Holy Lance

The Holy Lance, also known as the Lance of Longinus (named after Saint Longinus), the Spear of Destiny, or the Holy Spear, is the lance that is alleged to have pierced the side of Jesus as he hung on the cross during his crucifixion.

Biblical references

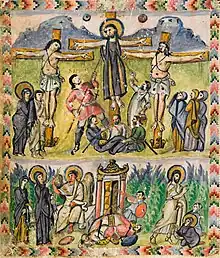

The lance (Greek: λόγχη, lonkhē) is mentioned in the Gospel of John,[1] but not the Synoptic Gospels. The gospel states that the Romans planned to break Jesus' legs, a practice known as crurifragium, which was a method of hastening death during a crucifixion. Because it was the eve of the Sabbath (Friday sundown to Saturday sundown), the followers of Jesus needed to "entomb" him because of Sabbath laws. Just before they did so, they noticed that Jesus was already dead and that there was no reason to break his legs ("and no bone will be broken"[2][lower-alpha 1]). To make sure that he was dead, a Roman soldier (named in extra-Biblical tradition as Longinus) stabbed him in the side.

One of the soldiers pierced his side with a lance (λόγχη), and immediately there came out blood and water.

Longinus

The name of the soldier who pierced Christ's side with a lonchē is not given in the Gospel of John, but in the oldest known references to the legend, the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus appended to late manuscripts of the 4th century Acts of Pilate, the soldier is identified as a centurion and called Longinus (making the spear's Latin name Lancea Longini).[3]: 6–8 [4]: 73

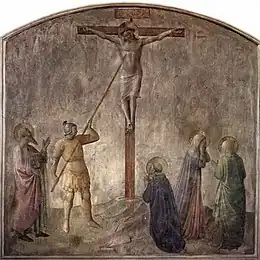

A form of the name Longinus occurs in the Rabula Gospels in the year 586. In a miniature, the name ΛΟΓΙΝΟΣ (LOGINOS) is written above the head of the soldier who is thrusting his lance into Christ's side. This is one of the earliest records of the name, if the inscription is not a later addition.[5]

Relics

At least four major relics are claimed to be the Holy Lance or parts of it.

Rome

A Holy Lance relic is preserved at Saint Peter's Basilica in Vatican City, in a loggia carved into the pillar above the statue of Saint Longinus.[6][7] The Catholic Church makes no claim as to its authenticity.

The first historical reference to a lance was made in AD 570 by an unknown pilgrim from Piacenza (often erroneously identified with St. Antoninus of Piacenza) in his descriptions of the holy places of Jerusalem, writing that he saw in the Basilica of Mount Zion "the crown of thorns with which Our Lord was crowned and the lance with which He was struck in the side",[8]: 18 [5] although there is uncertainty about the exact site to which he refers.[8]: 42 A lance is mentioned in the so-called Breviarius at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.[5] The alleged presence in Jerusalem of the relic is attested by Cassiodorus (c. 485–585) as well as by Gregory of Tours (c. 538–594), who had not actually been to Jerusalem.[9][10]

In 614, Jerusalem was captured by the Sasanian general Shahrbaraz.[11]: 156 The Holy Lance was among the relics captured, but one of Shahrbaraz's associates gave it to Nicetas who brought it to Constantinople later that year.[11]: 157 The lance was placed in the church of Hagia Sophia,[5] and later to the Church of the Virgin of the Pharos.[12]: 35

By 1244 the point of the lance was set in an icon.[5] Emperor Baldwin II sold the point and other relics to King Louis IX of France.[5][13]: 28–31 [14]: 307–308 The point of the lance was then enshrined with the crown of thorns in the Sainte Chapelle in Paris. During the French Revolution these relics were removed to the Bibliothèque Nationale but the point subsequently disappeared.[5]

As for the larger portion of the lance, Arculf claimed he saw it at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre around 670 in Jerusalem.[5] Some claim that the larger relic had been conveyed to Constantinople in the 8th century, possibly at the same time as the Crown of Thorns. At any rate, its presence at Constantinople seems to be clearly attested by various pilgrims, particularly Russians, and, though it was deposited in various churches in succession, it seems possible to trace it and distinguish it from the relic of the point.[5] Sir John Mandeville declared in 1357 that he had seen the blade of the Holy Lance both at Paris and at Constantinople, and that the latter was a much larger relic than the former.[5] It is worth adding that Mandeville is not generally regarded as one of the Middle Ages' most reliable witnesses, and his supposed travels are usually treated as an eclectic amalgam of myths, legends and other fictions.

