SpaceX Starship

Starship is a two-stage super heavy lift launch vehicle and spacecraft under development by SpaceX. It is currently the tallest and most powerful space launch vehicle to have flown.[lower-alpha 2] Starship is intended to be fully reusable, enabling the vehicle to be recovered after a mission and reused.

Starship system in launch configuration: Starship spacecraft sits on top of Super Heavy. | |

| Function | |

|---|---|

| Manufacturer | |

| Country of origin |

|

| Project cost | at least US$3 billion[lower-alpha 1][1] |

| Size | |

| Height | 121 m (397 ft) |

| Diameter | 9 m (30 ft) |

| Mass | 5,000,000 kg (11,000,000 lb) |

| Stages | Super Heavy booster and Starship spacecraft |

| Capacity | |

| Payload to LEO | 100t – 150t (reusable) Up to 250t (expendable) |

| Launch history | |

| Status | In development |

| Launch sites | SpaceX Starbase Kennedy Space Center, LC-39A (planned) |

| Total launches | 1 |

| Success(es) | 0 |

| Failure(s) | 1 |

| Partial failure(s) | 0 |

| First flight | 20 April 2023 |

The Starship space vehicle is designed to supplant SpaceX's Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets, build SpaceX's Starlink satellite constellation, and serve crewed spaceflight. SpaceX plans to use Starship vehicles as tankers, refueling other Starships to allow missions to geosynchronous orbit, the Moon, and Mars. A lunar lander variant of Starship is to land astronauts on the Moon as part of NASA's Artemis program. Starship is ultimately meant to enable SpaceX's ambition of colonizing Mars.

Starship is made up of a booster and the Starship spacecraft. The booster and spacecraft are both powered by clusters of Raptor rocket engines, which burn liquid methane and liquid oxygen.The vehicle is constructed primarily of stainless steel, a material chosen as an alternative to a series of prior designs. The Starship spacecraft is protected during atmospheric reentry by its thermal protection system, and, like the booster, lands vertically by decelerating using its main rocket engines.

The Starship system aims to achieve frequent space launches at low cost. Development follows an iterative and incremental approach involving frequent, and often destructive, test flights of prototype vehicles.[2] The first flight test of the Starship system took place on 20 April 2023 and ended four minutes after launch with the destruction of the test vehicle.

History

Early design conceptions

Starting with a 2012 announcement of plans to develop a rocket with substantially greater capabilities than SpaceX's existing Falcon 9, the company created a succession of preliminary designs for such a vehicle under various names (Mars Colonial Transporter, Interplanetary Transport System, BFR). Some were substantially different from the current design; the largest one, the Interplanetary Transport System or ITS, massed 10,500 t (23,100,000 lb) fully fueled, had a liftoff thrust of 128 meganewtons (29,000,000 lbf) and could carry 300 tonnes (660,000 lb) to low Earth orbit while being completely reused. By comparison, the Saturn V had a liftoff thrust of 36 MN (8,000,000 lbf).[3][4] It also was made of carbon composite.[3][5] Despite this, they all shared some common features such as being fully reusable and being very large. This lead to a 2019 adoption of a stainless-steel body design, which is also when the name changed to Starship.

The two major parts were renamed to Starship (second stage) and Super Heavy (booster stage).[6] In 2019, SpaceX began to refer to the Starship / Super Heavy combination as the Starship system.[7][8][9][10] In September 2019, Musk further detailed the lower-stage booster, the upper-stage's method of controlling its descent, the heat shield, orbital refueling capacity, and potential destinations besides Mars.[11] The aft flaps on the spacecraft were reduced from three to two.

Starship's structural material was changed from carbon composites to stainless steel.[12] Musk cited the low cost and ease of manufacture, increased strength of stainless steel at cryogenic temperatures, as well as its ability to withstand high heat, as the reasons for the design change.[13][12] The high temperature at which 300-series steel transitions to plastic deformation would eliminate the need for a heat shield on Starship's space-facing side, while the much hotter Earth-facing side would be cooled by allowing fuel or water to bleed through micropores in a double-wall stainless steel skin, removing heat by evaporation. However, in July 2019 Musk indicated on Twitter that this would probably not be pursued, but that thin reusable heat shield tiles which work in a similar way to those of the Space Shuttle would be used. The high melting point of Starship’s stainless steel would mean that the tiles could be lighter and thinner.[14]

In 2019, the design reverted to six Raptor engines, with three optimized for sea-level and three optimized for vacuum. Initial Super Heavy test flights would use fewer engines, perhaps about 20.

Later in 2019 Musk stated that Starship was expected to have an empty mass of 120,000 kg (260,000 lb) and be able to initially transport a payload of 100,000 kg (220,000 lb), growing to 150,000 kg (330,000 lb) over time. Musk hinted at an expendable variant that could place 250 tonnes into low orbit.[15]

The Raptor design was refined with higher thrust versions. The initial 37 engines were reduced to 31 in 2020. Musk stated that SpaceX would complete hundreds of cargo flights before carrying human passengers.[16] In April 2021, SpaceX publicly forecast that Earth to Earth passenger flights would be common within five years.[17]

Low-altitude flights

SpaceX was already constructing the first full-size Starship Mk1 and Mk2 upper-stage prototypes, at the SpaceX facilities in Boca Chica, Texas, and Cocoa, Florida, respectively.[11] Neither prototype flew: Mk1 was destroyed in November 2019 during a pressure stress test and Mk2's Florida facility was abandoned and deconstructed throughout 2020.[18][19] After the Mk prototypes, SpaceX began naming its new Starship upper-stage prototypes with the prefix "SN", short for "serial number".[20] No prototypes between SN1 and SN4 flew either—SN1 and SN3 collapsed during pressure stress tests, and SN4 exploded after its fifth engine firing.[21]

In June 2020, SpaceX started constructing a launch pad for orbit-capable Starship rockets.[22] The first flight-capable Starship, SN5, was cylindrical as it had no flaps or nose cone: just one Raptor engine, fuel tanks, and a mass simulator. On 5 August 2020, SN5 performed a 150 m (500 ft) high flight and successfully landed on a nearby pad.[23] On 3 September 2020, the similar-looking Starship SN6 repeated the hop;[24] later that month, the Raptor Vacuum engine was fired in full duration at McGregor, Texas.[25]

High-altitude flights

Starship SN8 was the first fully complete Starship upper-stage prototype. It underwent four preliminary static fire tests between October and November 2020.[21] On 9 December 2020, SN8 flew, slowly turning off its three engines one by one, and reached an altitude of 12.5 km (7.8 mi). After SN8 dove back to the ground, its engines were hampered by low methane header tank pressure during the landing attempt, which led to a hard impact with the landing pad.[26] Because SpaceX had violated its launch license and ignored warnings of worsening shock wave damage, the Federal Aviation Administration investigated the incident for two months.[27]

On 2 February 2021, Starship SN9 launched to 10 km (6.2 mi) in a flight path similar to SN8. The prototype crashed upon landing because one engine did not ignite properly.[28] A month later, on 3 March, Starship SN10 launched on the same flight path as SN9. The vehicle landed hard and crushed its landing legs, leaning to one side.[29] A fire was seen at the vehicle's base. It exploded less than ten minutes later,[30] probably due to a propellant tank rupture.[29] On 30 March, Starship SN11 flew into thick fog along the same flight path.[31] The vehicle exploded during descent,[31] possibly due to excess propellant in a Raptor's methane turbopump.[32]

In March 2021, the company disclosed a public construction plan for two sub-orbital launch pads, two orbital launch pads, two landing pads, two test stands, and a large propellant tank farm. The company soon proposed developing the surrounding Boca Chica Village, Texas into a company town named Starbase.[33] Locals raised concerns about SpaceX's authority, power, and a potential threat for eviction through eminent domain.[34] In early April, the orbital launch pad's fuel storage tanks began mounting.[22] Starship prototypes SN12, SN13, and SN14 were scrapped before completion; SN15 was selected to fly instead.[35] SN15 had better avionics, structure, and upgraded engines.[30] On 5 May 2021, SN15 launched, completed the same maneuvers as older prototypes, and landed safely.[35] Even though SN15, like SN10, had a small fire in the engine area after landing, it was extinguished, completing the first successful high-altitude test.[30] According to a later report by SpaceX, SN15 experienced several issues while landing, including the loss of tank pressure and an engine.[36]: 2

