Serbian Progressive Party

The Serbian Progressive Party (Serbian Cyrillic: Српска напредна странка, romanized: Srpska napredna stranka, abbr. SNS) has been the ruling political party of Serbia since 2012. Miloš Vučević has served as its president since 2023.

Serbian Progressive Party Српска напредна странка Srpska napredna stranka | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | SNS |

| President | Miloš Vučević |

| Deputy President | Jorgovanka Tabaković |

| Vice-Presidents | |

| Parliamentary leader | Milenko Jovanov |

| Founders | |

| Founded | 8 September 2008 |

| Registered | 10 October 2008 |

| Split from | Serbian Radical Party |

| Headquarters | Palmira Toljatija 5/3, Belgrade |

| Newspaper | SNS Informator |

| Youth wing | Youth Union |

| Women's wing | Women Union |

| Membership (2020) | 800,000 |

| Ideology | |

| Political position | Big tent |

| National affiliation | Together We Can Do Everything |

| European affiliation | European People's Party (associate) |

| International affiliation | International Democrat Union |

| Colours | Blue |

| National Assembly | 99 / 250 |

| Assembly of Vojvodina | 68 / 120 |

| City Assembly of Belgrade | 39 / 110 |

| Party flag | |

| |

| Website | |

| sns | |

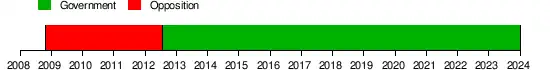

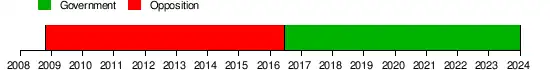

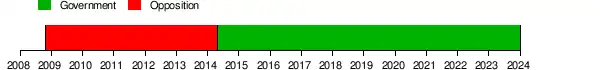

Founded by Tomislav Nikolić and Aleksandar Vučić in 2008 as a split from the Serbian Radical Party, SNS served in opposition to the Democratic Party until 2012. SNS gained prominence and became the largest opposition party due to their anti-corruption platform and the protests in 2011 at which they demanded early elections. In 2012, Nikolić was elected president of Serbia and succeeded by Vučić as president of SNS. A coalition government led by SNS and Socialist Party of Serbia (SPS) was also formed. Vučić became prime minister in 2014 while SNS became the largest party in Belgrade and Vojvodina in 2014 and 2016 respectively.

SNS chose Vučić as their presidential candidate for the 2017 election, which he ultimately won. Mass protests were organised following his election, while Ana Brnabić, an independent who later joined SNS, succeeded him as prime minister. SNS was later faced with protests from 2018 to 2020 and gained a supermajority of seats in the National Assembly of Serbia after the 2020 election which was boycotted by most opposition parties. The Serbian Patriotic Alliance merged into SNS in 2021 while environmental protests were also organised in 2021 and 2022. Vučić was re-elected as president in 2022, while SNS has continued to lead the government with SPS. A year later, Vučić was succeeded by Vučević as president of SNS.

Political scientists have described SNS as a populist and catch-all party that has a weak ideological profile or that is non-ideological. SNS supports Serbia's accession to the European Union but its support is rather pragmatic. An economically neoliberal party, SNS has pushed for austerity, market economy reforms, privatisation, economic liberalisation, and has reformed wages, pensions, the labour law, introduced a lex specialis for Belgrade Waterfront, and reformed the Constitution in the part related to judiciary. Critics have assessed that after it came to power, Serbia has suffered from democratic backsliding into authoritarianism, as well as a decline in media freedom and civil liberties. As of 2020, SNS has at least 800,000 members and it is the largest political party by membership in Europe.

History

Formation

The conflict between Tomislav Nikolić and Vojislav Šešelj came to light after Nikolić's statement that the Serbian Radical Party (SRS), a far-right political party,[1] in the National Assembly would support the Stabilisation and Association Process agreement for the accession of Serbia to the European Union; Nikolić's statement was met with the resistance from Šešelj and his supporters.[2][3][4] Nikolić, who was the head of the SRS parliamentary group and a deputy president of the party since 1992, resigned from these posts on 7 September 2008.[3] A day later, Nikolić formed the "Forward, Serbia" parliamentary group with 10 other MPs;[5] five more MPs joined the parliamentary group in the following days.[6][7] Božidar Delić and Jorgovanka Tabaković, high-ranking members of SRS, were one of the founding members of the parliamentary group.[5]

On 11 September, Nikolić announced that the "Forward, Serbia" parliamentary group would transform itself into a political party.[8][9] It was speculated that Aleksandar Vučić, the general-secretary of SRS, would join the newly formed party; Nikolić later that day confirmed that he would join the party.[8] A day later, SRS dismissed Nikolić and 17 other MPs from the party due to their opposition to Šešelj, while Vučić left SRS on 13 September.[10][11] Nikolić stated that the newly formed party would be the party of the "modern right", whilst supporting strengthening relations with the European Union and Russia.[11] On 24 September, Nikolić announced that the party would be called the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS).[12][13] SNS was registered as a political party on 10 October, while the founding convention was held on 21 October, at which a 20-man presidency was presented with Nikolić as the president and Vučić as deputy president.[14][15] During the period of its formation, SNS gained 21 members in the National Assembly in total and members of local chapters of SRS switched their affiliation to SNS.[16][17][18][19]

2008–2011

.jpg.webp)

In November 2008, SNS called for snap parliamentary elections to be held by October 2009;[20] this proposal was also later supported by Čedomir Jovanović, leader of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP).[21] Later that month, Vučić stated that SNS would act in opposition to the Democratic Party (DS).[22] SNS opposed the DS initiative regarding constitutional changes in May 2009, which it described as "frivolous".[23] A month later, SNS took part in local elections in Zemun, a Belgrade municipality known for being the stronghold of SRS; SNS won 34% of the popular vote, while SRS only won 10%.[24] By July 2009, SNS established itself as the strongest opposition party in Serbia.[25] SNS took part in local elections in Voždovac and Kostolac in December 2009;[26] in Voždovac, it won 37% of the popular vote and 26 seats in the Local Assembly, while in Kostolac it won 12% of the popular vote.[27][28] Following the elections, SNS formed a local government with the Democratic Party of Serbia (DSS) and New Serbia (NS) in Voždovac.[29] CeSID, a non-governmental and electoral monitoring organisation, argued that the reason behind their electoral success was due to their anti-corruption promises.[30]

SNS announced in February 2010 that it collected over 500,000 signatures in favour of snap parliamentary elections;[31] a month later, it claimed that the number grew to over a million signatures.[32] After March 2010, SNS claimed that DS "was pulling the country into a deep crisis", and that in response it would organise anti-government protests in Belgrade.[33][34] SNS declaratively supported the Srebrenica Declaration and condemned the victims of the 1995 massacre in Srebrenica, although it abstained from voting in the National Assembly in March 2010.[35][36] SNS announced in December 2010, that it would organise protests in February 2011;[37] New Serbia also said that it would join the protests.[38] SNS handed over 304,580 signatures in favour of changing the constitution in January 2011.[39] A series of anti-government protests that were organised by SNS began in February 2011.[40][41] SNS demanded the government to call snap elections by December 2011.[42][43][44] Initially the protests were held in Belgrade, although they spread throughout other locations in Serbia in March and April 2011.[45][46][47] Nikolić went on a hunger strike in mid-April, after demanding president Boris Tadić to call snap parliamentary elections.[48]

2012–2013

.JPG.webp)

Back in November 2010, SNS signed a cooperation agreement with New Serbia and two other parties, the Movement of Socialists (PS) and Strength of Serbia Movement (PSS).[49] The parties later held a meeting in February 2011 and took part together in protests that were organised by SNS.[50][51] The protests played a role in boosting the popularity of SNS, while opinion polls had showed that SNS received more support from voters than DS.[52][53] Due to the anti-government protests, President Tadić called for general elections to be held in spring of 2012.[54][55] In January 2012, it was confirmed that SNS would take part in a joint parliamentary list together with NS, PS, PSS, and eight minor parties and associations.[56][57] The coalition was later named "Let's Get Serbia Moving".[58] Nikolić was chosen as the presidential candidate of SNS, while Tabaković was chosen as the candidate for prime minister.[59][60]

During the campaign period, SNS criticised DS whilst campaigning on a pro-European platform, as well as promising to "correct the mistakes of DS".[52] Rudy Giuliani, the former mayor of New York City, met with Nikolić and Vučić during the campaign period in Belgrade to consult for them.[61][62] In the parliamentary election, the SNS-led coalition topped at the first place with 25% of the popular vote and won 73 seats in the National Assembly; SNS itself won 55 seats.[63][64] Nikolić accused DS of vote fraud; during a press conference he showed a bag with about three thousand ballots that were allegedly thrown into a trash can.[52] In the presidential election, Nikolić ended up in the second run-off against President Tadić; Nikolić ended up winning.[65] SNS did not receive the highest number of votes in the provincial and Belgrade City Assembly elections, and was unable to form governments in Vojvodina and Belgrade.[66][67] On 24 May 2012, Nikolić resigned as the president of SNS and was succeeded by Vučić, who was then later elected in September 2012;[68][69] Tabaković was also elected deputy president.[69]

