Swing (jazz performance style)

In music, the term swing has two main uses. Colloquially, it is used to describe the propulsive quality or "feel" of a rhythm, especially when the music prompts a visceral response such as foot-tapping or head-nodding (see pulse). This sense can also be called "groove". It is also known as shuffle.

The term swing, as well as swung note(s) and swung rhythm,[lower-alpha 2] is also used more specifically to refer to a technique (most commonly associated with jazz but also used in other genres) that involves alternately lengthening and shortening the first and second consecutive notes in the two part pulse-divisions in a beat.

Overview

Like the term "groove", which is used to describe a cohesive rhythmic "feel" in a funk or rock context, the concept of "swing" can be hard to define. Indeed, some dictionaries use the terms as synonyms: "Groovy ... denotes music that really swings."[1] The Jazz in America glossary defines swing as, "when an individual player or ensemble performs in such a rhythmically coordinated way as to command a visceral response from the listener (to cause feet to tap and heads to nod); an irresistible gravitational buoyancy that defies mere verbal definition."[2]

When jazz performer Cootie Williams was asked to define it, he joked, "Define it? I'd rather tackle Einstein's theory!"[3] When Louis Armstrong was asked on the Bing Crosby radio show what swing was, he said, "Ah, swing, well, we used to call it syncopation—then they called it ragtime, then blues—then jazz. Now, it's swing. Ha! Ha! White folks, yo'all sho is a mess."[4]

Benny Goodman, the 1930s-era bandleader nicknamed the "King of Swing", called swing "free speech in music", whose most important element is "the liberty a soloist has to stand and play a chorus in the way he feels it". His contemporary Tommy Dorsey gave a more ambiguous definition when he proposed that "Swing is sweet and hot at the same time and broad enough in its creative conception to meet every challenge tomorrow may present."[3] Boogie-woogie pianist Maurice Rocco argues that the definition of swing "is just a matter of personal opinion".[3] When asked for a definition of swing, Fats Waller replied, "Lady, if you gotta ask, you'll never know."[5]

Bill Treadwell stated:

What is Swing? Perhaps the best answer, after all, was supplied by the hep-cat who rolled her eyes, stared into the far-off and sighed, "You can feel it, but you just can't explain it. Do you dig me?"

— Treadwell (1946), p.10[6]

Stanley Dance, in The World of Swing, devoted the two first chapters of his work to discussions of the concept of swing with a collection of the musicians who played it. They described a kinetic quality to the music. It was compared to flying; "take off" was a signal to start a solo. The rhythmic pulse continued between the beats, expressed in dynamics, articulation, and inflection. Swing was as much in the music anticipating the beat, like the swing of a jumprope anticipating the jump, as in the beat itself.[5] Swing has been defined in terms of formal rhythmic devices, but according to the Jimmie Lunceford tune, "T'aint whatcha do, it's the way thatcha do it" (say it so it swings). Physicists investigating swing have noted that it coincides with a perceptible difference between the timing of a soloist and the rest of the performers.[7]

Swing as a rhythmic style

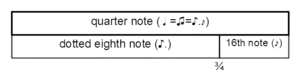

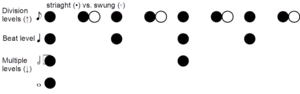

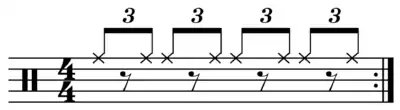

In swing rhythm, the pulse is divided unequally, such that certain subdivisions (typically either eighth note or sixteenth note subdivisions) alternate between long and short durations. Certain music of the Baroque and Classical era is played using notes inégales, which is analogous to swing. In shuffle rhythm, the first note in a pair may be twice (or more) the duration of the second note. In swing rhythm, the ratio of the first note's duration to the second note's duration can range: The first note of each pair is often understood to be twice as long as the second, implying a triplet feel, but in practice the ratio is less definitive and often much more subtle.[9] In traditional jazz, swing is typically applied to eighth notes. In other genres, such as funk and jazz-rock, swing is often applied to sixteenth notes.[10][11]

In most jazz music, especially of the big band era and later, the second and fourth beats of a 4/4 measure are emphasized over the first and third, and the beats are lead-in—main-beat couplets (dah-DUM, dah-DUM....). The "dah" anticipates, or leads into, the "DUM." The "dah" lead-in may or may not be audible. It may be occasionally accented for phrasing or dynamic purposes.

The instruments of a swing rhythm section express swing in various ways, which evolved as the music developed. During the early development of swing music, the bass was often played with lead-in—main-note couplets, often with a percussive sound. Later, the lead-in note was dropped but incorporated into the physical rhythm of the bass player to help keep the beat "solid” - the lead-in beats were not audible, but expressed in the player’s motion.

Similarly, the rhythm guitar was played with the lead-in beat strummed by the player, but so softly as to be nearly or completely inaudible.

