Genevieve

Genevieve (French: Sainte Geneviève; Latin: Sancta Genovefa, Genoveva; also called Genovefa[1] and Genofeva;[2] c. 419/422 AD – 502/512 AD) is the patroness saint of Paris in the Catholic and Orthodox traditions. Her feast is on 3 January.

Genevieve | |

|---|---|

Saint Genevieve, seventeenth-century painting, Musée Carnavalet, Paris | |

| Virgin | |

| Born | c. 419–422 Nanterre, Western Roman Empire |

| Died | 502–512 (aged 79–93) Paris, Francia |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church Orthodox Church |

| Canonized | Pre-congregation |

| Feast | 3 January |

| Attributes | Lit candle, breviary, angels and demons, liturgical vessel, crown, keys of the city of Paris |

| Patronage | Paris |

Genevieve was born in Nanterre. After encountering Germanus of Auxerre and Lupus of Troyes, she moved to Paris (then known as Lutetia) and dedicated herself to a Christian life.[3] In 451 she led a "prayer marathon"[4] that was said to have saved Paris by diverting Attila's Huns away from the city. When the Germanic king Childeric I besieged the city in 464, Genevieve acted as an intermediary between the city and its besiegers, collecting food and convincing Childeric to release his prisoners.[3]

Life

Genevieve was born in c. 419 or 422 in Nanterre, France, almost seven kilometers from Paris, to her father, Severus, and her mother, Gerontia.[5] Genevieve appears in the Martyrology of Jerome; her vita appeared many centuries after her death,[2] although hagiographer Donald Attwater states that the vita claims to be written by a contemporary of Genevieve and "Its authenticity and value are the subject of much discussion".[6] As David Farmer states, "little can be known about her with certainty, but her cult has flourished on civil and national pride".[2]

Even though popular tradition represents Genevieve's parents as poor peasants,[5] their names, which were common amongst the Gallo-Roman aristocracy, are considered evidence that she was born into the Gallic upper class. It is more likely that Genevieve was born among the Gallic upper class. She was recognised for her religious devotion from an early age.[7][6]

On their way to Britain from Gaul to put an end to the Pelagian heresy around 429, Germanus of Auxerre and Lupus of Troyes stopped at Nanterre.[1] Germanus noticed Genevieve's pious behavior and thoughtfulness in a crowd of villagers who gathered to meet and obtain Germanus' and Lupus' blessing, and after speaking to her and encouraging "her to persevere in the path of virtue",[5] interviewed her parents and told them that she would, be great before the face of the Lord"[8] and that by her example, lead and teach many consecrated virgins.[5][8] Genevieve "confided to him that she wanted to live only for God";[9] according to her vita, Germanus confirmed her desire to become a consecrated virgin, and plucking a coin from the ground, directed her to have a necklace made from it to remind her about their meeting.[10] According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, Germanus gave her a medal engraved with a cross and instructed her to wear it instead of pearls and gold jewelry to help her remember her commitment to Christ.[5] The Catholic Encyclopedia also states that since there were no convents near her home, she "remained at home, leading an innocent, prayerful life".[5] Her vita reports that she was inspired by Germanus, who David Farmer describes as Genevieve's supporter,[2] to dedicate her life and virginity to God's service, which was not limited to an established rule or a monastic lifestyle.[3]

It is unknown when Genevieve formally became a consecrated virgin; some sources state that she received her veil from St. Gregory, while others state that she, along with two companions, received them from the Bishop of Paris when she was 15 years old.[2][5][9] Genevieve's vita relates a story about her mother being struck blind after violently preventing Genevieve from attending church on a feast day. After almost two years Genevieve realised that she was the reason for her mother's blindness; after her mother asked her to retrieve water for her from a nearby well, she restored her mother's sight with it. Later, she was brought with two girls before a bishop to be consecrated as virgins, but he blessed her before the other girls even though she was the youngest.[11]

