Stratioti

The Stratioti or Stradioti (Greek: στρατιώτες stratiotes; Albanian: Stratiotë, Stratiotët;,[2] Italian: stradioti, stradiotti, stratioti, strathiotto, strathioti; French: estradiots; Serbo-Croatian: stratioti, stradioti; Spanish: estradiotes[3]) were mercenary units from the Balkans recruited mainly by states of southern and central Europe from the 15th century until the middle of the 18th century.[4] They pioneered light cavalry tactics in European armies in the early modern era.[5]

| Stratioti | |

|---|---|

| |

| Active | 15th to 18th centuries |

| Type | Mercenary unit |

| Role | Light cavalry |

Name

One hypothesis proposes that the term is the Italian rendering of Greek στρατιώτες, stratiotes or στρατιώται, stratiotai (soldiers), which denoted cavalrymen who owned pronoia fiefs in the late Byzantine period.[6][7] It was also used in Ancient Greek as a general term for a soldier being part of an army.[8] According to another hypothesis, it derives from the Italian word strada ("street") which produced stradioti "wanderers" or "wayfarers", figuratively interpreted as errant cavalrymen.[6] Italian variants are stradioti, stradiotti, stratioti, strathiotto, strathioti. In Albanian they are called stratiotë (definite: stratiotët)[2] in French estradiots, in Serbo-Croatian: stratioti, stradioti, in Spanish estradiotes.[3]

Since many stradioti wore a particular cap, in Venice the name cappelletti (sing. cappelletto) was initially used as a synonym for stradiotti or albanesi.[9][10][11][12] In the 16th and 17th centuries the term cappelletti was mainly used for light cavalry recruited from Dalmatia.[13] A feature that distinguished the cappelletti form the stradiotti was their increasing usage of firearms.[14] From the 17th century Venice recruited light cavalry no longer from the Morea, but mainly from Dalmatia and Albania,[13] and the cappelletti gradually replaced the stradiotti.[15] However they had not the same success as light cavalry was gradually abandoned.[16]

History

The stradioti were recruited in Albania, Greece, Dalmatia, Serbia and Cyprus.[17][18][19][20] Those units continued the military traditions of Byzantine and Balkan cavalry warfare.[21] As such, they had previously served Byzantine and Albanian rulers, they then entered Venetian military service during the Ottoman-Venetian wars in the 15th century.[5] It has been suggested that a ready pool of Albanian stradioti was the product of the northern Albanian tribal system of feud (Gjakmarrja) and consequent emigration.[22] The precise year when stratioti units began to be recruited in western armies is not known. However, under 1371 state decrees of the Venetian Republic those Greeks that lived in Venetian controlled territories were allowed to join the Venetian army.[23]

The precise definition of their ethnic identity was the subject of careful study, while modern scholarship concludes that they were Albanians and Greeks who mainly originated from the Peloponnese.[24] Studies on the origin of their names indicate that around 80% of the stradioti were of Albanian origin, and very few of Slav origin (Crovati). The remainder were Greek, most of whom were captains.[25] Some of the officers' surnames who were of Greek origin are Palaiologos, Spandounios, Laskaris, Rhalles, Komnenos, Psendakis, Maniatis, Spyliotis, Alexopoulos, Psaris, Zacharopoulos, Klirakopoulos, and Kondomitis.[5] A number of them, such as the Palaiologoi and Komnenoi, were members of Byzantine noble families.[5][26] Others seemed to be of South Slavic origin, such as Soimiris, Vlastimiris, and Voicha.[5] Some renowned Albanian stratioti were the Alambresi, Basta, Bua, Meksi, Capuzzimadi, Crescia, and Renesi.[27] The study on the names of the stradioti does not indicate that most of them came directly from Albania proper, rather from the Venetian holdings in southern and central Greece. The stradioti who moved with their families to Italy in the late 15th and early 16th centuries had been born in the Peloponnese, where their ancestors immigrated in the late 14th and early 15th century, after the request of the Byzantine Despots of the Morea, Theodore I and Theodore II Palaiologos, who invited the Albanians to serve as military colonists in the Peloponnese in the attempt to resist Ottoman expansion in the Balkans.[5]

While the bulk of stratioti were of Albanian origin from Greece, by the middle of the 16th century there is evidence that many of them had been Hellenized and in some occasions even Italianized. Hellenization was possibly underway prior to service abroad, since stradioti of Albanian origin had settled in Greek lands for two generations before their emigration to Italy. Moreover, since many served under Greek commanders and together with the Greek stradioti, this process continued. Another factor in this assimilative process was the stradioti's and their families' active involvement and affiliation with the Greek Orthodox or Uniate Church communities in the places they lived in Italy.[5] On the other hand the military service in Italy and other European countries slowed and in some cases reversed the process of Hellenization. Those Albanians of Greece who migrated to Italy have been able to maintain their identity more easily than the Arvanites who remained in Greece, hence constituting a part of the Arbëreshë people of Italy.[28]

