Spondylus

Spondylus is a genus of bivalve molluscs, the only genus in the family Spondylidae.[2] They are known in English as spiny oysters or thorny oysters (though they are not, in fact, true oysters).

| Spondylus Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

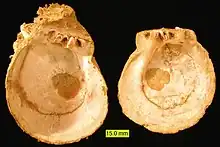

| A shell of Spondylus regius | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Bivalvia |

| Order: | Pectinida |

| Superfamily: | Pectinoidea |

| Family: | Spondylidae Gray, 1826 |

| Genus: | Spondylus Linnaeus, 1758[1] |

| Type species | |

| Spondylus gaederopus | |

| Species | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Description

The many species of Spondylus vary considerably in appearance. They are grouped in the same superfamily as the scallops.

They are not closely related to true oysters (family Ostreidae); however, they do share some habits such as cementing themselves to rocks rather than attaching themselves by a byssus. The two halves of their shells are joined with a ball-and-socket type of hinge, rather than with a toothed hinge as is more common in other bivalves. They also still retain vestigial anterior and posterior auricles ("ears", triangular shell flaps) along the hinge line, a characteristic feature of scallops, though not of oysters.

As is the case in all scallops, Spondylus spp. have multiple eyes around the edges of their mantle, and they have relatively well-developed nervous systems. Their nervous ganglia are concentrated in the visceral region, with recognisable optic lobes connected to the eyes.

Evolutionary history

The genus Spondylus appeared in the Mesozoic era, and is known in the fossil records from the Triassic Cassian beds in Italy (235 to 232 million years ago) onwards. About 40 extinct species are known.[3]

Fossils of these molluscs can be found in fossiliferous marine strata all over the world. For example, they are present in Cretaceaous rocks in the Fort Worth Formation of Texas, and in the Trent River Formation of Vancouver Island, as well as in other parts of North America.[4][5]

Distribution

Spiny oysters are found in all subtropical and (especially) tropical seas, usually close to the coasts.

Ecology

Spondylus are filter feeders. The adults live cemented to hard substrates, a characteristic they share, by convergent evolution, with true oysters and jewel boxes. Like the latter, they are protected by spines and a layer of epibionts and, like the former, they can produce pearls.[6] The type of substrate they use depends on the species: many only attach to coral, and the largest diversity of species is found in tropical coral reefs; others, (particularly S. spinosus) however, easily adapt to man-made structures, and have become important invasive species. Others still are often found attached to other shells, perhaps the most common belonging to the genus Malleus.

Uses

Archaeological evidence indicates that people in Neolithic Europe were trading the shells of S. gaederopus to make bangles and other ornaments throughout much of the Neolithic period.[7] The main use period appears to have been from around 5350 to 4200 BC.[7] The shells were harvested from the Aegean Sea, but were transported far into the center of the continent. In the LBK and Lengyel cultures, Spondylus shells from the Aegean Sea were worked into bracelets and belt buckles. Over time styles changed with the middle neolithic favouring generally larger barrel-shaped beads and the late neolithic smaller flatter and disk shaped beads.[7] Significant finds of jewelry made from Spondylus shells were made at the Varna Necropolis. During the late Neolithic the use of Spondylus in grave goods appears to have been limited to women and children.[7]

S. crassisquama is found off the coast of Colombia and Ecuador and has been important to Andean peoples since pre-Columbian times, serving as both an offering to the Pachamama and as currency.[8] In fact, much like in Europe, the Spondylus shells also reached far and wide, as pre-Hispanic Ecuadorian peoples traded them with peoples as far north as present-day Mexico and as far south as the central Andes.[9] The Moche people of ancient Peru regarded the sea and animals as sacred; they used Spondylus shells in their art and depicted Spondylus in effigy pots.[10] Spondylus were also harvested from the Gulf of California and traded to tribes through Mexico and the American Southwest.

