Stewarton

Stewarton (Scots: Stewartoun,[2] Scottish Gaelic: Baile nan Stiùbhartach)[3] is a town in East Ayrshire, Scotland. In comparison to the neighbouring towns of Kilmaurs, Fenwick, Dunlop and Lugton, it is a relatively large town, with a population estimated at over 7,400.[4] It is 300 feet (90 metres) above sea level.[5] The town is served by Stewarton railway station.

| Stewarton Stewartoun (Scots)

| |

|---|---|

| Town | |

The Cross in Stewarton, East Ayrshire, with a view towards Fenwick. | |

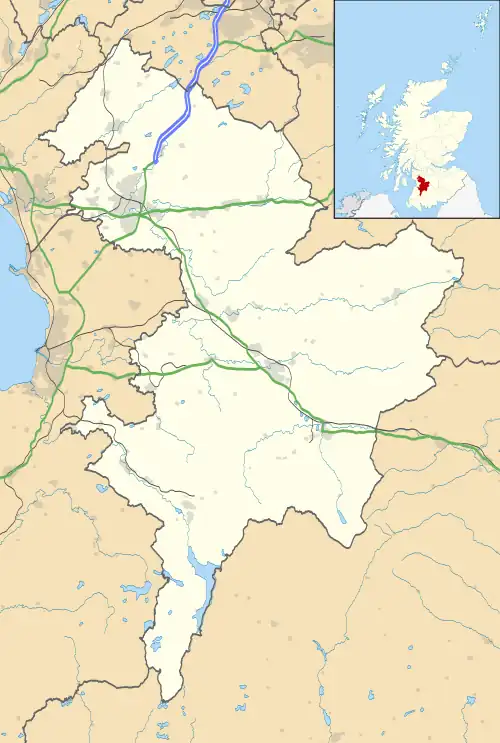

Stewarton Stewartoun (Scots) Location within East Ayrshire | |

| Population | 7,770 (mid-2020 est.)[1] |

| Language | English Scots |

| Council area | |

| Lieutenancy area | |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Kilmarnock |

| Postcode district | KA3 |

| Police | Scotland |

| Fire | Scottish |

| Ambulance | Scottish |

| UK Parliament | |

| Scottish Parliament | |

| Website | Stewarton Website |

Stewarton lies within Strathannick, with the Annick Water flowing through the town. The community is in a rural part of East Ayrshire, about 6 miles (10 kilometres) north of Kilmarnock and to the East of Irvine. In the past, Stewarton served as a crossroads between the traditional routes from Kilmarnock, Irvine and Ayr to the city of Glasgow. However, in recent times, the M77 motorway has bypassed the town. The old road is known as the "Auld Glesga Road" (Or the "Old Glasgow Road") and the former name is still used by locals.

History

King Malcolm Canmore and Friskin

Historical records show that Stewarton has existed since at least the 12th century with various non-historical references to the town dating to the early 11th century. The most famous of these non-historical references concerns the legend of Máel Coluim III the son of Donnchad I of Scotland who appears as a character in William Shakespeare's play Macbeth. As the legend goes, Mac Bethad had slain Donnchad to enable himself to become king of Scotland and immediately turned his attention towards Donnchad's son Máel Coluim (the next in line to the throne). When Máel Coluim learned of his father's death and Mac Bethad's intentions to murder him, he fled for the relative safety of England. Unfortunately for Máel Coluim, Mac Bethad and his associates had tracked him down and were gaining on him as he entered the estate of Corsehill on the edge of Stewarton. In panic Máel Coluim pleaded for the assistance of a nearby farmer named either Friskine or Máel Coluim (accounts differ) who was forking hay on the estate. Friskine/Máel Coluim covered Máel Coluim in hay, allowing him to escape Mac Bethad and his associates. He later found refuge with King Harthacanute, who reigned as Canute II, King of England and Norway and in 1057, after returning to Scotland and defeating Mac Bethad in the Battle of Lumphanan in 1057 to become King of Scots, he rewarded Friskine's family with the Baillie of Cunninghame to show his gratitude to the farmer who had saved his life 17 years earlier. The Cunninghame family logo now features a "Y" shaped fork with the words "over fork over" underneath - a logo which appears in various places in Stewarton, notably as the logo of the two primary schools in the area - Lainshaw primary school and Nether Robertland primary school.