Nikolić held consultations with parliamentary parties after the election.[70] After the consultations, Ivica Dačić, the leader of the Socialist Party of Serbia (SPS), was given the mandate to form a government.[52][71] Dačić reached a deal with SNS and the United Regions of Serbia (URS) and on 27 July the new government was sworn in.[72][73][74] Vučić became the first deputy prime minister.[75] After becoming the first deputy prime minister, Vučić entered into a conflict with oligarch businessman Miroslav Mišković; he claimed that Mišković allegedly "gained illegal profit" in the 2000s.[76] Mišković was arrested in December 2012 on suspicion of corruption,[77][78] although in July 2013 he was released from custody.[79] In October 2012, it was reported that SNS had over 330,000 members.[80] The People's Party (NP), led by former mayor of Novi Sad Maja Gojković, merged into SNS in December 2012.[81] By February 2013, SNS received over 40% of support in opinion polls, while DS, now in opposition, had 13% of support.[82]

In July 2013, SNS and SPS concluded that they would continue leading the government without URS;[83][84] the SNS–SPS government was then reshuffled in early September 2013.[85] Veroljub Arsić, who served as the head of the SNS parliamentary group, was replaced by Zoran Babić in August 2013.[86] A month later, Dragan Đilas, the mayor of Belgrade, was dismissed after a vote of no confidence that was called by SNS and DSS; SPS and the Party of United Pensioners of Serbia (PUPS) also voted in support of the vote.[87] Guy de Launey, a BBC News correspondent, Dragoljub Žarković, the co-founder of the Vreme newspaper, and journalist Koča Pavlović, stated that Vučić held the most influence and power in the government due to his status as the president of the largest party in the coalition government.[88][89][90] Freedom House, a non-profit research organisation, noted that the efforts to curb corruption during 2013 received mixed results.[91]: 546

2014–2016

.jpg.webp)

SNS held an assembly on 26 January 2014 at which Vučić was re-elected unopposed as the party's president.[92] At the assembly, he proposed to "test the will of the people" and called for a snap parliamentary election.[92][93] President Nikolić dissolved the National Assembly on 29 January and set the parliamentary election to be held on 16 March 2014.[94] In February, SNS presented its ballot list under the name "Future We Believe In".[95] Additionally, it was announced that the Social Democratic Party of Serbia (SDPS), Serbian Renewal Movement (SPO), and Christian Democratic Party of Serbia (DHSS) would appear on its list, alongside NS, PS, and PSS, who appeared on the SNS list in 2012.[95][96] SNS campaigned on its anti-corruption platform,[97] although Aleksandar Pavković, a Macquarie University professor, noted that there was no evidence that the platform decreased corruption.[98] SNS also based its platform on criticising its opponents, especially DS.[99] In the parliamentary election, the SNS-led coalition won a majority of 158 seats in the National Assembly.[100] Simultaneously, the City Assembly elections were held in Belgrade, in which the SNS-led coalition won 63 out of 110 seats.[101] Siniša Mali, an independent nominated by SNS, was elected mayor of Belgrade on 24 April 2014.[102] Vučić was elected and sworn in as prime minister three days later.[103] His first cabinet was mostly composed of SNS and SPS individuals.[104][105]: 4 A United States Agency for International Development (USAID) report noted that the SNS now had "complete political dominance" due to the status of Vučić as prime minister.[106] BBC News described the victory as an "unprecedented event".[107]

In October 2014, Radomir Nikolić, the son of President Nikolić, was brought to power in Kragujevac, the fourth largest city in Serbia by population, after successfully removing Veroljub Stevanović from power after a vote of no confidence.[108][109] By early 2015, SNS reported that it had around 500,000 members.[110] Since coming to power, no major protests in Serbia were held until the anti-government protests in April 2015.[111] The Do not let Belgrade drown (NDB) initiative, which headed the protests, opposed the Belgrade Waterfront, an urban development project headed by the Government of Serbia;[112] one of its representatives described it as a "big scam".[113][114] The project previously received criticism, with Milan Nešić, a Radio Free Europe journalist, describing it as a "pre-election trick".[115] The protests lasted up to September 2015.[116] After the cuts in public sector, protests were also held in December 2015.[99][117] Freedom House criticised the SNS-led government by stating that it displayed "a sharp intolerance for any kind of criticism either from opposition parties, independent media, civil society, or even ordinary citizens".[118]

In January 2016, Vučić announced that parliamentary elections will be held in April 2016.[119] Der Standard, an Austrian daily newspaper, stated that "[Vučić] now has an absolute majority, and he wants to ensure it for the next four years".[120] Vučić stated that the reason behind the snap election was to "ensure a fresh mandate to push European Union accession".[121] SNS began its campaign in late February 2016.[122] In early March, President Nikolić dissolved the National Assembly and scheduled the parliamentary elections for 24 April 2016.[123][124] This time, SNS took part under the "Serbia Is Winning" banner, while individuals from the Party of United Pensioners of Serbia (PUPS) and Serbian People's Party (SNP) were also present on its ballot list, including individuals from parties that took part with SNS in the 2014 election.[125][126] It was also reported that Aleksandar Martinović would replace Babić as the head of the SNS parliamentary group.[127] During the campaign, SNS expressed its support for the European Union and military neutrality, while maintaining cooperation with NATO, and ensuring economic reforms and a Western-type economy.[128] The Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) noted that billboards and posters that promoted SNS were dominant during the campaign.[105]: 10 In the parliamentary election, the SNS-led coalition won a majority of 131 seats in the National Assembly.[105]: 26 [129] Simultaneously, the provincial election was held in Vojvodina, in which SNS won 63 out of 120 seats in the Assembly of Vojvodina.[130] Florian Bieber, a Luxembourgian political scientist, noted that "the landslide victory did not come as a surprise".[131] DS, DSS, the Social Democratic Party (SDS), Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), League of Social Democrats of Vojvodina (LSV), Dveri, and Enough is Enough (DJB), all whom were in opposition to SNS, claimed that SNS allegedly stole the elections.[132]

Shortly after the election, opposition parties organised a protest in Belgrade.[133] Another series of anti-government protests began in Belgrade in May 2016 after the demolition of private objects in Savamala, an urban neighbourhood in Belgrade where the Belgrade Waterfront project is supposed to be built.[134] The NDB initiative organised the protests which ended up lasting until October 2016.[135][136] Vučić was re-elected president of SNS in May 2016.[137] Igor Mirović was elected president of the Government of Vojvodina in June 2016.[138] Vučić was given the mandate by President Nikolić to form a government, which he did with SPS in August 2016.[139][140] Ana Brnabić, an openly lesbian and independent politician, was appointed minister in the Vučić's cabinet.[140][141] In December 2016, Vučić affirmed that he would not run in the 2017 presidential election, although he also stated that the main body of SNS would decide its presidential candidate.[142]

2017–2019

In January 2017, President Nikolić stated that he would want to run for re-election,[143] although ministers such as Zorana Mihajlović and Aleksandar Vulin persuaded Vučić to run instead.[144][145] A month later, SNS announced Vučić as its presidential candidate.[146] Vučić received support from the coalition partners of SNS, and SPS, Alliance of Vojvodina Hungarians (VMSZ), and United Serbia (JS).[147] During the campaign period, it was reported that major newspapers, such as Alo!, Blic, Večernje novosti, Politika, Dnevnik, Kurir, and Srpski telegraf, printed campaign posters of SNS on its front pages; Voice of America reported it as an "unprecedented move".[148] Vučić campaigned on raising living standards, selling or shutting down state-owned companies, and austerity cuts.[149] Robert Creamer, an American political consultant, criticised him and stated that "Vučić would be in a position to select a prime minister of his choice, [and] control the judiciary, and the election apparatus — eliminating all checks and balances in the Serbian government".[150] In the presidential election, Vučić won 55% of the popular vote in the first run-off.[151]

Shortly after his election, mass protests erupted in Belgrade, Novi Sad, Niš, and other locations in Serbia.[152][153][154] The protests lasted until Vučić's inauguration, which occurred on 31 May 2017.[155] In June 2017, Vučić proposed Brnabić as prime minister.[156] She was sworn in on 29 June 2017.[157] Radio Free Europe noted that even though the presidency is a ceremonial role, Vučić has retained de facto power of SNS,[158] while the Belgrade Centre for Human Rights claimed that the political system de facto turned into a presidential one, similar to the era of Slobodan Milošević.[159]: 25 Zoran Panović, a journalist for Danas, reported that by October 2017 SNS was close to reaching 600,000 members.[160]