"The lance which pierced Our Lord's side" was among the relics at Constantinople shown in the 1430s to Pedro Tafur, who added "God grant that in the overthrow of the Greeks they have not fallen into the hands of the enemies of the Faith, for they will have been ill-treated and handled with little reverence."[15]

Whatever the Constantinople relic was, it did fall into the hands of the Turks, and in 1492, Sultan Bayezid II sent it to Pope Innocent VIII to encourage the pope to continue to keep his brother and rival Cem prisoner.[16]: 311–318 [5] At this time great doubts as to its authenticity were felt at Rome, as Johann Burchard records,[17] because of the presence of other rival lances in Paris (the point that had been separated from the lance), Nuremberg (see Holy Lance in Vienna below), and Armenia (see Holy Lance in Echmiadzin below).[5] This relic has never since left Rome, and its resting place is at Saint Peter's.[5] Innocent's tomb, created by Antonio del Pollaiuolo, features a bronze effigy of the pope holding the spear blade he received from Bayezid.[16]: 321

In the mid-18th century Pope Benedict XIV states that he obtained from Paris an exact drawing of the point of the lance, and that in comparing it with the larger relic in St. Peter's he was satisfied that the two had originally formed one blade.[18]: 323

A mitred Adhémar de Monteil carrying one of the instances of the Holy Lance in one of the battles of the First Crusade

A mitred Adhémar de Monteil carrying one of the instances of the Holy Lance in one of the battles of the First Crusade 1898 drawing of the Holy Lance in Rome

1898 drawing of the Holy Lance in Rome

Vienna

The Holy Lance in Vienna is displayed in the Imperial Treasury or Weltliche Schatzkammer (lit. Worldly Treasure Room) at the Hofburg Palace in Vienna, Austria.[19] It is a typical winged lance of the Carolingian dynasty.[19] At different times, it was said to be the lance of Saint Maurice or that of Constantine the Great.[20]: 177, 181 [19] In the tenth century, the Holy Roman Emperors came into possession of the lance, according to sources from the time of Otto I (912–973).[20]: 178 In 1000, Otto III gave Bolesław I of Poland a replica of the Holy Lance at the Congress of Gniezno.[21]: 351 [22][20]: 178 f.7 In 1084, Henry IV had a silver band with the inscription "Nail of Our Lord" added to it. This was based on the belief that the nail embedded in the spear-tip was one that had been used for the Crucifixion of Jesus.[20]: 181 It was only in the thirteenth century that the Lance became identified with that of Longinus, which had been used to pierce Christ's side and had been drenched in water and the blood of Christ.[19]

In 1273, the Holy Lance was first used in a coronation ceremony. Around 1350, Charles IV had a golden sleeve put over the silver one, inscribed Lancea et clavus Domini (Lance and nail of the Lord).[23]: 5 In 1424, Sigismund had a collection of relics, including the lance, moved from his capital in Prague to his birthplace, Nuremberg, and decreed them to be kept there forever.[23]: 7–8 This collection was called the Imperial Regalia (Reichskleinodien).

When the French Revolutionary army approached Nuremberg in the spring of 1796, the local authorities turned over the Imperial Regalia to Johann Alois von Hügel, Chief Commissary of the Imperial Diet.[24]: 18–19 [25]: 732 Baron von Hügel took the regalia to Ratisbon for safekeeping, but by 1800 that city was also under threat of invasion, so he relocated them again to Passau, Linz, and Vienna.[24] When the French entered Vienna in 1805, the collection was moved again to Hungary, before ultimately returning to Vienna.[25]: 732 [24]: 19 These movements were conducted in secret, as the status of the regalia had not been resolved amid plans for the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire. When Nuremberg later appealed for the return of the regalia, the city's requests were easily dismissed by the Austrian Empire.[25]: 732