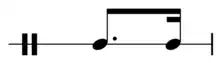

The piano was played with a variety of devices for swing: Chord patterns played in the rhythm of a dotted-eighth—sixteenth couplet were characteristic of boogie-woogie playing (sometimes also used in boogie-woogie horn section playing). The "swing bass" left hand, used by James P. Johnson, Fats Waller, and Earl Hines, used a bass note on the first and third beats, followed by a mid-range chord to emphasize the second and fourth beats. As with the bass, lead-in beats were not audible, but expressed in the motion of the left arm.

Swing piano also put the first and third beats in a role anticipatory to the emphasized second and fourth beats in two-beat bass figures.[14]

As swing music developed, the role of the piano in the ensemble changed to emphasize accents and fills; these were often played on the lead-in to the main beat, adding a punch to the rhythm. Count Basie's style was sparse, played as accompaniment to the horn sections and soloists.[15]

The bass and snare drums started the swing era as the main timekeepers, with the snare usually used for either lead-ins or emphasis on the second and fourth beats. It was soon found that the high-hat cymbal could add a new dimension to the swing expressed by the drum kit when played in a two-beat "ti-tshhh-SH" figure, with the "ti" the lead-in to the "tshhh" on the first and third beats, and the "SH" the emphasized second and fourth beats.

With that high-hat figure, the drummer expressed three elements of swing: the lead-in with the "ti," the continuity of the rhythmic pulse between the beats with the "tshhh," and the emphasis on the second and fourth beats with the "SH". Early examples of that high-hat figure were recorded by the drummer Chick Webb. Jo Jones carried the high-hat style a step further, with a more continuous-sounding "t'shahhh-uhh" two beat figure while reserving the bass and snare drums for accents. The changed role of the drum kit away from the heavier style of the earlier drumming placed more emphasis on the role of the bass in holding the rhythm.[15]

Horn sections and soloists added inflection and dynamics to the rhythmic toolbox, "swinging" notes and phrases. One of the characteristic horn section sounds of swing jazz was a section chord played with a strong attack, a slight fade, and a quick accent at the end, expressing the rhythmic pulse between beats. That device was used interchangeably or in combination with a slight downward slur between the beginning and the end of the note.

Similarly, section arrangements sometimes used a series of triplets, either accented on the first and third notes or with every other note accented to make a 3/2 pattern. Straight eighth notes were commonly used in solos, with dynamics and articulation used to express phrasing and swing. Phrasing dynamics built swing across two or four measures or, in the innovative style of tenor saxophonist Lester Young, across odd sequences of measures, sometimes starting or stopping without regard to place in the measure.[15]

The rhythmic devices of the swing era became subtler with bebop. Bud Powell and other piano players influenced by him mostly did away with left-hand rhythmic figures, replacing them with chords. The ride cymbal played in a "ting-ti-ting" pattern took the role of the high-hat, the snare drum was mainly used for lead-in accents, and the bass drum was mainly used for occasional "bombs." But the importance of the lead-in as a rhythmic device was still respected. Drummer Max Roach emphasized the importance of the lead-in, audible or not, in "protecting the beat."[16] Bebop soloists rose to the challenge of keeping a swinging feel in highly sophisticated music often played at a breakneck pace. The groundbreakers of bebop had come of age as musicians with swing and, while breaking the barriers of the swing era, still reflected their swing heritage.[15]

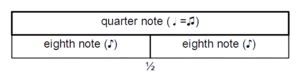

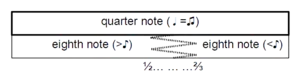

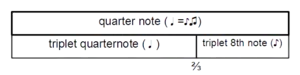

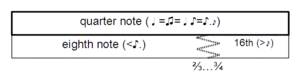

- Various rhythmic swing approximations:

- ≈1:1 = eighth note + eighth note, "straight eighths." ⓘ

- ≈3:2 = long eighth + short eighth. ⓘ

- ≈2:1 = triplet quarter note + triplet eighth, triple meter; ⓘ

- ≈3:1 = dotted eighth note + sixteenth note. ⓘ

The subtler end of the range involves treating written pairs of adjacent eighth notes (or sixteenth notes, depending on the level of swing) as slightly asymmetrical pairs of similar values. On the other end of the spectrum, the "dotted eighth – sixteenth" rhythm, consists of a long note three times as long as the short. Prevalent "dotted rhythms" such as these in the rhythm section of dance bands in the mid-20th century are more accurately described as a "shuffle";[17] they are also an important feature of baroque dance and many other styles.

In jazz, the swing ratio typically lies somewhere between 1:1 and 3:1, and can vary considerably. Swing ratios in jazz tend to be wider at slower tempos and narrower at faster tempos.[18] In jazz scores, swing is often assumed, but is sometimes explicitly indicated. For example, "Satin Doll", a swing era jazz standard, was notated in 4

4 time and in some versions includes the direction, medium swing.