SNS announced its participation in the 2018 Belgrade City Assembly election under the "Because We Love Belgrade" banner in January 2018.[161] Zoran Radojičić, a paediatric surgeon, was chosen to be the first candidate on its ballot list.[162] At a conference in Belgrade Youth Center in February 2018, its ballot list candidates and election programme were presented.[163] In the City Assembly election, SNS won 64 seats.[164] CRTA, a non-governmental organisation, noted that SNS mostly criticised opposition politicians during the campaign period.[165] Radojičić replaced Mali and was appointed mayor in June 2018.[166]

In July 2018, political scientist Boban Stojanović noted that SNS had around 700,000 members.[167] A series of anti-government protests, dubbed 1 of 5 million, began in December 2018 after an assault on Borko Stefanović, an opposition politician.[168] The demonstrators criticised Vučić and SNS, demanded the end to political violence and stifling media freedom and freedom of expression.[169][170] The protests, which were attended by tens of thousands, continued into 2019.[169][171] In January 2019, SNS organised a meeting in support of Vladimir Putin's visit to Belgrade.[172][173] A month later, SNS launched a campaign named "Future of Serbia", in contrary to the anti-government protests.[174][175] Journalist Slobodan Georgiev noted that the campaign effectively silenced the protests.[176] Prime Minister Brnabić joined SNS in October 2019.[177]

2020–2022

In January 2020, Vučić announced that the electoral threshold would be lowered to 3 percent.[178] Critics saw this as a way that SNS would allow the alleged "controlled opposition" to enter the National Assembly.[178] SNS announced in February 2020 that it would take part under the "For Our Children" banner in the 2020 parliamentary election, stating that more than 50 percent of its ballot list would be comprised young people.[179] The SNS-led ballot list was sent over to the Republic Electoral Commission (RIK) on 5 March,[180] although the government postponed the election on 16 March due to the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in Serbia.[181] Initially supposed to be held on 26 April, the election was postponed to 21 June 2020.[182] In the same month, the anti-government protests which began in December 2018, formally ended in March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[183] The Alliance for Serbia (SzS), the major opposition alliance, announced that it would boycott the election, claiming that the elections would not be free and fair.[184][185] Freedom House labelled Serbia as a hybrid regime in May 2020, citing alleged "increased state capture, abuse of power, and terror tactics" by Vučić.[186] In June 2020, newspaper Danas reported that SNS had over 800,000 members.[187]

In the parliamentary election, the SNS-led coalition won a supermajority of 188 seats;[188] ignoring minority parties, SNS, the SPS–JS coalition, and the Serbian Patriotic Alliance (SPAS) only crossed the electoral threshold.[189] Vučić described it as a "historical moment".[190] Journalist Milenko Vasović saw the SNS election campaign as a promotion of Vučić and not the party itself.[191] Simultaneously, a provincial election was held in Vojvodina in which SNS also won a supermajority of 76 seats.[192] CeSID concluded that the election was met with "minimum democratic standards",[193] while OSCE characterised that the election was met with political polarisation.[194] Bieber described it as a pyrrhic victory for SNS and noted that the incoming legislation would not include opposition parties.[195] Journalist Patrick Kingsley stated that the election could allow "for greater momentum in peace talks with Kosovo".[196]

After gaining a supermajority in the National Assembly, the government of Serbia submitted a constitutional amendment regarding judiciary.[197] In early July 2020, a series of protests and riots against the government and the announced tightening of measures due to the spread of COVID-19 began in Belgrade.[198] It was reported that demonstrators took a peaceful approach in the protests, although that a group of far-right demonstrators also stormed the building of the National Assembly; the police shortly after cleared the building, although the clashes continued outside.[199][200][201] The government responded by taking a violent approach towards the demonstrators.[200][202] The protests lasted until the first constitutive session of the post-2020 election legislation, which occurred on 3 August 2020.[203][204] After the first constitutive session, the SNS parliamentary group changed its name to "Aleksandar Vučić – For Our Children".[205] Prime Minister Brnabić was re-elected in October 2020, while her new cabinet was mostly composed of members of SNS, SPS, and SPAS.[206] The National Assembly adopted the proposal for constitutional changes in December 2020.[207]

Vučić announced in early May 2021 that he submitted a proposal to merge SPAS into SNS.[208] Aleksandar Šapić, the leader of SPAS, stated that he supported the proposal.[209] The merge was completed on 26 May, after which Šapić was appointed vice-president of SNS while SPAS MPs joined SNS in June 2021.[210][211][212] Dialogues to improve election conditions between government and opposition parties, in which SNS took part, began in May 2021 and lasted until late October 2021.[213][214] A series of environmental protests began in September 2021 due to the concerns about the Project Jadar, a lithium mining project headed by Rio Tinto, an Anglo-Australian mining company.[215] The Government of Serbia supported the Project Jadar,[216] whilst SNS also officials criticised the protests.[217][218] The protests lasted until 15 February 2022.[219] The government of Serbia adopted changes for the law on referendum and people's initiative on 10 November 2021.[220] The changes received criticism due to the abolishment of the 50 percent turnout that was needed for referendums to pass.[221][222] At the end of the November 2021, Vučić was re-elected president of SNS.[223] In January 2022, a constitutional referendum was held.[224] A majority of 60% of voters voted in favour of proposed changes,[224] an option which was supported by SNS.[225]

In preparation for the 2022 general election, SNS and SPS announced that they would not run on a joint parliamentary list but that SPS would support the presidential candidate of SNS.[226] Additionally, SNS announced Šapić as its mayoral candidate for the Belgrade City Assembly election.[227] The National Assembly was dissolved in February 2022 to call snap parliamentary elections; presidential elections were called next month.[228][229] In the 2022 election, SNS took part under the "Together We Can Do Everything" banner,[230] while Vučić was announced as the presidential candidate of SNS in March 2022.[231] Transparency Serbia noted that SNS had a significant domination in the media during the campaign period, while CRTA alleged that the campaign period was met in worse conditions than in 2020.[232][233] In the presidential election, Vučić was re-elected after winning 60% of the popular vote, while in the parliamentary election, the SNS-led coalition won 120 seats.[234][235] In the Belgrade City Assembly election, the SNS-led coalition won 48 seats.[236] Šapić was elected mayor of Belgrade in June 2022.[237] Milenko Jovanov was appointed head of the SNS parliamentary group in August 2022, replacing Martinović, who was its head since 2016.[238] Later that month, Prime Minister Brnabić was given another mandate to form a government.[239] The composition of her third cabinet was announced on 23 October, while the cabinet was sworn in on 26 October.[240][241]

2023–present

.jpg.webp)

In February 2023, two MPs as well as two members of the City Assembly of Belgrade formerly affiliated with the Serbian Party Oathkeepers defected to SNS, citing their disapproval with their former party's leader.[242] Later that month, another member of the City Assembly of Belgrade defected to SNS, while in March 2023, an MP that was previously a member of the Movement for the Restoration of the Kingdom of Serbia defected to SNS.[243][244] Better Serbia, led by its only MP Dragan Jovanović, merged into SNS in April.[245][246]

A party assembly and a leadership election was held on 27 May.[247][248] Miloš Vučević was elected as Vučić's successor and president of SNS.[249][250] Journalist Ana Lalić characterised the change as "cosmetic".[251] Vučević is a close associate and lawyer of the Vučić family, including Andrej Vučić.[252]

Beginning in September 2022, speculations arose whether Vučić would form a separate political party.[253] Vučić confirmed the formation of the People's Movement for the State (NPZD), a political movement, in March 2023.[254] It was announced that SNS will be a member of the movement,[255] and it will be formalised in September.[256]

Ideology and platform

Political leanings

Following the establishment of SNS, Aleksandar Vučić denounced his previous support for the establishment of Greater Serbia, while Tomislav Nikolić stated that SNS would continue the accession of Serbia to the European Union.[257][258] SNS declared its main tasks to be "fight against corruption and the realisation of the rule of law",[259] while describing itself as a "state-building party".[260] Its white paper (election programme) was published in October 2011.[261]: 189 Jovan Teokarević, an associate professor at the Belgrade Faculty of Political Sciences, described their ideological orientation as a "complete u-turn" in comparison with the Serbian Radical Party (SRS).[262] Bojana Barlovac, a Balkan Insight journalist, stated that SNS "became much closer to DS on its policy profile", although in 2013, she described the party as conservative.[263][264]