Another reference to Stewarton, this time a historical recorded version, is that one Wernebald was given the Cunninghame lands by his superior, Hugh de Morville, the builder of Kilwinning Abbey who lived at this time in Tour near Kirkland in Kilmaurs. The family were originally from Morville in Normandy (Wernebald was from Flanders) and had been established in Scotland for at least twenty years when one of the family was involved in the murder of Thomas Becket. Dervorguilla of Galloway, mother of John Balliol, was a daughter of the Morvilles on her mother's side, and when Robert the Bruce won the crown the family of Balliol lost their lands in Cunninghame. The Red Comyn, whom Bruce murdered, was a nephew of Balliol. William Cunninghame de Lamberton was Archbishop of St. Andrews and a supporter of Bruce.

Pont[7] in 1604 - 08 records that so thickly was the district about Stewarton and along the banks of the Irvine populated for a space of 3 or 4 miles (5 or 6 kilometres) "that well traveled men in divers parts of Europe (affirm) that they have seen walled cities not so well or near planted with houses so near each other as they are here, wherethrough it is so populous that, at the ringing of a bell in the night for a few hours, there have seen convene 3000 able men, well-horsed and armed."[8]

The Murder of the 4th Earl of Eglinton

Another significant event from Stewarton's history involves the Cunninghame family. In the 16th century Ayrshire was divided into three regions or bailiaries - Kyle, Carrick and Cunninghame. The two powerful families residing in Cunninghame - the Cunninghame's and the Montgomeries - had been involved in a dispute over landholdings which came to a head in 1586 when Hugh, the 4th Earl of Eglinton was attacked at the ford on the Annick Water (which flows through Stewarton) by 30 or so members of the Cunninghame clan and shot dead by John Cunninghame of Clonbeith. Hugh is said to have been on his way to attend the court of King James VI at Stirling when he decided to stop off at Langshaw House (now Lainshaw house which was for a long time a home for the elderly) to dine with his associates. The lady of the house Lady Montgomery - told several of her Cunninghame associates who lived in the area of the Earl's planned visit. As a response to the killing the Montgomery family declared they would kill every Cunninghame who had been at the river that day and a series of 'tit for tat' killings were carried out between the two families. John Cunninghame of Clonbeith was eventually slain in Hamilton, Scotland, but several of those responsible for the murder fled to Denmark and were eventually granted a pardon by King James upon his marriage to Anne of Denmark.

Lady Montgomery, who was alleged to have signaled the murderers by placing a white 'napkin' on a window sill, is said to have escaped and lived with her retainer Robert Kerr at Pearce Bank (now High Peacockbank) for several years until the 'hue and cry' died down at which point she returned to the castle and was not molested on the understanding that she did not 'show her face' outside of the grounds. A path known as the 'Weeping or Mourning Path' runs upstream from the Annick (previously Annack or Annock Water) Ford and this is where the Earl's widow is said to have wept as she later followed the trail of blood left behind as his panicked horse took him away from Bridgend. The Earl's body was placed in Lainshaw Castle until arrangements were made to remove it to Eglintoun Castle.