Genres using swing rhythm

Swing is commonly used in swing jazz, ragtime, blues, jazz, western swing,[19] new jack swing,[20] big band jazz, swing revival, funk, funk blues, R&B, soul music, rockabilly, neo rockabilly, rock and hip-hop. Much written music in jazz is assumed to be performed with a swing rhythm. Styles that always use traditional (triplet) rhythms, resembling "hard swing", include foxtrot, quickstep and some other ballroom dances, stride piano, and 1920s-era novelty piano (the successor to ragtime style). In the Middle East, a rhythm very similar to shuffle is used in some forms of Iraqi, Kurdish, Azeri, Iranian and Assyrian dance music.[21]

See also

- Polyrhythm

- Swing music, a jazz-influenced genre of music

- Clave (rhythm) for the rhythms of Latin jazz and Latin dance

- Jig for the swung triplets of Celtic music – triplets with a swing feel to them – not to be confused with the swung duplets of "triplet swing".

- Folk hornpipe of the dotted note variety, often notated in 2

4 (The Harvest Home, The Boys of Bluehill) for the 3:1 hard swing/shuffle of Celtic music. - Notes inégales, a 17th-century French usage of similar meters and notation

Explanatory notes

References

- "Swing Slang". Big Bands Database Plus.

- "Jazz Resources: Glossary". Jazz in America. The Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz.

- "What Is Swing?". Savoy Ballroom.

- Argyle, Ray (1 April 2009). Scott Joplin and the Age of Ragtime. McFarland. p. 172 – via Internet Archive.

- Dance, Stanley, 1974, The World of Swing: An Oral History of Big Band Jazz (2001 edition) Da Capo Press, 436 p.

- Treadwell, Bill (1946). "Introduction: What Is Swing". Big Book of Swing. pp. 8–10.

- Godoy, Maria (2023-01-18). "What makes that song swing? At last, physicists unravel a jazz mystery". Morning Edition. NPR. Retrieved 2023-01-18.

- Savidge, Wilbur M.; Vradenburg, Randy L. (2002). Everything About Playing the Blues. Music Sales Distributed. p. 35. ISBN 1-884848-09-5.

- "Jazz Drummers' Swing Ratio in Relation to Tempo". Acoustical Society of America. Archived from the original on 2008-05-18. Retrieved 2008-07-22.

- Frane, Andrew V. (2017). "Swing rhythm in classic drum breaks from hip-hop's breakbeat canon". Music Perception. 34 (3): 291–302. doi:10.1525/mp.2017.34.3.291.

- Pressing, Jeff (2002). "Black Atlantic Rhythm. Its Computational and Transcultural Foundations". Music Perception. 19 (3): 285–310. doi:10.1525/mp.2002.19.3.285.

- Mattingly, Rick (2006). All About Drums. Hal Leonard. p. 44. ISBN 1-4234-0818-7.

- Starr, Eric (2007). The Everything Rock & Blues Piano Book. Adams Media. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-59869-260-0.

- Hadlock, Richard, Jazz Masters of the Twenties, New York, MacMillan, 1972, 255p.

- Russell, Ross, Jazz Style in Kansas City and the Southwest, Berkeley, CA, University of California Press, 1972, 291 p.

- Davis, Miles, and Troupe, Quincy, Miles: The Autobiography, New York, Simon and Schuster, 1989, 448 p.

- Prögler, J. A. (1995). "Searching for Swing: Participatory Discrepancies in the Jazz Rhythm Section". Ethnomusicology. 39 (1): 26. doi:10.2307/852199. JSTOR 852199.

- Friberg, Anders; Sundström, Andreas (2002). "Swing Ratios and Ensemble Timing in Jazz Performance: Evidence for a Common Rhythmic Pattern". Music Perception. 19 (3): 344. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.416.1367. doi:10.1525/mp.2002.19.3.333.

- Stomping the Blues. writer Albert Murray. Da Capo Press. 2000. page 109, 110. ISBN 978-0-252-02211-1, ISBN 0-252-06508-5

- "Teddy Riley New Jack Swing Hip Hop part 1". YouTube. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- Armbrust, Walter (2000). Mass Mediations: New Approaches to Popular Culture in the Middle East and Beyond. University of California Press. p. 70. ISBN 9780520219267.

Further reading

- Floyd, Samuel A. Jr. (1991). "Ring Shout! Literary Studies, Historical Studies, and Black Music Inquiry". Black Music Research Journal. 11 (2): 265–268. doi:10.2307/779269. JSTOR 779269. Featuring a socio-musicological description of swing in African American music.

- Rubin, Dave (1996). Art of the Shuffle. Hal Leonard. ISBN 0-7935-4206-5. An exploration of shuffle, boogie, and swing rhythms for guitar.

- Clark, Mike; Paul, Jackson (1992). Rhythm Combination. ISBN 0-7119-8049-7.

- Prögler, J. A. (1995). "Searching for Swing: Participatory Discrepancies in the Jazz Rhythm Section". Ethnomusicology. 39 (1): 21–54. doi:10.2307/852199. JSTOR 852199.

- Butterfield, Matthew W. "Why Do Jazz Musicians Swing Their Eighth Notes?" (PDF). Yale University.

External links

- Video Resources – Swung Notes – more Swing Rhythm videos made with Bounce Metronome which can play swing rhythms

- "Jeff Porcaro", Drummer World. The "Rosanna shuffle" as played by the Toto drummer, including audio and transcription.

- Bernard Purdie breaks down "The Purdie Shuffle"

- YouTube video by pianist Greg Spero on Swing Demystified