SNS has been described as a populist party.[265] Biserko stated that SNS is populist and that it built its ideological image on "social dissatisfaction".[266]: 20–21 Zoran Lutovac, a political scientist and future president of DS, described SNS as populist.[267]: 91 He also added that SNS does not have a "coherent ideology" and that its coalition "includes everyone, regardless of their ideology".[267]: 88 Scholars and political scientists such as Justin Vaïsse and Florian Bieber also agreed that SNS is populist.[268][269] Zoran Stojiljković and Dušan Spasojević, professors at the Belgrade Faculty of Political Sciences, noted that following the formation of SNS, the Serbian political system acquired characteristics of moderate pluralism, and described SNS as a catch-all party.[270]: 448 Additionally, they noted that SNS was formed as a centre-right party,[271]: 115 although its image shifted to the centre after the 2012 elections.[270]: 452 Stojiljković and Spasojević also noted that SNS showed "clear populistic elements",[271]: 115 and that "populist ideas are integral and important for its ideological profile".[271]: 116 Marko Stojić, a Metropolitan University Prague lecturer, also noted that SNS has an eclectic and weekly-rooted ideological profile and that it lacks firm political principles,[272] while he also described SNS as a "typical catch-all party".[273]: 135 Eric Gordy, a professor at the University College London, considers SNS to be a party "based around [Vučić]".[274] Political analyst Ivana Petronijević Terzić has described SNS as clientelistic and said that SNS does not represent any ideology or a category of population.[19] Dušan Milenković, a political consultant, compared SNS to the League of Communists of Yugoslavia (SKJ), however, he added that unlike SKJ, SNS does not express a clear ideology and its policy is rather based on populist measures that span across wide spectrum of political ideologies, from the left to the right.[275]

Ognjen Zorić of Radio Free Europe also described the party as centrist and catch-all, although it noted that "some analysts also stated that the party is right-leaning and conservative".[276] Bieber described SNS centre-right but also as "non-ideological".[277] BBC News noted that SNS "does not have a clear programmatic nor ideological vision", and added that SNS functions as a catch-all party.[278] Bojan Klačar of CeSID stated that SNS "espouses a right-of-centre ideology", but stated that "more importantly, SNS is a catch-all party" that captures a wide variety of opinions, and that SNS can be also considered to be liberal and pro-European.[279][280] Political scientists Đorđe Pavićević and Boban Stojanović, journalist Ivan Radovanović, and authors Aleksandar Marinković and Novak Gajić also described SNS as a catch-all party.[281][282][283] Danas noted that as a catch-all party, SNS has sought to "attract all voters, regardless of ideological commitment" and has flirted with "the most diverse ideologies".[275]

Political scientist Vassilis Petsinis stated that SNS took advantage of fragmentation of centrist and centre-right political parties and that it has consolidated its grip on power by dominating the "continuum that stretches from the liberal centre to the conservative right".[284] Additionally, political scientist Branislav Radeljić, author Laurence Mitchell, and Palgrave Macmillan in their The Statesman's Yearbook had described SNS as centrist,[285][286][287] while George Vasilev, a La Trobe University lecturer, and Srđan Mladenov Jovanović, a scholar, described SNS as centre-right;[288][289] some authors had also described it as a right-wing party.[290][291]

Sociologist Jovo Bakić described SNS as a "pragmatically re-profiled" and moderately conservative party, and compared its development to Gianfranco Fini's projects in Italy.[292] Additionally, he stated that "since its foundation SNS had wanted to remodel itself as a conservative party".[293] Some scholars and journalists also described SNS as conservative,[294] liberal-conservative,[295][296] and national-conservative.[297][298] Stojić said that even though SNS "claimed to belong to the [conservative] family", it is essentially pragmatic and weakly ideologically profiled.[273]: 71

Economy

SNS is economically neoliberal,[273]: 138 [299][300] and it advocates for austerity, market economy reforms, privatisation, reduced spending, and liberalisation of labour laws.[301] Stojiljković and Spasojević noted that SNS already displayed their neoliberal position during the 2012 election period, and that SNS campaigned on significantly reducing subsidies, but also the number of MPs, ministries, agencies, institutes, and the state administration.[271]: 115 Additionally, Stojiljković described its position as "neoliberal populist".[302] While in power, SNS has introduced a law that reformed wages and pensions, which received controversy as wages and pensions were reduced by this law.[278] It has also reformed the labour law, introduced a lex specialis for Belgrade Waterfront, and reformed the law on financial assistance to families and organ donations.[278]

Media and civil liberties

SNS has enacted centralisation policies, especially in Vojvodina.[303]: 14 Since coming to power in 2012, observers have assessed that Serbia has suffered from democratic backsliding into authoritarianism,[304][305] followed by a decline in media freedom and civil liberties.[306][307] A research that was conducted by Cenzolovka in 2015 noted that SNS used media outlets to further their influence.[308] Additionally, SNS was accused of paying internet trolls to praise the government and condemn those who think the opposite on internet forums and social networks.[309] In 2020, Twitter suspended 8,558 accounts that promoted SNS and Vučić, whilst criticising the opposition.[310][311] Meta suspended 5,374 accounts and 12 Facebook groups that were connected to SNS in the fourth quarter of 2022, stating that the "SNS network functioned differently than traditional troll networks".[312] Additionally, Meta revealed that SNS spent over USD$ 150,000 on advertising on Facebook and Instagram.[312] In July 2023, 14,310 Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram accounts that praised the SNS, Vučić, and the government and criticised the opposition were leaked to the public, including their full names and places of origins.[313][314] In response, member of parliament Nebojša Bakarec started a campaign named "Yes, I am a bot",[315] with Vučić later uploading a photo on Instagram titled "Yes, I am too a SNS bot".[316][317]

In 2021, the V-Dem Institute categorised Serbia as an electoral autocracy; the institute also stated that the standards of judiciary and electoral integrity had declined in the past ten years.[318]: 12, 19 According to the Freedom House's report from 2022, SNS has "eroded political rights and civil liberties, put pressure on independent media, the political opposition, and civil society organisations".[319] Additionally, it reported that internet portals close to the government that "manipulate facts and slander independent media" continued to receive public funds on state and local levels.[320] As a response, Vučić and Brnabić criticised Freedom House's report.[321][322]

Foreign policies

Journalists have described SNS as pro-European.[323][324] SNS advocates for close economic and political ties, as well as accession of Serbia to the European Union, alongside "productive ties" with Russia.[325][326] Biserko stated that its support for European Union is rather a "declarative support", and not a substantial one.[261]: 614 Stojić described SNS as "soft Euroenthusiast".[273]: 232 Additionally, Vladimir Goati, a political scientist, described the position of SNS towards the European Union rather as pragmatic, than ideological,[327] while economic anthropologist Jovana Diković described SNS as "euro-pragmatic".[328]

In a 2014 report, Freedom House noted that the SNS-led government advanced Serbia's efforts regarding the European Union.[91]: 544 Dragan Đukanović, a Belgrade Faculty of Political Sciences professor, noted that SNS received support from the U.S. and European Union due to its pro-European agenda.[329] Sonja Biserko, a human rights activist, argued in 2013 that SNS declaratively adopted the agenda of DS and the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) regarding the views on the European Union.[330] Jacobin, an American socialist magazine, described SNS as a fusion of "a nationalist, pro-Russian wing and a modernizing, pro-European wing", while describing Nikolić as being represented in the pro-Russian wing, and Vučić in the pro-European wing, although that the both wings agree on neoliberal austerity.[331]

A European Parliament-published study noted that the SNS-led government continued the "four-pillar policy", a policy that seeks cooperation with European Union, United States, Russia, and China, which was introduced by Boris Tadić, the former president of Serbia and leader of DS.[332] During the 2015 European migrant crisis, the SNS-led government did not impose any restrictions on migrants while crossing into the European Union,[333] which author Vedran Džihić as a pragmatic move.[334] Stojić described the move as "populist-Euroenthusiastic".[273]: 250 SNS supports military neutrality and it opposes joining NATO, although Serbia has continued militarily cooperating with NATO.[325][335][336]

Following the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the government of Serbia led by SNS has condemned the invasion but has not implemented sanctions on Russia.[337][338] In the United Nations, Serbia voted in favour of relations that condemned the invasion of Ukraine.[339][340] Nikola Selaković of SNS has also said that Serbia would not recognise the 2022 annexation referendums in Russian-occupied Ukraine.[341] Vučić has also criticised the Wagner Group and has described Ukraine as Serbia's friend.[342][343]

Demographic characteristics

Political scientist Slaviša Orlović noted in 2011 that supporters of SNS tended to be the unemployed, pensioners, and housewives.[344] According to the Centre for Free Elections and Democracy (CeSID) in 2012, a majority of SNS supporters were male, primary or high school educated, workers', technicians, and dependents, while they had a widespread age structure.[345]: 84–87 In 2014, CeSID reported that its voting base now mostly consisted of people over age of 50, while ideologically speaking, they did not possess any dominant value determination.[346]: 104–106 According to a 2016 opinion poll conducted by Nova srpska politička misao, most of its supporters were over 60 years old, while only 12% of its supporters were highly educated.[347]

