St. Michael's Church, Berlin

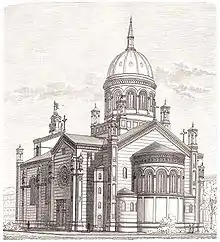

Saint Michael's (German: Sankt-Michael-Kirche) is a former Roman Catholic parish in Berlin, Germany, dedicated to the Archangel Michael. It is noted for its historic church in Mitte (former Luisenstadt), near the border between Berlin-Mitte locality and Kreuzberg. The church was built between 1851 and 1861, and also served as a garrison church for Catholic soldiers. It was heavily damaged by bombing during the Second World War and partially reconstructed in the 1950s. It is protected as a historical monument in Berlin.

Site

Saint Michael's is located on the Michaelkirchplatz in Engelbecken, which was part of the old Luisenstadt Canal, along which the Berlin Wall ran until German reunification. After the canal's closure in 1926, the space was converted into a park, which offered an uninterrupted view of St Michael's from the south. This view was opened up after the fall of the Berlin Wall, such that the church is once more seen in the way it was originally conceived. Michaelkirchstraße runs from Michaelkirchplatz to the River Spree, crossing Köpenicker Road, and has existed since the sixteenth century. In the immediate neighbourhood of the church, there are also monuments set up by the Haus des Deutschen Verkehrsbunds and the College of St Mary's Church.

History

Design (1846–1850)

The Protestant king Frederick William IV approved the construction of a second Roman Catholic church in Berlin after the Reformation, which was originally planned mainly as a church for the military garrison. It was intended to give Catholic soldiers living in Berlin a spiritual home and ease the pressure on St. Hedwig's Cathedral.

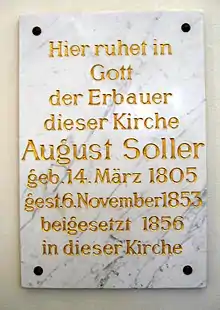

The architect August Soller completed the original design in 1845.[1] He planned a front facade with two towers, with Gothic elements, which he later abandoned. The plan envisioned the church would take the form of a "Zentralbau", but he later extended it into a hall church. As a result of the abandonment of the double-tower facade, the church now lacked a clearly visible profile. This could not be provided by the heavy octagonal roof planned for the cupola, so Soller substituted a domed tower, in accordance with earlier architectural models and the wishes of Frederick William IV.

Construction (1851–1856)

Frederick William IV had already named Michaelstraße after the Archangel Michael (in 1849 it became Michaelkirchstraße) and encouraged to the building commission's decision to place the church under the patronage of the Archangel Michael as well. On 14 July 1851, the foundation stone was laid, with the King and his family in attendance, along with church, secular, and military officials. Several thousand people lined the banks of the Engelbecken.[2]

Construction went on from 1851 until 1861.[1] Soller died during the construction and was buried inside in 1856. As a result of financial difficulties, construction of the church stalled for some time. The building was completed by Andreas Simons, Martin Gropius, and Soller's nephew, Richard Lucae.[3] In 1896, the cost of the church's construction was estimated at 438,000 marks. The church was consecrated on 28 October 1861, by the Bishop of Breslau, in the presence of William I, Emperor of Germany.

Military to civilian use

After the church's consecration in 1861, a military church area for 3,000 Catholic soldiers was established. Two years later, a local church district was added, which constantly grew until 1877. In 1888 it was promoted to a parish. With the settlement of the area around the church (which had still been wasteland when the church was begun), the parish expanded further. At its foundation, the area had 6,000 members, but by 1900 there were nearly 20,000 Roman Catholics in the parish, who were called "Michaelites."

Social conflict and engagement

Around 1900, the area around St Michael's, with its many tenements, was a social flashpoint. On 26 February 1892 there were large scale protests and riots due to unemployment. Members of the parish banded together to form a relief society, in order to reduce the problem. Marist sisters came from Breslau in 1888 and established the Marienstift in 1909, which endured until 1995. The Marienstift had social facilities, mobile health care, a kindergarten, and accommodation for servant girls. The Blessed Domprobst Bernhard Lichtenberg, who was later a prominent opponent of National Socialism, was chaplain at St Michael's from 1903 to 1905. The church's social engagement increased between 1917 and 1926 under Maximilian Kaller, who would also later become an opponent of the Nazis. Kaller brought members of the parish together as a lay apostolate for ensuring pastoral care.

Engelbecken

When the Luisenstadt Canal was closed in 1926, it was planned for the so-called Engelbecken ("Angel's pool"), named after the church's patron, to be converted into a public swimming pool. This outraged Berlin's Catholics. With the aid of the Centre Party, the approval of the plan by the Landtag of Prussia was blocked and the Engelbecken was turned into a pond for swans, surrounded by green space.