Activity

Republic of Venice

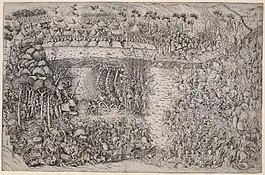

With the end of the Byzantine Empire in 1453 and the breakup of the Despotate of the Morea through civil war between 1450 and 1460, Albanian and Greek stradioti increasingly found refuge and employment with the Venetians.[5] The Republic of Venice first used stratioti in their campaigns against the Ottoman Empire and, from c. 1475, as frontier troops in Friuli. Starting from that period, they began to almost entirely replace the Venetian light cavalry in the army. Apart from the Albanian stradioti, Greek and Italian ones were also deployed in the League of Venice at the Battle of Fornovo (1495).[29] The mercenaries were recruited from the Balkans, mainly Christians but also some Muslims.[30] In 1511, a group of stratioti petitioned for the construction of the Greek community of Venice's Eastern Orthodox church in Venice, the San Giorgio dei Greci,[31] and the Scuola dei Greci (Confraternity of the Greeks), in a neighborhood where a Greek community still resides.[32] Impressed by the unorthodox tactics of the stratioti, other European powers quickly began to hire mercenaries from the same region.

Since the first Ottoman–Venetian war (1463–1479) and later Ottoman–Venetian wars of the 15th and 16th century Stratioti units, both Albanian and Greeks served the Venetian forces in the Morea. In addition the Venetian authorities allowed the settlement of Albanians in Napoli di Romagna (Nauplion) in the Argolis region, outside of the walls of the city.[5][33] Relations between the two groups and relations between Albanians, Greeks and the central Venetian administration varied. Some families intermarried with each other, while other times disputes erupted as in 1525 when both Greeks and Albanians asked to serve only under the leadership of their own commanders.[34] In the reports of the Venetian commander of Nauplion, Bartolomeo Minio (1479–1483) stressed that the Albanian stratioti were unreliable contrary to the Greek units which he considered loyal. In other reports, attitudes towards Albanians are positive. As Venice lost territory to the Ottomans in the Morea, the numbers of Stratioti the administration employed lowered. By 1524, no more than 400-500 Stratioti remained in Venetian Argolis.[34]

By 1589, four Venetian Stratioti companies remained in Crete. Reports to the Provveditore generale di Candia warn him that the Stratioti should be "actual Albanians" (veramene Albanesi) unlike the Stratioti in Crete who were not "real Albanians but Cypriots and locals who have no military experience". While the origins of these Stratioti were indeed Albanian, more than a century since the settlement of their ancestors in Crete had passed and they had become integrated in the local society. Venetian sources described them more as "farmers than stradioti" who spoke Greek (parlavano greco).[35]

The presence of the Albanian stradioti in Venetian territories for many decades had a significant impact in the way Venetians perceived what it meant to be Albanian.[36] Although Stratioti units settled in western Europe and finally lost contact with their homelands, they were crucial in the spread of Greek-Orthodox and Uniate communities in Venice, as well as in other Italian and Dalmatian cities.[37]

France

France under Louis XII recruited some 2,000 stradioti in 1497, two years after the battle of Fornovo. Among the French they were known as estradiots and argoulets. The term "argoulet" is believed to come either from the Greek city of Argos, where many of argoulets come from (Pappas), or from the arcus (bow) and the arquebuse.[38] For some authors argoulets and estradiots are synonymous but for others there are certain differences between them. G. Daniel, citing M. de Montgommeri, says that argoulets and estradiots have the same armoury except that the former wear a helmet.[39] According to others "estradiots" were Albanian horsemen and "argoulets" were Greeks, while Croatians were called "Cravates".[40]

The argoulets were armed with a sword, a mace (metal club) and a short arquebuse. They continued to exist under Charles IX and are noted at the battle of Dreux (1562). They were disbanded around 1600.[41] The English chronicle writer Edward Hall described the "Stradiotes" at the battle of the Spurs in 1513. They were equipped with short stirrups, small spears, beaver hats, and Turkish swords.[42]

The term "carabins" was also used in France as well as in Spain denoting cavalry and infantry units similar to estradiots and argoulets (Daniel G.)(Bonaparte N.[43]). Units of Carabins seem to exist at least till the early 18th century.[44]

Corps of light infantry mercenaries were periodically recruited from the Balkans or Italy mainly during the 15th to 17th centuries. In 1587, the Duchy of Lorraine recruited 500 Albanian cavalrymen, while from 1588 to 1591 five Albanian light cavalry captains were also recruited.[45]

Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples hired Albanians, Greeks and Serbs into the Royal Macedonian Regiment (Italian: Reggimento Real Macedone), a light infantry unit active in the 18th century.[46] Spain also recruited this unit.[47]

Spain

Stratioti were first employed by Spain in their Italian expedition (see Italian Wars). Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba ("Gran Capitan") was sent by King Ferdinand II of Aragon ("the Catholic") to support the kingdom of Naples against the French invasion. In Calabria Gonzalo had two hundred "estradiotes Griegos, elite cavalry".[48]