Organisation

SNS has a presidency which acts as the operational and political body of the party; it is composed of 30 members.[‡ 1] It also has a main board and an executive board.[‡ 2][‡ 3] The current president of SNS is Miloš Vučević, who was elected in 2023;[250] Jorgovanka Tabaković is the deputy president.[69][223] Aleksandar Šapić, Ana Brnabić, Marko Đurić, Nevena Đurić, Irena Vujović, Siniša Mali, and Vladimir Orlić are the current vice-presidents of SNS; all of them were elected in 2021 and re-elected in 2023, except Vujović, who was not elected in 2021.[223][348] Milenko Jovanov has been the head of the SNS parliamentary group since 2022, while Darko Glišić is the president of the party's executive board.[238][349]

The headquarters of SNS is located at Palmira Toljatija 5/3 in Belgrade.[350] SNS publishes SNS Informator, the party's newspaper.[‡ 4] It also has a youth and women's wing.[‡ 5][351] SNS also operates the For the Serbian People and State Foundation, which it formed in 2019.[352] SNS has received most of its support because of Vučić;[303]: 29 an opinion poll conducted by Faktor Plus in December 2014 noted that 80% of SNS voters would not vote for SNS if someone else than Vučić was the head of the party.[353] With at least 800,000 members as of 2020,[187] SNS is the largest political party in Europe by membership as of 2019.[354]

Petronijević Terzić has stated in 2023 that SNS has used local self-government bodies for party purposes and funds of local public companies for party gatherings, rallies, and promotions.[19] Transparency Serbia has also reported that during the 2016 parliamentary election campaign period SNS has used official events, such as the opening of private factories, to spread their election messages.[355]

International cooperation

In 2011, SNS signed a cooperation agreement with the Freedom Party of Austria.[356] SNS also cooperated with Fidesz, the ruling party of Hungary; Fidesz members attended an SNS rally in 2019.[357] In 2014, it was reported that SNS had ties with the New Serb Democracy in Montenegro,[358] while SNS officials also attended a Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS) rally in 2015.[359] SNS has been accused of "practically running" the Serb List in Kosovo,[360] while Vučić has been also accused of being "figure behind" the party.[361][362]

SNS representatives in the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) joined the European People's Party (EPP) in 2013.[363] In the same year, SNS received support from the Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU) due to the establishment of the Brussels Agreement.[303]: 38 SNS has received support from the CDU in regards to membership in the EPP in 2015.[364] A year later, SNS and its youth wing became associate members of EPP.[365][366] SNS officials attended CDU's congress in 2018.[367] SNS became a member of the International Democrat Union in 2018.[368] In the PACE, SNS was also affiliated with the Free Democrats Group; Dubravka Filipovski once served as its vice-chairperson.[369]

SNS took part in a meeting with Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officials in 2019.[370] At the meeting, the parties "pledged to forge ever-closer links".[371] SNS officials were also present in a 2021 summit that was organised by CCP, while in 2023 SNS described CCP as its inspiration.[372][373] SNS established connections with United Russia (YeR) in 2010.[374] Tomislav Nikolić was present at a YeR congress in 2011, while a year later, SNS officials were present at a YeR conference.[375][376] Since then, SNS and YeR have signed several cooperation agreements,[377][378] most recently being in 2021.[379]

List of presidents

| # | President | Birth–Death | Term start | Term end | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tomislav Nikolić | .jpg.webp) | 1952– | 21 October 2008 | 24 May 2012 | |

| 2 | Aleksandar Vučić | .jpg.webp) | 1970– | 24 May 2012 | 27 May 2023 | |

| 3 | Miloš Vučević | .jpg.webp) | 1974– | 27 May 2023 | Incumbent | |

Electoral performance

Parliamentary elections

| Year | Leader | Popular vote | % of popular vote | # | # of seats | Seat change | Coalition | Status | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | Tomislav Nikolić | 940,659 | 25.16% | 58 / 250 |

PS | Government | [380] | ||

| 2014 | Aleksandar Vučić | 1,736,920 | 49.96% | 128 / 250 |

BKV | Government | [381] | ||

| 2016 | 1,823,147 | 49.71% | 93 / 250 |

SP | Government | [382] | |||

| 2020 | 1,953,998 | 63.02% | 157 / 250 |

ZND | Government | [383] | |||

| 2022 | 1,635,101 | 44.27% | 95 / 250 |

ZMS | Government | [384] |

Presidential elections

| Year | Candidate | 1st round popular vote | % of popular vote | 2nd round popular vote | % of popular vote | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | Tomislav Nikolić | 2nd | 979,216 | 26.22% | 1st | 1,552,063 | 51.16% | [380] |

| 2017 | Aleksandar Vučić | 1st | 2,012,788 | 56.01% | — | — | — | [385] |

| 2022 | 1st | 2,224,914 | 60.01% | — | — | — | [386] | |

Provincial elections

| Year | Leader | Popular vote | % of popular vote | # | # of seats | Seat change | Coalition | Status | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | Igor Mirović | 185,311 | 19.26% | 22 / 120 |

PV | Opposition | [387] | ||

| 2016 | 428,452 | 45.78% | 63 / 120 |

SP | Government | [388] | |||

| 2020 | 498,495 | 61.58% | 65 / 120 |

ZND | Government | [389] |

Belgrade City Assembly elections

| Year | Leader | Popular vote | % of popular vote | # | # of seats | Seat change | Coalition | Status | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | Tomislav Nikolić | 219,198 | 26.83% | 37 / 110 |

PS | Opposition | [390] | ||

| 2014 | Aleksandar Vučić | 351,183 | 43.62% | 63 / 110 |

BKV | Government | [391] | ||

| 2018 | 366,461 | 44.99% | 64 / 110 |

ZSVB | Government | [392] | |||

| 2022 | 348,345 | 38.83% | 36 / 110 |

ZMS | Government | [393] |

References

- Gorup, Radmila (2013). After Yugoslavia: The Cultural Spaces of a Vanished Land. Stanford University Press. p. 72. ISBN 9780804787345.

- Pavlović, Dušan (2 July 2009). "DS i SNS – borba za srednjeg glasača" [DS and SNS – the fight for the average voter]. Politika (in Serbian). Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- "Serb opposition leader resigns". BBC News. 7 September 2008. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- Kojić, Nikola (12 August 2023). "Najveće podele u partijama od 1990: Skoro da nema stranke koja se nije pocepala" [The biggest divisions in parties since 1990: There is almost no party that has not split]. N1 (in Serbian). Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- "Nikolić oformio poslanički klub" [Nikolić forms a parliamentary group]. B92 (in Serbian). 8 September 2008. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- Maksimović, Marina (9 September 2008). "Toma podelio stranku" [Toma splits the party]. Deutsche Welle (in Serbian). Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- "Tomislav Nikolić: Ono što je bila SRS više ne postoji" [Tomislav Nikolić: What was SRS it no longer exists]. Radio Television of Serbia (in Serbian). 8 September 2008. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- "Nikolić osniva novu stranku" [Nikolić to form a new party]. Radio Television of Serbia (in Serbian). 11 September 2008. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- "Nikolić i Vučić osnivaju stranku?" [Nikolić and Vučić are founding a party?]. Radio Slobodna Evropa (in Serbian). 14 September 2008. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- "Nikolić nije više u SRS-u" [Nikolić is no longer in SRS]. B92 (in Serbian). 12 September 2008. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- "Zbogom SRS" [Goodbye SRS]. Deutsche Welle (in Serbian). 13 September 2008. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- "Nikolić party to be called "Serb Progressive"". B92 (in Serbian). 14 September 2008. Archived from the original on 28 September 2008. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- "Nikolić osniva naprednu stranku" [Nikolić to form a progressive party]. Mondo (in Serbian). 24 September 2008. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- "Nikolić: Službeno osnovana Srpska napredna stranka" [Nikolić: The Serbian Progressive Party has been officially founded]. Radio Slobodna Evropa (in Serbian). 10 October 2008. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- "Nikolić party holds founding congress". B92. 22 October 2008. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- Zoran Stojiljković; Jelena Lončar; Dušan Spasojević (2012). Političke stranke i zakonodavna aktivnost Narodne skupštine Republike Srbije: studije u okviru projekta: jačanje odgovornosti Narodne skupštine Republike Srbije [Political parties and legislative activity of the National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia: studies within the project: strengthening the responsibility of the National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia]. Beograd: Fakultet političkih nauka, Centar za demokratiju. p. 36. ISBN 978-86-84031-53-4. OCLC 808939935.