Development towards first orbital launch

In July 2021, Super Heavy BN3 conducted its first full-duration static firing and lit three engines.[37] Around this time, SpaceX changed their naming scheme from "SN" to "Ship" for Starship crafts,[38] and from "BN" to "Booster" for Super Heavy boosters.[39] A month later, using cranes, Ship 20 was stacked atop Booster 4 to form the full launch vehicle for the first time; Ship 20 was also the first craft to have a body-tall heat shield.[40] In October 2021, the catching mechanical arms, also known as "chopsticks", were installed onto the integration tower and the first tank farm's construction was completed.[22] Two weeks later, NASA and SpaceX announced plans to construct Kennedy Space Center's Launch Complex 49.[41]

The public spotted the Raptor 2 engine at the start of 2022. Raptor 2 has a simpler design, less mass, wider throat, and an increase in central combustion chamber pressure from 250 bar (3,600 psi) to 300 bar (4,400 psi). These changes yielded an increase in thrust from 1.85 MN (420,000 lbf) to 2.3 MN (520,000 lbf), but a decrease of 3 seconds (~0.9%) of specific impulse.[42] In February 2022, after stacking Ship 20 on top of Booster 4 using mechanical arms, Elon Musk gave a presentation on Starship, Raptor engine and Florida spaceport development at Starbase.[43]

In June 2022, the Federal Aviation Administration determined that Starbase did not need a full environmental impact assessment but that SpaceX must address issues identified in the preliminary environmental assessment.[44] In July, Booster 7 tested spinning the liquid oxygen turbopumps on all thirty-three Raptor engines, resulting in an explosion at the vehicle's base, which destroyed a pressure pipe and causing minor damage to the launchpad.[45] By the end of November, Ship 24 had performed 2- and full 6-engine static test fires,[46]: 20 while Booster 7 had performed static fires with 1, 3, 7, 14, 11 engines[47][46]: 20 and finally on 9 February 2023 a static fire with 31 engines at 50% throttle (33 was attempted but one engine was disabled pre-firing, and another engine aborted). In January 2023, Starship underwent a full wet dress rehearsal at Starbase, where it was filled with more than 4,500 t (10,000,000 lb) of propellant.[48]

First attempted orbital test flight

.jpg.webp)

After a canceled launch attempt on 17 April 2023, due to a frozen valve,[49] Booster 7 and Ship 24 lifted off on 20 April at 13:33 UTC in the first orbital flight test.[50] Three engines were disabled during the launch sequence and several more failed during the flight.[51] The spacecraft also lost thrust vectoring control of the Raptor engines later in the flight, which led to the rocket starting an out of control tumbling motion.[51] The vehicle reached a maximum altitude of 24 mi (39 km).[52]

At around 3 minutes following liftoff, the rocket received a command to activate the automated flight termination system. However, the flight termination system failed to destroy the vehicle, the vehicle tumbled for another 40 seconds, and finally exploded.[53][54][55] Had the launch proceeded as planned, the spacecraft would have continued to fly with its ground track passing through the Straits of Florida and eastward around the globe, with a hard splashdown in the Pacific Ocean around 100 km (60 mi) northwest of Kauai in the Hawaiian Islands, having made nearly one full revolution around the Earth.[56][57]: 2–4

Preparations for the second orbital test flight

After the first test flight significant work was done on the launch mount to repair the damage it sustained during the test and to prevent future issues. The foundation of the launch tower was reinforced and a steel water deluge flame deflector was built under the launch mount.[58] Ship 25 was rolled to the suborbital launch site in May and underwent spin prime and static fire testing ahead of flight. Once that was completed, Booster 9 was rolled to the launch site to undergo cryogenic proof testing, spin primes and static fires of its set of engines. As of September 7th, Ship 25 is stacked onboard Booster 9 on the launch mount.[59]

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) oversaw the investigation of Starship's first flight failure, at the end of which SpaceX reported it had identified 63 needed corrective actions before another Starship launch license could take place.[60][61][62] On September 8, 2023, the FAA concurred with SpaceX's report and closed the investigation.[61] The FAA also announced that the full investigatory report would not be released due to confidential contents including export control information.[60] FAA officials stated, "The closure of the mishap investigation does not signal an immediate resumption of Starship launches at Boca Chica."[63] A launch license approval from the FAA could come as early as October.[64][65] The United States Fish and Wildlife Service has yet to start a formal review of SpaceX's modifications, and depending on the situation, the next launch may not occur until 2024.[66][67] The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service received the final biological assessment from the Federal Aviation Administration. William Gerstenmaier, SpaceX’s Vice President of Build and Flight Reliability, called for the FAA to increase licensing staff.[68][69] On October 19, the FWS surveyed the area around Starbase and the consultation with the FAA has been extended into November.[70][71]

Funding

As part of the development of the Human Landing System for the Artemis program, SpaceX was awarded in April 2021 a $2.89 billion contract from NASA to develop the Starship lunar lander for Artemis III.[72][73] Blue Origin, a bidding competitor to SpaceX, disputed the decision and began a legal case against NASA and SpaceX in August 2021, stalling the work of SpaceX and NASA on the program with SpaceX for the duration of these legal disputes.[74] It was dismissed by the Court of Federal Claims after three months,[75][76] and Blue Origin was awarded $3.4 billion for their lunar lander two years later.[77]

In 2022, NASA awarded SpaceX $1.15 billion for a second lunar lander for Artemis 4.[73] The same year, SpaceX was awarded a $102 million five-year contract to develop the Rocket Cargo program for the United States Space Force.[78]

SpaceX develops the Starship with private funding.[79][80][81] SpaceX Chief Financial Officer Bret Johnsen disclosed in court that SpaceX has invested more than $3 billion into the Starbase facility and Starship systems from July 2014 to May 2023.[81] Elon Musk stated in April 2023 that SpaceX expects to spend about $2 billion on Starship development in 2023.[82][83]

Design

When stacked and fully fueled, Starship has a mass of approximately 5,000 t (11,000,000 lb)[lower-alpha 3], a diameter of 9 m (30 ft),[86] and a height of 121 m (397 ft).[87] The rocket has been designed with the goal of being fully reusable to reduce launch costs and maintenance between flights.[88] In its fully reusable configuration Starship is designed to carry 150 t (330,000 lb) to low Earth orbit, while the expended configuration is projected to have a payload capacity of 250 t (550,000 lb).[89]

The rocket consists of the Super Heavy first-stage or booster, and the Starship second-stage or spacecraft,[90] powered by the Raptor and Raptor Vacuum engines.[91] The bodies of both rocket stages are made from stainless steel, giving Starship its strength for atmospheric entry and distinctive look.[92]

According to Eric Berger of Ars Technica, the manufacturing process starts with rolls of steel, which are unrolled, cut, and welded along the cut edge to create a cylinder of 9 m (30 ft) in diameter, 2 m (7 ft) in height, and 4 mm (0.16 in) thick, and around 1,600 kg (4,000 lb) in mass. These cylinders, along with the nose cones, are stacked and welded along their edges to form the outer layer of the rocket. Inside, the methane and oxygen tanks are separated by the robot-made domes.[93] Also according to Berger, Starship's reusability and stainless-steel construction has influenced the Terran R rocket[94] and Project Jarvis, the second stage of Blue Origin's New Glenn super heavy-lift launch vehicle.[95]

Raptor engine

Raptor is a family of rocket engines developed by SpaceX exclusively for use in Starship and Super Heavy vehicles. It burns liquid oxygen and methane in a highly efficient but complex full-flow staged combustion power cycle. The Raptor engine uses methane as the fuel of choice over other rocket propellants because it produces less soot[96] and can be directly synthesized from carbon dioxide and water, using the Sabatier reaction.[97] Unlike previous reusable rocket engines such as the RS-25, the engines are designed to be reused many times with little maintenance.[98]