Corsehill and Ravenscraig Castles

The name Ravenscraig or Reuincraig is derived from 'Ruin Crag', i.e. ruined castle. Godfrey de Ross and his family of Corsehill Castle were Lords of Liddesdale in the Borders and later on the Cunninghames became the holders. Corsehill (also Crosshill) castle is said to have been on the east side of the Corsehill Burn. The 1860 OS map does record the site of Templehouse which had a small fortalice associated with it and its site was at Darlington, the village which lay just beyond Stewarton on the Kingsford road before the East Burn. Corsehill castle is shown in one old print of 1691 by Gross as Corsehill House and substantial remains existed until the railway was constructed and most of the ruins were used to build the embankment. It is recorded that an avenue of trees ran down from the well planted Corsehill into Stewarton. The single tower that remains today (2006) of Ravenscraig / Corsehill was repaired to stabilise it. It seems that Ravenscraig and Corsehill Castles were separate entities, and that a vague memory of Templehouse and its fortalice at Darlington on the lands of Corsehill farm, may have caused some extra confusion as in the King’s Kitchen tale of the location of the Baronial residence. An area opposite the site of Templehouses was known as 'The Castle' and this may reflect the existence of the castle or fortalice here (Hewitt 2006).

Archibald Adamson in his 'Rambles Round Kilmarnock' of 1875 only records three castles, these being Robertland, Auchenharvie and Corsehill. He makes no mention of the name Ravenscraig, calling the site he visited Corsehill. Aitken only marks Crosshill Castle in 1829 on the west side of the Corsehill Burn. The first OS maps show only the existing castle site, so the new survey has not perpetuate the error. To sum up, the map in Pont's 'Cuninghame' of 1604-8 shows two buildings, "Reuincraige" and "Corshill", at approximately NS 417 467 and NS 422 465 respectively, and Dobie (1876) comments that the two have often been confused, but that "Reuincraig" stood on the W of the Corsehill Burn and "Corsehill Mansion" on its E. "Reuincraig", he says, was so modernised about 1840 that it was difficult to realise that it had been ruined in 1608, while the ruins of "Corsehill" were removed about the beginning of the 19th century and only foundations could be traced when he wrote. He also thought that "Reuincraig" (i.e. Ruin Craig) was not an original name. If Dobie is correct, the ruins published as "Corsehill Castle" on the OS 6", must be those of "Reuincraig", both because they are standing remains, and because they are on the W bank of the burn. Macgibbon and Ross, describing "Corsehill Castle" at the end of the 19th century as a very ruinous mansion, evidently of late date and apparently of the L-plan, and ascribe it to the period 1542-1700, must be referring to "Reuincraig". Grose, in 1791, published an illustration of "Corshill House", but does not give it a close siting. As, however, he mentions that "at a small distance from this ruin are some small remains of a more ancient building belonging to the same family", he is also probably referring to "Reuincraig", the "small remains" being those of "Corsehill". (Grose 1791); (MacGibbon) and (Ross 1889).

General Roy's Military Survey of Scotland (1745–55) marks 'Ravenscraig' as 'Old Corsehill' and also marks the 'new' Corsehill on the other side of the burn, thereby apparently confirming that they both had the same name and one replaced the other, although only 'Old Corsehill' is still in any way visible, just the foundations of 'new' Coresehill being apparent in 2007. The same map shows buildings named 'Temple' in the area of 'Templehouse'.

The Conventicles and the Highland host

To prevent the Covenanters holding 'Conventicles', King Charles II moved highland troops, the 'Highland Host' into the west-land of Ayrshire.[9] "They took free quarters; they robbed people on the high road; they knocked down and wounded those who complained; they stole, and wantonly destroyed, cattle; they subjected people to the torture of fire to discover to them where their money was hidden; they threatened to burn down houses if their demands were not at once complied with; besides free quarters they demanded money every day; they compelled even poor families to buy brandy and tobacco for them; they cut and wounded people from sheer devilment." The cost of all this amounted to £6062 12s 8d in Stewarton parish.[10]

Micro history of the area

Cairnduff Hill overlooks Stewarton and is the site of the remnants of a Bronze Age burial cairn inside of which three urns or beakers were found in the 19th century containing bones and relicts. In 1847 the old Barony Court House still stood near the Avenue running up towards Corsehill.[11] The War Memorial used to stand outside the front of the library in the avenue square and was moved to provide a more suitable setting near Standalane house above Lainshaw primary school.