- "Nikolić: Poslanički klub "Napred Srbijo" ima 20 članova" [Nikolić: The parliamentary group "Forward Serbia" has 20 members]. Radio Television of Vojvodina (in Serbian). 26 September 2022. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- "Nikolićeva stranka: Do 21. oktobra sve spremno" [Nikolić's party: By 21 October, everything will be ready]. Radio Television of Vojvodina (in Serbian). 21 September 2008. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- Petronijević Terzić, Ivana (28 July 2023). "Ko je ko u vladajućoj koaliciji" [Who is who in the ruling coalition]. Demostat (in Serbian). Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- "Vučić: Parlamentarni izbori do oktobra 2009 godine" [Vučić: Parliamentary elections until October 2009]. Radio Television of Vojvodina (in Serbian). 11 November 2008. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- "Jovanović i Vučić za izbore 2009" [Jovanović and Vučić in favour of elections to be held in 2009]. Blic (in Serbian). 17 December 2008. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- "SNS će biti opozicija" [SNS will be the opposition]. Radio Television of Serbia (in Serbian). 25 November 2008. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- "SNS: Inicijativa za promenu Ustava neozbiljna" [SNS: The initiative to change the Constitution is not serious]. Radio Television of Vojvodina (in Serbian). 10 May 2009. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- "Konačni rezultati u Zemunu" [Final results in Zemun]. Radio Television of Serbia (in Serbian). 11 June 2009. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- Džihić, Vedran; Kramer, Helmut (2009). Kosovo After Independence: Is the EU's EULEX Mission Delivering on its Promises? (PDF). Berlin: Friedrich Ebert Foundation. p. 5. ISBN 978-3-86872-152-2.

- Didanović, Vera (10 December 2009). "Naprednjaci napred, demokrate stoj" [Progressives going forward, democrats stagnant]. Vreme (in Serbian). Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- "SNS pobedila na Voždovcu - četiri liste prešle cenzus" [SNS won in Voždovac - four lists crossed the threshold]. Radio Television of Vojvodina (in Serbian). 7 December 2009. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- "Voždovac: SNS pobedio, G17+ ispod cenzusa!" [Voždovac: SNS won, G17+ below the threshold!]. Deutsche Welle (in Serbian). 7 December 2009. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- "Naprednjaci formiraju vlast na Voždovcu" [Progressives form the government in Voždovac]. Radio Television of Serbia (in Serbian). 15 December 2009. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- Borba protiv korupcije: između norme i prakse [The fight against corruption: between the norm and practice] (PDF) (in Serbian). CeSID. 2016. p. 8.

- "SNS: Više od pola miliona potpisa" [SNS: More than half a million signatures]. Radio Television of Serbia (in Serbian). 15 December 2010. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- "SNS: Sve više razloga za izbore" [SNS: More and more reasons for elections]. Radio Television of Serbia (in Serbian). 28 March 2010. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- "SNS: Vlada stvara novu krizu" [SNS: The government is creating a new crisis]. Radio Television of Serbia (in Serbian). 14 March 2010. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- "Beogradski SNS najavljuje demonstracije" [Belgrade branch of SNS announces demonstratons]. Radio Television of Vojvodina (in Serbian). 25 March 2010. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- Cvetković, Ljudmila; Martinović, Iva (30 March 2010). "Skupština Srbije usvojila Deklaraciju o Srebrenici" [The Serbian Parliament adopts the Declaration on Srebrenica]. Radio Slobodna Evropa (in Serbian). Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- "Usvojena Deklaracija o Srebrenici" [The Srebrenica Declaration has been adopted]. Radio Television of Serbia (in Serbian). 30 March 2010. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- "Naprednjaci najavili miting za 4. februar u Beogradu" [Progressives announce a rally for 4 February in Belgrade]. Danas (in Serbian). 24 December 2010. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- "SNS najavila miting za 4. februar" [SNS announces a rally for 4 February]. Radio Television of Vojvodina (in Serbian). 24 December 2010. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- "SNS predao potpise za izmenu Ustava" [SNS submitted signatures for amending the Constitution]. B92 (in Serbian). 13 January 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- Vasović, Aleksandar (5 February 2011). "Serbia holds biggest opposition protest in years". Reuters. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- "Serbian opposition rally calls for early elections". Deutsche Welle. 2 February 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- "SNS i NS: Protesti do ispunjenja" [SNS and NS: Protests until fulfillment of demands]. B92 (in Serbian). 1 February 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- "SNS: Izbori ili protesti" [SNS: Elections or protests]. B92 (in Serbian). 5 February 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- "Novi rok SNS-a" [New deadline of SNS]. Radio Television of Serbia (in Serbian). 10 April 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- "Protest ispred Predsedništva Srbije" [Protests in front of the Presidency of Serbia]. B92 (in Serbian). 19 April 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- "SNS: Tadićev režim u histeriji" [SNS: Tadić's regime in hysteria]. B92 (in Serbian). 7 April 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- "Miting SNS u Nišu" [SNS meeting in Niš]. Južne vesti (in Serbian). 28 October 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- "Nikolić stabilan, izbori cilj" [Nikolić is stable, elections are the goal]. Nezavisne novine (in Serbian). 17 April 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- "Opozicija se okuplja oko Srpske napredne stranke" [Opposition is gathering around the Serbian Progressive Party]. Boom93 (in Serbian). 16 November 2010. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- "Miting opozicije u Beogradu" [Opposition rally in Belgrade]. Radio Television of Republika Srpska (in Serbian). 5 February 2011. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- Mrdić, Uglješa (15 April 2011). "Tomislav Nikolić: Posle izbora moguća je samo proevropska vlada" [Tomislav Nikolić: After the elections, only a pro-European government is possible]. Pečat (in Serbian). Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- Kojić, Nikola (5 June 2020). "Izbori 2012: Poraz Tadića i DS, Dačićev preokret i dolazak SNS na vlast" [2012 elections: Defeat of Tadić and DS, Dačić's turnaround and SNS coming to power]. N1 (in Serbian). Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- Milovanović, Bojana (8 August 2011). "Parties jockey for support well ahead of Serbia's elections". Southeast European Times. Archived from the original on 17 October 2011. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- "Report: Elections to be held in spring 2012". B92. 29 June 2011. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- "Raspisani parlamentarni izbori" [Parliamentary election announced]. Radio Television of Serbia (in Serbian). 13 March 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- "NS: Nikolić nosilac liste SNS-NS-PSS-PS" [NS: Nikolić, the representative of the SNS-NS-PSS-PS list]. Mondo (in Serbian). 22 January 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- "Ko su kandidati za poslanike" [Who are the candidates for deputies?]. Vreme (in Serbian). 22 March 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- "Proglašena izborna lista SNS" [SNS election list announced]. B92 (in Serbian). 20 March 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- "Tomislav Nikolić kandidat SNS za predsednika" [Tomislav Nikolić is the presidential candidate of SNS]. Blic (in Serbian). 5 April 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- "Jorgovanka Tabaković kandidatkinja SNS za premijerku Srbije" [Jorgovanka Tabaković is the SNS candidate for prime minister of Serbia]. Blic (in Serbian). 26 April 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- Stilin, Bojan (20 April 2012). "Rudy Giuliani došao u Srbiju podržati Tomu Nikolića" [Rudy Giuliani came to Serbia to support Toma Nikolić]. tportal (in Croatian). Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- Kirchick, James (24 May 2012). "Rudy Giuliani Hits a New Low: Consulting for Serbian Nationalists". Tablet Magazine. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- "SNS najjači u Skupštini, Nikolić i Tadić u drugom krugu, Đilas vodi u Beogradu" [SNS the strongest in the Assembly, Nikolić and Tadić in the second round, Đilas leads in Belgrade]. Radio Slobodna Evropa (in Serbian). 6 May 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- "RIK: Rezultati parlamentarnih izbora na osnovu 97,51 odsto biračkih mesta" [RIK: Results of the parliamentary election based on 97.51 percent of polling stations]. eizbori (in Serbian). 7 May 2012. Archived from the original on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- "Konačni rezultati predsedničkih izbora" [Final results of the presidential election]. Radio Television of Serbia (in Serbian). 2 September 2022. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- "Konačni rezultati pokrajinskih izbora" [Final results of the provincial elections]. Radio Television of Serbia (in Serbian). 2 September 2022. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- "Konačni rezultati za Beograd" [Final results for Belgrade]. Radio Television of Serbia (in Serbian). 2 September 2022. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- "Nikolić podneo ostavku i zaplakao" [Nikolić resigned and cried]. B92 (in Serbian). 24 May 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- "Progressives elect new leader, deputy leader". B92. 29 September 2012. Archived from the original on 4 February 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- "Nikolić počeo konsultacije o vladi sa SPS-PUPS-JS" [Nikolić starts government consultations with SPS-PUPS-JS]. Nezavisne novine (in Serbian). 11 June 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- "Sve izvesnija koalicija SNS-SPS" [A SNS-SPS coalition is increasingly more certain]. B92 (in Serbian). 26 June 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- "Nova vlada položila zakletvu" [The new government has been sworn in]. B92 (in Serbian). 27 July 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- Petrović, Vesna; Joksimović, Vladan (2013). Ljudska prava u Srbiji: pravo, praksa i međunarodni standardi ljudskih prava [Human rights in Serbia: law, practice, and international human rights standards] (PDF) (in Serbian). Belgrade: Beogradski centar za ljudska prava. p. 244. ISBN 978-86-7202-141-7.