The engine structure itself is mostly aluminum, copper, and steel; oxidizer-side turbopumps and manifolds subject to corrosive oxygen-rich flames are made of an Inconel-like SX500 superalloy.[42] Raptor's main combustion chamber can contain 300 bar (4,400 psi) of pressure, the highest of all rocket engines.[96] Certain components are 3D printed. The Raptor's gimbaling range is 15°, higher than the RS-25's 12.5° and the Merlin's 5°. In mass production, SpaceX aims to produce each engine at a unit cost of US$250,000.[42]

Raptor operates with an oxygen-to-methane mixture ratio of about 3.6:1, lower than the stoichiometric mixture ratio of 4:1 necessary to burn all propellants completely. Operation at the stoichiometric ratio provides better performance in theory but usually results in overheating and destruction of the engine.[84] The propellants leave the pre-burners. They are injected into the main combustion chamber as hot gases instead of liquid droplets, enabling much higher power density as propellants mix rapidly via diffusion.[96] The methane and oxygen are at such high temperatures and pressures that they ignite on contact, eliminating the need for igniters in the main combustion chamber.[42]

At sea level, the standard Raptor engine produces 2.3 MN (520,000 lbf) at a specific impulse of 327 seconds, increasing to 350 seconds in a vacuum.[42] Raptor Vacuum, used on the Starship upper stage, is modified with a regeneratively cooled nozzle extension made of brazed steel tubes, increasing its expansion ratio to about 90 and its specific impulse in vacuum to 380 seconds.[84] Another engine variant, Raptor Boost, is exclusive to the Super Heavy booster; the engine variant lacks thrust vectoring and has limited throttle capability in exchange for increased thrust.[99][42]

Super Heavy booster

The first-stage booster, named Super Heavy is 71 m (233 ft) tall and 9 m (30 ft) wide,[86] and contains thirty-three Raptor engines arranged in concentric rings.[100] The outermost ring of 20 engines are of the "Raptor Boost" configuration with gimbal actuators removed to save weight and a modified injector with reduced throttle performance in exchange for greater thrust.[99] At full power, all engines produce a collective 75.9 MN (17,100,000 lbf) of thrust.[101]

The booster's tanks can hold 3,600 t (7,900,000 lb) of propellant, consisting of 2,800 t (6,200,000 lb) of liquid oxygen and 800 t (1,800,000 lb) of liquid methane.[lower-alpha 4][102] However, current designs can only hold 3,400 t (7,500,000 lb) of propellant. The final design will have a dry mass between 160 t (350,000 lb) and 200 t (440,000 lb), with the tanks weighing 80 t (180,000 lb) and the interstage 20 t (44,000 lb).[84]

The booster is equipped with four electrically actuated grid fins, each with a mass of 3 t (6,600 lb). Adjacent pairs of grid fins are only spaced sixty degrees apart instead of being orthogonal (as is the case on Falcon 9) to provide more authority in the pitch axis. Also, unlike Falcon 9, the grid fins do not retract and remain extended during ascent.[84] The booster can be lifted through protruding hardpoints located between gridfins.[22] Above the grid fins is the vented interstage, which enables starship to use hot staging, which is when the second stage separates when some of the first stages engine are still firing. According to Elon Musk, this process may provide up to 10% increase in payload to orbit. During unpowered flight in the vacuum of space, control authority is provided by cold gas thrusters fed with residual ullage gas.

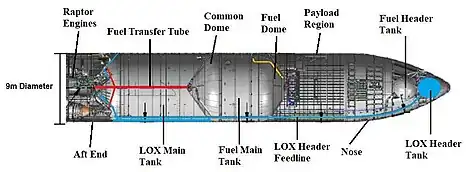

Starship spacecraft

The Starship spacecraft is 50 m (160 ft) tall, 9 m (30 ft) in diameter, and has 6 Raptor engines, 3 of which are optimized for use in outer space.[103][104] Future vehicles may have an additional 3 Raptor Vacuum engines for increased payload capacity. The vehicle's payload bay, measuring 17 m (56 ft) tall by 8 m (26 ft) in diameter, is the largest of any active or planned launch vehicle; its internal volume of 1,000 m3 (35,000 cu ft) is slightly larger than the ISS's pressurized volume.[105] SpaceX will also provide a 22 m (72 ft) tall payload bay configuration for even larger payloads.[106]Starship has a total propellant capacity of 1,200 t (2,600,000 lb)[107] across its main tanks and header tanks.[108] The header tanks are better insulated due to their position and are reserved for use to flip and land the spacecraft following reentry.[109] A set of reaction control thrusters, which use the pressure in the fuel tank, control attitude while in space.[110]

The spacecraft has four body flaps to control the spacecraft's orientation and help dissipate energy during atmospheric entry,[111] composed of two forward flaps and two aft flaps. According to SpaceX, the flaps replace the need for wings or tailplane, reduce the fuel needed for landing, and allow landing at destinations in the Solar System where runways don't exist (for example, Mars).[112]: 1 Under the forward flaps, hardpoints are used for lifting and catching the spacecraft via mechanical arms.[113] The flap's hinges are sealed in aero-covers because they would be easily damaged during reentry.[114]

Starship's heat shield, composed of thousands[115] of hexagonal black tiles that can withstand temperatures of 1,400 °C (2,600 °F),[116][117] is designed to be used many times without maintenance between flights.[118] The tiles are made of silica[119] and are attached with pins rather than glued,[117] with small gaps in between to allow for heat expansion.[114] Their hexagonal shape facilitate mass production[114] and prevent hot plasma from causing severe damage to the vehicle.

Variants

For satellite launch, Starship will have a large cargo door that will open to release payloads and close upon reentry instead of a more conventional jettisonable nose-cone fairing. Instead of a cleanroom, payloads are integrated directly into Starship's payload bay, which requires purging the payload bay with temperature-controlled ISO class 8 clean air.[106] To deploy Starlink satellites, the cargo door will be replaced with a slot and dispenser rack, whose mechanism has been compared to a Pez candy dispenser.[120]

Crewed Starship vehicles would replace the cargo bay with a pressurized crew section and have a life support system. For long-duration missions, such as crewed flights to Mars, SpaceX describes the interior as potentially including "private cabins, large communal areas, centralized storage, solar storm shelters, and a viewing gallery."[121] Starship's life support system is expected to recycle resources such as air and water from waste.[122]

Starship Human Landing System (HLS) is a crewed lunar lander variant of the Starship vehicle that is extensively modified for landing, operation, and takeoff from the lunar surface. It features modified landing legs, a body-mounted solar array, a set of thrusters mounted mid-body to assist with final landing and takeoff, two airlocks, and an elevator to lower crew and cargo onto the lunar surface. Starship HLS will be able to land more than 100 t (220,000 lb) of payload on the Moon per flight.[123]

Starship will be able to be refueled by docking with separately launched Starship propellant tanker spacecraft in orbit. Doing so would increase the spacecraft's mass capacity and allow it to reach higher-energy targets,[lower-alpha 5] such as geosynchronous orbit, the Moon, and Mars.[124] A Starship propellant depot could cache methane and oxygen on-orbit, and will be used by Starship HLS to replenish its fuel tanks.[125]

Mission profile

The payload is integrated into Starship at a separate facility and then rolled out to the spaceport.[102] After Super Heavy and Starship are stacked onto their launch mount by lifting from hardpoints, they are loaded with fuel via the quick disconnect arm and support.[22] Roughly four hundred truck deliveries are needed for one launch, although some commodities are provided on-site via an air separation unit.[102] Then, the arm and mount detach, all thirty-three engines of Super Heavy ignite, and the rocket lifts off.[22]

After two minutes,[126] at an altitude of 65 km (40 mi), Super Heavy cuts off 30 of its engines, leaving only three center ones running at 50% thrust. Then, the ship ignites its engines while still attached to the booster and separates. As the booster returns to the launch site via a controlled descent, it will be caught by a pair of mechanical arms.[127] After six minutes of flight, about 20 t (44,000 lb) of propellant remains inside the booster.[126][84]