After her parents' deaths, Genevieve went to live with her godmother in Paris, devoting herself to prayer and charitable works. She was stricken with severe paralysis and almost died; after she recovered, she reported that she had seen visions of heaven.[2][12][9] In Paris, the young woman became admired for her piety and devotion to works of charity, and practiced fasting, "severe corporal austerities",[5] and the mortification of the flesh, which included abstaining from meat and breaking her fast only twice a week. She fasted, between the ages of 15 to 50, from Sunday to Thursday and from Thursday to Sunday; her diet consisted of beans and barley bread and she never drank alcohol. After she turned 50 and by order of her bishops, she added fish and milk to her diet.[5][13] She devoutly kept vigil each Saturday night, "following the teaching of the Lord concerning the servant who awaited the master's return from a wedding".[14]

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, her neighbours, "filled with jealousy and envy",[5] accused Genevieve of being a hypocrite and imposter and that her visions and prophecies were deceits and frauds. Her enemies plotted to drown her, but Germanus visited her again during this time and defended her, although the attacks continued. [5][15][9] The bishop of Paris appointed her to care for other consecrated virgins; "by her instruction and example she led them to a high degree of sanctity".[5]

Shortly before the attack of the Huns under Attila in 451 on Paris, Genevieve and Germanus' archdeacon persuaded the people of Paris that she "was not a prophetess of doom"[9] and instead of abandoning their homes, to pray and do acts of penance to spare the city. It is claimed that the intercession of Genevieve's prayers caused Attila's army to go to Orléans instead.[5][16][17] Jo Ann McNamara, the translator of Genevieve's vita, calls it a "prayer marathon" and Genevieve's "most famous feat".[4] According to her vita, Genevieve persuaded the women of Paris to undertake a series of fasts, prayers, and vigils "in order to ward off the threatening disaster, as Esther and Judith had done in the past".[18] She also persuaded the men to not remove their goods from Paris.[18]

Years later, Genevieve "distinguished herself by her charity and self-sacrifice"[5] during the defeat of Paris by Merowig and was able to influence him and his successors, Childeric and Clovis, to display clemency towards the city's residents.[5] According to Farmer, Genevieve made an agreement with soldiers during the siege of Paris to obtain provisions, transported by river from Arcis and Troyes.[2] Her vita reports that Clovis, who venerated her,[2] often pardoned criminals he had put in prison at Genevieve's request, even if they were guilty;[19] Attawater states that at Genevieve's request, Clovis freed prisoners and was lenient to lawbreakers.[6] According to Farmer, she "won Childeric's respect".[2] He ordered the Paris gates closed so Genevieve could not rescue prisoners he wanted to execute, but after Genevieve was informed of his plans, she opened the gates by touching them, without a key; she then met with Childeric and persuaded him not to execute the prisoners. She led a convoy through the blockade of Paris up the Seine from Troyes to bring food to the starving citizens. On her return home, Genevieve's prayers saved the eleven ships that carried her, her companions, and the grain for the residents of Paris.[6][20] Back in Paris, she prioritized giving food to the poor first.[21]

Genevieve had a strong devotion to Saint Denis of Paris and wanted to build a basilica in his honor, even though the local priests had few resources. She told them to the bridge of Paris, where they found an abandoned lime kiln, which provided the building materials for the basilica. After praying for an entire night, one of the priests promised to raise the funds needed to hire workers, and carpenters donated their time to gather wood and other resources. When the workers ran out of water to drink, Genevieve prayed and made the sign of the cross over a vessel, and water was miraculously provided. The basilica was later called the Priory of Saint Denis de Strata.[2][22]

Miracles

According to McNamara, during their many sieges of Paris, Genevieve had to convince the Franks "that she and her God were allies worth having".[4] McNamara also stated that Genevieve "aligned with the poor and the conquered against unharnessed secular power".[4] McNamara believed, however, that her status as a woman with no official status or political power "rendered her innocuous in the context of secular power"[4] and reported that it inspired the Franks to respect the Gallic saints. McNamara also states that Genevieve's prayers proved to the rulers on both sides that God responded to their requests. McNamara goes on to state, "Power, as expressed through miracles, protected Childeric and his successors from the possibility that whatever mercy and indulgence they showed towards the saints and to the poor they championed might be construed as a sign of weakness unbecoming a warrior".[4]