In Mein Kampf, Adolf Hitler wrote that the Imperial Insignia "were still preserved in Vienna and appeared to act as magical relics rather than as the visible guarantee of an everlasting bond of union. When the Habsburg State crumbled to pieces in 1918, the Austrian Germans instinctively raised an outcry for union with their German fatherland".[26] During the Anschluss, when Austria was annexed to Germany, the Nazis brought the Reichskleinodien to Nuremberg, where they displayed them during the September 1938 Party Congress. They then transferred them to the Historischer Kunstbunker, a bunker that had been built into some of the medieval cellars of old houses underneath Nuremberg Castle to protect historic art from air raids.[27]

Most of the Regalia were recovered by the Allies at the end of the war, but the Nazis had hidden the five most important pieces in hopes of using them as political symbols to help them rally for a return to power, possibly at the command of Nazi Commander Heinrich Himmler.[27] Walter Horn – a Medieval studies scholar who had fled Nazi Germany and served in the Third Army under General George S. Patton – became a special investigator in the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program after the end of the war, and was tasked with tracking the missing pieces down.[27] After a series of interrogations and false rumors, Nuremberg city councilor Stadtrat Fries confessed that he, fellow-councilman Stadtrat Schmeiszner, and an SS official had hidden the Imperial Regalia on 31 March 1945, and he agreed to bring Horn's team to the site.[27] On 7 August, Horn and a U.S. army captain escorted Fries and Schmeiszner to the entrance of the Panier Platz Bunker, where they located the treasures hidden behind a wall of masonry in a small room off of a subterranean corridor, roughly eighty feet below ground.[27] The Regalia were first brought back to Nuremberg castle to be reunited with the rest of the Reichskleinodien, and then transferred with the entire collection to Austrian officials the following January.[27]

The Kunsthistorisches Museum has dated the lance to the 8th century.[19] Robert Feather, an English metallurgist and technical engineering writer, tested it for a documentary in January 2003.[28][29] Based on X-ray diffraction, fluorescence tests, and other noninvasive procedures, he dated the main body of the spear to the 7th century at the earliest.[29] Feather stated in the same documentary that an iron pin – long claimed to be a nail from the crucifixion, hammered into the blade and set off by tiny brass crosses – was "consistent" in length and shape with a 1st-century AD Roman nail.[29]

Not long afterward, researchers at the Interdisciplinary Research Institute for Archeology in Vienna used X-ray and other technology to examine a range of lances, and determined that the Vienna lance dates from around the 8th to the beginning of the 9th century, with the nail apparently being of the same metal, and ruled out the possibility of it dating back to the 1st century AD.[30]

-3-2.jpg.webp) Holy Lance displayed in the Imperial Treasury at the Hofburg Palace in Vienna, Austria

Holy Lance displayed in the Imperial Treasury at the Hofburg Palace in Vienna, Austria Polish replica of the Holy Lance, Wawel Hill, Kraków

Polish replica of the Holy Lance, Wawel Hill, Kraków The inscription on the Holy Lance

The inscription on the Holy Lance

Vagharshapat

A Holy Lance is conserved in Vagharshapat (previously known as Echmiadzin), the religious capital of Armenia.[31]: 254–256 It was previously held in the monastery of Geghard. The first source that mentions it is a text Holy Relics of Our Lord Jesus Christ, in a thirteenth-century Armenian manuscript. According to this text, the spear which pierced Jesus was to have been brought to Armenia by the Apostle Thaddeus. The manuscript does not specify precisely where it was kept, but the Holy Lance gives a description that exactly matches the lance, the monastery gate (since the thirteenth century precisely), and the name of Geghardavank (Monastery of the Holy Lance).

In 1655, the French traveler Jean-Baptiste Tavernier was the first Westerner to see this relic in Armenia. In 1805, the Russians captured the monastery and the relic was moved to Tchitchanov Geghard, Tbilisi, Georgia. It was later returned to Armenia, and is still on display at the Manoogian museum in Vagharshapat, enshrined in a 17th-century reliquary.