Meanwhile, the Starship spacecraft accelerates to orbital velocity. Once in orbit, the spacecraft can be refueled by one or more tanker variant Starships, increasing the spacecraft's capacity.[128] Musk estimated in a tweet that 8 launches would be needed to completely refuel a Starship in low Earth orbit, having extrapolated this by using Starship's payload to orbit and combining it with how much fuel a fully fueled Starship contains.[129] To land on bodies without an atmosphere, such as the Moon, Starship will fire its engines and thrusters to slow down.[130] To land on bodies with an atmosphere such as the Earth and Mars, Starship first slows by entering the atmosphere via a heat shield.[88] The spacecraft then performs a "belly-flop" maneuver by diving back through the atmosphere body at a 60° angle to the ground,[12] and controls its fall using the four flaps.[26]

Shortly before landing, the Raptor engines fire,[26] using fuel from the header tanks,[131] causing the spacecraft to resume vertical orientation. At this stage, Raptor engines' gimbaling, throttle, and reaction control system's firing help to maneuver the craft.[26] A pseudospectral optimal control algorithm by the German Aerospace Center predicted that the landing flip would tilt up to 20° from the ground's perpendicular line, and the angle would be reduced to zero on touchdown.[132]: 10–12 Future Starships are envisioned to be caught by mechanical arms, like the booster.[22]

If Starship's rocket stages land on a pad, a mobile hydraulic lift moves them to a transporter vehicle. If the rocket stages land on a floating platform, they will be transported by a barge to a port and finally transported by road. The recovered Super Heavy and Starship will either be positioned on the launch mount for another launch or refurbished at a SpaceX facility.[102]: 22

Potential uses

Starship's reusability is expected to reduce launch costs, expanding space access to more payloads and entities.[133] Musk has predicted that a Starship orbital launch will eventually cost $1 million. Eurospace's director of research, Pierre Lionnet, however, stated that Starship's launch price would likely be higher because of the rocket's development cost.[134]

Crewed and cargo launches

Starship also plans to launch the second generation of SpaceX's Starlink satellites, which deliver global high-speed internet.[135] A space analyst at financial services company Morgan Stanley stated development of Starship and Starlink are intertwined, with Starship launch capacity enabling cheaper Starlink launches, and Starlink's profits financing Starship's development costs.[136]

As of 19 August 2022, the Superbird-9 communication satellite is Starship's first and only known contract for externally made commercial satellites. The satellite weighs 3 t (6,600 lb) dry mass, planned for 2024 launch to a geostationary orbit.[137] In the future, the spacecraft's crewed version could be used for space tourism—for example, the DearMoon project funded by Yusaku Maezawa.[138] Another example is the third flight of the Polaris program announced by Jared Isaacman.[139]

Farther in the future, Starship may host point-to-point flights (called "Earth to Earth" flights by SpaceX), traveling anywhere on Earth in under an hour.[140] SpaceX president and chief operating officer Gwynne Shotwell said point-to-point travel could become cost competitive with conventional business class flights.[141] John Logsdon, an academic on space policy and history, said point-to-point travel is unrealistic, as the craft would switch between weightlessness to 5 g of acceleration.[142] In January 2022, SpaceX was awarded a $102 million five-year contract to develop the Rocket Cargo program for the United States Space Force.[78]

Space exploration

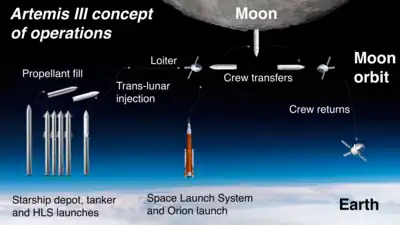

Starship's lunar lander Starship HLS has been chosen by NASA as the sole lunar lander for the Artemis 3 and Artemis 4 crewed missions, as part of the Artemis program.[143][144] The lander is accompanied by Starship tankers and propellant depots. The tankers transfer fuel to a depot until it is full, then the depot fuels Starship HLS. The lunar lander is thus endowed with enough thrust to achieve a lunar orbit. Then, the crews on board the Orion spacecraft are launched with the Space Launch System. Orion then docks with Starship HLS, and the crews transfer into the lander. After landing and returning, the lunar crews transfer back to Orion and return to Earth.[145]: 4, 5

Astronomers have called to consider Starship's larger mass to orbit and wider cargo bay for proposed space telescopes such as LUVOIR, and to develop larger telescopes to take advantage of these capabilities.[146][147] Starship's 9 meters fairing width could hold an 8 meters-wide large space telescope mirror in a single piece,[146] alleviating the need for complex origami deployments such as that of the JWST's 6.5m mirror which added cost and delays.[147]

The low launch cost could also allow probes to use heavier, more common, cheaper materials, for instance glass instead of beryllium for large telescope mirrors.[147][134] For instance at 5 tons, the JWST would have been only 10% of the mass deliverable by a Starship to the Sun-Earth L2 point, and therefore not a dominant design consideration.[147]

A refueled Starship could launch 100 ton observatories to the Moon, L2 Lagrange point and anywhere else in the solar system.[147] Starship might also launch probes orbiting Neptune or Io, or large sample-return missions.[128] Astrophysicists have noted Starship could deploy multiple antennae up to 30 meters in length, opening up radio astronomy to frequencies below 30MHz and wavelengths greater than 10m.[147] This would give the ability to study the Universe's dark ages, unfeasible on Earth due to the atmosphere and human radio background.[147]

Opinions differ on how Starship's low launch cost will affect the cost of space science. According to Waleed Abdalati, former NASA Chief Scientist, the low launch cost will cheapen satellite replacement and enable more ambitious missions for budget-limited programs.[148] According to Lionnet, low launch cost might not reduce the overall cost of a science mission significantly: of the Rosetta space probe and Philae lander's mission cost of $1.7 billion, the cost of launch (by the expendable Ariane 5) only made up ten percent.[148]

Space colonization

Starship is intended to be able to land crews on Mars.[149]: 120 The spacecraft is launched to low Earth orbit, and is then refueled by around five tanker spacecraft before heading to Mars.[150] After landing on Mars, the Sabatier reaction is used to synthesize liquid methane and liquid oxygen, Starship's fuel, in a power-to-gas plant. The plant's raw resources are Martian water and Martian carbon dioxide.[97] On Earth, similar technologies could be used to make carbon-neutral propellant for the rocket.[151]

SpaceX and Musk have stated their goal of colonizing Mars to ensure the long-term survival of humanity,[134][152] with an ambition of sending a thousand Starship spacecraft to Mars during a Mars launch window in a very far future.[153] Musk had maintained an interest in Mars colonization since 2001, when he joined the Mars Society and researched Mars-related space experiments before founding SpaceX in 2002.[154]: 99–100, 102, 112 Musk has made tentative estimates of Starship's Mars landing;[92] in March 2022, he gave a date of 2029 for the first crewed Mars landing.[155] SpaceX has not published technical plans about Starship's life support systems, radiation protection,[156] or in-orbit refueling.[150]

Facilities

Testing and manufacturing

Starbase consists of a manufacturing facility and launch site,[157] and is located at Boca Chica, Texas. Both facilities operate twenty-four hours a day.[93] A maximum of 450 full-time employees may be onsite.[102]: 28 The site is planned to consist of two launch sites, one payload processing facility, one seven-acre solar farm, and other facilities.[102]: 34–36 As of April 2022, the expansion plan's permit has been withdrawn by the United States Army Corps of Engineers, citing lack of information provided.[158] The company leases Starbase's land for the STARGATE research facility, owned by the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. It uses part of it for Starship development.[159]

At McGregor, Texas, the Rocket Development facility tests all Raptor engines. The facility has two main test stands: one horizontal stand for both engine types and one vertical stand for sea-level-optimized rocket engines. Other test stands are used for checking Starship's reaction control thrusters and Falcon's Merlin engines. The McGregor facility previously hosted test flights of landable first stages—Grasshopper and F9R Dev1. In the future, a nearby factory, which as of September 2021 was under construction, will make the new generation of sea-level Raptors while SpaceX's headquarters in California will continue building the Raptor Vacuum and test new designs.[160]

At Florida, a facility at Cocoa purifies silica for Starship heat-shield tiles, producing a slurry that is then shipped to a facility at Cape Canaveral. In the past, workers constructed the Starship Mk2 prototype in competition with Starbase's crews.[161] The Kennedy Space Center, also in Florida, is planned to host other Starship facilities, such as Starship launch sites at Launch Complex 39A, the planned Launch Complex 49, and a production facility at Roberts Road. This production facility is being expanded from "Hangar X", the Falcon rocket boosters' storage and maintenance facility. It will include a 30,000 m2 (320,000 sq ft) building, loading dock, and a place for constructing integration tower sections.[162]

