Spark plug

A spark plug is an electrical device used in an internal combustion engine to produce a spark which ignites the air-fuel mixture in the combustion chamber. As part of the engine's ignition system, the spark plug receives high-voltage electricity (generated by an ignition coil in modern engines and transmitted via a spark plug wire) which it uses to generate a spark in the small gap between the positive and negative electrodes. The timing of the spark is a key factor in the engine's behaviour, and the spark plug usually operates shortly before the combustion stroke commences.

The spark plug was invented in 1860, however its use only became widespread after the invention of the ignition magneto in 1902. Diesel engines use compression ignition (instead of spark ignition), therefore they do not normally use spark plugs.

Design

The main elements of a spark plug are the shell, insulator, central electrode and side electrode (also known as "ground strap"). The main part of the insulator is typically made from sintered alumina (Al2O3), a hard ceramic material with high dielectric strength.[1][2][3] In marine engines, the shell of the spark plug is often a double-dipped, zinc-chromate coated metal.[4]

A spark plug passes through the wall of the combustion chamber, therefore it must also form part of the seal for the high-pressure gasses within the combustion chamber.

Electrodes

The central electrode is connected to the terminal through an internal wire. The central electrode setup as the cathode from where the electrons are ejected.[5] This is because the central electrode is usually the hottest part of the plug, and thermionic emission principles mean it is easier to eject electrons from a hotter surface.[6] The sharp tip of the central electrode also increases the electrical field strength, thus increasing the emission of electrons.[6] The side electrode (which is colder and blunter) requires up to 45 percent higher voltage,[6] therefore only wasted spark systems use the side electrode as the cathode.[7]

The side electrode is made from high-nickel steel and is welded or hot forged to the side of the metal shell.

Spark plugs can contain up to four side electrodes surrounding the central electrode. Multiple side electrodes generally provide longer life, as when the spark gap widens due to electric discharge wear, the spark moves to another closer ground electrode. The disadvantage of multiple side electrodes is that a shielding effect can occur for each electrode, leading to a less efficient burn and increased fuel consumption.

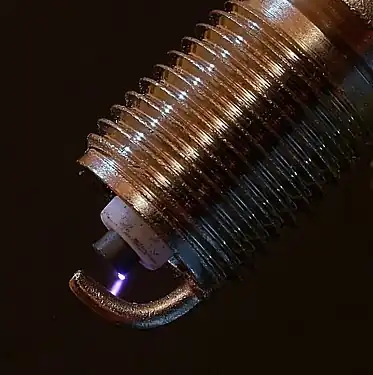

Central and side electrodes

Central and side electrodes An electric spark being generated between the electrodes

An electric spark being generated between the electrodes

Gap size

The distance between the tip of the spark plug and the central electrode is called the "spark plug gap" and is a key factor in the function of a spark plug. Spark plug gaps for car engines are typically 0.6 to 1.8 mm (0.024 to 0.071 in). Modern engines (using solid-state ignition systems and electronic fuel injection) typically use larger gaps than older engines that use breaker point distributors and carburetors.

Smaller plug gap sizes usually are more reliable at producing a spark, however the spark may be too weak to ignite the fuel-air mixture. A larger plug gap size will produce a stronger spark, however the spark might not always be produced (such as at high RPM). Gap adjustment is not recommended for iridium and platinum spark plugs, because there is a risk of damaging a metal disk welded to the electrode.[8]

Wasted spark applications

Wasted spark systems place a greater strain upon spark plugs since they alternately fire electrons in both directions (from the ground electrode to the central electrode, not just from the central electrode to the ground electrode). As a result, vehicles with such a system should have precious metals on both electrodes, not just on the central electrode, in order to increase service replacement intervals since they wear down the metal more quickly in both directions, not just one.[9]

Indexing of plugs

"Indexing" of plugs upon installation involves installing the spark plug so that the open area of the gap (i.e. the side not shrouded by the side electrode), faces the center of the combustion chamber. This is claimed to improve ignition by maximising the exposure of the fuel-air mixture to the spark in every cylinder.

Indexing is accomplished by either:

- Using thin washers to set the amount of thread engaged by the spark plug, thus determining the orientation of the spark plug within the cylinder head. This must be done individually for each plug, as the orientation of the gap with respect to the threads of the shell is usually random.

- Producing spark plugs with a specific orientation of the gap relative to the threads of the shell. These spark plugs and usually designated as such by a suffix to the part number of the spark plug.