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, Genevieve had frequent visions of heavenly saints and angels.[5] Genevieve's vita reported that she rekindled a candle after it went out on the way from her cell to the Basilica of Saint-Denis; the virgins with her were frightened, so she asked to hold the candle and it immediately lit up again. When she arrived at the basilica, the candle was consumed by its own fire and after completing her prayers, another candle was lit when she touched it.[23] As her vita reports, "They say that the candle in her cell lit up in her hand without being kindled by fire".[24] People were healed when they procured fragments of her candle.[24] Genevieve's vita states that when a woman stole Genevieve's shoes, she was struck blind when she arrived at her home; someone led her back to Genevieve, and after asking for her forgiveness, was healed by Genevieve.[24] Her vita also reports that she was able to discern that a young woman was lying about her chastity and that "she restored vision, strength, and life to various people".[25]

She also healed a nine-year-old girl from Lyon and healed, by the laying on of her hands, a young girl who had not been able to walk for two years due to illness.[26] Genevieve raised a four-year-old boy, the son of a woman she had healed of demon possession, who had fallen into a well and drowned; his mother brought him to Genevieve, who prayed until he came back to life. The boy was baptised on Easter and was subsequently called Cellomerus because he "had recovered his life in [her] cell".[27] Also during Easter, she healed a woman who had been struck blind with prayers and with the sign of the cross. She healed a man from Meaux who had a withered hand and arm; she prayed for him, touched his arm and joints, made the sign of the cross over him, and he was restored to health in 30 minutes. She released twelve people who lived in Paris of demon possession; she ordered them to go to the Basilica of Saint-Denis and healed them after making the sign of the cross over each of them.[27]

Genevieve was asked to heal the wife of a tribune of paralysis, which was done with prayer and the sign of the cross. While in Troyes, many people were brought to her for healing, including a sick child who was healed after drinking water she had blessed, as well as a man struck with blindness, whom the writer of her vita reported had been punished for working on Sunday. Her vita also reported that many people, including those suffering from demon possession, had been healed after tearing off parts of her garments.[28] She healed a city official, who had been struck with deafness for four years, by touching his ears while making the sign of the cross over them. Her vita describes miracles that happened in Orléans through her intercessions, including raising the daughter of a family's matriarch from the dead and healing a man who became ill because he refused to forgive his servant.[29] Genevieve then visited Tours, "braving many perils on the River Loure";[30] she was greeted there by a crowd of people possessed by demons, whom she healed, with prayers and the sign of the cross, in the Basilica of Saint Martin. Some victims reported that Genevieve's fingers "blazed up one by one with celestial fire" while healing them.[31] She also healed three women of demon possession privately, in their homes, and at the request of their husbands. Genevieve's vita reports that in Tours, "everyone honored her in her comings and goings".[31] Her vita also reports that near Genevieve's home, she was able to spot and remove a demon from the opening of a water vessel.[32]

The parents of a young boy brought her their son, whom she healed of blindness, deafness, and paralysis by making the sign of the cross and rubbing oil on him. Her prayers protected a harvest near Meaux from a whirlwind during a rainstorm; neither the reapers nor the crops were touched by any water. Another time, while traveling by ship on the Seine, her prayers saved the ship; her vita makes the connection between this and the miracle of Christ calming the storm in the Gospels.[33] Genevieve would often use blessed oil to anoint and heal the sick. Her vita reports that on one occasion, she sent for a vessel with oil that was supposed to have been blessed by a bishop, but after she prayed for an hour, the vessel was miraculously filled with oil and she was able to heal someone from demon possession.[34]

Death and influence

Genevieve's vita states that "she passed over in ripe old age, full of virtue",[35] at the age of over 80 years old. Her feast day is January 3.[2] Her vita reports two miracles of healing that occurred at her grave.[19] Genevieve's attributes are most commonly a candle,[2] as well as bread, keys, herd, and cattle. Sometimes Genevieve is depicted with or without the devil, who is said to have blown out the candle when she went to pray in the church at night.[2]

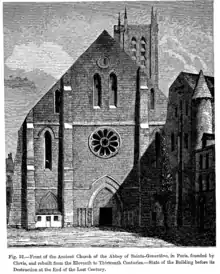

After Genevieve's death, she was enshrined in the Church of Saints Peter and Paul, where many miracles occurred and which was later renamed Saint Genevieve's Church.[2] Clovis began the construction, in her honor, of a basilica that was completed by his wife, Queen Clothilde, after his death.[19] Genevieve's vita states, about the basilica, "A triple portico adjoins the church, with pictures of Patriarchs and Prophets, Martyrs and Confessors to the faith in ancient times from pages of history books".[36] Under the care of the Benedictines, who established a monastery there, the church witnessed numerous miracles wrought at her tomb. As Genevieve was popularly venerated there, the church was dedicated to her. People eventually enriched the church with their gifts; it was plundered by the Vikings in 847 and was partially rebuilt, but was completed only in 1177.