Launch sites

Starbase is planned to host two launch sites, named Pad A and Pad B.[102]: 34 A launch site at Starbase has large facilities, such as a tank farm, an orbital launch mount, and an integration tower. Smaller facilities are present at the launch site: tanks surrounding the area containing methane, oxygen, nitrogen, helium, hydraulic fluid, etc.;[102]: 161 subcoolers near the tank farm cool propellant using liquid nitrogen; and various pipes are installed at large facilities.[22] Each tank farm consists of eight tanks, enough to support one orbital launch. The current launch mount on Pad A has a water sound suppression system, twenty clamps holding the booster, and a quick disconnect mount providing liquid fuel and electricity to the Super Heavy booster before it lifts off.[22]

The integration tower or launch tower consists of steel truss sections, a lightning rod on top,[163] and a pair of mechanical arms that can lift, catch and recover the booster.[22] The decision was made to enable flights and reduce the rocket's mass and part count.[36]: 2 The mechanical arms are attached to a carriage and controlled by a pulley at the top of the tower. The pulley is linked to a winch and spool at the base of the tower using a cable. Using the winch, the carriage, and mechanical arms can move vertically, with support from bearings attached at the sides of the carriage. A linear hydraulic actuator moves the arms horizontally. Tracks are mounted on top of arms, which are used to position the booster or spacecraft. The tower is mounted with a quick disconnect arm extending to and contracting from the Starship spacecraft; its functions are similar to the quick disconnect mount that powers the booster.[22]

Since 2021,[164] the company is constructing a second Starship launch pad in Cape Canaveral, Florida, in Kennedy Space Center's Launch Complex 39A,[162] which is currently used to launch Crew Dragon capsules to the International Space Station.[164] SpaceX plans to make a separate pad at 39A's north, named Launch Complex 49.[162] Because of Launch Complex 39A's Crew Dragon launches, the company is studying how to strengthen the pad against the possibility of a Starship explosion and proposed to retrofit Cape Canaveral Space Launch Complex 40 instead.[164] The towers and mechanical arms at the Florida launch sites should be similar to the one at Starbase, with improvements gained from the experience at Boca Chica.[162]

Phobos and Deimos were the names of two Starship offshore launch platforms, both in renovation as of March 2022.[165] Before being purchased from Valaris Limited in June 2020,[166] they were nearly identical oil platforms named Valaris 8501 and Valaris 8500. However, following further analysis from SpaceX, it has been announced that the offshore platforms were not suitable for Starship launches.[167] The platforms were sold earlier in 2023.[167]

Community reception

.jpg.webp)

Outside the space community, reception to Starship's development among nearby locales has been mixed, especially from cities close to the Starbase spaceport. Proponents of SpaceX's arrival said the company would provide money, education, and job opportunities to the country's poorest areas. Fewer than one-fifth of those 25 or older in the Rio Grande Valley have a bachelor's degree, in comparison to the national average of one-third.[168] The local government has stated that the company boosted the local economy by hiring residents and investing, aiding the three-tenths of the population who live in poverty.[169]

Activist Elias Cantu of the League of United Latin American Citizens said the company encourages Brownsville's gentrification, with an ever-increasing property valuation.[169] Even though Starbase had originally planned to launch Falcon rockets when the original environmental assessment was completed in 2014,[170] the site in 2019 was subsequently used to develop Starship, ultimately requiring a revised environmental assessment.[171] Some of the tests have ended in large explosions, causing major disruption to residents and wildlife reserves. The Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe and environmental activists also allege that SpaceX have overpoliced the area, disrupting indigenous ceremonies and local fishing.[172]

Starship's first integrated spaceflight attempt blasted large amounts of sand in the air, reaching communities within a 10-km (6-mile) radius.[173][174] A small brushfire on nearby state parkland also occurred.[175] There were concerns about the launch's impact on the health of both human residents and endangered species because of the sand blast, which was rumored to be concrete and silt particulate matter before analyses ruled against it.[173][174]

The impact of the launch led to a lawsuit against the FAA, later joined by SpaceX, from four environmental groups and the Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe.[176][177][178] The disruption to residents is compounded by SpaceX's frequent closures of the road to the beach for vehicle testing.[171] Some residents have moved away or requested financial reparations from the company.[169]

Notes

- Source states cost is the amount invested by SpaceX and doesn't state whether it includes NASA investment

- See Comparison of orbital launch systems for more information

- Super Heavy dry mass: 160 t (350,000 lb) – 200 t (440,000 lb); Starship dry mass: <100 t (220,000 lb); Super Heavy propellant mass: 3,600 t (7,900,000 lb);[84] Starship propellant mass: 1,200 t (2,600,000 lb).[85] The total of these masses is about 5,000 t (11,000,000 lb).

- 78% of 3,600 t (7,900,000 lb)[84] is 2,800 t (6,200,000 lb) of liquid oxygen.

- Synonymous with increasing the delta-v budget of the spacecraft

See also

- Comparison of orbital launch systems

- Comparison of orbital launcher families

- Long March 9, a super-heavy-lift launch vehicle developed by China, designed to be reusable and close to Starship in tons to orbit

- SpaceX reusable launch system development program

References

- Sheetz, Micheal (22 May 2023). "SpaceX set to join FAA to fight environmental lawsuit that could delay Starship work". SpaceX set to join FAA to fight environmental lawsuit that could delay Starship work. CNBC. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- Wall, Mike (21 April 2023). "What's next for SpaceX's Starship after its historic flight test?". Space.com. Archived from the original on 27 April 2023. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- Bergin, Chris (27 September 2016). "SpaceX reveals ITS Mars game changer via colonization plan". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 28 September 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- "Making Humans a Multiplanetary Species" (PDF). SpaceX. 27 September 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 November 2017. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- Richardson, Derek (27 September 2016). "Elon Musk Shows Off Interplanetary Transport System". Spaceflight Insider. Archived from the original on 1 October 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- Boyle, Alan (19 November 2018). "Goodbye, BFR … hello, Starship: Elon Musk gives a classic name to his Mars spaceship". GeekWire. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

Starship is the spaceship/upper stage & Super Heavy is the rocket booster needed to escape Earth's deep gravity well (not needed for other planets or moons)

- "Starship". SpaceX. Archived from the original on 30 September 2019. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- "Starship Users Guide, Revision 1.0, March 2020" (PDF). SpaceX. March 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 April 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

SpaceX's Starship system represents a fully reusable transportation system designed to service Earth orbit needs as well as missions to the Moon and Mars. This two-stage vehicle – composed of the Super Heavy rocket (booster) and Starship (spacecraft)

- Berger, Eric (5 March 2020). "Inside Elon Musk's plan to build one Starship a week and settle Mars". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

Musk tackles the hardest engineering problems first. For Mars, there will be so many logistical things to make it all work, from power on the surface to scratching out a living to adapting to its extreme climate. But Musk believes that the initial, hardest step is building a reusable, orbital Starship to get people and tons of stuff to Mars. So he is focused on that.

- Berger, Eric (29 September 2019). "Elon Musk, Man of Steel, reveals his stainless Starship". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 28 December 2019. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Ryan, Jackson (29 September 2019). "Elon Musk says SpaceX Starship rocket could reach orbit within 6 months". CNET. Archived from the original on 15 December 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- Chang, Kenneth (29 September 2019). "SpaceX Unveils Silvery Vision to Mars: 'It's an I.C.B.M. That Lands'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- D'Agostino, Ryan (22 January 2019). "Elon Musk: Why I'm Building the Starship out of Stainless Steel". popularmechanics.com. Popular Mechanics. Archived from the original on 22 January 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- Ralph, Eric (25 July 2019). "SpaceX CEO Elon Musk hints that Starship's 'sweating' metal heat shield is no more".

- Musk, Elon [@elonmusk] (6 August 2021). "@NASASpaceflight @BBCAmos Over time, we might get orbital payload up to ~150 tons with full reusabity. If Starship then launched as an expendable, payload would be ~250 tons. What isn't obvious from this chart is that Starship/Super Heavy is much denser than Saturn V." (Tweet). Archived from the original on 14 August 2021. Retrieved 22 August 2021 – via Twitter.

