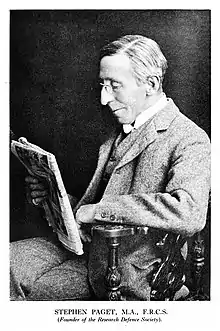

Stephen Paget

Stephen Paget (17 July 1855 – 8 May 1926) was an English surgeon and pro-vivisection campaigner.[1] On the basis of the works of Fuchs (see below), he proposed the "seed and soil" theory of metastasis, which claims the distribution of cancers are not coincidental. He was the son of the distinguished surgeon and pathologist Sir James Paget.[2]

Stephen Paget | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 17 July 1855 |

| Died | 8 May 1926 (aged 70) |

| Nationality | English |

| Known for | "Seed and soil" theory |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Oncology |

Biography

Paget was born on 17 July 1855 at Cavendish Square, London.[1] He was the fifth child and fourth son of Sir James Paget (1814–1899).[1]

Paget was educated at Shrewsbury School.[3] He matriculated at Christ Church, Oxford in 1874, graduating B.A. in 1878 (M.A. 1886).[4] He was a student at St Bartholomew's Hospital and obtained the F.R.C.S. in 1885.[5] He was elected assistant surgeon to the Metropolitan Hospital and was surgeon at West London Hospital. He was surgeon to the Throat and Ear Department at Middlesex Hospital.[5]

Paget died in Limpsfield on 8 May 1926.[5]

Proposed theory

Paget has long been credited with proposing the "seed and soil" theory of metastasis, even though in his paper "The Distribution Of Secondary Growths In Cancer Of The Breast" [6] he clearly states "…the chief advocate of this theory of the relation between the embolus and the tissues which receive it is Fuchs…".[7] Ernst Fuchs (1851-1930) an Austrian ophthalmologist, physician and researcher however, doesn't refer to the phenomenon as "seed and soil", but defines it as a "predisposition" of an organ to be the recipient of specific growths. In his paper, Paget presents and analyzes 735 fatal cases of breast cancer, complete with autopsy, as well as many other cancer cases from the literature and argues that the distribution of metastases cannot be due to chance, concluding that although "the best work in pathology of cancer is done by those who… are studying the nature of the seed…" [the cancer cell], the "observations of the properties of the soil" [the secondary organ] "may also be useful..."

Approbation of Louis Pasteur

In addition to other publications, he also wrote a book about Louis Pasteur titled Pasteur and After Pasteur. Pasteur's life is discussed from his early life through his accomplishments. Paget wrote this book in memoriam of Pasteur's life, and in the preface he states, "It has been arranged to publish this manual on September 28th, the day of Pasteur's death. That is a day which all physicians and surgeons -- and not they alone -- ought to mark on their calendars; and it falls this year with special significance to us, now that his country and ours are fighting side by side to bring back the world's peace."[8]

Vivisection

After his retirement from medical practice in 1910, Paget devoted much time to justifying vivisection.[9] He was secretary of the Research Defence Society.[9] He authored The Case Against Anti-Vivisection in 1904 and was the editor of For and Against Experiments on Animals, 1912. Paget was heavily criticized by anti-vivisectionists. In 1962, Archibald Hill noted that "Stephen Paget's death indeed was claimed by anti-vivisectionists as a direct consequence of their prayers."[10]

Criticism of Christian Science

In 1909, Paget authored a book, The Faith and Works of Christian Science which exposed the fallacies, inconsistencies, and dangers of Christian Science.[11]

Selected publications

- The Case Against Anti-Vivisection. 1904.

- Experiments on Animals. 1888. 3rd edition. 1907.

- John Hunter, Man of Science and Surgeon, 1728-1793. 1897.

- Ambroise Paré and His Times, 1510-1590 (1897)[12]

- Confessio Medici. 1908.[13]

- The Faith and Works of Christian Science. 1909.

- I Wonder: Essays for the Young People. 1911.

- For and Against Experiments on Animals. 1912.

- Pasteur and After Pasteur. 1914.

- Essays for Boys and Girls: A First Guide Toward the Study of the War. 1915.

- I Sometimes Think: Essays for the Young People. 1916.

- Sir Victor Horsley: A Study of His Life and Work. 1919.

- Henry Scott Holland: Memoir and Letters. 1921.

- I Have Reason to Believe. 1921.

References

- "Paget, Stephen (1855–1926)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- Henry Robert Addison; Charles Henry Oakes; William John Lawson; Douglas Brooke Wheelton Sladen (1907). "PAGET, Stephen". Who's Who. A. & C. Black. 59: 1351.

- Auden, J. E., ed. (1909). Shrewsbury School Register 1734–1908. p. 208. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- Foster, Joseph (1888–1892). . Alumni Oxonienses: the Members of the University of Oxford, 1715–1886. Oxford: Parker and Co – via Wikisource.

- "Mr. Stephen Paget" (PDF). Nature. 117 (2954): 831. 1926. Bibcode:1926Natur.117Q.831.. doi:10.1038/117831a0. S2CID 27126293.

- The Lancet, Volume 133, Issue 3421, 23 March 1889, Pages 571-573

- Ernst Fuchs, Das Sarkom des Uvealtractus, Wien, 1882. Graefe's Archiv für Ophthalmologie, XII, 2, p. 233.

- Stephen Paget (1914). "Pasteur and After Pasteur". A. & C. Black: 152.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Bates, A. W. H. (2017). Anti-Vivisection and the Profession of Medicine in Britain: A Social History. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 135. ISBN 978-1-137-55696-7

- Hill, Archibald. (1962). The Ethical Dilemma of Science and Other Writings. The Scientific Book Guild. p. 112

- R. T., H. (1909). "The Faith and Works of Christian Science". Nature. 81 (2087): 513–514. Bibcode:1909Natur..81..513R. doi:10.1038/081513b0. hdl:2027/uc2.ark:/13960/t6542nw14. S2CID 36613920.

- "Ambroise Paré and his times, 1510-1590". Nature. 58 (1490): 49–50. 1898. Bibcode:1898Natur..58...49.. doi:10.1038/058049a0. hdl:2027/nnc2.ark:/13960/t4zg7d06x. S2CID 3970134.

- "Confessio Medici" (PDF). Nature. 78 (1908): 54. 1908. Bibcode:1908Natur..78S..54.. doi:10.1038/078054c0. S2CID 28978298.

External links

Works by or about Stephen Paget at Wikisource

Works by or about Stephen Paget at Wikisource- Works by Stephen Paget at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Stephen Paget at Internet Archive