Spondylus shells were the driving factor of trade within the Central Andes and were used in a similar manner to gold nuggets, copper hatches, coca, salt, red pepper, and cotton cloth.[11]

The use of Spondylus shells is what led to an economy of sorts in the Central Andes and led to the development of a merchant class, "mercardes", in different cultures within the Central Andes.[12] This caused the development of different styles of trade that went through evolutionary changes throughout pre-Columbian times. These are reciprocity (home based), reciprocity (boundary), down-the-line trade, central place (redistribution), central place (market exchange), emissary trading, and port of trade.[13] These modes of trade dictate the way that the Spondylus shells are traded, as well as who is benefiting the most from the trades. Modes such as central place (redistribution) require the entity that is the central place to be the one that gains the most benefit from the trade, and modes such as emissary trading and port of trade are the modes that started the "mercardes" class within the Central Andes.

The value of Spondylus shells in the Central Andes stems from supply and demand. There was a lot of demand for Spondylus shells due to the "fetishistic needs to the south".[14]

Even today, there are collectors of Spondylus shells, and a commercial market exists for them. Additionally, some species (especially S. americanus) are sometimes found in the saltwater aquariums.

S. limbatus was commonly ground for mortar in Central America, giving raise to its junior synonym, "S. calcifer".

Spondylus is fished primarily for its adductor muscle, or "callus", which is a high-value foodstuff.[15] Some Mediterranean species are edible and are commonly consumed, with S. gaederopus in particular being popular in Sardinia. Tropical species, however, tend to bioaccumulate saxitoxin.[16] The Romans ate them. Macrobius in Saturnalia III.13 describes a dinner party in 63 BCE in which there were two courses of Spondylus.

Aztec culture

In addition to its significance in the pre-Columbian times, Spondylus crassiquama was also an important part of Aztec culture. Spondylus uses amongst Aztecs included: art, jewelry, statues, religious motifs, and at times currency. One example of Spondylus used in art is the double-headed serpent which can be seen amongst images on the right of the page.

As stated above, Spondylus held immense religious value amongst Aztec culture pre-columbian times and is also a great representation of the relationship between the Aztec empire and nature. To Aztec groups and peoples’, Spondylus was a gift from the gods to be celebrated. Certain Spondylus groups were formed as a result of when and where they can be found seasonally and tend to connect a particular group of Spondylus to specific religious symbols such as the Sun god, the Moon goddess, and the mountain spirits. This led to certain groups of Spondylus being associated with seasonal weather events such as heavy rains or increases in sea temperature along the coast, as those events were closely associated with particular gods or spirits in Aztec culture .

Spondylus had several key uses in pre-Columbian Aztec history, most predominantly its importance in jewelry, art, and sculpture. Another use of Spondylus, that had to be done with extreme detail and precision, was to create breathtaking masks, vests, and other pieces individuals would use to express how valuable or wealthy they were in life and death. By having the most beautiful Spondylus pieces, meant that individual had immense power within the community.[17]

Species

Spondylidae taxonomy has undergone many revisions,[18] mostly due to the fact that identification is traditionally based on the shell only, and this is highly variable. To add to this, while some shallow-water species are extremely common, at least two deep-water ones are known from a single specimen, while a third (S. gravis)[19] was only rediscovered after 77 years. At least another common species (S. regius) has a different shell when it grows in deep water.[20]