- Sheetz, Michael (1 September 2020). "Elon Musk says SpaceX's Starship rocket will launch "hundreds of missions" before flying people". CNBC. Archived from the original on 2 September 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- Foust, Jeff (15 April 2021). "SpaceX adds to latest funding round". SpaceNews. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- Grush, Loren (20 November 2019). "SpaceX's prototype Starship rocket partially bursts during testing in Texas". The Verge. Archived from the original on 14 November 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- Bergeron, Julia (6 April 2021). "New permits shed light on activity at SpaceX's Cidco and Roberts Road facilities". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- Berger, Eric (21 February 2020). "SpaceX pushing iterative design process, accepting failure to go fast". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 25 December 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- Kanayama, Lee; Beil, Adrian (28 August 2021). "SpaceX continues forward progress with Starship on Starhopper anniversary". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- Weber, Ryan (31 October 2021). "Major elements of Starship Orbital Launch Pad in place as launch readiness draws nearer". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 5 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- Mack, Eric (4 August 2020). "SpaceX Starship prototype takes big step toward Mars with first tiny 'hop'". CNET. Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- Sheetz, Michael (3 September 2020). "SpaceX launches and lands another Starship prototype, the second flight test in under a month". CNBC. Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- Kooser, Amanda (26 September 2020). "Watch SpaceX fire up Starship's furious new Raptor Vacuum engine". CNET. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- Wattles, Jackie (10 December 2020). "Space X's Mars prototype rocket exploded yesterday. Here's what happened on the flight". CNN. Archived from the original on 10 December 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- Roulette, Joey (15 June 2021). "SpaceX ignored last-minute warnings from the FAA before December Starship launch". The Verge. Archived from the original on 6 October 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- Mack, Eric (2 February 2021). "SpaceX Starship SN9 flies high, explodes on landing just like SN8". CNET. Archived from the original on 18 September 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- Chang, Kenneth (3 March 2021). "SpaceX Mars Rocket Prototype Explodes, but This Time It Lands First". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- Foust, Jeff (5 May 2021). "Starship survives test flight". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 22 June 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- Mack, Eric (30 March 2021). "SpaceX Starship SN11 test flight flies high and explodes in the fog". CNET. Archived from the original on 20 December 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

- Foust, Jeff (6 April 2021). "Engine explosion blamed for latest Starship crash". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 29 September 2021. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- Berger, Eric (8 March 2021). "SpaceX reveals the great extent of its starport plans in South Texas". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- Keates, Nancy; Maremont, Mark (7 May 2021). "Elon Musk's SpaceX Is Buying Up a Texas Village. Homeowners Cry Foul". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- Mack, Eric (7 May 2021). "SpaceX's Mars prototype rocket, Starship SN15, might fly again soon". CNET. Archived from the original on 20 December 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

- "Starbase Overview" (PDF). SpaceX. 29 March 2023. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- Berger, Eric (23 July 2021). "Rocket Report: Super Heavy lights up, China tries to recover a fairing". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 12 August 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- Berger, Eric (14 July 2021). "SpaceX will soon fire up its massive Super Heavy booster for the first time". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 8 January 2022. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- Bergin, Chris (5 May 2022). "One year since SN15, Starbase lays groundwork for orbital attempt". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 7 June 2022. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- Sheetz, Michael (6 August 2021). "Musk: 'Dream come true' to see fully stacked SpaceX Starship rocket during prep for orbital launch". CNBC. Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- Costa, Jason (15 December 2021). "NASA Conducts Environmental Assessment, Practices Responsible Growth". NASA (Press release). Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- Sesnic, Trevor (14 July 2022). "Raptor 1 vs Raptor 2: What did SpaceX change?". The Everyday Astronaut. Archived from the original on 19 August 2022. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- Mooney, Justin; Bergin, Chris (11 February 2022). "Musk outlines Starship progress towards self-sustaining Mars city". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 10 March 2022. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- Chang, Kenneth (13 June 2022). "SpaceX Wins Environmental Approval for Launch of Mars Rocket". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 June 2022. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- Dvorsky, George (10 August 2022). "SpaceX Performs Limited Static Fire Test of Starship Booster, Avoids Explosion". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- Kshatriya, Amit; Kirasich, Mark (31 October 2022). "Artemis I – IV Mission Overview / Status" (PDF). NASA. Human Exploration and Operations Committee of the NASA Advisory Council. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 November 2022. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- Iemole, Anthony (7 December 2022). "Boosters 7 and 9 in dual flow toward Starbase test milestones". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- Foust, Jeff (24 January 2023). "SpaceX completes Starship wet dress rehearsal". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- Wall, Mike (17 April 2023). "SpaceX scrubs 1st space launch of giant Starship rocket due to fueling issue". Space.com. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- Wattles, Jackie; Strickland, Ashley (20 April 2023). "SpaceX's Starship rocket lifts off for inaugural test flight, but explodes midair". CNN. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- Bergin, Chris (3 May 2023). "Elon Musk pushes for orbital goal following data gathering objectives during Starship debut". NASASpaceFlight.com. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- Malik, Tariq; published, Mike Wall (20 April 2023). "SpaceX's 1st Starship launches on epic test flight, explodes in 'rapid unscheduled disassembly'". Space.com. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

- "SpaceX". SpaceX. Archived from the original on 14 April 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- Klotz, Irene (1 May 2023). "Engine Issue Felled SpaceX First Super Heavy | Aviation Week Network". Aviation Week Network. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- Salinas, Sara (20 April 2023). "SpaceX launches towering Starship rocket but suffers mid-flight failure". CNBC. Archived from the original on 20 April 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- Berger, Eric (10 April 2023). "SpaceX's Starship vehicle is ready to fly, just waiting for a launch license". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 11 April 2023. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- "Starship Orbital – First Flight FCC Exhibit". SpaceX (PDF). 13 May 2021. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- Kolodny, Lora (28 July 2023). "SpaceX hasn't obtained environmental permits for 'flame deflector' system it's testing in Texas". CNBC. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- Romera, Alejandro Alcantarilla (6 September 2023). "SpaceX stacks Ship 25 and Booster 9, prepares for flight". NASASpaceFlight.com. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- Kolodny, Lora (8 September 2023). "FAA orders Musk's SpaceX to take 63 corrective actions on Starship, keeps rocket grounded". CNBC. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- Chang, Kenneth (8 September 2023). "F.A.A. Spells Out Needed Fixes for SpaceX's Starship Rocket". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- Foust, Jeff (8 September 2023). "FAA closes Starship mishap investigation, directs 63 corrective actions for SpaceX". SpaceNews. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- Wall, Mike (8 September 2023). "FAA closes investigation of SpaceX's Starship rocket launch mishap, 63 fixes needed". Space.com.

- Shepardson, David (13 September 2023). "US could advance SpaceX license as soon as October after rocket exploded in April". Reuters. Retrieved 14 September 2023.

- Mack, Eric (14 September 2023). "Giant SpaceX Starship Could Fly Again in October". CNET. Retrieved 14 September 2023.

- Dvorsky, George (19 September 2023). "Environmental Scrutiny May Push SpaceX's Second Starship Launch to Next Year". Gizmodo. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- Grush, Loren; Hull, Dana (18 September 2023). "SpaceX's Starship Still Needs Wildlife Agency Review to Resume Launch". BNN Bloomberg. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- Robinson-Smith, Will (18 October 2023). "SpaceX battles regulatory process that could hold up Starship test flight for months". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- Eric Berger (17 October 2023). "Citing slow Starship reviews, SpaceX urges FAA to double licensing staff". Ars Technica. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- LabPadre Space (19 October 2023). "LabPadre Space on X: "Fish and Wildlife Service is surveying the area around the Launch Site. Come tune in and watch live"". Twitter. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- Davenport, Christian (17 October 2023). "SpaceX to the FAA: The industry needs you to move faster". The Washington Post. Retrieved 20 October 2023.