Units of estradiotes served also in the Guard of King Ferdinand and, along with the "Alabarderos", are considered the beginnings of the Spanish Royal Guard.[49]

England

- In 1514, Henry VIII of England, employed units of Albanian and Greek stradioti during the battles with the Kingdom of Scotland.[32][50]

- In the 1540s, Duke Edward Seymour of Somerset used Albanian stradioti in his campaign against Scotland.[51]

- An account of the presence of stratioti in Britain is given by Nikandros Noukios of Corfu. In about 1545 Noukios followed as a non-combatant the English invasion of Scotland where the English forces included Greeks from Argos under the leadership of Thomas of Argos whose "Courage, and prudence, and experience of wars" was lauded by the Corfiot traveller.[52][note 1] Thomas was sent by Henry VIII to Boulogne in 1546, as commander of a battalion of 550 Greeks and was injured in the battle.[53] The King expressed his appreciation to Thomas for his leadership in Boulogne and rewarded him with a good sum of money.

Holy Roman Empire

In the middle of the 18th century, Albanian stratioti were employed by Empress Maria Theresa during the War of the Austrian Succession against Prussian and French troops.[54]

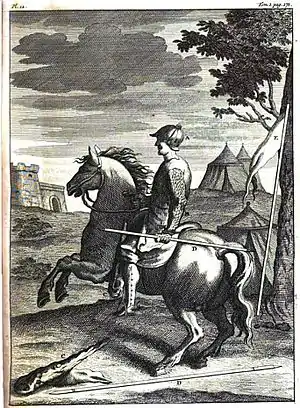

Tactics

The stratioti were pioneers of light cavalry tactics during this era. In the early 16th century light cavalry in the European armies was principally remodeled after Albanian stradioti of the Venetian army, Hungarian hussars and German mercenary cavalry units (Schwarzreiter).[55] They employed hit-and-run tactics, ambushes, feigned retreats and other complex maneuvers. In some ways, these tactics echoed those of the Ottoman sipahis and akinci. They had some notable successes also against French heavy cavalry during the Italian Wars.[56] Their features resembled more the akinjis than the sipahis, this occurred most probably as a result of the defensive character of 15th century Byzantine warfare.[57]

Practices

They were known for cutting off the heads of dead or captured enemies, and according to Commines they were paid by their leaders one ducat per head.[58]

Equipment

The stradioti used javelins, swords, maces, crossbows, bows, and daggers. They traditionally dressed in a mixture of Ottoman, Byzantine and European garb: the armor was initially a simple mail hauberk, replaced by heavier armor in later eras. As mercenaries, the stradioti received wages only as long as their military services were needed.[59] They wore helmets which were known as "chaska", from the Spanicsh word "casco".[60] From the end of the 15th century they also used gunpowder weapons.[61]

The stradioti wore particular caps, which were very similar to those of the Albanian ethnographic region of Labëria, with conical shape and a small extension,[62] reinforced inside by several sheets of paper attached together, ensuring surprising resistance.[63] Those caps were called chapeau albanois (Albanian hat) in French.[12]

Notable stratioti

- Thomas of Argos, Greek captain of a battalion of 550 Greek stratioti who served in the English army in the era of Henry VIII. Thomas was injured in the Siege of Boulogne (1546) fighting victoriously against a unit of more than 1,000 French (Moustoxydes, 1856)

- Giorgio Basta, Italian general, diplomat, and writer of Arbëreshë origin

- Peter Bua, Albanian stratioti captain in the Morea[64]

- Mercurio Bua (son of Peter Bua), stratioti captain who participated in the important phases of the Italian Wars between 1489 and 1559 serving the Republic of Venice, the Duke of Milan Ludovico Sforza, the Kingdom of France, the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I and then Venice again[65][66][67][68]

- Theodore Bua, Albanian stratioti captain

- Demetrio Capuzzimati, Albanian stratioti captain in Flanders and Italy

- Teodoro Crescia, Albanian stratioti captain in Italy, Flanders, Germany

- Panagiotis Doxaras, Greek horseman by the Venetian army and painter (1662–1729)

- Mark Gjini Albanian stratioti captain serving under Venice

- Krokodeilos Kladas, Stratioti captain and military leader

- Petros Lantzas (d. 1608), Greek stratioti captain

- Michael Tarchaniota Marullus, Greek Renaissance scholar, poet and humanist

- Emmanuel Mormoris, 16th century commander

- Graitzas Palaiologos, Greek stratioti commander[69]

- Giovanni Renesi I (active 1568–1590), Albanian stratioti, served in the Kingdom of Naples

- Giovanni Renesi II (1567–1624), Albanian stratioti in Dalmatia and Republic of Venice; active in anti-Ottoman espionage and military action

- Demetrio Reres, Albanian Stratioti captain and nobleman

Notes

- Cramer's translation of A.Noukios' work stops exactly where the text starts referring to Thomas of Argos. A Greek historian, Andreas Moustoxydes, published the missing part of the original Greek text, based on a manuscript kept in the Ambrosian Library (Milan). After Cramer's asterisks (end of his translation) the text continues as follows:

[Hence, indeed, Thomas also, the general of the Argives from Peloponnesus, with those about him ***] spoke to them so:

“Comrades, as you see we are in the extreme parts of the world, under the service of a King and a nation in the farthest north. And nothing we brought here from our country other than our courage and bravery. Thus, bravely we stand against our enemies, …. Because we are children of the Greeks and we are not afraid of the barbarian flock. …. Therefore, courageous and in order let us march to the enemy, … , and the famous since olden times virtue of the Greeks let us prove with our action.“

(*) Έλληνες in the original Greek text. This incident happened during the Sieges of Boulogne (1544–1546).

