Stavronikita

Stavronikita Monastery (Greek: Μονή Σταυρονικήτα, Moní Stavronikíta) is an Eastern Orthodox monastery at the monastic state of Mount Athos in Greece, dedicated to Saint Nicholas. It is built on top of a rock near the sea near the middle of the eastern shore of the Athonite Peninsula, located between the monasteries of Iviron and Pantokratoros. The site where the monastery is built was first used by Athonite monks as early as the 10th century. Stavronikita was the last to be officially consecrated as an Athonite monastery in 1536 and ranks fifteenth in the hierarchy of the Athonite monasteries. It currently has 30 to 40 monks.

Σταυρονικήτα | |

Southeast view of the monastery | |

Location within Mount Athos | |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Full name | Holy Monastery of Stavronikita |

| Order | Ecumenical Patriarchate |

| Dedicated to | Saint Nicholas |

| Diocese | Mount Athos |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | Nicetas (or Stavronicetas) Nicephorus |

| Prior | Archimandrite Elder Tykhon |

| Site | |

| Location | Mount Athos, Greece |

| Coordinates | 40°16′04.74″N 24°16′36.24″E |

| Public access | Men only |

Name

There are various conflicting traditions and stories regarding the monastery's name. According to one Athonite tradition, the name is a combination of the names of two monks, Stavros and Nikitas, that used to live in two cells at the site before the monastery was built. Another tradition recounts of a Byzantine army officer serving under the Byzantine Emperor John I Tzimiskes, named Niceforus Stavronikitas that built the monastery and named it after himself. Yet a third tradition attributes the foundation of the monastery to a patrician by the name Nikitas. The patrician's name day according to the Eastern Orthodox calendar of saints is celebrated the day after the Feast of the Cross. Hence according to this tale the monastery got its name by combination of the patrician's name with the word "Stavros" (the Greek word for cross).

Apart from the traditional name, in some old documents the monastery is referred to as "Monastery of the Theotokos", which implies that the monastery was initially dedicated to the Theotokos. A more often encountered alternative name is "Monastery of Stravonikita" which is a corruption of the original name.

History

The many conflicting tales of the monastery's name hint to the obscurity of its historical origins. In a document by the Protos Nikiforos dating back to 1012 there is the signature of a monk who signs as "Nikiforos monk from Stravonikita" (Greek: Νικηφόρος μοναχός ο του Στραβωνικήτα), while in a 1016 document, the same monk signs as "from Stavronikita" (Greek: του Σταυρονικήτα). This alludes to the existence of a Stavronikita monastery as late as the first half of the 11th century. According to archaeologist Sotiris Kadas this means that the Stavronikita monastery was one of the monasteries that were founded or built during the first years of organized monastic life on Mount Athos.[1]

This early part of the monastery's history ended approximately during the first half of the 13th century when the monastery was deserted due to constant pirate raids as well as due to the tremendous impact caused by the Fourth Crusade to the whole of the Byzantine Empire. The deserted monastery came initially under the jurisdiction of the Protos and later under the jurisdiction of Koutloumousiou monastery and later Philotheou monastery and functioned as a skete. In 1533, The monks of Philotheou sold Stavronikita to the abbot of a Thesprotian monastery, Gregorios Giromeriatis (Greek: Γρηγόριος Γηρομερειάτης). By the end of the 15th century, the Russian pilgrim Isaiah confirms that, the monastery was Greek.[2]

In 1536, a patriarchical edict by Patriarch Jeremias I reinstated Stavronikita's status as one of the monasteries of Athos, bringing their total number to 20. Therefore, Stavronikita became the last officially consecrated monastery of Athos and is usually referred as the last monastery to be added to the athonite hierarchy.

Gregorios Giromeriatis eventually left his monastery in Thesprotia and permanently settled in Stavronikita. In subsequent years he expended great efforts to rebuild and expand the monastery. He built a surrounding wall, many cells, as well as the monastery's catholicon. After the death of Gregorios in 1540, the renovation was continued by Patriarch Jeremias himself out of love and respect for Gregorios. An extraordinary feature of the monastery during this era is the fact that while most of the athonite monasteries had already largely adopted the so-called "idiorythmic" lifestyle (a semi-eremitic variant of Christian monasticism), Stavronikita was founded and continued to function long after as on the principles of cenobitic monasticism.

The subsequent history of the monastery was marked by the fact that it always remained small in comparison to other athonite monasteries, both in property and in number of monks. Despite the repeated aid by the athonite community as well as by important benefactors, such as archon Servopoulos in 1612, the monk Markos in 1614, the people of Kea in 1628, Thomas Klados in 1630 and the Prince of Wallachia, Alexandru Ghica from 1727 to 1740, the monastery's evolution was constantly hampered partly by quarrellings with nearby sketes and monasteries, most notably with Koutloumousiou monastery, over matters of land property and more importantly by two great fires in 1607 and in 1741 that burnt Stavronikita to the ground. However, the monastery continued to grow. In 1628 the catholicon was renovated and in 1770 the monastery's well-known aqueduct was built along with some of its chapels, such as the chapel of Saint Demetrius at the monastery's graveyard, the chapel of the Archangels and the chapel of the Five Martyrs.