People and businesses from Stewarton

Dunlop cheese was made in Stewarton as well as many other Ayrshire localities, such as Beith.[12]

Robert Burns's uncle, Robert Burnes, is known to have helped guard the Stewarton Laigh Church graveyard against the activities of body snatchers.[13] David Dale, industrialist, merchant, philanthropist and founder of the world famous cotton mills in New Lanark, was born in Stewarton in 1739. He was the son of William Dale, a general dealer in the village.[14]

William Jack was born here in 1834.[15]

International women's footballer Rose Reilly grew up in Stewarton, before being forced to leave to pursue a career in professional football. [16] but returned in later years and now resides in the area. The sports centre located in the town has since been renamed in honour of her.[17]

Sports

The ground of Stewarton's cricket club was located between Lochridge and Ward Park house. Stewarton Golf Club (now defunct) was founded in 1912. The club disappeared following WW2.[18]

Accidents and incidents

On 27 January 2009, a BP tanker train carrying liquid fuels (diesel and heating oil) from Mossend to Riccarton was derailed at the bridge over the Stewarton to Kilmaurs road at Peacockbank Farm. Several wagons subsequently caught fire.[19] The Lochrig Burn was badly polluted, however the Annick Water escaped major contamination.

Geography and Climate

The Stewarton Flower, so named due to its local abundance and recorded as such by the Kilmarnock Glenfield Ramblers,[20] is otherwise known as Pink Purslane (Claytonia sibirica) is found in damp areas. This plant was introduced from North America in Victorian times, quite possibly at the Robertland Estate. In 1915 it was stated to have been in the area for over 60 years and was abundant on the Corsehill Burn below Robertland in 1915. As far away as Dalgarven Mill the white flowered variety still dominates. The plant is very adept at reproducing by asexual plantlets and this maintains the white gene pool around Stewarton. The pink variety has not been able to predominate here, unlike almost everywhere else in the lowlands of Scotland, England and Wales. Claytonia sibirica is a seriously destructive alien invader which should not be transplanted to other sites.

Transport

Stewarton railway station was opened in 1871 by the Glasgow, Barrhead and Kilmarnock Joint Railway. The station closed in 1966, reopening in 1967. In 2009-2010 the line was partly re-doubled and the train frequency increased to two trains an hour in each direction. The station was rebuilt and a second platform brought into use.

Thomas Oliver was titled "roadmaker in Stewarton", being employed by the Kilmarnock to Irvine road committee. He worked with the specifications of a road 24 feet (7.3 metres) wide, 14 inches (36 centimetres) thick in the middle to 10 in (25 cm) in the sides, the understratum to be made of stones not exceeding 6 lb (2.5 kg) tron weight and 6 in (15 cm) thick, etc. Very precise requirements which would cost seven shilling per fall from Annick Bridge to Gareer Burn, but ten shillings per fall from Gareer Burn to Corsehouse bridge (Crosshouse) because of the lack of suitable materials locally.[21]

Local events

Stewarton, like many other Scottish towns, holds an annual gala festival at the beginning of summer. Dating back to the days when Stewarton had a prosperous trade in bonnet-making, the 'Bonnet Guild' organises activities for the local residents and proclaims a 'Corsehill Queen', the most academically successful girl in 2nd year at Stewarton Academy.[22]

The Cadgers’ Fair was an annual event unique to Stewarton in the 18th Century. "Our annual fair took place on Monday last. In the morning there was a large turnout of cattle. . . . Our Cadgers’ procession was a slight improvement on some former occasions, and headed by a brass band they marched through the town, thence to a field on the farm of Robertland where the races took place". Horses were traded and much of the 'action' took place in the Avenue Square.[23]

See also

References

- Notes

- "Mid-2020 Population Estimates for Settlements and Localities in Scotland". National Records of Scotland. 31 March 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- List of railway station names in English, Scots and Gaelic – NewsNetScotland Archived January 22, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba ~ Gaelic Place-Names of Scotland

- "Stewarton (East Ayrshire, Scotland, United Kingdom) - Population Statistics, Charts, Map, Location, Weather and Web Information". www.citypopulation.de. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- Groome, Francis H. (1903). Ordnance Gazetteer of Scotland. Pub. Caxton. London. P. 1506.