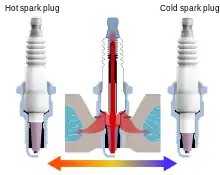

Heat range

An important factor for a spark plug is the temperature that the tip is designed to withstand, called the heat range. Typical heat ranges for passenger car engines are usually between 500 and 850 °C (932 and 1,562 °F).[10][11] A hotter spark plug has more insulation between itself and the cylinder head, causing less heat to be dissipated from the spark plug and therefore the spark plug remaining hotter.[12] Temperatures higher than 450 °C (842 °F) are needed to prevent carbon build-up on the spark plug, while temperatures over 800 °C (1,470 °F) can cause overheating of the plug.[13]

Switching to a higher heat range is sometimes used to compensate for fuel delivery or oil consumption problems, however this increases the risk of pre-ignition.[14]

History

Belgian-French engineer Étienne Lenoir is generally credited with the invention of the spark plug in 1860, due to its use in the early Lenoir gas engine.[15][16][17][18]

Several patents relating to electrical ignition systems were filed in the late 1890s, including from Serbian engineer Nikola Tesla,[19] British engineer Frederick Richard Simms[20] and German engineer Robert Bosch.[21] The use of high-voltage spark plugs in commercial viable engines was only made possible after 1902 however, due to the invention of magneto-based ignition systems by Bosch engineer Gottlob Honold. Early manufacturers of spark plugs included American company Champion,[22] British company Lodge brothers[23] and London-based KLG (who pioneed the use of mica as an insulator).

During the 1930s, American geologist Helen Blair Bartlett developed an alumina ceramic-based insulator for the spark plug.[24]

Polonium spark plugs were marketed by Firestone from 1940 to 1953. While the amount of radiation from the plugs was minuscule and not a threat to the consumer, the benefits of such plugs quickly diminished after approximately a month because of polonium's short half-life, and because buildup on the conductors would block the radiation that improved engine performance. The premise behind the polonium spark plug, as well as Alfred Matthew Hubbard's prototype radium plug that preceded it, was that the radiation would improve ionization of the fuel in the cylinder and thus allow the plug to fire more quickly and efficiently.[25][26]

See also

References

- "Denso's "Basic Knowledge" page". Globaldenso.com. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- The Bosch Automotive Handbook, 8th Edition, Bentley Publishers, copyright May 2011, ISBN 978-0-8376-1686-5, pp 581–585.

- Air Commodore F. R. Banks (1978). I Kept No Diary. Airlife. p. 113. ISBN 0-9504543-9-7.

- "Marine Spark Plug Savvy". MarineEngineDigest.com. 29 April 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- V.A.W., Hillier (1991). "74: The ignition system". Fundamentals of Motor Vehicle Technology (4th ed.). Stanley Thornes. p. 450. ISBN 0-7487-05317.

- International Harvester, Truck Service Manual TM 5-4210-230-14&P-1 - Electrical - Ignition Coils and Condensers, CTS-2013-E p. 5 (PDF page 545)

- NGK, Wasted Spark Ignition

- "How to Choose Proper Spark Plugs for Your Engine". VIN Sonar | help - Automotive Guides and Online Tools. 2022-01-27. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- See p. 824 of the 2015 Champion Master Catalog. http://www.fme-cat.com/catalogs.aspx Archived 2018-06-01 at the Wayback Machine

- "Spark Plug Heat Range". www.enginebuildermag.com. 20 May 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- "Guide to Understanding Spark Plug Heat Ranges". www.carfromjapan.com. 25 June 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- "10 factors that influence correct spark plug heat range for street and racing". www.motortrend.com. 9 July 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- "Spark Plug Basics". NGK Spark Plugs. 9 May 2019. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- "Understanding Spark Plug Heat Range". NGK Spark Plugs. 9 May 2019. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- "Madehow.com's "How a spark plug is made" page". madehow.com.

- "1886 Gas Engine patent #345,596 for Ettienne Jean Joseph Lenoir". Figure 6.

- Denton, Tom (2013). "Development of the automobile electrical system". Automobile Electrical and Electronic Systems (revised ed.). Routledge. p. 6. ISBN 9781136073823. Retrieved 2018-08-20.

1860[:] Lenoir produced the first spark-plug.

- Donnelly, Jim (January 2006). "Albert Champion". www.hemmings.com. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- Tesla, Nikola (16 August 1898). "Electrical Igniter For Gas-Engines". Retrieved 13 March 2023.

- "Who Invented The Spark Plug?". www.drivespark.com. 8 January 2022. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

- "1886-1905: From first workshop to factory". Bosch Global. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

- "A.S.E.C.C.'s History of Spark Plugs". www.asecc.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- "Lodge Plugs". Gracesguide.co.uk. 2011-08-30. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- "Women in Transportation - Automobile Inventions". wwwcf.fhwa.dot.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-06-23.

- "Radioactive spark plugs". Oak Ridge Associated Universities. January 20, 1999. Retrieved October 7, 2021.

- Pittman, Cassandra (February 3, 2017). "Polonium". The Instrumentation Center. University of Toledo. Retrieved August 23, 2018.