Antioch

During the June 1098 Siege of Antioch, a monk named Peter Bartholomew reported that he had a vision in which St. Andrew told him that the Holy Lance was buried in the Church of St. Peter in Antioch.[32]: 241–243 After much digging in the cathedral, Bartholomew allegedly discovered a lance.[32]: 243–245 Despite the doubts of many, including the papal legate Adhemar of Le Puy, many of the crusaders credited the discovery of the lance for their subsequent victory in the Battle of Antioch, which broke the siege and secured the city.[32]: 247–249, 253–254 [12]: 34–35

Greek Orthodox sources indicate the veneration of a lance relic in Antioch as early as the 10th century. Historian Klaus-Peter Todt has suggested this relic could have been buried to hide it from Seljuk forces in 1084, allowing the crusaders to find it in 1098.[33]: 99

In the 18th century, Roman cardinal Prospero Lambertini claimed the Antiochian lance was a fake.

Literary

.jpg.webp)

The Holy Lance has been conflated with the bleeding lance depicted in the unfinished 12th century romance Perceval, the Story of the Grail by Chrétien de Troyes.[34]: 1–2 The story also refers to a javelot that has wounded the Fisher King, which may or may not be intended to be one and the same with the bleeding lance.[34]: 3 [35] Chrétien ascribes supernaturally destructive powers to the bleeding spear, which are inconsistent with any Christian tradition.[34]: 2, 6–7, 11–13, 17 Nevertheless, the continuations of Chrétien's poem attempted to explain the mysteries of the bleeding spear by identifying it with the lance from John 19:34.[34]: 14–15 [3]: 166 [36]: 79

Chrétien's Perceval was adapted by Wolfram von Eschenbach into the German epic Parzival.[37][38] Like Chrétien, Wolfram depicts the bleeding lance in a manner that cannot easily be reconciled with the spear of Longinus.[34]: 5 Parzival became the primary source for Richard Wagner's 1882 opera Parsifal, in which the Fisher King is wounded by the spear that pierced Jesus's side.[39]: 1, 16–20

In popular culture

- As an element in the Crucifixion narrative, the Holy Lance has been featured in films depicting the death of Jesus, such as La Vie et la passion de Jésus Christ (1903)[40] and The Passion of the Christ (2004).[41]

- Indiana Jones searches for the Holy Lance in the 1995 comic book series Indiana Jones and the Spear of Destiny, taking place in 1945.[42] The 2023 film Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny opens with Jones attempting to recover the Holy Lance from Nazi Germany in 1944, but Jones discovers that this lance is a fake.[43]

- The spear of Longinus plays a significant role in Robin Jarvis' novel series Tales from the Wyrd Museum.

- The Spear of Destiny is the main plot device in the 2004 television film The Librarian: Quest for the Spear.[44]

- The Spear of Longinus is briefly shown and mentioned in Hellboy (2004), when Professor Broom shows FBI Agent Myers around the Bureau of Paranormal Research and Defence.[45]

- The Spear of Destiny is a central plot point in the film Constantine (2005).[46]

- The Spear of Destiny is the main plot point in season 2 of Legends of Tomorrow.[47]

- An ancient and powerful spear-like weapon in the anime Neon Genesis Evangelion is named the Spear of Longinus in reference to the Holy Lance.[48]

- The "Longinuslanze Testament" is a holy relic weapon wielded by Reinhard Heydrich in the 2017 anime Dies Irae (TV series).

- The Spear of Longinus appears in Persona 2: Innocent Sin, during the climax of the game's story.[49]

- The Spear of Longinus appears in Wolfenstein 3D as a plot device in the first expansion pack of the game titled "Spear of Destiny".[42]

- The Spear of Longinus is a major plot feature of the French language novel "Quand les Anges s'en Mêlent" by Sabine Vliers.

- The Spear of Destiny is the main plot device in and the title of Season 4 Episode 13 of the TV show The Unit.

- The Spear of Destiny is an object of interest in the video game Tomb Raider: Chronicles.[50]

See also

Explanatory notes

- This verse is reference to Psalms 34:20 regarding the righteous person, and commandments concerning the paschal lamb in Exodus 12:46 and Numbers 9:12.