References

- Nicolle & McBride 1988, p. 44.

- Selim Islami; Kristo Frashëri; Aleks Buda (1969). Historia e popullit shqiptar: Përgatitur nga një kolektiv punonjësish shkencorë të sektorëve të historisë së kohës së lashtë dhe të kohës së mesme. Enti i teksteve dhe i mjeteve mësimore i Krahinës Socialiste Autonome të Kosovës. p. 150.

Stratiotët nuk mundën t'i shpëtonin varfërimit dhe me kohë filluan t'i shisnin tokat. Gjatë shek .X, perandorët bizantinë u përpoqën ta ndalonin shitjen e tokave stratiote që sillte dobësimin e fuqisë së tyre ushtarake.

- Floristán 2020, p. 232.

- Tardivel 1991, p. 134.

- Pappas, Stradioti.

- Pappas, Stradioti : "Two versions of the name stradioti have been cited by sources, while scholars have debated which of these versions is accurate. According to some authorities, the terms stradiotto and stradioti (plural) are Italian variants of the Greek stratiotês or stratiotai which generally means soldier, but in later Byzantine times meant cavalry man who held a military fief (pronoia). Other authors assert that stradioti came from the Italian root strada (road) and that the term stradiotto meant a wanderer or wayfarer, thus denoting an errant cavalrymen or warrior (..) The bulk of primary sources in Italian, such as Coriolano Cippico, Marino Sanuto and Venetian state documents, use stradiotto/stradioti, adopted by this paper, or strathiotto/strathioti.[18] French sources, such as Philip de Comines, use the variation estradiot/estradiots.[19] Although arguments on the side of the wayfarer theory predominate, the fact that some of the older Latin sources from the early 15th century use a variation of the Greek stratiotes tends to make this writer favor the "soldier" theory".

- Trecanni (ed.), Grande Enciclopedia Italiana, "Stradioti": "dal basso greco στρατιώται"; Societa Italiana di Studi Araldici 2005, p. 3: "dal greco stratiòta".

- Melville-Jones, John R. (2002). Venice and Thessalonica, 1423–1430: The Venetian documents. Unipress. p. xxiv. ISBN 978-88-8098-176-3.

Greek stratiotes , a general term for a soldier forming part of an army , at this period in the Venetian documents the word seems

- "cappellétto" in treccani.it.

- Gramaticopolo 2016, p. 42.

- Folengo & Mullaney 2008, p. 491.

- Minchella 2015, p. 97.

- Gramaticopolo 2016, pp. 8, 9, 56.

- Gramaticopolo 2016, pp. 56–57.

- Birtachas 2018, p. 326: "the paper examines its recruitment firstly of the so-called stradiots (stradioti), mercenary light cavalry corps of Greek, Albanian, and Slav origin, as well as of the likewise mounted cappelletti, which are the development of the stradiots from the seventeenth century; and secondarily of the mercenary groups of ‘Greek’ infantry named compagnie or milizie greche."

- Gramaticopolo 2016, p. 9.

- Nicolle, 1989.

- B. N. Floria, "Vykhodtsy iz Balkanakh stran na russkoi sluzhbe," Balkanskia issledovaniia. 3. Osloboditel'nye dvizheniia na Balkanakh (Moscow, 1978), pp. 57-63.

- Hungary and the fall of Eastern Europe 1000–1568 by David Nicolle, Angus McBride: "John Comnenus [...] settled Serbs as stratioti around Izmir..."

- Nicol, Donald M. (1988). Byzantium and Venice: A Study in Diplomatic and Cultural relations. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 37. "Young men recruited from among Greeks and Albanians. They were known as stradioti from the Greek word for soldier."

- Pappas, 1991, p. 7: "The stratioti continued the Byzantine and Balkan traditions of cavalry warfare, which emphasized ambushes, hit-and-run assaults, feigned retreats, counterattacks and other tactics little known to western armies of the time. Indeed, when the Venetians introduced stradioti into Italy in the late fifteenth century, they caused sensation among the condottieri and their warriors, principally because their tactics were so effective even against heavy cavalry. A number of military historians, including Paolo Iovio, Coriolano Cippico, Mario Sanudo, Erculi Riccoti, and Daniel E. Handy have described the activities of the stradioti in the West, and some military historians even attribute the reintroduction of light cavalry tactics in Western armies to the influence of the stradioti in Venetian armies."