As Farmer states, Genevieve's shrine "was carried in procession in times of disaster" during the Middle Ages and the citizens of Paris have "invoked her in times of national crisis" many times.[2] In 1129, during an epidemic of ergot poisoning, which Farmer called her most famous cure,[2] was stayed after Genevieve's relics were carried in a public procession. Up to 1993, the event was commemorated annually in the churches in Paris.[6] Her relics, which were honoured in a city-wide procession in 1694, resided in a side chapel at Saint Genevieve's Church (Church of Saint-Étienne-du-Mont).[37] The relics were involved in 120 public invocations between 1500 and 1793, with over one-third occurring during the 18th century, which art historian Hannah Williams found surprising because "superstitious spirituality, with miracle-working objects and cults of saints, sits uneasily with our idea of the eighteenth century as the 'age of reason'".[38] As Williams states, Genevieve's relics were "intimately tied to the city's history" and were called upon by the residents of Paris during times of crisis, "their faith rewarded with Saint Geneviève’s long and impressive record of miracles".[39] In 2016, Williams conducted an art-historical study of Genevieve's miracles, following four objects—her relics, two paintings, and Saint Genevieve's Church—across four events in the history of Paris, in order to demonstrate how their "use, reuse, transformations and appropriations reveal not religious decline, but shifting devotional practices and changing relationships with religious ideas and institutions" in Paris and throughout France.[39] Williams also sought to demonstrate, using Genevieve's objects, the inseparability of religion from 18th-century Paris life.[40]

Several churches were dedicated to her in Paris. Two churches in England, where five convents celebrated her feast, were dedicated to her during the Middle Ages, and her cult also spread to Southwest Germany.[2] Saint Genevieve's Church began to be rebuilt in 1746 because it had decayed; as Farmer states, it "was secularized at the Revolution and was called the Pantheon, a burial place for the worthies of France".[2] Louis XV ordered a new church worthy of the patron saint of Paris; he entrusted the Marquis of Marigny with the construction. The marquis gave the commission to his protégé Jacques-Germain Soufflot, who planned a neo-classical design. After Soufflot's death, the church was completed by his pupil, Jean-Baptiste Rondelet.

Genevieve's shrine and relics were mostly destroyed during the French Revolution, but as Farmer states, "this by no means finished her cult in France".[2] The most notable artistic representations of Genevieve, which continued traditions from the late Middle Ages, were created between the 17th and 19th centuries, including the frescoes of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes in the Pantheon.[2]

Her relics were publicly burnt and thrown into the Seine in 1793.[39] The Panthéon was restored to Catholic purposes in 1821. In 1831 it was secularized again as a national mausoleum but returned to the Catholic Church in 1852. Though the Communards were said to have dispersed the relics (there is no proof of this allegation, the relics having been burnt in 1793), some managed to be recovered. In 1885 the Catholic Church reconsecrated the structure to St. Genevieve. A portion of Genevieve's stone tomb currently resides in a large casket in the church; a smaller reliquary contains the bones of one finger.[39]

Canons of Saint Genevieve

About 1619 Louis XIII named Cardinal François de La Rochefoucauld abbot of Saint Genevieve's. The canons had been lax and the cardinal selected Charles Faure to reform them. This holy man was born in 1594, and entered the canons regular at Senlis. He was remarkable for his piety, and, when ordained, succeeded after a hard struggle in reforming the abbey. Many of the houses of the canons regular adopted his reform. In 1634, he and a dozen companions took charge of Saint-Geneviève-du-Mont of Paris. This became the mother-house of a new congregation, the Canons Regular of Ste. Genevieve, which spread widely over France.