Citations

- John 19:31–37

- John 19:36

- Peebles, Rose Jeffries (1911). The Legend of Longinus in Ecclesiastical Tradition and in English Literature, and its connection with the Grail. Baltimore: J. H. Furst. Retrieved 29 July 2023 – via The Internet Archive.

- Hone, William (1926). The Lost Books of the Bible: being all the gospels, epistles, and other pieces now extant attributed in the first four centuries to Jesus Christ, His apostles and their companions, not included, by its compilers, in the authorized New Testament; and, the recently discovered Syriac mss. of Pilate's letters to Tiberius, etc. New York: Alpha House. Retrieved 27 July 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- Thurston, Herbert (1910). "The Holy Lance". Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 23 July 2023 – via New Advent.

- Olivié, Antonio (2017). "In the Footsteps of Christ in Rome". Jerusalem Cross: Annales Ordinis Equestris Sancti Sepulchri Hierosolymitani. Vatican City: Grand Magisterium of the Equesrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem. pp. 64–65. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 May 2022. Retrieved 8 August 2023.

- Kuhn, Albert (1916). Roma: Ancient, Subterranean, and Modern Rome. New York: Benziger Brothers. Retrieved 8 August 2023 – via Google Books.

- Stewart, Aubrey; Wilson, CW, eds. (1896). Of the Holy Places Visited by Antoninus Martyr (Circ. 560–570 A.D.). London: Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society. pp. 14. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- Cassiodorus, Magnus Aurelius (1865). "Expositio Psalmum LXXXVI" [Explanation of Psalm 86]. In Migne, Jacques Paul (ed.). Patrologia Latina (in Latin). Vol. LXX. Paris: Jacques Paul Migne. col. 621 – via Internet Archive.

Ibi manet lancea, quae latus Domini transforavit, ut nobis illius medicina succurreret.

[There [Jerusalem] remains the lance which pierced the Lord's side, that his medicine might help us.] - Gregory of Tours (1879). "De lancea, corona spinea, et columna." [The lance, crown of thorns, and pillar]. In Migne, Jacques Paul (ed.). Patrologia Latina (in Latin). Vol. LXXI. Paris: Jacques Paul Migne. col. 712 – via Internet Archive.

De lancea vero, arundine, spongia, corona spinea et columna, ad quam verberatus est Dominus et Redemptor Hierosolymis, dicendum.

[Let us speak about the lance, the reed, the sponge, the crown of thorns, and the pillar where our Lord and Redeemer was lashed, in Jerusalem.] - Chronicon Paschale 284-628 AD. Translated by Whitby, Michael; Whitby, Mary. 2007. Retrieved 4 August 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- Morris, Colin (1984). "Policy and vision: The case of the Holy Lance found at Antioch". In Gillingham, John; Holt, J. C. (eds.). War and Government in the Middle Ages: Essays in honour of J. O. Prestwich. Totowa, NJ: Boydell. pp. 33–45. Retrieved 27 July 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- Gibbon, Edward (1867). "Chapter LXI.". The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Vol. VII. London: Bell & Daldy. pp. 1–49. Retrieved 30 July 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- Klein, Holger A. (2004). "Eastern Objects and Western Desires: Relics and Reliquaries between Byzantium and the West". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. Dumbarton Oaks. 58: 283–314. doi:10.2307/3591389. JSTOR 3591389.

- Ross, Sir E. Denison; Power, Eileen, eds. (1926). Pero Tafur: Travels and Adventures (1435–1439). Translated by Letts, Malcolm. New York: Harper & Brothers. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- von Pastor, Ludwig (1901). Antrobus, Frederick Ignatius (ed.). The History of the Popes, from the Close of the Middle Ages. Vol. V (2 ed.). London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, & Co. Retrieved 4 August 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- Burchard, Johann (1910). The Diary of John Burchard of Strasburg Vol. I: A.D. 1483-1492. Translated by Matthew, Arnold Harris. London: Francis Griffiths. pp. 337–339. Retrieved 7 August 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- Benedict XIV (1840). "Book IV, Part II, Chapter XXXI". Doctrina de Servorum Dei Beatificatione et Beatorum Canonizatione (in Latin). Brussels: Societatis Belgicae. pp. 322–325. Retrieved 3 August 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- "Die Heilige Lanze" [The Holy Lance]. Kunsthistorisches Museum. Archived from the original on 6 August 2023. Retrieved 5 August 2023.

