Spreite

Spreite, meaning leaf-blade in German (or spreiten, the plural form in German) is a stacked, curved, layered structure that is characteristic of certain trace fossils. They are formed by invertebrate organisms tunneling back and forth through sediment in search of food. The organism moves perpendicularly just enough at the start of each back-and-forth pass so that it avoids reworking a previously tunneled area, thereby ensuring that it only makes feeding passes through fresh, unworked sediment.[2][3]

Two types of spreiten are generally recognized. Protrusive spreiten result from movement of the organism away from its burrow entrance (i.e., a downward movement in vertical burrows), whereas retrusive spreiten result from movement towards the burrow entrance (i.e., an upward movement in vertical burrows).[3] Vertical burrows with retrusive spreiten are also referred to as "escape burrows", as they represent attempts by the organism during periods of high sedimentation to prevent the burrow entrance from being buried, and at the same time keep the bottom of the burrow at the same distance from the sediment-water interface.[4][5] In essence, the organism "escapes" from being buried too deeply by progressively tunneling upward, thereby leaving behind it a stacked vertical succession of concave-side-up spreite. Diplocraterion is the classic example of a vertical burrow with spreite,[6][7] whereas Rhizocorallium is an example of a horizontal burrow with spreite.[8]

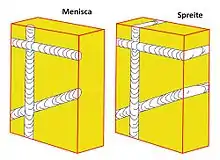

Spreiten differ from menisci, which are flat to slightly curved, back-filling structures found in some tubular burrows. Menisci are formed when the organism packs sediment, and sometimes fecal material as well, behind itself as it moves through the burrow.[1] Because spreiten and menisci represent different behaviors, the distinction between spreiten and meniscate burrows is an important criterion for the identification of certain ichnotaxa.[9] For example, generally parallel-sided, elongate, horizontal burrows with menisci are typically assigned to the Muensteria ichnospecies, whereas similar burrows with spreite will generally be assigned to the Rhizocorallium ichnogenus.[8][9]

See also

References

- Chamberlain, C.K. (1978). "Recognition of trace fossils in cores". In Basan, P.N. (ed.). Trace Fossil Concepts - SEPM Short Course No. 5. Oklahoma City: Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists. pp. 133–162.

- Bromley, R.G. (1996). Trace Fossils: biology, taphonomy and applications (2nd ed.). London: Chapman & Hall. pp. 11–12.

- Buatois, L.A. & Mángano, M.G. (2011). Ichnology: Organism-Substrate Interactions in Space and Time. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 31–33. ISBN 9781139500647.

- Frey, R.W. & Pemberton, S.G (1984). "Trace fossil facies models". In Walker, R. (ed.). Facies Models. Toronto, Ontario: Geological Association of Canada. pp. 189–207.

- Buatois, L.A. & Mángano, M.G. (2011). Ichnology: Organism-Substrate Interactions in Space and Time. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 9781139500647.

- Richter, Rudolf (1926). "Flachseebeobachtungen zur Paläontologie und Geologie. XII-XIV". Senckenbergiana. 8: 200–224.

- Fursich, F.T. (1974). "On Diplocraterion Torell 1870 and the significance of morphological features in vertical, spreiten-bearing, U-shaped trace fossils". Journal of Paleontology. 48 (5): 952–962. JSTOR 1303293.

- Fursich, F.T. (1974). "Ichnogenus Rhizocorallium". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 48 (1–2): 16–28. doi:10.1007/bf02986987.

- Howard. J.D. & Frey, R.W. (1984). "Characteristic trace fossils in nearshore to offshore sequences, Upper Cretaceous of east-central Utah". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 21 (2): 200–219. doi:10.1139/e84-022.