Urethral sphincters

The urethral sphincters are two muscles used to control the exit of urine in the urinary bladder through the urethra. The two muscles are either the male or female external urethral sphincter and the internal urethral sphincter. When either of these muscles contracts, the urethra is sealed shut.

The external urethral sphincter originates at the ischiopubic ramus and inserts into the intermeshing muscle fibers from the other side. It is controlled by the deep perineal branch of the pudendal nerve. Activity in the nerve fibers constricts the urethra.

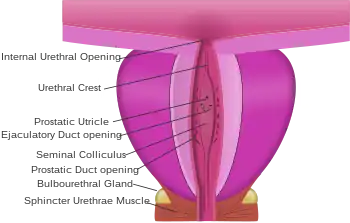

- The internal sphincter muscle of urethra: located at the bladder's inferior end and the urethra's proximal end at the junction of the urethra with the urinary bladder. The internal sphincter is a continuation of the detrusor muscle and is made of smooth muscle, therefore it is under involuntary or autonomic control. This is the primary muscle for prohibiting the release of urine.

- The female or male external sphincter muscle of urethra (sphincter urethrae): located in the deep perineal pouch, at the bladder's distal inferior end in females, and inferior to the prostate (at the level of the membranous urethra) in males. It is a secondary sphincter to control the flow of urine through the urethra. Unlike the internal sphincter muscle, the external sphincter is made of skeletal muscle, therefore it is under voluntary control of the somatic nervous system.[1]

Function and sex differences

In males and females, both internal and external urethral sphincters function to prevent the release of urine. The internal urethral sphincter controls involuntary urine flow from the bladder to the urethra, whereas the external urethral sphincter controls voluntary urine flow from the bladder to the urethra.[2] Any damage to these muscles can lead to urinary incontinence. In males, the internal urethral sphincter has the additional function of preventing the flow of semen into the male bladder during ejaculation.[3]

Females do have a more elaborate external sphincter muscle than males as it is made up of three parts: the sphincter urethrae, the urethrovaginal muscle, and the compressor urethrae. The urethrovaginal muscle fibers wrap around the vagina and urethra and contraction leads to constriction of both the vagina and the urethra. The origin of the compressor urethrae muscle is the right and left inferior pubic ramus and it wraps anteriorly around the urethra so when it contracts, it squeezes the urethra against the vagina. The external urethrae, like in males, wraps solely around the urethra.[4]

Congenital abnormalities of the female urethra can be surgically repaired with vaginoplasty.[5]

Clinical significance

The urethral sphincter is considered an integral part of maintaining urinary continence, and it is important to understand its role in some conditions:

- Stress urinary incontinence is a common problem related to the function of the urethral sphincter. Weak pelvic floor muscles, intrinsic sphincter damage, or damage to the surrounding nerves and tissue can make the urethral sphincter incompetent, and subsequently, it will not close fully, leading to stress urinary incontinence. In women, childbirth, obesity, and age can all be risk factors, especially by weakening the pelvic floor muscles.[6] In men, prostate surgery (prostatectomy, TURP, etc) and radiation therapy can damage the sphincter and cause stress incontinence.[7]

- Neurogenic bladder dysfunction can involve a malfunctioning urethral sphincter.[8]

- Urge incontinence can happen when the urethra can't hold the urine in as the bladder contracts uncontrollably.[9]

- Retrograde ejaculation can occur when the urethral sphincter fails to adequately contract during ejaculation.[3]

References

- Maclean, Allan; Reid, Wendy (2011). "40". In Shaw, Robert (ed.). Gynaecology. Edinburgh New York: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 599–612. ISBN 978-0-7020-3120-5; Access provided by the University of Pittsburgh

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Sam, Peter; Jiang, Jay; LaGrange, Chad (31 October 2022). "Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Sphincter Urethrae". StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29494045. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- Gupta S, Sharma R, Agarwal A, Parekh N, Finelli R, Shah R, Kandil H, Saleh R, Arafa M, Ko E, Simopoulou M, Zini A, Rajmil O, Kavoussi P, Singh K, Ambar RF, Elbardisi H, Sengupta P, Martinez M, Boitrelle F, Alves MG, Khalafalla K, Roychoudhury S, Busetto GM, Gosalvez J, Tadros N, Palani A, Rodriguez MG, Anagnostopoulou C, Micic S, Rocco L, Mostafa T, Alvarez JG, Jindal S, Sallam H, Rosas IM, Lewis S, AlSaid S, Altan M, Park HJ, Ramsay J, Parekattil S, Sabbaghian M, Tremellen K, Vogiatzi P, Gilani M, Evenson DP, Colpi GM (April 2022). "A Comprehensive Guide to Sperm Recovery in Infertile Men with Retrograde Ejaculation". The World Journal of Men's Health. 40 (2): 208–216. doi:10.5534/wjmh.210069. PMC 8987146. PMID 34169680.

- Netter, Frank H. (2019). Atlas of Human Anatomy, Seventh Edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier. ISBN 9780323393225.

- Hiort, O (2014). Understanding differences and disorders of sex development (DSD. Basel: Karger. ISBN 9783318025590; Access provided by the University of Pittsburgh

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Jung, Junyang; Ahn, Hyo Kwang; Huh, Youngbuhm (September 2012). "Clinical and Functional Anatomy of the Urethral Sphincter". International Neurourology Journal. 16 (3): 102–106. doi:10.5213/inj.2012.16.3.102. ISSN 2093-4777. PMC 3469827. PMID 23094214.

- Trost, Landon; Elliott, Daniel S. (2012). "Male Stress Urinary Incontinence: A Review of Surgical Treatment Options and Outcomes". Advances in Urology. 2012: 287489. doi:10.1155/2012/287489. ISSN 1687-6369. PMC 3356867. PMID 22649446.

- "Neurogenic Bladder: Symptoms, Diagnosis & Treatment - Urology Care Foundation". www.urologyhealth.org. Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- "Urinary Incontinence in Men | Michigan Medicine". www.uofmhealth.org. Retrieved 2020-04-14.

![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

External links

- Anatomy figure: 41:06-04 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Muscles of the female urogenital diaphragm (deep perineal pouch) and structures located inferior to it."