- Adelson, Howard L. (June 1966). "The Holy Lance and the Hereditary German Monarchy". The Art Bulletin. College Art Association. 48 (2): 177–192. doi:10.2307/3048362. JSTOR 3048362.

- Czajkowski, Anthony F. (July 1949). "The Congress of Gniezno in the Year 1000". Speculum. The University of Chicago Press. 24 (3): 339–356. doi:10.2307/2848012. JSTOR 2848012. S2CID 162927768.

- Gallus Anonymus (1851). "Chronicae Polonorum". In Pertz, Georg Heinrich (ed.). Scriptores (in Folio) 9: Chronica et annales aevi Salici. Monumenta Germaniae Historica (in Latin). Hanover. p. 429 – via dMGH.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Schleif, Corine; Schier, Volker (20 November 2018). "How was the Geese Book made?" (PDF). Opening the Geese Book. Arizona State University.

- Holzhausen, Adolf (1910). Guide to the Treasury of the Imperial House of Austria in the Imperial and Royal Palace in Vienna. Vienna. Retrieved 7 August 2023 – via Google Books.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Wilson, Peter H. (December 2006). "Bolstering the Prestige of the Habsburgs: The End of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806". The International History Review. Taylor & Francis, Ltd. 28 (4): 709–736. doi:10.1080/07075332.2006.9641109. JSTOR 40109811. S2CID 154316830.

- Hitler, Adolf (1939). Mein Kampf [My Struggle]. Translated by Murphy, James. Project Gutenberg of Australia. p. 21. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- Ueno, Rihoko (11 April 2014). "Recovering Gold and Regalia: a Monuments Man investigates". Archives of American Art. The Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 26 June 2018. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- Lunghi, Cheri (narrator), Spear of Christ, BBC/Discovery Channel, Atlantic Productions, 2003, archived from the original on 12 December 2004, retrieved 1 January 2007

- Bird, Maryann (8 June 2003). "Piercing An Ancient Tale: Solving the mystery of a Christian relic". Time. Archived from the original on 3 August 2003. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- "Der geheimnisvolle Kreuznagel". ZDF. 4 September 2004. Archived from the original on 12 November 2004. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- Ballian, Anna (2018). "Liturgical Objects from Holy Etchmiadzin". In Evans, Helen C. (ed.). Armenia: Art, Religion, and Trade in the Middle Ages. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 250–259. ISBN 9781588396600. Retrieved 4 August 2023 – via Google Books.

- Runciman, Steven (1971). A History of the Crusades, Volume I: The First Crusade and the Foundation of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 4 August 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- Weltecke, Dorothea (2006). "The Syriac Orthodox in the Principality of Antioch During the Crusader Period". In Ciggaar, Krijna Nelly; Metcalf, David Michael (eds.). Antioch from the Byzantine Reconquest Until the End of the Crusader Principality: Acta of the congress held at Hernen Castle in May 2003. East and West in the Medieval Mediterranean. Vol. I. Leuven: Uitgeverij Peeters & Department of Oriental Studies. pp. 95–124. Retrieved 29 July 2023 – via University of Konstanz.

- Brown, Arthur Charles Lewis (1910). "The Bleeding Lance". Publications of the Modern Language Association of America. XXV (1): 1–59. doi:10.2307/456810. JSTOR 456810. S2CID 163517936. Retrieved 27 July 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- Nitze, William A. (July 1946). "The Bleeding Lance and Philip of Flanders". Speculum. University of Chicago Press. 21 (3): 303–311. doi:10.2307/2851373. JSTOR 2851373. S2CID 162229439.

- Loomis, Roger Sherman (1991). The Grail: From Celtic Myth to Christian Symbol. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University. ISBN 9780691020754. Retrieved 7 August 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- Hatto, A. T. (April 1947). "Two Notes on Chrétien and Wolfram". The Modern Language Review. Modern Humanities Research Association. 42 (2): 243–246. doi:10.2307/3717233. JSTOR 3717233.