- "Srbija ima novu vladu" [Serbia has a new government]. Deutsche Welle (in Serbian). 27 July 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- "Sastav Dačićevog kabineta" [Composition of Dačić's cabinet]. Radio Television of Serbia (in Serbian). 27 July 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- Gligorijević, Jovana (31 October 2012). "Udario junak na junaka" [A hero hit on a hero]. Vreme (in Serbian). Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- Barlovac, Bojana (12 December 2012). "Serbian Police Arrest Miroslav Miskovic". Balkan Insight. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- Vasović, Aleksandar (12 December 2012). "Police arrest Serbia's richest man in anti-graft probe". Reuters. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- "Serbia Tycoon Miskovic Pays 12 Million Euro Bail". Balkan Insight. 22 July 2013. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- Cvejić, Bojan (21 January 2013). "SNS najmasovnija, DS napustilo 3.000 članova" [SNS is the largest, DS has lost 3,000 members]. Danas (in Serbian). Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- "Maja Gojković: Narodna partija kolektivno prešla u SNS" [Maja Gojković: The People's Party collectively joined SNS]. Blic (in Serbian). 3 December 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- "SNS na istorijskom maksimumu - 41%" [SNS at historical maximum - 41%]. B92 (in Serbian). 27 February 2013. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- "Rekonstrukcija vlade Vučiću se obila o glavu?" [Did the reconstruction of the government backfire on Vučić?]. Deutsche Welle (in Serbian). 31 July 2013. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Vasović, Aleksandar (14 August 2013). "McKinsey consultant Krstic to be Serbian finance minister". Reuters. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- "Jedanaest novih ministara" [Eleven new ministers]. Politika (in Serbian). 29 August 2013. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- "Zoran Babić šef poslaničke grupe SNS" [Zoran Babić is now the head of the SNS parliamentary group]. Kurir (in Serbian). 27 August 2013. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- "Belgrade Mayor Dragan Đilas dismissed". European Forum. 24 September 2013. Archived from the original on 3 September 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- De Launey, Guy (24 January 2014). "Serbia transforming from pariah to EU partner". BBC News. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Žarković, Dragoljub (13 November 2013). "Tužni tok ministarkine karijere – Ko je sklonio Zoranu Mihajlović da se Aleksej Miler ne bi iznervirao?" [The sad course of the minister's career - Who protected Zorana Mihajlović so that Aleksej Miler would not get annoyed?]. Vreme (in Serbian). Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Pavlović, Koča (23 March 2014). "Living the Serbian dream: a look at Aleksandar Vučić's election victory". openDemocracy. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- Savić, Miša (2014). "Serbia" (PDF). Freedom House. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- Gligorijević, Jovana (29 January 2014). "Tamo gde je sve po mom" [Where everything is my way]. Vreme (in Serbian). Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- "Neću da budem premijer bez izbora" [I will not be the prime minister without an election]. B92 (in Serbian). 26 January 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- "Nek su nam srećni novi izbori" [Good luck with the new elections]. B92.net (in Serbian). 29 January 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- "SNS predstavila izbornu listu" [SNS presented its electoral list]. Nezavisne novine (in Serbian). 4 February 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- Vasiljević, P. (3 February 2014). "Vučić: Bićemo uvek uz narod" [Vučić: We will always be with the people]. Novosti (in Serbian). Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- "Programi ili parole" [Programmes or slogans]. Deutsche Welle (in Serbian). 1 March 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- Pavković, Aleksandar (2 April 2014). "Serbian election: after a landslide victory, is EU accession next?". The Conversation. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- Savić, Miša (2015). "Serbia". Freedom House. Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- Kojić, Nikola (11 June 2020). "Izbori 2014: Najniža izlaznost u istoriji, ubedljiva pobeda SNS, Vučić premijer" [2014 elections: Lowest turnout in history, convincing victory of SNS, Vučić becomes prime minister]. N1 (in Serbian). Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- "Konačni rezultati izbora za Beograd" [Final election results for Belgrade]. Radio Television of Serbia (in Serbian). 17 March 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- "Siniša Mali gradonačelnik Beograda" [Siniša Mali becomes mayor of Belgrade]. Nezavisne novine (in Serbian). 24 April 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- "Serbia swears in new prime minister". Deutsche Welle. 27 April 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- "Srbija ima novu vladu" [Serbia has a new government]. Deutsche Welle (in Serbian). 28 April 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- Prevremeni parlamentarni izbori 24. april 2016 [Early parliamentary elections on 24 April 2016] (PDF) (in Serbian). Warsaw: Kancelarija za demokratske institucije i ljudska prava. 2016.

- "The 2014 CSO Sustainability Index for Central and Eastern Europe and Eurasia" (PDF). United States Agency for International Development. 2014. p. 195. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- "Serbia election: Pro-EU Prime Minister Vucic claims victory". BBC News. 24 April 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- "Naprednjaci srušili Stevanovića: Nikolić na čelu Kragujevca" [Progressive overthrow Stevanović: Nikolić as the head of Kragujevac]. N1 (in Serbian). 28 October 2014. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- Gligorijević, Jovana (5 November 2014). "Prvi sin u svom gradu" [The first son in his town]. Vreme (in Serbian). Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- Femić, Ratko (31 January 2015). "Srbija, država partijskih knjižica" [Serbia, the country of party booklets]. Al Jazeera (in Bosnian). Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- Ćetković, Kristina (26 April 2015). "Protest zbog potpisivanja ugovora "Beograd na vodi"" [Protests due to the signing of the Belgrade Waterfront contract]. Analitika (in Serbian). Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- "Potpisan ugovor o Beogradu na vodi" [An agreement on the Belgrade Waterfront has been signed]. Vreme (in Serbian). 30 April 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- Mihajlović, Branka (21 September 2015). "Ugovor o Beogradu na vodi otkriva veliku prevaru" [The Belgrade Waterfront agreement reveals a big fraud]. Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- Rudić, Mirko (8 April 2015). "Ko nam nudi patku" [Who is offering us a duck?]. Vreme (in Serbian). Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- Nešić, Milan (17 February 2014). "Beograd na vodi: Predizborni trik ili realnost" [Belgrade Waterfront: Pre-election trick or reality]. Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- "Protesti zbog projekta "Beograd na vodi"" [Protests due to the Belgrade Waterfront project]. Radio Television of Serbia (in Serbian). 27 September 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- Nešić, Milan (24 December 2015). "Protest paora ispred Skupštine Srbije: Čija je naša zemlja?" [Farmers protest in front of the Serbian Parliament: Whose country is ours?]. Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- Damnjanović, Miloš (2016). "Serbia". Freedom House. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- Petrović, Ivica (18 January 2016). "Zašto su raspisani izbori u Srbiji?" [Why were elections announced in Serbia?]. Deutsche Welle (in Serbian). Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- Bojić, Saša (19 January 2016). "Izbori – može mu se" [Elections - he can do it]. Deutsche Welle (in Serbian). Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- Macdowall, Andrew (19 January 2016). "Serb election likely to result in government romp". Politico. Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- Nikitović, Vladimir (26 February 2016). "SNS kampanja od vrata do vrata: Da li glasaš za nas ili ne?" [SNS door-to-door campaign: Will you vote for us or not?]. Radio Slobodna Evropa (in Serbian). Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- "Nikolić raspisao izbore: Želim da pobedi SNS" [Nikolić calls the elections: I want SNS to win]. B92 (in Serbian). 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- Stojanović, Boban; Casal Bértoa, Fernando (22 April 2016). "There are 4 reasons countries dissolve their parliaments. Here's why Serbia did". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- "Proglašena prva lista - "Aleksandar Vučić - Srbija pobeđuje"" [First list announced - Aleksandar Vučić - Serbia is Winning]. Radio Television of Serbia (in Serbian). 6 March 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- "Kandidati za poslanike 2016: Lista Aleksandar Vučić – Srbija pobeđuje" [Candidates for MPs 2016: Aleksandar Vučić - Serbia is Winning list]. Vreme (in Serbian). 10 March 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- Milenković, M. R. (3 March 2016). "Martinović budući šef poslaničke grupe?" [Martinović the future head of the parliamentary group?]. Danas (in Serbian). Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- Glavonjić, Zoran (19 April 2016). "Gde ko stoji: Ključni stavovi pred izbore" [Who stands where: Key attitudes before the elections]. Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- "Izborni rezultat 2016" [2016 election results]. Vreme (in Serbian). 28 April 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- "Izbori Vojvodina 2016: SNS dobio većinu od 120 mandata" [2016 Vojvodina elections: SNS won a majority of 120 mandates]. 021.rs (in Serbian). 26 April 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- Stavljanin, Dragan (28 April 2016). "Serbian Elections: The Ghost of Milosevic Haunts Serbia's European Path". Radio Free Europe. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- "Lideri četiri opozicione stranke podnose krivične prijave protiv Pošta Srbije" [Leaders of four opposition parties file criminal charges against Post of Serbia]. Nova Ekonomija (in Serbian). 28 April 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- "Srbija: Protest opozicije zbog sumnje u izbornu krađu" [Serbia: Protest by the opposition due to suspected election theft]. Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). 30 April 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- "Čiji je Beograd: drugi protest, dvaput više ljudi na ulicama" [Whose is Belgrade: second protest, twice as many people on the streets]. Vice (in Serbian). 25 May 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- Zorić, Jelena (3 June 2016). "Ne davimo Beograd: Ko su i ko ih finansira" [Do not let Belgrade d(r)own: who are they and who finances them]. N1 (in Serbian). Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- Veselinović, Stefan (21 October 2016). "Posle 15 godina muzika je opet deo jednog građanskog protesta" [After 15 years, music is again part of a civil protest]. Vice (in Serbian). Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- Zorić, Ognjen (28 May 2016). "Skupština SNS izabrala novo rukovodstvo" [SNS assembly elects new leadership]. Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- Šinković, Norbert (20 June 2016). "Mirović novi predsednik Pokrajinske vlade" [Mirović is the new president of the Provincial Government]. Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- Nasaković, Đorđe (8 August 2016). "Objavljen sastav nove Vlade" [The composition of the new government has been announced]. N1 (in Serbian). Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- "New Serbian government gets parliament approval". Reuters. 11 August 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- Pantović, Milivoje (10 August 2016). "New Serbian Cabinet is Mix of Old and New". Balkan Insight. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- "Vučić: Nikolić je imao dobre rezultate" [Vučić: Nikolić had good results]. N1 (in Serbian). 27 December 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- "Nikolić: Iznenadila bi me kandidatura Vučića" [Nikolić: I would be surprised by Vučić's candidacy]. Radio Television of Serbia (in Serbian). 6 January 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- "Vulin: Građani žele Vučićevu kandidaturu" [Vulin: Citizens want Vučić's candidacy]. Radio Television of Serbia (in Serbian). 1 January 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- "Mihajlović: Glasam da Vučić bude kandidat SNS-a za predsednika" [Mihajlović: I vote for Vučić to be the SNS candidate for president]. Radio Television of Serbia (in Serbian). 6 January 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- Živanović, Maja (15 February 2017). "PM Aleksandar Vucic to Run for Serbian Presidency". Balkan Insight. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- "Kandidature za predsedničke izbore" [Candidates for the presidential election]. Vreme (in Serbian). 4 March 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- Nenadović, Aleksandra (31 March 2017). "Major Serbian Newspapers Print Ruling Party Campaign Posters". Voice of America. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- Filipović, Gordana (28 March 2017). "How a Premier May Become a Strongman in Serbia". Bloomberg. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- Crosby, Alan (31 March 2017). "Vucic's Bid To Cement Power In Serbia Raises Concerns Ahead Of Presidential Vote". Radio Free Europe. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- "Zvanični rezultati predsedničkih izbora 2017" [Official results of the 2017 presidential election]. Vreme (in Serbian). 21 April 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- da Silva, Chantal (8 April 2017). "Media 'turning blind eye' to Serbian anti-corruption rallies". The Independent. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- Živanović, Maja (10 April 2017). "Serbia Protests: Thousands Demand Vucic's Resignation". Balkan Insight. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- Crosby, Alan; Martinović, Iva (17 April 2017). "Whistles And Passports: Serbia's Young Protesters Take On 'The System'". Radio Free Europe. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- "Svetski mediji o inauguraciji Vučića" [International media about the inauguration of Vučić]. N1 (in Serbian). 31 May 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- Petrović, Ivica (22 June 2017). "Lažna drama u Srbiji oko Brnabićke" [Fake drama in Serbia about Brnabić]. Deutsche Welle (in Croatian). Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- "Serbian Lawmakers, In Historic First, Elect Openly Gay, Female Prime Minister". Radio Free Europe. 30 June 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- "Serbian President Discusses Borders, Trade With Bosnian Leaders". Radio Free Europe. 7 September 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- Petrović, Vesna (2018). Ljudska prava u Srbiji 2017: Pravo, praksa i međunarodni standardi ljudskih prava [Human rights in Serbia in 2017: Law, practice, and international human rights standards] (in Serbian). Belgrade: Beogradski centar za ljudska prava. ISBN 978-86-7202-188-2.

