Church of St Peter ad Vincula

The Chapel Royal of St Peter ad Vincula ("St Peter in chains") is a Chapel Royal and the former parish church of the Tower of London.The chapel's name refers to the story of Saint Peter's imprisonment under Herod Agrippa in Jerusalem. Situated within the Tower's Inner Ward, its current building dates from 1520, although the church was likely established in the 12th century. The church for working residents was the second chapel established in the Tower after St John's, a smaller royal chapel built into the 11th century White Tower. A royal peculiar, under the jurisdiction of the monarch, the priest responsible for these chapels is the chaplain of the Tower, a canon and member of the Ecclesiastical Household. The canonry was abolished in 1685 but reinstated in 2012.

| Church of St Peter ad Vincula | |

|---|---|

Side of St Peter chapel that faces the place of execution on Tower Green | |

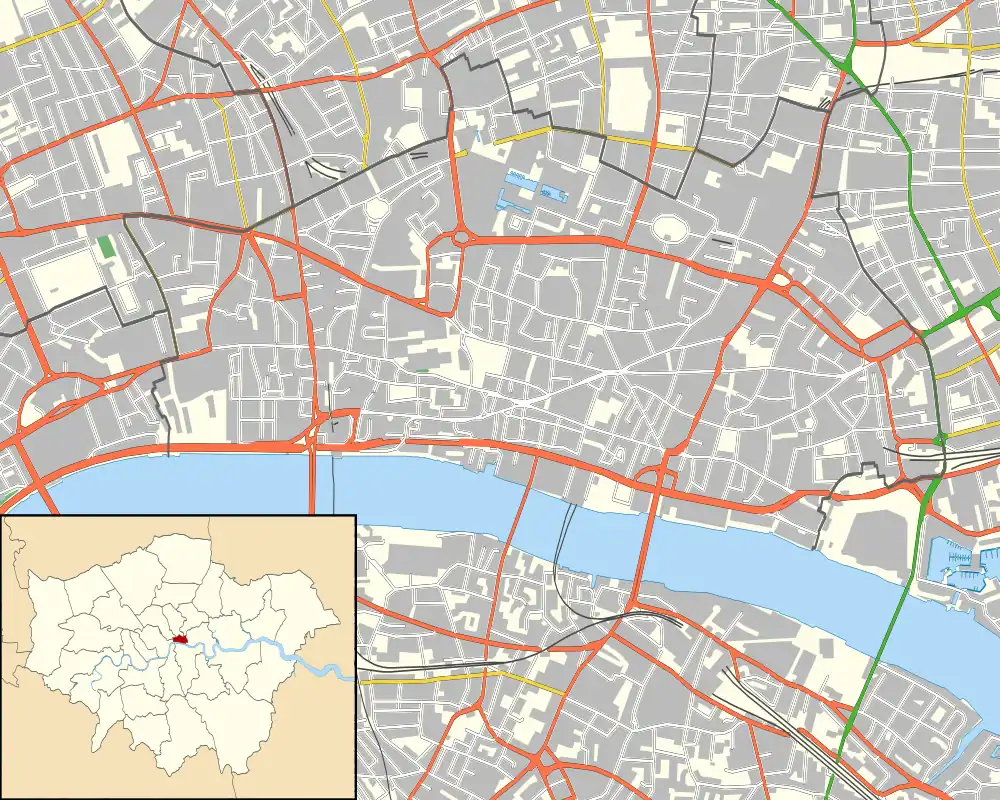

Church of St Peter ad Vincula The church in relation to the City of London | |

| 51°30′31″N 0°4′37″W | |

| Location | Tower Hamlets, London |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Originally Catholic, now Church of England |

| History | |

| Status | Active |

| Architecture | |

| Years built | 1519–20 |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | Royal Peculiar |

| Clergy | |

| Chaplain(s) | Roger Hall |

At St Peter's west end is a short tower, surmounted by a lantern bell-cote, and inside the church is a nave and shorter north aisle, lit by windows with cusped lights but no tracery, a typical Tudor design. The Chapel is probably best known as the burial place of some of the most famous prisoners executed at the Tower, including Queen Anne Boleyn, Queen Catherine Howard, the "nine-day Queen", Lady Jane Grey (with her husband Lord Guildford Dudley) and Sir Thomas More.