- Hatto, A. T. (July 1949). "On Chretien and Wolfram". The Modern Language Review. Modern Humanities Research Association. 44 (3): 380–385. doi:10.2307/3717658. JSTOR 3717658.

- Beckett, Lucy (1981). Richard Wagner: Parsifal. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29662-5 – via Internet Archive.

- Nonguet, Lucien (co-director); Zecca, Ferdinand (co-director) (1903). La Vie et la passion de Jésus Christ [The Life and the Passion of Jesus Christ] (Motion picture). Event occurs at 38:50. Retrieved 6 August 2023 – via YouTube.

- "The Passion of the Christ (2004) Parents Guide". IMDb. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

A guard then orders another guard to check if Jesus is alive. That guard reluctantly stabs a spear into Jesus's side, resulting in a lot of blood coming out.

- Schier, Volker; Schleif, Corine (2009). "The Holy Lance as Late Twentieth-century Subcultural Icon". In Tomaselli, Keyan; Scott, David (eds.). Cultural Icons. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press. pp. 103–134. Retrieved 27 July 2023 – via Academia.edu.

- "They Belong in a Museum: Prop Master Ben Wilkinson on the Treasures and Artifacts of Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny". Lucasfilm. 7 July 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- Lowry, Brian (30 November 2004). "The Librarian: Quest for the Spear". Variety. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- Leydon, Joe (28 March 2004). "Hellboy". Variety. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- Ebert, Roger (17 February 2005). "'Constantine' adrift between heaven and hell". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- Sava, Oliver (22 March 2017). "Legends Of Tomorrow needs Tolkien's help to save all of reality (and fails)". AV Club. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- Burrowes, Carter (12 September 2020). "Anime Arsenal: Evangelion's Holy Spear of Longinus, Explained". CBR.com. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- Guglielmo, Samuel (20 April 2020). "A Celebration of Video Games Where You Can Kill Hitler". TechRaptor. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- Fielder, Joe (20 November 2000). "Tomb Raider Chronicles Review". Gamespot. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

General and cited references

- Kirchweger, Franz, ed. (2005). Die Heilige Lanze in Wien: Insignie, Reliquie, "Schicksalsspeer" [The Holy Lance in Vienna: Insignia, Relic, "Spear of Destiny"] (in German). Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum.

- Kirchweger, Franz (2005). "Die Geschichte der Heiligen Lanze vom späteren Mittelalter bis zum Ende des Heiligen Römischen Reiches (1806)" [The History of the Holy Lance from the Later Middle Ages to the End of the Holy Roman Empire (1806)]. Die Heilige Lanze in Wien: Insignie, Reliquie, "Schicksalsspeer" [The Holy Lance in Vienna: Insignia, Relic, "Spear of Destiny"] (in German). Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum. pp. 71–110.

- Schier, Volker; Schleif, Corine (2005). "Die heilige und die unheilige Lanze. Von Richard Wagner bis zum World Wide Web" [The Holy and the Unholy Lance. From Richard Wagner to the World Wide Web]. Die Heilige Lanze in Wien: Insignie, Reliquie, "Schicksalsspeer" [The Holy Lance in Vienna: Insignia, Relic, "Spear of Destiny"] (in German). Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum. pp. 110–143. Retrieved 27 July 2023 – via Academia.edu.

- Schier, Volker; Schleif, Corine (2004). "Seeing and Singing, Touching and Tasting the Holy Lance. The Power and Politics of Embodied Religious Experiences in Nuremberg, 1424–1524.". In Petersen, Nils Holger; Cluver, Claus; Bell, Nicolas (eds.). Signs of Change. Transformations of Christian Traditions and their Representation in the Arts, 1000–2000. Amsterdam; New York: Rodopi. pp. 401–426. Retrieved 27 July 2023 – via Academia.edu.

- Sheffy, Lester Fields (1915). Use of the Holy Lance in the First Crusade (Thesis). University of Texas.

External links

- "Piercing an Ancient Tale" – An article by Maryann Bird in the European Edition of Time on British metallurgist Robert Feather's scientific examination of the Spear in Vienna.