- Panović, Zoran (16 October 2017). "Sto pedeset godina "Kapitala" Karla Marksa" [One hundred and fifty years of "Das Kapital" by Karl Marx]. Demostat (in Serbian). Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- "SNS predala listu za izbore u Beogradu" [SNS submitted its list for the elections in Belgrade]. N1 (in Serbian). 15 January 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- "Ko je u prvih 20 na listi SNS za Beograd" [Who is in the top 20 on the SNS list for Belgrade]. Radio Television of Serbia (in Serbian). 14 January 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- "SNS predstavio kandidate za odbornike i program za bolji i lepši Beograd" [SNS presents the candidates for councilors and the programme for a better and more beautiful Belgrade]. Novinska agencija Beta (in Serbian). 5 February 2018. Archived from the original on 23 September 2022. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- "Konačni rezultati beogradskih izbora 2018" [Final results of the 2018 Belgrade election]. N1 (in Serbian). 5 March 2018. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- Beogradski izbori 2018: finalni izveštaj CRTA posmatračke misije [2018 Belgrade elections: final report of the CRTA observation mission] (PDF) (in Serbian). Belgrade: CRTA. 2018. p. 59.

- "Zvanično - Zoran Radojičić novi gradonačelnik Beograda" [It is official - Zoran Radojičić is the new mayor of Belgrade]. B92 (in Serbian). 7 June 2018. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- Petrović, Ivica (13 July 2018). "Vlast u Srbiji – neupitni autoritet" [Government in Serbia - unquestionable authority]. Deutsche Welle (in Bosnian). Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- "Thousands protest in Serbia over attack on opposition politician". Reuters. 8 December 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- "Serbia: thousands rally in fourth week of anti-government protests". The Guardian. 30 December 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- "Serbia Leader Announces Arrest of Mayor Over Attack on Journalist". Voice of America. 25 January 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- "More than 10,000 protest in Belgrade against Serbian president". Reuters. 19 January 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- Miladinović, Aleksandar (17 January 2019). "Pet stvari koje su obeležile "Putindan" u Beogradu" [Five things that marked "Putin Day" in Belgrade]. BBC News (in Serbian). Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- Marković, Tomislav (3 February 2019). "Srpska napredna stranka, kula od članskih karata" [Serbian Progressive Party, a tower of membership cards]. Al Jazeera (in Bosnian). Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- ""Budućnost Srbije" na jugu" ["Future of Serbia" in the south]. Radio Television of Serbia (in Serbian). 7 February 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- "Nadežda Gaće o Vučićevoj kampanji Budućnost Srbije" [Nadežda Gaće on Vučić's Future of Serbia campaign]. N1 (in Serbian). 8 February 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- Georgiev, Slobodan (24 April 2019). "Vucic Rally May Have Silenced Serbia's Protest Movement". Balkan Insight. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- "PM Brnabic joins Vucic's ruling Serbian Progressive Party". N1 (in Serbian). 10 October 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- Petrović, Ivica (12 January 2020). "Cenzus od tri odsto – makijavelistički potez?" [The three percent threshold - a Machiavellian move?]. Deutsche Welle (in Serbian). Belgrade. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- Pujkilović, Milica (18 February 2020). "Zagrevanje za kampanju – slogan SNS-a i rasprava o bojkotu" [Warming up for the campaign - SNS slogan and discussion of the boycott]. Radio Television of Serbia (in Serbian). Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- "Srpska napredna stranka prva predala listu za izbore" [The Serbian Progressive Party was the first to submit a list for the election]. Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). 5 March 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- "Serbia postpones April 26 elections due to coronavirus outbreak - state election commission". Reuters. 16 March 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- "Serbia to hold general election despite pandemic". Associated Press. 4 May 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- "Srbija: Obustava protesta subotom dok se ne popravi epidemiološka situacija" [Serbia: Suspension of protests on Saturday until the epidemiological situation improves]. Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). 10 March 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- "Serbia calls election; opposition to boycott". Al Jazeera. 4 March 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- "Učvršćivanje Vučićeve dominacije". Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). 22 June 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- Božić Krainčanić, Svetlana (6 May 2020). "Fridom Haus: Srbija i Crna Gora više nisu u kategoriji demokratija" [Freedom House: Serbia and Montenegro are no longer in the category of democracies]. Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- Lazarević, Milan (18 June 2020). "Kako se zaposliti bez članstva u SNS" [How to get a job without membership in SNS]. Danas (in Serbian). Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- "RIK objavio konačne rezultate parlamentarnih izbora, izlaznost oko 49 odsto" [RIK announces the final results of the parliamentary election, turnout is around 49 percent]. Danas (in Serbian). 5 July 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2022.