War damage and rebuilding

In the final months of the Second World War, on 3 February 1945, the Luisenstadt was nearly entirely destroyed by air raids carried out by the USAAF with over 950 aircraft. St Michael's suffered serious damage as a result of fire bombing. The organ and the majority of the church's interior were destroyed. The outer walls, domed tower and the front of the church remained largely intact. As a result of the destruction of the roof, the dome is seen through the portal window, which is below the bell tower. Abover the Portal, there is a mosaic depicting the annunciation, which partially survived the bombing as a result of the survival of the entranceway.

Services were accordingly shifted into the Marienstift. Under Franz Kusche, the Apse, sacristry, and the transept were rebuilt and services were able to be held within the church once more in 1953. In 1957, three new bells were installed and in 1960, the new organ was consecrated after the construction of a new space for it.

Division of the parish

With the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961, the parish was split into an eastern and a western half. St Michael's fell on the eastern side of the wall, so the Catholics of West Berlin erected their own Church of St. Michael on Waldemarstraße (Alfred-Döblin-Platz), immediately beyond the wall. This Western Church was designed by Rudolf Schwarz, who died in 1961; it was one of his last buildings. It was intended that the building would be able to serve as a church hall in the event of German Reunification. The centennial of St Michael's dedication was celebrated in October 1961.

During this period of separation, the two parts of the parish developed in very different ways. By the 1980s, the western part of the parish had expanded in Kreuzberg and become more focussed on youth, while the eastern part of the parish continued to employ traditional liturgy and services. This division continued after German Reunification and St. Michael's in the east now belongs to the parish of St. Hedwig's Cathedral, while the western part of the parish belongs to the parish of St. Mary's.

In 1978, the Church was given heritage status. From 1978 to 1980, the copper of the dome was replaced, the brickwork was repaired, and the new crucifix was remounted. In 1984, the parish house was moved from Michaelkirchstraße to a new parish house which was built in the ruins of the church between 1985 and 1988.

A clear view of St Michael's from the Oranienplatz was not possible between 1961 and 1990, because of the Berlin Wall. The lower half of the church, which could not be seen because of the concrete segments of the wall, was painted on the western part of the wall, as Trompe-l'œil, by the Berlin-based, Iranian artist Yadegar Asisi on the initiative of Berlin architect Bernhard Strecker, in order to demonstrate the "permeability" of the wall (Mauerdurchblick).[4][5][6][7] After the demolition of the wall, the Italian Marco Piccininni bought painted segments of the wall found near Waldemarbrücke n an auction at Monte Carlo in 1990, which he subsequently donated to the Vatican, where they were installed in the Vatican Gardens in August 1994.[8][9][10] Other graffiti on the Berlin Wall along Waldemarstraße is documented in ten connected poster-photos taken by photographers Liselotte and Armin Orgel-Köhne in 1985.[11]

After Reunification

After the Fall of the Berlin Wall, the Bell tower was refurbished and the statue of Michael was restored and returned to the tower (1991-1993). The mosaic depicting the Annunciation above the portal was restored again in 1999. Even now, however, the nave has no roof and services are held in the transepts. On 7 March 2001, the Association of Friends for the Protection of the Catholic Church of St Michael's of Berlin-Mitte was founded, to support activities connected with the church.[12]

On 31 October 2003, Archbishop Georg Sterzinsky decided to merge the parish of St Michael, which at that point had only 800 members, into the neighbouring parish of St Hedwig's Cathedral. Thus the church is no longer a parish church, although religious services continue to take place in it.

In August 2005, plans were revealed for the restoration of the nave and the installation of a Centre Against Expulsions in it from Autumn 2006. On 15 August 2005, the Archbishop made a statement saying that the church's agreement with the Federation of Expellees had been cancelled, "on account of a lack of community agreement with the installation of the centre in a church."[13]

Structure

Exterior

The three-aisled brick nave is 55 metres long, 30 metres high, and 19 metres wide. The church is topped by a tower over the crossing with a copper dome, which is over 56 metres high. On the corner columns of the crossing, there were statues of the Four Evangelists on high pedestals, before the church's damage during the Second World War.

The front facade has a bell tower with three round vaulted windows, but no towers. The statue of St Michael on the front facade is a replica of a statue made by the sculptor August Kiß for another purpose. The whole exterior is decorated with buttresses, friezes, and statues, as well as multi-coloured pricks.

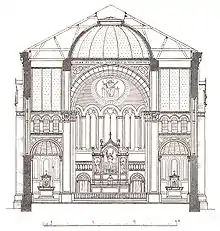

Interior

The church is a hall church, i.e. the three aisles of the nave were all of the same height (before they were destroyed in the war). The architect, Soller, originally planned the church as a "Zentralbau" (i.e. a building with rotational symmetry). He adapted this idea into a basilica structure, roofing each bay so that they appeared as a series of "Zentralbauten" arranged one after another.