- Spondylus americanus Hermann, 1781 - Atlantic thorny oyster

- Spondylus anacanthus Mawe, 1823 - nude thorny oyster

- †Spondylus aonis d'Orbigny, 1850

- Spondylus asiaticus Chenu, 1844

- Spondylus asperrimus G. B. Sowerby II, 1847

- †Spondylus aucklandicus P. Marshall, 1918

- Spondylus avramsingeri Kovalis, 2010

- † Spondylus bostrychites Guppy, 1867

- Spondylus butleri Reeve, 1856

- Spondylus candidus Lamarck, 1819

- Spondylus clarksoni Lamprell, 1992

- Spondylus concavus Deshayes in Maillard, 1863

- Spondylus crassisquama Lamarck, 1819

- Spondylus croceus Schreibers, 1793

- Spondylus darwini Jousseaume, 1882

- Spondylus deforgesi Lamprell & Healy, 2001

- Spondylus depressus Fulton, 1915

- Spondylus eastae Lamprell, 1992

- Spondylus echinatus Schreibers, 1793

- Spondylus erectospinosus Habe, 1973

- Spondylus exiguus Lamprell & Healy, 2001

- Spondylus exilis G. B. Sowerby III, 1895

- Spondylus fauroti Jousseaume, 1888

- Spondylus foliaceus Schreibers, 1793

- Spondylus gaederopus Linnaeus, 1758 - European thorny oyster

- Spondylus gloriandus Melvill & Standen, 1907

- Spondylus gloriosus Dall, Bartsch & Rehder, 1938

- † Spondylus granulosus Deshayes, 1830

- Spondylus gravis Fulton, 1915

- Spondylus groschi Lamprell & Kilburn, 1995

- Spondylus gussonii O. G. Costa, 1830

- Spondylus heidkeae Lamprell & Healy, 2001

- Spondylus imperialis Chenu, 1844

- Spondylus jamarci Okutani, 1983

- Spondylus Lamarckii Chenu, 1845

- Spondylus layardi Reeve, 1856

- Spondylus leucacanthus Broderip, 1833

- Spondylus limbatus G. B. Sowerby II, 1847

- Spondylus linguafelis G. B. Sowerby II, 1847

- Spondylus maestratii Lamprell & Healy, 2001

- Spondylus marinensis Cossignani & Allary, 2018

- Spondylus mimus Dall, Bartsch & Rehder, 1938

- Spondylus morrisoni Damarco, 2015

- Spondylus multimuricatus Reeve, 1856

- Spondylus multisetosus Reeve, 1856

- † Spondylus multistriatus Deshayes, 1830

- Spondylus nicobaricus Schreibers, 1793

- Spondylus occidens G. B. Sowerby III, 1903

- Spondylus ocellatus Reeve, 1856

- Spondylus orstomi Lamprell & Healy, 2001

- Spondylus ostreoides E. A. Smith, 1885

- Spondylus pratii Parth, 1990

- Spondylus proneri Lamprell & Healy, 2001

- Spondylus pseudogaederopus T. Cossignani, 2022

- Spondylus purpurascens T. Cossignani, 2022

- † Spondylus radula Lamarck, 1806

- Spondylus raoulensis W. R. B. Oliver, 1915

- † Spondylus rarispina Deshayes, 1830

- Spondylus reesianus G. B. Sowerby III, 1903

- Spondylus regius Linnaeus, 1758 - regal thorny oyster

- Spondylus rippingalei Lamprell & Healy, 2001

- Spondylus rubicundus Reeve, 1856

- Spondylus senegalensis Schreibers, 1793

- Spondylus sinensis Schreibers, 1793

- Spondylus spinosus Schreibers, 1793

- Spondylus squamosus Schreibers, 1793

- Spondylus tenellus Reeve, 1856

- Spondylus tenuis Schreibers, 1793

- Spondylus tenuispinosus G. B. Sowerby II, 1847

- Spondylus tenuitas Garrard, 1966

- Spondylus variegatus Schreibers, 1793

- Spondylus varius G. B. Sowerby I, 1827

- † Spondylus vaudini Deshayes, 1858

- Spondylus versicolor Schreibers, 1793

- Spondylus victoriae G. B. Sowerby II, 1860

- Spondylus violacescens Lamarck, 1819

- Spondylus virgineus Reeve, 1856

- Spondylus visayensis Poppe & Tagaro, 2010

- Spondylus zonalis Lamarck, 1819

- Spondylus echinus Jousseaume in Lamy, 1927 (taxon inquirendum)

- Spondylus imbricatus Perry, 1811 (nomen dubium)

- Spondylus microlepos Lamarck, 1819 (nomen dubium)

- Spondylus unicolor G. B. Sowerby II, 1847 (nomen dubium)

See also: Tikod amo, an undescribed species

References

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Editio decima, reformata. Laurentius Salvius: Holmiae. ii, 824 pp., available online at http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/10277#page/3/mode/1up

- MolluscaBase (2019). MolluscaBase. Spondylus Linnaeus, 1758. Accessed through: World Register of Marine Species at: http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=138518 on 2019-03-04

- "Fossilworks: Spondylus". fossilworks.org. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- Finsley, Chalres. 1999. A Field Guide to the Fossils of Texas. Gulf Publishing. Lanham, Maryland. plate 55.