- Brown, Katherine (16 April 2021). "NASA Picks SpaceX to Land Next Americans on Moon". NASA. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- "SpaceX Awarded $1.15 Billion Contract to Build NASA's Second Lunar Lander". Yahoo News. 17 November 2022. Archived from the original on 23 November 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- Roulette, Joey (30 April 2021). "NASA suspends SpaceX's $2.9 billion moon lander contract after rivals protest". The Verge. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 26 December 2021.

- Pruitt-Young, Sharon (17 August 2021). "Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin Sues NASA Over A Lunar Lander Contract Given To Rival SpaceX". NPR. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- Sheetz, Michael (4 November 2021). "Bezos' Blue Origin loses NASA lawsuit over SpaceX $2.9 billion lunar lander contract". CNBC. Archived from the original on 4 January 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- O’Shea, Claire (19 May 2023). "NASA Selects Blue Origin as Second Artemis Lunar Lander Provider". NASA. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

- Erwin, Sandra (19 January 2022). "SpaceX wins $102 million Air Force contract to demonstrate technologies for point-to-point space transportation". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 29 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- Foust, Jeff (26 May 2023). "SpaceX investment in Starship approaches $5 billion". SpaceNews. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- Berger, Eric (29 September 2019). "Elon Musk, Man of Steel, reveals his stainless Starship". Ars Technica. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Kolodny, Lora; Sheetz, Michael (22 May 2023). "SpaceX set to join FAA to fight environmental lawsuit that could delay Starship work". CNBC. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- Sheetz, Michael (30 April 2023). "SpaceX to spend about $2 billion on Starship this year, as Elon Musk pushes to reach orbit". CNBC. Archived from the original on 30 April 2023. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- Maidenberg, Micah (30 April 2023). "Elon Musk Expects SpaceX to Spend Around $2 Billion on Starship Rocket This Year". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- Sesnic, Trevor (11 August 2021). "Starbase Tour and Interview with Elon Musk". The Everyday Astronaut (Interview). Archived from the original on 12 August 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- Lawler, Richard (29 September 2019). "SpaceX's plan for in-orbit Starship refueling: a second Starship". Engadget. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

- Dvorsky, George (6 August 2021). "SpaceX Starship Stacking Produces the Tallest Rocket Ever Built". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- Foust, Jeff (24 June 2023). "SpaceX changing Starship stage separation ahead of next launch". SpaceNews. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- Inman, Jennifer Ann; Horvath, Thomas J.; Scott, Carey Fulton (24 August 2021). SCIFLI Starship Reentry Observation (SSRO) ACO (SpaceX Starship). Game Changing Development Annual Program Review 2021. NASA. Archived from the original on 11 October 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- "Starship". SpaceX. 5 February 2023. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

Starship will be the world's most powerful launch vehicle ever developed, with the ability to carry up to 149 metric tonnes to Earth orbit reusable, and up to 250 metric tonnes expendable.

- Amos, Jonathan (6 August 2021). "Biggest ever rocket is assembled briefly in Texas". BBC News. Archived from the original on 11 August 2021. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- Ryan, Jackson (21 October 2021). "SpaceX Starship Raptor vacuum engine fired for the first time". CNET. Archived from the original on 9 June 2022. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- Chang, Kenneth (28 September 2019). "Elon Musk Sets Out SpaceX Starship's Ambitious Launch Timeline". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- Berger, Eric (5 March 2020). "Inside Elon Musk's plan to build one Starship a week—and settle Mars". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- Berger, Eric (8 June 2021). "Relativity has a bold plan to take on SpaceX, and investors are buying it". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- Berger, Eric (27 July 2021). "Blue Origin has a secret project named "Jarvis" to compete with SpaceX". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 30 July 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- O'Callaghan, Jonathan (31 July 2019). "The wild physics of Elon Musk's methane-guzzling super-rocket". Wired UK. Archived from the original on 22 February 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- Sommerlad, Joe (28 May 2021). "Elon Musk reveals Starship progress ahead of first orbital flight of Mars-bound craft". The Independent. Archived from the original on 23 August 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- "The rockets NASA and SpaceX plan to send to the moon". The Washington Post.

- Bergin, Chris (19 July 2021). "Super Heavy Booster 3 fires up for the first time". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 12 August 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- Bergin, Chris (9 June 2022). "Starbase orbital duo preps for Static Fire campaign – KSC Starship Progress". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 19 June 2022. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- "Starship official website". SpaceX. Archived from the original on 3 July 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- "Final Programmatic Environmental Assessment for the SpaceX Starship/Super Heavy Launch Vehicle Program at the SpaceX Boca Chica Launch Site in Cameron County, Texas" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration and SpaceX. June 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 June 2022. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- Dvorsky, George (6 August 2021). "SpaceX Starship Stacking Produces the Tallest Rocket Ever Built". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- Petrova, Magdalena (13 March 2022). "Why Starship is the holy grail for SpaceX". CNBC. Archived from the original on 28 May 2022. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- Garcia, Mark (5 November 2021). "International Space Station Facts and Figures". NASA. Archived from the original on 6 June 2022. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- "Starship Users Guide" (PDF). SpaceX. March 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 August 2021. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- Lawler, Richard (29 September 2019). "SpaceX's plan for in-orbit Starship refueling: a second Starship". Engadget. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- Sheetz, Michael (30 March 2021). "Watch SpaceX's launch and attempted landing of Starship prototype rocket SN11". CNBC. Archived from the original on 30 March 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

- Kooser, Amanda (1 October 2019). "Elon Musk video lets us peep inside SpaceX Starship". CNET. Archived from the original on 10 June 2022. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- Wattles, Jackie (10 December 2020). "Space X's Mars prototype rocket exploded yesterday. Here's what happened on the flight". CNN. Archived from the original on 10 December 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- Sheetz, Michael (3 March 2021). "SpaceX Starship prototype rocket explodes after successful landing in high-altitude flight test". CNBC. Archived from the original on 20 December 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "Starbase Overview" (PDF). SpaceX. 29 March 2023. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- Weber, Ryan (31 October 2021). "Major elements of Starship Orbital Launch Pad in place as launch readiness draws nearer". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 5 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- Sesnic, Trevor (11 August 2021). "Starbase Tour and Interview with Elon Musk". The Everyday Astronaut (Interview). Archived from the original on 12 August 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- Sheetz, Michael (6 August 2021). "Musk: 'Dream come true' to see fully stacked SpaceX Starship rocket during prep for orbital launch". CNBC. Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- Torbet, Georgina (29 March 2019). "SpaceX's Hexagon Heat Shield Tiles Take on an Industrial Flamethrower". Digital Trends. Archived from the original on 6 January 2022. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- Reichhardt, Tony (14 December 2021). "Marsliner". Air & Space/Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 6 May 2022. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- Inman, Jennifer Ann; Horvath, Thomas J.; Scott, Carey Fulton (24 August 2021). SCIFLI Starship Reentry Observation (SSRO) ACO (SpaceX Starship). Game Changing Development Annual Program Review 2021. NASA. Archived from the original on 11 October 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- Bergeron, Julia (6 April 2021). "New permits shed light on the activity at SpaceX's Cidco and Roberts Road facilities". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- Dvorsky, George (6 June 2022). "Musk's Megarocket Will Deploy Starlink Satellites Like a Pez Dispenser". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 9 June 2022. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- Grush, Loren (4 October 2019). "Elon Musk's future Starship updates could use more details on human health and survival". The Verge. Archived from the original on 8 October 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- Burghardt, Thomas (20 April 2021). "After NASA taps SpaceX's Starship for first Artemis landings, the agency looks to on-ramp future vehicles". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- Scoles, Sarah (12 August 2022). "Prime mover". Science. 377 (6607): 702–705. Bibcode:2022Sci...377..702S. doi:10.1126/science.ade2873. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 35951703. S2CID 240464593. Archived from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- "NASA's management of the Artemis missions" (PDF). NASA Office of Inspector General. 15 November 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 November 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- Moon, Mariella (11 February 2022). "SpaceX shows what a Starship launch would look like". Engadget. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- Cuthbertson, Anthony (30 August 2021). "SpaceX will use 'robot chopsticks' to catch massive rocket, Elon Musk says". The Independent. Archived from the original on 22 June 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- O'Callaghan, Jonathan (7 December 2021). "How SpaceX's massive Starship rocket might unlock the solar system—and beyond". MIT Technology Review. Archived from the original on 8 December 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- Williams, Matt (18 August 2021). "Musk Says That Refueling Starship for Lunar Landings Will Take 8 Launches (Maybe 4)".