The three aisles each end in an apse, as in Romanesque architecture. The two side apses used to contain altars dedicated to Mary and Joseph. The central apse, there is an image of the Archangel Michael locked in combat with Lucifer in the form of a dragon atop the high altar; the half-dome of the apse's ceiling contains a depiction of Jesus as Pantokrator.

Not all the decorations and images of the interior were restored during the post-war renovations. The original organ, now lost, was located in the matroneum above the main entrance. The pulpit is located on an eastern pillar of the crossing. There is also a tabernacle with a marble image of the Madonna on the altar, made by sculptor Heinrich Pohlmann.[14]

The transept is roofed by a barrel vault. After the partial destruction of the church, services were moved to the transept and as a result the eastern side entrance is now the main entrance to the church. The current organ is located in a new matroneum above the eastern entrance. This organ was made in 1960 by the W. Sauer Orgelbau Frankfurt company.

The west end of the transept now serves as the Choir and contains the altar. A two-level flat roof has been installed in the nave, which extends to the final columns before the transept. The rest of the old nave has been converted into a garden.

Architectural style

The church is considered a successful synthesis of Neoclassical and Medieval architecture. Soller drew on earlier architectural styles in a historicist manner. It is strongly influenced by Medieval and Renaissance churches of Padua and Venice. Soller had taken a five-month research trip through Italy in 1845, immediately before his first design work. The interaction between the water and architecture in Vencie was a particular inspiration. The facade with its filigree angels was based on San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice. The overall design, with its three apses and the vast nave is, however, heavily influenced by the church of San Salvador, Venice. The combination of the "Zentralbau" and hall church structures had a significant influence on several subsequent buildings of the Schinkel school in Berlin.

References

- Curran, Kathleen (2003). The Romanesque Revival: Religion, Politics, and Transnational Exchange. University Park, Penn: Pennsylvania State University Press. pp. 146–154. ISBN 0-271-02215-9.

- Bericht über die Grundsteinlegung der Garnison- und Pfarrkirche zum heiligen Michael

- Güttler, Peter, ed. (1984). Berlin und seine Bauten. Berlin: Ernst. ISBN 3-433-00995-3.

- Eine Zeitreise zurück an den Checkpoint Charlie. berlin.de

- Hermann Waldenburg: Berliner Mauerbilder. Nicolaische Verlagsbuchhandlung, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-87584-309-6, S. 55.

- Heinz J. Kuzdas: Berliner Mauer Kunst, mit East Side Gallery. Elefanten Press, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-88520-634-X, pp. 64 f.

- Ralf Gründer: Verboten. Berliner Mauerkunst. Böhlau, Köln 2007, ISBN 978-3-412-16106-4, pp. 266–268

- Hagen Koch: Where is the Wall? In: Berlinische Monatsschrift 7/2001; Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein.

- Ein Mauerstück für den Papst. Bemaltes Bauwerk in den Vatikanischen Gärten aufgestellt. In: Der Tagesspiegel, 28 February 1995.

- Paul Hoffmann: Glorious Gardens of the Vatican. In: The New York Times, 6 July 1997.

- Berlin – Seite für Seite. Literaturauswahl zur 750-Jahr-Feier. Bibliographie über Berlin, mit 10 Fotos (Ansichten des Teilstücks der Berliner Mauer an der Waldemarstraße). Hrsg.: Amerika-Gedenkbibliothek / Berliner Zentralbibliothek, Berlin 1986, ISBN 3-925516-04-2

- Homepage des Fördervereins

- Keine Bedenken gegen Ausstellung. In: Berliner Morgenpost, 17 August 2005.

- Berlin und seine Bauten. Wilhelm Ernst & Sohn, Berlin 1896. (Reprint 1984, ISBN 3-433-00995-3)

Bibliography

- Frank Eberhardt, Stefan Löffler (1995). Die Luisenstadt. Geschichte und Geschichten über einen alten Berliner Stadtteil. Berlin: Edition Luisenstadt. ISBN 3-89542-023-9.

- Manfred Klinkott (1988). Die Backsteinbaukunst der Berliner Schule. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. ISBN 3-7861-1438-2.

- Eva Börsch-Supan (1977). Berliner Baukunst nach Schinkel. 1840–1870. München: Prestel. ISBN 3-7913-0050-4.

External links

- Entry on the website of the Landesdenkmalamt Berlin.

- Friends of St. Michael's Church

- Home page of the Parish of St. Hedwig's Cathedral