspiring to pass atomic secrets to Russia in World War II.

- "The Rosenbergs: A Case of Love, Espionage, Deceit and Betray". TruTV. Archived from the original on 2003-02-02. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were charged with the crime of conspiracy to commit espionage, and tried under the Espionage Act of 1917.

- "Execution of the Rosenbergs". The Guardian. London. June 20, 1953. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were executed early this morning at Sing Sing Prison for conspiring to pass atomic secrets to Russia in World War II.

- Broad, William J. (2019-11-23). "Fourth Spy Unearthed in U.S. Atomic Bomb Project". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-11-28.

- "Morton Sobell Free As Spy Term Ends". The New York Times. January 15, 1969. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

Morton Sobell, sentenced to 30 years for a wartime espionage conspiracy to deliver vital national secrets to the Soviet Union, was released from prison yesterday after serving 17 years and 9 months.

- Roberts, Sam (September 11, 2008). "For First Time, Figure in Rosenberg Case Admits Spying for Soviets". The New York Times.

In an interview on Thursday, Mr. Sobell, who served nearly 19 years in Alcatraz and other federal prisons, admitted for the first time that he had been a Soviet spy.

- "Адамс Артур Александрович". www.warheroes.ru. Retrieved 2020-04-16.

Further reading

- Alexei Kojevnikov, Stalin's Great Science: The Times and Adventures of Soviet Physicists (Imperial College Press, 2004). ISBN 1-86094-420-5 (use of espionage data by Soviets)

- Gregg Herken, Brotherhood of the Bomb: The Tangled Lives and Loyalties of Robert Oppenheimer, Ernest Lawrence, and Edward Teller (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 2002). ISBN 0-8050-6588-1 (details on Fuchs)

- Richard Rhodes, Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995). ISBN 0-684-80400-X (general overview of Fuchs and Rosenberg cases)

- Nancy Greenspan, Atomic Spy: The Dark Lives of Klaus Fuchs (New York: Viking Press, 2020). ISBN 978-0-593-08339-0 (general biography of Fuchs)