- Foust, Jeff (6 January 2021). "SpaceX, Blue Origin, and Dynetics Compete to Build the Next Moon Lander". IEEE Spectrum. Archived from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- Kooser, Amanda (1 October 2019). "Elon Musk video lets us peep inside SpaceX Starship". CNET. Archived from the original on 10 June 2022. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- Sagliano, Marco; Seelbinder, David; Theil, Stephan (25 June 2021). SPARTAN: Rapid Trajectory Analysis via Pseudospectral Methods (PDF). 8th International Conference on Astrodynamics Tools and Techniques. German Aerospace Center. Bremen, Germany. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 December 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- Mann, Adam (20 May 2020). "SpaceX now dominates rocket flight, bringing significant benefits—and risks—to NASA". Science. doi:10.1126/science.abc9093. S2CID 219490398. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- Scoles, Sarah (12 August 2022). "Prime mover". Science. 377 (6607): 702–705. Bibcode:2022Sci...377..702S. doi:10.1126/science.ade2873. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 35951703. S2CID 240464593. Archived from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- Sheetz, Michael (19 August 2021). "SpaceX adding capabilities to Starlink internet satellites, plans to launch them with Starship". CNBC. Archived from the original on 7 January 2022. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- Sheetz, Michael (19 October 2021). "Morgan Stanley says SpaceX's Starship may 'transform investor expectations' about space". CNBC. Archived from the original on 20 December 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

- Rainbow, Jason (18 August 2022). "Sky Perfect JSAT picks SpaceX's Starship for 2024 satellite launch". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 19 August 2022. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- Ryan, Jackson (15 July 2021). "SpaceX moon mission billionaire reveals who might get a ticket to ride Starship". CNET. Archived from the original on 13 January 2022. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- Sheetz, Michael (14 February 2022). "Billionaire astronaut Jared Isaacman buys more private SpaceX flights, including one on Starship". CNBC. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- Sheetz, Michael (4 June 2021). "The Pentagon wants to use private rockets like SpaceX's Starship to deliver cargo around the world". CNBC. Archived from the original on 1 September 2021. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- Sheetz, Michael (18 March 2019). "Super fast travel using outer space could be US$20 billion market, disrupting airlines, UBS predicts". CNBC. Archived from the original on 29 October 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- Ferris, Robert (29 September 2017). "Space expert calls Elon Musk's plan to fly people from New York to Shanghai in 39 minutes 'extremely unrealistic'". CNBC. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- Burghardt, Thomas (20 April 2021). "After NASA taps SpaceX's Starship for first Artemis landings, the agency looks to on-ramp future vehicles". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- Dodson, Gerelle (15 November 2022). "NASA Awards SpaceX Second Contract Option for Artemis Moon Landing". NASA. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- NASA's management of the Artemis missions (PDF) (Report). NASA Office of Inspector General. 15 November 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 November 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- Clark, Stephen (18 October 2023). "Astronomers say new telescopes should take advantage of "Starship paradigm"". Ars Technica. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- "Accelerating astrophysics with the SpaceX Starship". pubs.aip.org. Archived from the original on 21 October 2023. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- Bender, Maddie (16 September 2021). "SpaceX's Starship Could Rocket-Boost Research in Space". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 26 October 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- Goldsmith, Donald; Rees, Martin J. (19 April 2022). The End of Astronauts: Why Robots Are the Future of Exploration. Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-25772-6. OCLC 1266218790.

- Pearson, Ben (3 June 2019). "SpaceX beginning to tackle some of the big challenges for a Mars journey". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 11 October 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- Killelea, Eric (16 December 2021). "Musk looks to Earth's atmosphere as source of rocket fuel". San Antonio Express-News. Archived from the original on 20 December 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- Chang, Kenneth (27 September 2016). "Elon Musk's Plan: Get Humans to Mars, and Beyond". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 September 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- Kooser, Amanda (16 January 2020). "Elon Musk breaks down the Starship numbers for a million-person SpaceX Mars colony". CNET. Archived from the original on 7 February 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- Vance, Ashlee (2015). Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic Future. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-230123-9. OCLC 881436803.

- Torchinsky, Rina (17 March 2022). "Elon Musk hints at a crewed mission to Mars in 2029". NPR. Archived from the original on 8 June 2022. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- Grush, Loren (4 October 2019). "Elon Musk's future Starship updates could use more details on human health and survival". The Verge. Archived from the original on 8 October 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- Berger, Eric (2 July 2021). "Rocket Report: Super Heavy rolls to launch site, Funk will get to fly". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 6 October 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- Grush, Loren (6 April 2022). "Army Corps of Engineers closes SpaceX Starbase permit application citing lack of information". The Verge. Archived from the original on 15 June 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- "STARGATE – Spacecraft Tracking and Astronomical Research into Gigahertz Astrophysical Transient Emission". University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. Archived from the original on 5 August 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- Davenport, Justin (16 September 2021). "New Raptor Factory under construction at SpaceX McGregor amid continued engine testing". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 22 October 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- Bergeron, Julia (6 April 2021). "New permits shed light on the activity at SpaceX's Cidco and Roberts Road facilities". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- Bergin, Chris (22 February 2022). "Focus on Florida – SpaceX lays the groundwork for East Coast Starship sites". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2022. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- Berger, Eric (16 April 2021). "Rocket Report: SpaceX to build huge launch tower, Branson sells Virgin stock". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- Roulette, Joey (13 June 2022). "SpaceX faces NASA hurdle for Starship backup launch pad". Reuters. Archived from the original on 22 June 2022. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- Bergin, Chris (6 March 2022). "Frosty Texas vehicles and groundwork in Florida ahead of Starship evolution". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 17 March 2022. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- Sheetz, Michael (19 January 2021). "SpaceX bought two former Valaris oil rigs to build floating launchpads for its Starship rocket". CNBC. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- Foust, Jeff (14 February 2023). "SpaceX drops plans to convert oil rigs into launch platforms". SpaceNews. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- Fouriezos, Nick (9 March 2022). "SpaceX launches rockets from one of America's poorest areas. Will Elon Musk bring prosperity?". USA Today. Archived from the original on 10 March 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- Sandoval, Edgar; Webner, Richard (24 May 2021). "A Serene Shore Resort, Except for the SpaceX 'Ball of Fire'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 April 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- Klotz, Irene (11 July 2014). "FAA Ruling Clears Path for SpaceX Launch site in Texas". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 17 July 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- Kramer, Anna (7 September 2021). "SpaceX's launch site may be a threat to the environment". Protocol.com. Archived from the original on 1 December 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ""Colonizing Our Community": Elon Musk's SpaceX Rocket Explodes in Texas as Feds OK New LNG Projects". Democracy Now!. 21 April 2023. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- Kolodny, Lora (24 April 2023). "SpaceX Starship explosion spread particulate matter for miles". CNBC. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- Leinfelder, Andrea (2 August 2023). "SpaceX Starship sprinkled South Texas with mystery material. Here's what it was". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- Grush, Loren; Hull, Dana (26 April 2023). "SpaceX's Starship Launch Sparked Fire on State Park Land". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- Center for Biological Diversity et al. v. Federal Aviation Administration (D.C. Cir. 2023).Text

- Gorman, Steve (1 May 2023). "Environmentalists sue FAA over SpaceX launch license for Texas". Reuters. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- Killelea, Eric (23 May 2023). "SpaceX joins FAA as defendant in lawsuit over private space company's launch from South Texas". San Antonio Express-News. Retrieved 29 June 2023.

External links

- Official website

- Programmatic Environmental Assessment by the Federal Aviation Administration

- Starship of SpaceX on eoPortal directory, administered by the European Space Agency

- Tim Dodd's Starship interviews with Elon Musk on YouTube:

- A conversation with Elon Musk about Starship, 2019

- Starbase and Starship tour, 2021: part 1, part 2, and part 3

- Launch tower and Raptor engine tour, 2022: overview, launch infrastructure, Raptor engine

.jpg.webp)