History

The original foundation date and location for the chapel is unknown. The chapel has been destroyed, rebuilt, relocated and renovated several times. Some have proposed that the chapel was founded before the Norman conquest of England as a parish church, predating the use of the area as a fortification.[1] Others have concluded the chapel was founded by Henry I (r. 1100–1135),[2] and perhaps consecrated on 1 August 1110 on the feast of St Peter ad Vincula.[1] The chapel would have been outside the Tower's original perimeter walls so that the king could be seen worshiping in public. It would have stood in contrast to the king's use of the more private St John's Chapel, established around 1080 by William I inside the White Tower.[3]

St Peter ad Vincula had been a parish church for at least a century before it became the chapel for the inhabitants of the Tower in the middle of the thirteenth century in the reign of Henry III,[1] and the crypt under the church was built at that time.[4] On 10 December 1241, Henry III issued a writ of liberate to have the ecclesia sancti Petri infra ballium Turris nostrae London (church of St Peter within the bailey of our Tower of London) enhanced. The writ indicates that by 1241 the chapel had been brought within the Tower walls. This structure had two chancels, dedicated to St Mary, and to St Peter; the latter contained Royal stalls that were wainscoted and painted, and there were two altars dedicated to St. Nicholas and St. Katherine.[5][6]

During the reign of Henry III, the church had an enclosed cell for an anchorite, which would have been directly attached or located nearby.[7] Henry III supported the living expenses of at least three different recluses, both men and women, at the Tower's anchorhold: Brother William,[8] Idonee de Boclaund (an anchoress),[9] and Geoffrey le Hermit.[10] After 1312, it is likely the ceremonial vigil related to the induction of the Knights of the Bath were held in the church.[11]

The chapel's dedication to "St Peter ad Vincula" has several possible meanings in the Norman-English context. The most obvious is in reference to the Liberation of Peter from prison, as first mentioned in Acts 12:3-19. The first prisoner of the Tower, Ranulf Flambard, the Norman Bishop of Durham, was incarcerated by Henry I on 15 August 1100.[12]

Current edifice

The existing building was rebuilt for Henry VIII[13] by the then Lieutenant of the Tower, Sir Richard Cholmondeley (whose tomb is in the Church), between 1519 and 1520, after a fire destroyed the church in 1512. The rebuilt chapel was probably designed by William Vertue.[14]

Parish of the Tower of London

St Peter ad Vincula was the church of the extra-parochial area of Tower Within, part of the Liberties of the Tower of London.[15] On 16 December 1729 the church was added to the Bills of mortality, a record of burials in London, but was excluded in 1730 because of a successful claim by the inhabitants of it being extra-parochial and outside of the normal parish system.[16] Extra-parochial places were eliminated in the 19th century, and in 1858 the area became a civil parish, following the Extra-Parochial Places Act 1857.[17] The Tower of London liberty was dissolved in 1894,[18] and the parish was absorbed by St Botolph without Aldgate in 1901.[17] The Chapel is also the regimental church of The Royal Regiment of Fusiliers, whose connections with the Tower of London go back the 1685 raising of the Royal Fusiliers to guard the Tower and the Artillery train kept there. Officers of the regiment retain the right to get married there.[19]

Burials and monuments

The church contains many splendid monuments. In the north-west corner is a memorial to John Holland, Duke of Exeter, a Constable of the Tower, who died in 1447. Under the central arcade lies the effigy of Cholmondeley, who died in 1521, the year after he completed the rebuilding of the church.[1] In the sanctuary, there is an impressive monument to Sir Richard Blount, who died in 1564 and is buried in the church, and his son Sir Michael, died in 1610, both Tudor Lieutenants of the Tower, who would have witnessed many of the executions.[20] There is a fine 17th-century organ, decorated with carvings by Grinling Gibbons.

The church is the burial place of some of the most famous Tower prisoners, including Queen Anne Boleyn and Queen Catherine Howard, the second and fifth wives of King Henry VIII, respectively, and Lady Jane Grey, who was Queen of England for nine days in 1553.[21] George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford, brother of Anne, was also buried here after his execution in 1536, as were Edmund Dudley and Sir Richard Empson, tax collectors for King Henry VII, and Lord Guildford Dudley, husband to Lady Jane Grey, in February 1554, after being executed on Tower Green. Others were Sir Thomas More and Bishop John Fisher, who incurred the wrath of King Henry VIII, and after their execution, they were canonised as martyrs by the Roman Catholic Church; Philip Howard, a third saint who suffered under the Tudors, was also buried here for a time before his body was relocated to Arundel.[1] After their executions, the following people were also buried here: King Henry VIII's minister, Thomas Cromwell (1540);[22] Thomas Seymour, 1st Baron Seymour of Sudeley, the brother of Jane Seymour, uncle of Edward VI, who is remembered for his unseemly conduct towards his step-niece, Elizabeth I (1549);[23] Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset (1552); John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland and John Gates in connection with the 1553 succession crisis (1553); and James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth, under the communion table (1685).[24]