- Galaty et al. 2013, p. 12: "Historical documents record the exploits of the stradiots, Albanian mercenaries who served throughout Western Europe (Millar 1976). We contend that the northern Albanian tribal system of feud and consequent emigration produced a ready pool of such mercenaries and was a flexible, adaptive strategy that encouraged resilience and long-term stability."

- Kondylis, 2006, p. 152: "Δεν είναι γνωστό από πότε η Βενετία ενσωμάτωσε στο στρατό της αυτούς τους οπλοφόρους. Πάντως, ήδη από το 1371, διατάγματα επέτρεπαν τη στρατολόγηση Ελλήνων των κτήσεων στον τοπικό στρατό" [It is unknown when Venice incorporated these armed men into its army. However, as early as 1371, decrees allowed Greeks to join the local army.]

- Birtachas 2018, p. 327.

- Birtachas 2018, pp. 327–328: "From studies on the provenance of their names it is deduced that about 80% of the stradiots were of Albanian and very few of Slav origin (Crovati). The remainder were Greek and, for the most part, captains (capitani di stradioti)."

- Nicolle, 2002: p. 16

- Floristán 2020, pp. 10–15, 15–28, 28–43, 233–236, 236–245, 245–252.

- Muhaj 2016b, pp. 32–33

- Setton 1976, p. 494; Nicolle & Rothero 1989, p. 16.

- Detrez & Plas 2005, p. 134.

- Detrez & Plas 2005, p. 134, Footnote #24.

- English Historical Review 2000, p. 192: "Western armies employed stradioti, Greek mercenary companies, as did Henry VIII against the Scots in 1514, where Harris might have further explored the testimony of Nicander Nucius and of PRO records."

- Kondylis, 2006, p. 171: "Οι Αλβανοί του Ναυπλίου ήταν εγκατεστημένοι έξω από την πόλη, ανάμεσα στο ανατολικό τείχος και στο λόφο του Παλαμηδίου, περιοχή που ονομαζόταν «teraglio et sasso»" [The Albanians of Nauplion settled outside of the city... "

- Kondylis, 2006, p. 156

- Korre 2018, p. 498: iii. Η γλώσσα, ένα ισχυρό κριτήριο ενσωμάτωσης - Οι stradioti ήταν πολύγλωσσοι, ιδιότητα που ήταν συνέπεια της μετακίνησής τους στο χώρο και σε άλλα περιβάλλοντα: αρβανίτικα (αλβανικά και ελληνικά στοιχεία σε μια υβριδική γλώσσα), τουρκικά και ιταλικά, είναι οι γλώσσες που εντοπίζονται. Το ελληνικό όμως γλωσσικό όργανο φαίνεται πως επικρατεί, ακόμα και στον πυρήνα ομοιογενών compagnie. Η compagnia του Γιώργη Λυκούρεσση στα Χανιά ήταν κυρίως ελληνόγλωσση παρότι αποτελούνταν αποκλειστικά από αρβανίτες. Σύμφωνα με τις βενετικές πηγές, οι ιππείς εκείνοι, πολύ περισσότερο αγρότες παρά μισθοφόροι stradioti, parlavano in greco.

- Nadin 2008, p. 59:Si tratta di un folto gruppo di mercenari che, per decenni e decenni presenti in suolo veneto, si distinsero per capacita e lealta e furono proprio loro ad imporre nell' immaginarion una identita "albanese"

- Pappas, 1991, p. 34: "Although the stradioti who settled in the West gradually lost contact with the Levant , they were instrumental in founding and maintaining Greek Orthodox and Uniate communities in Venice and other Italian and Dalmatian cities.

- Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue françoise, vol. 1

- Daniel R.P.G. (1724) Histoire de la milice francoise, et des changemens qui s'y sont ... , Amsterdam, vol. 1, pp. 166-171.

- Virol M. (2007) Les oisivetes de monsieur de Vauban, edition integrale, Champ Vallon, Seyssel, p. 988, footnote 3.

- La Grand Encyclopedie, Eole-Fanucci, Paris (undated), vol. 16, article "Argoulet"

- Hall, Edward, Chronicle (1809), p. 543, 550

- Bonaparte N. Études sur le passé et l'avenir de l'artillerie, Paris, 1846, vol. 1, p. 161

- Boyer Abel (1710) The history of the reign of Queen Anne, year the eight, London, p. 86. A list of French captured by the British at the battle of Tasnieres (1709) includes an officer of the "Royal Carabins"

- Monter 2007, p. 76.

- Alex N. Dragnich (1994). Serbia's Historical Heritage. East European Monographs. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-88033-244-6.

- Modern Greek Studies Association (1976). Hellenism and the first Greek war of liberation (1821–1830): continuity and change. Institute for Balkan Studies. p. 72.

- Historia del Rey Don Fernando el Catolico: De las empresas y ligas de Italia, book V, p. 3.