During the Greek War of Independence in the early 19th century, Stavronikita, as well as the whole of Mount Athos, experienced harsh times. The monastery faced a harsh economic situation due to extraordinary debt that helped fund the war, while its monks were scattered after the Ottomans invaded Athos. Therefore, the monastery, along with some other athonite monasteries, was deserted and so were many of its holdings in Wallachia, Moldavia and elsewhere. This situation lasted for about a decade, after which the Ottomans left Athos and any monks that had survived started returning to the monastery.

However, the monastery's prosperity was again endangered by three great fires in 1864, 1874 and 1879 that caused great damage. The monastery was rebuilt but the monks became largely indebted again which led to further decline. This situation was partly reversed by the efforts of the abbot Theophilos, a monk formerly from Vatopedi.

In 1968, Vasileios (Gontikakis) became Abbot of Stavronikita and turned the monastery into a cenobitic one, thus reviving monastic life at Stavronikita. Vasileios moved to Iviron Monastery in 1990.[3]

Architecture

Stavronikita is the smallest of all athonite monasteries. Important sights of the monastery are its characteristics, the tower at the entrance, its aqueduct, as well as its centuries old cypress outside the western corner of the complex.

The catholicon of the monastery is dedicated to Saint Nicholas and is the smallest catholicon among its other athonite counterparts. It was built during the 16th century above a church that existed before and was dedicated to Theotokos. The catholicon is decorated with frescoes and an iconostasis by the famous icon-painter Theophanes of Crete and his son Symeon. The monastery's refectory is located on the upper floor at the southern side of the complex and bears some important iconographies.

During the second half of the 20th century the monastery had been largely abandoned and was slowly dilapidating. In addition, the rock on which the monastery was built had been severely damaged by a series of earthquakes. The rock was found to be slowly crumbling and sliding towards the sea which led to concerns about the future of the monastery's structural stability.

The Center for the Preservation of Athonite Heritage (Greek: Κέντρο Διαφύλαξης Αγιορείτικης Κληρονομιάς, abbreviated Κε.Δ.Α.Κ.), a state organization under the jurisdiction of the Ministry for Macedonia–Thrace, undertook the task of renovating and restoring the monastery. Extensive renovating work took place from 1981 to 1999 and by applying a complex engineering method the underlying rock was stabilized.[4]

Cultural treasures

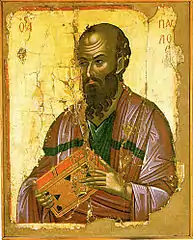

The monastery keeps a widely known 14th century icon of Saint Nicholas, known as "Streidas" (Greek: Άγιος Νικόλαος ο Στρειδάς, "Saint Nicholas of the Oyster") because when it was accidentally discovered at the bottom of the sea, an oyster had stuck at the forehead of St. Nicholas. According to the athonite tradition, when the monks of Stavronikita removed the oyster, the saint's forehead bled.

Stavronikita has a collection of notable icons and holy relics. The monastery also has in its possession priestly garments, ritual objects and other valuables. The monastery also has a collection of 171 manuscripts, out of which 58 are written on parchment. Some of the manuscripts bear notable iconography and decoration.

Notable people

References

- Kadas, Sotiris. The Holy Mountain (in Greek). Athens: Ekdotike Athenon. p. 113. ISBN 960-213-199-3.

- A. E. Bakalopulos (1973). History of Macedonia, 1354-1833. [By] A.E. Vacalopoulos. p. 166.

At the end of the 15th century, the Russian pilgrim Isaiah relates that the monks support themselves with various kinds of work including the cultivation of their vineyards....He also tells us that nearly half the monasteries are Slav or Albanian. As Serbian he instances Docheiariou, Grigoriou, Ayiou Pavlou, a monastery near Ayiou Pavlou and dedicated to St. John the Theologian (he no doubt means the monastery of Ayiou Dionysiou), and Chilandariou. Panteleïmon is Russian, Simonopetra is Bulgarian, and Karakallou and Philotheou are Albanian. Zographou, Kastamonitou (see fig. 58), Xeropotamou, Koutloumousiou, Xenophontos, Iveron and Protaton he mentions without any designation; while Lavra, Vatopedi (see fig. 59), Pantokratoros, and Stavronikita (which had been recently founded by the patriarch Jeremiah I) he names specifically as being Greek (see map 6).

- Dorobantu, Marius (2017-08-28). Hesychasm, the Jesus Prayer and the contemporary spiritual revival of Mount Athos (Master's thesis). Nijmegen: Radboud University. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- Center for the Preservation of Athonite Heritage Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine page about Stavronikita, with photos of the stabilization of the rock.