- Ainslie, John (1779), Lainshaw Estate Map.

- Pont, Timothy (1604). Cuninghamia. Pub. Blaeu in 1654.

- Robertson, William (1908). Ayrshire. Its History and Historic Families. Vol.1. Pub. Dunlop & Dreenan. Kilmarnock. P. 303

- Robertson, William (1905). Old Ayrshire Days. Pub. Stephen & Pollock. Ayr. P. 299 - 300.

- Robertson, William (1905). Old Ayrshire Days. Pub. Stephen & Pollock. Ayr. P. 203.

- Search over Lainshaw, Page 33

- Smith, John. Cheesemaking in Scotland - A History. Scottish Dairy Association. ISBN 0-9525323-0-1. P. 24.

- Milligan, Susan. Old Stewarton, Dunlop and Lugton. Pub. Ochiltree. ISBN 1-84033-143-7.

- For a full biography of Dale: see McLaren, D. J. (2015). David Dale: A Life. Stenlake Publishing Ltd.

- Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X.

- "Interview: Rose Reilly on why she was never going to turn down MBE". www.scotsman.com. 2 January 2020. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- "Football Superstar to Officially Re-open Sports Centre - East Ayrshire Council News". www.east-ayrshire.gov.uk. 4 March 2020. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- “Stewarton Golf Club”, Golf's Missing Links.

- METRO. January 28, 2009. p. 5.

- Dickie, T. W. (1915), Robertland, 10/07/1915. Annals of the Kilmarnock Glenfield Ramblers Society. 1913 - 1919. P. 110.

- McClure, David (1994). Tolls and Tacksmen. Ayr Arch & Nat Hist Soc. Ayrshire Monograph No.13. P. 10.

- Bonnet Festivals – Stewarton.com website

- Cuthbertson, Page 169

- Sources

- Adamson, Archibald R. (1875). Rambles Round Kilmarnock. Pub. Kilmarnock. p. 156.

- Best, Nicholas (1999). The Kings and Queens of Scotland. Pub. London. ISBN 0-297-82489-9.

- Buchan, Peter (1840). The Eglinton Tournament and Gentlemen Unmasked. London : Simpkin, Marshall & Co.

- Cuthbertson, David Cuningham (1945). Autumn in Kyle and the Charm of Cunninghame. London : Jenkins.

- Dobie, James (1876). Pont's Cunnighame. Pub. Glasgow.

- Hewitt, Davie (2006). Personal communication.

- MacGibbon, T. and Ross, D. (1887–92). The castellated and domestic architecture of Scotland from the twelfth to the eighteenth centuries, 5v, Edinburgh, Vol.3, 495.

- Search over Lainshaw, Register of Sasines

External links

- Video of the Lainshaw Woods WW2 bomb crater

- Video history of the Corsehill Castles, the Cunninghams and Stewarton

- Cairnduff Hill, High Peacockbank

- RCAHMS Canmore archaeology site

- http://www.lawrie.freewire.co.uk/MAPS/stewartonmap.gif

- https://web.archive.org/web/20071009120916/http://www.stewarton.org/History/SLAUGHTER_AT_STEWARTON.htm

- https://web.archive.org/web/20071009120944/http://www.stewarton.org/History/The%20Bonnet%20Toun%20-%20Alastair%20Barclay/Cover.htm

- Maps at the National Library of Scotland

- 1860 OS Maps

- General Roy's Military Survey map of Scotland.

- A Researcher's Guide to Local History terminology

- http://www.stewarton.com

- The Law or Pinkie Hill

- Video footage and narration on Corsehill Mills