- LA GUARDIA REAL Archived 2010-11-28 at the Wayback Machine

- Higham 1972, p. 171: "The cost of hiring German pikemen, Spanish arquebusiers, Albanian horsemen and Italians led Henry VIII to ransack the monasteries to find money to pay them."

- Hammer 2003, p. 24: "In early September, the earl of Hertford simply marched into Scotland with 16,000 men, including 1000 heavily armoured knights and contingents of Albanian light cavalry and Spanish infantry."

- Nicander Nucius, The second book of the travels of Nicander Nucius of Corcyra, ed. by Rev. J.A. Cramer, 1841, London, p.90. See also Note 1.

- Moustoxydes Andreas (1856) Nikandros Noukios, in the periodical Pandora, vol. 7, No. 154, 15 Augh. 1856, p. 222 In Greek language.

Andreas Moustoxydes was a Greek historian and politician. - Howard 2009, p. 77.

- Downing 1992, p. 66.

- Nicolle & Rothero 1989, p. 36.

- Nicolle, David (2010). Cross and Crescent in the Balkans: The Ottoman Conquest of Southeastern Europe (14th – 15th Centuries). Pen & Sword Military. p. 193. ISBN 978-1-84415-954-3.

The tactics of most stradioti, whether Balkan or Byzantine, seem... perhaps this was a result of the overwhelmingly defensive character of Byzantine warfare by the fifteenth century

- DeCommines, Philippe, Lettres et Negotiations, with comments by Kervyn De Lettenhove, ed. 1868, V. Devaux et Cie. Bruxelles, vol. 2, p. 200, 220: "quinze cents estradiotes grecs ou albanais, "vaillans hommes" qui recevaient in ducat par tete d' ennemi qu'ils rapportaient a leurs chefs".

- Hoerder 2002, p. 63: "Throughout Europe footmen replaced knights, that is, cavalry. They used new weapons and came with regionally varying skills: English archers and crossbowmen, Swiss pikemen, Flemish burgher forces, and, later, Italian gunfighters or exiled Albanian and Greek stradioti on light horse (from Italian strada: street). Mercenaries hired on for pay under "military enterprisers" received wages only as long as work was available."

- Kondylis, 2006, p. 154: "οι stratioti φορούσαν στο κεφάλι περικεφαλαία 'casco'.

- Kondylis, 2006, p. 154

- Muhaj 2016a, p. 81: "Në Venecia quheshin edhe capelletti, për shkak të kësulave të vogla që mbanin. Në lidhje me formën e këtyre kësulave përshkrimet e autorëve përkojnë në atë që këto ishin shumë të ngjashme me kësulat e Labërisë shqiptare. Bëhet fjalë për kësulë në formë konike, me një zgjatje të vogël: “capelli aguzzi”."

- Gramaticopolo 2016, p. 43: "Questo berretto è da intendersi come un cappello a punta, rinforzato all'interno da più fogli di carta incollati assieme, il che garantiva una sorprendente resistenza".

- Zečević, Nada (2019). "Restoration, Reconstruction and Union: memories of home in the stratiot poetry of Antonio Molino". Radovi: Zavoda za Hrvatsku Povijest Filozofskoga Fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu. 51 (1): 164–65. doi:10.17234/RadoviZHP.51.8.

(...) the heroic poems of Tsanes Koronaios which glorify the famed Albanian commander of the Venetian army, Mercurio Bua (fl. late 15th − early 16th c.), the cycles of the oral tradition of Albanian stratiots in Southern Italy and Slavic peasant-fighters from Venetian Dalmatia (uskoci) – but also plays by Italian comedy writers that utilised the stratiot tradition to win the interest of their popular Italian audiences(...) local accounts on the famous 15th century stratiot figures such as Pietro Bua, the father of the widely popular Mercurio (d. by the early 1560s).

- Zorzi, Renzo; Cini.", Fondazione "Giorgio (2002). Le metamorfosi del ritratto (in Italian). L.S. Olschki. p. 164. ISBN 978-88-222-5147-3.

as the greek condottiere Mercurio Bua who was resident in Treviso

- Bugh, Glenn Richard (2002). "Andrea Gritti and the Greek Stradiots of Venice in the Early 16th Century". Thēsaurismata tou Hellēnikou Institoutou Vyzantinōn kai Metavyzantinōn Spoudōn: 93. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

In any case, there is no evidence to disprove Barbarigo's testimony that Teodoro Paleologo, 54 perhaps the most famous Greek stradiot – captain ( outside of Mercurio Bua )

- Romano, Roberto. "a produzione letteraria di Jacopo Trivolis, nobile veneto-corfiota" (PDF). Porphyra. p. 81. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

al capitano greco-albanese Mercurio Bua

- Vincent, Alfred (1 January 2017). "Byzantium after Byzantium? Two Greek Writers in Seventeenth-Century Wallachia". Byzantine Culture in Translation: 230. doi:10.1163/9789004349070_013. ISBN 9789004349070.

Merkourios Bouas (Bua), a Greek-Albanian from. Nafplio and commander of a force of stradiots, a light cavalry in Venetian service.