- Ludvigsen, Rolf & Beard, Graham. 1997. West Coast Fossils: A Guide to the Ancient Life of Vancouver Island. pg. 104

- WingYan Ho, Joyce; Zhou, Chunhui. "Natural Pearls Reportedly from a Spondylus Species ("Thorny" Oyster)". GIA. Gemological Institute of America. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- Gardelková-Vrtelová, Anna; Golej, Marián (2013). "The necklace from the Strážnice site in the Hodonín district (Czech Republic). A contribution on the subject of Spondylus jewelry in the Neolithic". Documenta Praehistorica. Znanstvena založba Filozofske fakultete Univerze v Ljubljani. 40: 265–277. doi:10.4312/dp.40.21.

- Carter, Benjamin. "Spondylus in South American Prehistory" in Spondylus in Prehistory: New Data and Approaches. Ed. Fotis Ifantidis and Marianna Nikolaidou. BAR International Series 2216. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2011: 63-89.

- Shimada, Izumi. “Evolution of Andean Diversity: Regional Formations (500 B.C.E-C.E. 600). The Cambridge History of the Native People of the Americas. Vol. III, pt. 1. Ed. Frank Salomon & Stuart B. Schwartz. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999: 350-517, esp. "Mesoamerican-Northwest South American Connections", pp. 430-436.

- Katherine Berrin and Larco Museum. The Spirit of Ancient Peru: Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1997.

- "Political Economy, Ethnogenesis, and Language Dispersals in the Prehispanic Andes: A World-System Perspective". American Anthropologist.

- "Negotiated Subjugation: Maritime Trade and the Incorporation of Chincha Into the Inca Empire". The Journal of Island and Coastal Archeology.

- Martin, Alexander J. (2001). "The Dynamics of Pre-Columbian Spondylus Trade across the South American Central Pacific Coast" (PDF). Florida Atlantic University, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-06-19 – via ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

- Waves of Influence: Pacific Maritime Networks Connecting Mexico, Central America, and Northwestern South America.

- Lodeiros, César; Soria, Gaspar; Valentich-Scott, Paul; Munguía-Vega, Adrián; Cabrera, Jonathan Santana; Cudney-Bueno, Richard; Loor, Alfredo; Márquez, Adrian; Sonnenholzner, Stanislaus (August 2016). "Spondylids of Eastern Pacific Ocean". Journal of Shellfish Research. 35 (2): 279–293. doi:10.2983/035.035.0203.

- Montojo, U.M.; Sakamoto, S.; Cayme, M.F.; Gatdula, N.C.; Furio, E.F.; Relox, J.R.; Kodama, M. (2006). "Remarkable difference in toxin accumulation of paralytic shellfish poisoning toxins among bivalve species exposed to Pyrodinium bahamense var. compressum bloom in Masinloc bay, Philippines". Toxicon. 48 (1): 85–92. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.04.014. PMID 16777162. S2CID 26090723.

- Liu, Robert (2005-03-28). "Spondylus in Precolumbian, Historic and Contemporary Southwest Jewelry". Ornament. pp. 38–44 – via Academia.edu.

- WoRMS Editorial Board (2017). "Taxonomy". Spondylus. doi:10.14284/170. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Lamprell, Kevin L. (May 1998). "Recent Spondylus species from the Middle East and adjacent regions, with the description of two new species". Vita Marina. 45 (1–2): 58.

- Poppe, Guido T. "Spondylus regius, deep water". Shell Encyclopedia. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

External links

- Spondylidae pictures of the shells of most extant species.

- shells at the Rotterdam Natural History Museum

- Session Abstracts on Spondylus research at the 13th Meeting of the European Association of Archaeologists at Zadar, Croatia, September 2007

- Information about Spondylus from the website of the Gladys Archerd Shell Collection at Washington State University Tri-Cities Natural History Museum

- Article on "notched" Spondylus Neolithic artifacts in Europe

Bibliography

- A full and constantly updated bibliography on Spondylus spp. in Aegean, Balkan, European and American contexts

- Lamprell, Kevin L.: Spondylus: Spiny Oyster Shells of the World, E. J. Brill, Leiden, 1987 ISBN 90-04-08329-4