Genevieve is the patron saint of Paris.[2] Her following and her status as patron saint of Paris were promoted by Clotilde, who may have commissioned the writing of her vita.[3] This was most likely written in Tours, where Clotilde retired after her husband's death, as evidenced also by the importance of Martin of Tours as a saintly model.

The institute named after the saint was the Daughters of Ste. Geneviève, founded at Paris in 1636, by Francesca de Blosset, with the object of nursing the sick and teaching young girls. A somewhat similar institute, popular buriel Miramiones, had been founded under the invocation of the Holy Trinity in 1611 by Marie Bonneau de Rubella Beauharnais de Miramion. These two institutes were united in 1665, and the associates called the Canonesses of Ste. Geneviève. The members took no vows, but merely promised obedience to the rules as long as they remained in the institute. Suppressed during the Revolution, the institute was revived in 1806 by Jeanne-Claude Jacoulet under the name of the Sisters of the Holy Family.

Music

Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Pour le jour de Ste Geneviève, H.317, motet for 3 voices, 2 treble instruments and continuo (? mid-1670)

See also

References

- Footnotes

- Notes

- "Genovefa (423-502)", p. 17

- Farmer, David Hugh (2011). "Genevieve". The Oxford Dictionary of Saints (5 ed.). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-19-959660-7.

- "Genovefa (423-502)", p. 18.

- McNamara, Jo Ann. "Introduction". In Sainted Women of the Dark Ages. Edited and translated from Acta Sanctorum by McNamara, Jo Ann; Halborg, John E. Durham; with Whatley, E. Gordon, England: Duke University Press. 1992. p. 4. ISBN 0-8223-1200-X. Retrieved 3 October 2023.

- MacErlean, Andrew (1909). "St. Genevieve". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- Attwater & John 1993, p. 152.

- "Genovefa (423-502)", p. 19.

- "Genovefa (423-502)", p. 20.

- Attwater & John 1993, p. 151.

- "Genovefa (423-502)", p. 21.

- "Genovefa (423-502)", pp. 21—22.

- "Genovefa (423-502)", p. 22.

- "Genovefa (423-502)", p. 24.

- "Genovefa (423-502)", pp. 24—25.

- "Genovefa (423-502)", pp. 22—23.

- Bentley, James (1993). A calendar of saints: the lives of the principal saints of the Christian Year. London: Little, Brown. p. 9. ISBN 9780316908139.

- Attwater & John 1993, p. 151-152.

- "Genovefa (423-502)", p. 23.

- "Genovefa (423-502)", p. 36.

- "Genovefa (423-502)", p. 28.

- "Genovefa (423-502)", p. 32.

- "Genovefa (423-502)", pp. 24—25.

- "Genovefa (423-502)", pp. 26—27.

- "Genovefa (423-502)", p. 27.

- "Genovefa (423-502)", p. 29.

- "Genovefa (423-502)", p. 28.

- "Genovefa (423-502)", p. 30.

- "Genovefa (423-502)", p. 31.

- "Genovefa (423-502)", p. 33.

- "Genovefa (423-502)", pp. 33—34.

- "Genovefa (423-502)", p. 34.

- "Genovefa (423-502)", pp. 34—35.

- "Genovefa (423-502)", p. 36.

- "Genovefa (423-502)", pp. 35—36.

- "Genovefa (423-502)", p. 36.

- "Genovefa (423-502)", pp. 36—37.

- Williams 2016, p. 322-323.

- Williams 2016, p. 323.

- Williams 2016, p. 322.

- Williams 2016, p. 325.

- Bibliography

- Attwater, Donald; John, Catherine Rachel (1993). The Penguin Dictionary of Saints (3 ed.). New York: Penguin. pp. 151–152. ISBN 0-14-051312-4. Retrieved 11 October 2023.

- "Genovefa (423-502)". Sainted Women of the Dark Ages. Edited and translated from Acta Sanctorum by McNamara, Jo Ann; Halborg, John E. Durham; with Whatley, E. Gordon, England: Duke University Press. 1992. pp. 17–37. ISBN 0-8223-1200-X. Retrieved 3 October 2023.

- Williams, Hannah (September 2016). "Saint Geneviève's Miracles: Art and Religion in Eighteenth-Century Paris" (PDF). French History. 30 (3): 322–353. doi:10.1093/fh/crv076.