- Nicolle & Rothero 1989, p. 16

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Bembi, Petri (1551). Historiae Venetae. Venetiis: Apud Aldi Filios.Available online in Latin language.

- Bembo, Pietro (1780). Storia Veneta. Venice, Italy. In Italian language.

- De Commines, Philip (1901). Memoirs. first published in 1524.

- Battle of Fornovo: Memoirs, 1856 edition, London, vol. 2, p. 201.

Secondary sources

- Birtachas, Stathis (2018). "15 – Stradioti, Cappelletti, Compagnie or Milizie Greche: 'Greek' Mounted and Foot Mercenary Companies in the Venetian State (Fifteenth to Eighteenth Centuries)". A Military History of the Mediterranean Sea – Aspects of War, Diplomacy, and Military Elites. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-36204-8.

- Bugh, Glenn Richard (2002). Andrea Gritti and the Greek stradiots of Venice in the early 16th century. Vol. 32. Thesaurismata (Bulletin of the Istituto Ellenico di Studi Bizantini e Postbizantini di Venezia). pp. 81–94.

- Detrez, Raymond; Plas, Pieter (2005). Developing Cultural Identity in the Balkans: Convergence vs Divergence. Peter Lang. ISBN 90-5201-297-0.

- English Historical Review (2000). "Shorter Notice. Greek Emigres in the West, 1400–1520. Jonathan Harris". The English Historical Review. Oxford Journals. 115 (460): 192–193. doi:10.1093/ehr/115.460.192.

- Downing, Brian M. (1992). The Military Revolution and Political Change: Origins of Democracy and Autocracy in Early Modern Europe. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02475-8.

- Floria, B. N. (1978). "Vykhodtsy iz Balkanakh stran na russkoi sluzhbe". Balkanskia Issledovaniia 3, Osloboditel'nye Dvizheniia Na Balkanakh. Moscow: 57–63.

- Floristán, José M. (2019). "Stradioti albanesi al servizio degli Asburgo di Spagna (I): le famiglie albanesi Bua, Crescia e Renesi". Shêjzat – Pleiades (1–2): 3–46.

- Floristán, José M. (2020). "Estradiotes albaneses al servicio de los Austrias españoles (II): familias Alambresi, Basta, Capuzzimadi". Shêjzat – Pleiades (1–2): 232–260.

- Folengo, Teofilo; Mullaney, Ann E. (2008). Baldo, Books 13-15. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03124-1.

- Galaty, Michael; Lafe, Ols; Lee, Wayne; Tafilica, Zamir (2013). Light and Shadow: Isolation and Interaction in the Shala Valley of Northern Albania. The Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press. ISBN 978-1-931745-71-0.

- Gramaticopolo, Andrea (2016). Stradioti: alba, fortuna e tramonto dei mercenari greco-albanesi al servizio della Serenissima (in Italian). Soldiershop Publishing. ISBN 9788893270489.

- Hammer, Paul E. J. (2003). Elizabeth's Wars: War, Government, and Society in Tudor England, 1544–1604. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-91942-4.

- Higham, Robin D. S. (1972). A Guide to the Sources of British Military History. Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-7100-7251-1.

- Hoerder, Dirk (2002). Cultures in Contact: World Migrations in the Second Millennium. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-2834-8.

- Howard, Michael (2009). War in European History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-954619-0.

- Kondylis, Athanaios (2006). Το Ναύπλιο (1389–1540): μια ευρωπαϊκή πόλη στην ελληνο-βενετική Ανατολή. Didaktorika.gr (Thesis). University of Athens. hdl:10442/hedi/22368.

- Korre, Katerina (2018). Μισθοφόροι stradioti της Βενετίας: πολεμική και κοινωνική λειτουργία (15ος-16ος αιώνας) (Thesis) (in Greek). Greece: Ionian University.

- Minchella, Giuseppina (2015). Frontiere aperte: Musulmani, ebrei e cristiani nella Repubblica di Venezia (XVII secolo). Viella. ISBN 978-88-6728-532-7.

- Monter, E. William (2007). A Bewitched Duchy: Lorraine and its Dukes, 1477–1736. Librairie Droz. ISBN 978-2-600-01165-5.

- Muhaj, Ardian (2016a). "Roli dhe prania e luftëtarëve shqiptarë në Europën veriore në shek. XVI" [The Role and Presence of the Albanian Light Cavalry in Northern Europe in the 16th Century]. Studime Historike (1–2): 81–98. ISSN 0563-5799.

- Muhaj, Ardian (2016b). "Le origini economiche e demografiche dell'insediamento degli arbëreshë in Italia. Dal medioevo alla prima età moderna". Basiliskos: 21–34. ISBN 978-88-98432-16-5. ISSN 2284-2047.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1988). Byzantium and Venice: A Study in Diplomatic and Cultural Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-34157-4.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1994). The Byzantine Lady: Ten Portraits, 1250–1500. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-45531-6.

- Nicol, Donald MacGillivray (2002). The Immortal Emperor: The Life and Legend of Constantine Palaiologos, Last Emperor of the Romans. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-89409-3.