A list of "remarkable persons" buried in the chapel between 1534 and 1747 is listed on a table on the west wall.[1] Thomas Babington Macaulay memorialised those buried in the chapel in his 1848 History of England:

In truth there is no sadder spot on the earth than that little cemetery. Death is there associated, not, as in Westminster Abbey and Saint Paul's, with genius and virtue, with public veneration and with imperishable renown; not, as in our humblest churches and churchyards, with everything that is most endearing in social and domestic charities; but with whatever is darkest in human nature and in human destiny, with the savage triumph of implacable enemies, with the inconstancy, the ingratitude, the cowardice of friends, with all the miseries of fallen greatness and of blighted fame. Thither have been carried, through successive ages, by the rude hands of gaolers, without one mourner following, the bleeding relics of men who had been the captains of armies, the leaders of parties, the oracles of senates, and the ornaments of courts.[25]

During renovation work in 1876 three burials were discovered, identified as Anne Boleyn, Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury, and John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland.[26][27][28]

Chapel Royal

The church is a Chapel Royal and the priest responsible for it is the chaplain of the Tower of London, a canon and member of the Ecclesiastical Household. The canonry was abolished in 1685 but reinstated in 2012. The Reverend Roger Hall, MBE was installed as a canon the same year.[29]

The chapel can be visited as part of a specific tour within the Tower of London or by attending the regular Sunday morning service.

References

- "Chapel of St Peter Ad Vincula", Camelot International: The Tower of London (2007)

- George Leyden Hennessy, Novum Repertorium Ecclesiasticum Parochiale Londinense (1898), vol. 2, p. 372

- J. Nicholls, The Chapels Royal of St Peter ad Vincula and St John the Evangelist, H. M. Tower of London, p. 3, Pitkin Pictorials, (1971)

- Poyser, Arthur. The Tower of London, A. & C. (1908), pp. 131–132

- Rot. Lib. 25 Henry III m. 20. 2005.

- Bayley, John. The History and Antiquities of the Tower of London Part I (1821), p. 118

- Bayley, John. The History and Antiquities of the Tower of London Part I (1821), p. 129

- "Rot. Claus. 21 Hen III m. 15". 1902.

- Rot. Claus. 37 Hen III m. 2. H.M. Stationery Off. 1902.

- The National Archives of the UK (TNA): Ancient Correspondence SC1/30/87

- "St John's Chapel". Historic Royal Palaces. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- Huscroft, Ruling England, p. 68, Pearson/Longman (2005)

- Tabor, M. "The City Churches", p. 44, London: The Swarthmore Press (1917)

- Curl, J. and S. Wilson, Oxford Dictionary of Architecture, 3rd ed. (2015), p. 807

- Burn, Richard; John Burn (1793). The Justice of the Peace, and Parish Officer, Volume 1.

- Miller, A. (1759). Collection of Yearly Bills of Mortality, from 1657 to 1758 Inclusive.

- Youngs, Frederic A Jr. (1979). Guide to the Local Administrative Units of England, Vol. I: Southern England. London: Royal Historical Society. pp. 556–707. ISBN 0-901050-67-9.

- "Tower of London", Star, Issue 5033, 20 August 1894, p. 3

- ‘The Royal Regiment of Fusiliers Regimental Handbook. RRF. 2019.’‘

- "St Peter ad Vincula, Tower of London, Tower Hill, London EC3: tourist information", TourUK, accessed 7 February 2013

- Tallis, Nicola (6 December 2016). Crown of Blood: The Deadly Inheritance of Lady Jane Grey. Pegasus Books. ISBN 9781681772875 – via Google Books.

- Bell, Doyne Courtenay. Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex, Notices of the historic persons buried in the chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula, J. Murray (1877), p. 109

- Bell, Doyne Courtenay. Notices of the Historic Persons Buried in the Chapel of St. Peter Ad Vincula. J. Murray (1877), pp. 127–134

- "James Scott, Duke of Monmouth" Archived 2014-07-14 at the Wayback Machine, Family Search, accessed 12 June 2014

- Macaulay, Thomas Babington. The History of England from the Accession of James II, 5 vols. (1848)

- "Pole, Margaret, suo jure countess of Salisbury (1473–1541), noblewoman". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/22451. Retrieved 18 November 2020. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Bell, Doyne C. (1877). Notices of the Historic Persons Buried in the Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula in the Tower of London. London: John Murray, Albemarle Street. pp. 24–29.

- Warnicke, Retha M. (1991). The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn: Family Politics at the Court of Henry VIII. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 235. ISBN 9780521406772.

- "Reverend Roger Hall becomes Tower's first Canon for 300 years" Archived 2014-01-19 at the Wayback Machine, Historic Royal Palaces, accessed 21 February 2014