- Nadin, Lucia (2008). Migrazioni e integrazione: il caso degli Albanesi a Venezia (1479–1552). Bulzoni. ISBN 978-8878703407.

- Nicol, Donald MacGillivray (1968). The Byzantine Family of Kantakouzenos (Cantacuzenus) ca. 1100–1460: A Genealogical and Prosopographical Study. Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies, Trustees for Harvard University.

- Nicolle, David; McBride, Angus (1988). Hungary and the Fall of Eastern Europe 1000–1568. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 0-85045-833-1.

- Nicolle, David; Rothero, Christopher (1989). The Venetian Empire 1200–1670. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 0-85045-899-4.

- Pappas, Nicholas Charles (1991). Greeks in Russian Military Service in the Late Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries. Institute for Balkan Studies. p. 7.

The stratioti continued the Byzantine and Balkan traditions of cavalry warfare, which emphasized ambushes, hit-and-run assaults, feigned retreats, counterattacks and other tactics little known to western armies of the time. Indeed, when the Venetians introduced stradioti into Italy in the late fifteenth century, they caused sensation among the condottieri and their warriors , principally because their tactics were so effective even against heavy cavalry. A number of military historians, including Paolo Iovio, Coriolano Cippico, Mario Sanudo, Erculi Riccoti, and Daniel E. Handy have described the activities of the stradioti in the West, and some military historians even attribute the reintroduction of light cavalry tactics in Western armies to the influence of the stradioti in Venetian armies.

- Pappas, Nicholas C. J. "Stradioti: Balkan Mercenaries in Fifteenth and Sixteenth Century Italy". Sam Houston State University. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24.

- Sathas, Konstantinos (1867). Hellenika Anekdota (Volume 1) (in Greek). Available online

- Setton, Kenneth M. (1976). The Papacy and the Levant (1204–1571), Volume I: The Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society. ISBN 0-87169-114-0.

- Societa Italiana di Studi Araldici (2005). "Sul Tutto: Periodico della Societa Italiana di Studi Araldici, No. 3" (PDF).

- Tardivel, Louis (1991). Répertoire des emprunts du français aux langues étrangères (in French). Québec: Les éditions du Septentrion. ISBN 2-921114-51-8.

- Wright, Diana Gilliland (1999). Bartolomeo Minio: Venetian Administration in 15th-century Nauplion. Washington D.C.: The Catholic University of America.

Further reading

- Katerina B. Korrè, Stradioti, mercenaries of Venice: military and social role (XV-XVI centuries), PhD Thesis, Ionian University 2018 [Available, in Greek, on https://www.didaktorika.gr/eadd/handle/10442/42539] / Κορρέ Κατερίνα Β., Μισθοφόροι stradioti της Βενετίας: πολεμική και κοινωνική λειτουργία (15ος-16ος αιώνας), Διδακτορική Διατριβή, Ιόνιο Πανεπιστήμιο 2018

- Lopez, R. Il principio della guerra veneto-turca nel 1463. "Archivio Veneto", 5 serie, 15 (1934), pp. 47–131.

- Μομφερράτου, Αντ. Γ. Σιγισμούνδος Πανδόλφος Μαλατέστας. Πόλεμος Ενετών και Τούρκων εν Πελοποννήσω κατά 1463-6. Αθήνα, 1914.

- Sathas, K. N. Documents inédits relatifs à l' histoire de la Grèce au Moyen Âge, publiés sous les auspices de la Chambre des députés de Grèce. Tom. VI: Jacomo Barbarigo, Dispacci della guerra di Peloponneso (1465-6), Paris, 1880–90, pp. 1-116.

- Κορρέ Β. Κατερίνα,"Έλληνες στρατιώτες στο Bergamo. Οι πολιτικές προεκτάσεις ενός εκκλησιαστικού ζητήματος", Θησαυρίσματα 28 (2008), 289-336.

- Stathis Birtachas, «La memoria degli stradioti nella letteratura italiana del tardo Rinascimento», in Tempo, spazio e memoria nella letteratura italiana. Omaggio ad Antonio Tabucchi / Χρόνος, τόπος και μνήμη στην ιταλική λογοτεχνία. Τιμή στον Antonio Tabucchi, a cura di Z. Zografidou, Salonicco, Università Aristotele di Salonicco – Aracne – University Studio Press, 2012, pp. 124–142. Online: https://www.academia.edu/2770159/La_memoria_degli_stradioti_nella_letteratura_italiana_del_tardo_Rinascimento

- "Stradioti, Cappelletti, Compagnie or Milizie Greche: ‘Greek’ Mounted and Foot Troops in the Venetian State (Fifteenth to Eighteenth Centuries)", in A Military History of the Mediterranean Sea: Aspects of War, Diplomacy and Military Elites, eds. Georgios Theotokis and Aysel Yildiz, Leiden: Brill, 2018, pp. 325–346.

External links

Media related to Stratioti at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Stratioti at Wikimedia Commons