Streckfus Steamers

Streckfus Steamers was a company started in 1910 by John Streckfus Sr. (1856–1925) born in Edgington, Illinois. He started a steam packet business in the 1880s, but transitioned his fleet to the river excursion business around the turn of the century. In 1907, he incorporated Streckfus Steamers to raise capital and expand his riverboat excursion business. A few years later, the firm acquired the Diamond Jo Line, a steamboat packet company.

| Type | River excursions |

|---|---|

| Industry | Entertainment |

| Predecessor | Acme Packet Company |

| Founded | 1910 in St. Louis, Missouri, United States |

| Founder | John Streckfus Sr. |

| Fate | Operated through 1978 |

| Successor | Streckfus Steamers, Incorporated |

| Headquarters | St. Louis |

Area served | Mississippi and Ohio Rivers |

Key people | Joseph Streckfus, Roy Streckfus, Vern Streckfus, John Streckfus Jr., William Carroll, Fate Marable |

| Owners | John Streckfus Sr., Joseph Streckfus |

The most active period started after the first World War. Bandleader Fate Marable recruited many musicians from New Orleans during this period, including Louis Armstrong. Streckfus Steamers expanded the number of excursion boats, acquired or converted larger boats, and hired more bands. After the death of the patriarch in 1925, the eldest son Joseph took over the company, and was assisted by his three brothers.

Family history

The principal of Streckfus Steamers was John Streckfus Sr., the son of Balthazar (1811–1881) and Anna Mary (Schaab) Streckfus, both immigrants to the United States from Bavaria. In 1850, the couple sailed for the United States with their two daughters, Barbara and Catherine. Before their ship arrived in New Orleans, Theresa gave birth to their first son, Michael. The Streckfus family eventually settled in Edgington, Illinois, but Balthazar later established his wagon shop in nearby Rock Island, Illinois in 1868. The family also had a grocery business.[1] John Streckfus married Theresa Bartemeier in 1880. Theresa bore nine children, and all of the surviving children worked on the riverboats.[2] Balthazar had been commuting from Edgington to his shop in Rock Island. His sons built a house for him in the late-1860s to facilitate a shorter journey to work. The Streckfus House still stands at 908 4th Avenue (as of October 2017), and the brick Italianate house has been designated as a Rock Island Landmark.[3]

John and Theresa Streckfus had four sons who were later licensed as captains: Joseph Leo (1887–1960), Roy Michael (1888–1968), John Nicholas (1891–1948), and Verne Walter (1895–1984). Joseph took over Streckfus Steamers in 1925 after the death of his father. Of this second Streckfus generation, he also was the most engaged with the music side of the business.[4]

There are at least two descendants of the Streckfus family who are active as river boat captains, at least through 2005. At that time, Captain Lisa Streckfus piloted the Delta Queen on the Mississippi River. She is the daughter of riverboat captain, Bill Streckfus, and great-granddaughter of the family's first riverboat captain, John Streckfus Sr. Lisa's cousin, Sister Mary Manthey, is also a Mississippi River steamboat captain.[5]

Packet service

John Streckfus bought his first steamboat in 1889 for $10,000. Verne Swain, a small steamer, measuring just 120-feet in length and 22-feet in width, was constructed in Stillwater, Minnesota at the Swain Shipyard.[6] Verne Swain ran every day with several stops between Davenport and Clinton Iowa, making a three-hour, one-way trip, then departed Clinton in the afternoon and returned to Davenport every evening. The steamer featured a narrow profile of just 22-feet, but was 120-feet in length. By 1891, Streckfus had acquired his own operator’s license and the title of Captain, whereas before, he had contracted for established operators to manage his steamers, and later he earned an engineer’s license. The same year, he bought his second steamboat, the Freddie,[2] a triple-decked, 73-foot sternwheeler with a 16-foot beam.[7] He transported freight and passengers on both the Mississippi and the Ohio Rivers, though eventually, he ran his packets on the Mississippi, north of St.Louis. Though he gained a reputation for punctuality and efficiency, he complained about the meager profits his packets earned running freight on the rivers.[8]

Early excursion service

By 1901, Streckfus changed his business model. Rather than using his slow paddle-wheelers to compete with the railroads for the freight business, he started transitioning to the excursion business. He tested this idea around 1900 when he installed a calliope on the City of Winona. The next year he increased his investment in the new venture with $25,000 in capital to convert a packet into a floating entertainment venue. According to his own design, Streckfus commissioned work on a 175-foot steamboat with a capacity to hold 2,000 passengers, sleeping berths for the crew and the entertainers, a 100 x 27 foot maple dance floor, a bar, a dining room, and electric lights. His first custom-built excursion boat he named the J.S.[9] Howard Shipyard of Jeffersonville, Indiana built the steamboat according to this new design.[2]

J.S. was the first steamboat in service on the Mississippi built especially for excursions. The 1901 excursions on the J.S. also corresponds to the first regular dance bands hired by Streckfus. Though the J.S. spent much of its time in St. Louis and St. Paul, it tramped on the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers.[10] While cruising the Mississippi near LaCrosse, WI on the night of June 25, 1910, Streckfus lost his custom-built steamer, the J.S., to a fire allegedly ignited by a drunken and disorderly passenger.[11] Streckfus started offering passenger service on his paddle-wheelers as a part of a new business model, balancing his business between moving freight and moving people.

Reorganization

John Streckfus organized the Streckfus Steamers Line in order to raise capital for an expansion of his steamboat excursion business. This was a closely held company, accepting investments only from members of the Streckfus family. He had started as a freight hauler who had sold passenger tickets, but his new company's main business was the excursion trade, though he also accepted freight about his steamboats.

The Diamond Jo Line

Moving freight on steamboats had already been dying as a business for a few decades, but this extended an opportunity. Since the packet business was unprofitable, this implied that many steamboat owners were motivated sellers. John Streckfus, who had seen his custom-built J.S. go up in flames, purchased a packet fleet from the Diamond Jo Line. He applied new capital raised by Streckfus Steamers to purchase of four ships. These included the Dubuque and three damaged riverboats: Sidney, a 221-foot sternwheeler; St. Paul, a 300-foot side-wheeler; and another side-wheeler, the 264-foot Quincy.[12] Included in this February 3, 1911 acquisition were docks, shipyards and warehouses. Streckfus Steamers paid $200,000 for all of these ships and land-based assets.[13]

Low water on the Mississippi River often sidelined the erstwhile packets for the next five seasons, but Streckfus bided his time by more bond issues and stock sales. He and his sons converted the St. Paul, which was fitted to run excursions between by 1917, when it tramped between St. Louis and St. Paul.[12] However, Streckfus business was executed at an inconvenient time: the Mississippi River was low due to droughts, and he would not be able to run regular excursions for about five years. Some years later, by the 1920s, the Streckfus patriarch had four sons to captain his fleet: Joseph, Vern, Roy, and John Streckfus Jr.[10]

SS St. Paul

John Streckus chose for his first conversion the largest of the Diamond Jo steamers, the 300-foot St. Paul. The company ran the first excursion for the St. Paul in 1917, and the next year it tramped between St. Louis and its namesake city on the Mississippi. The cabin was fitted with electric lights and fans. In its third season, the steamer ran aground on a sandbar, though this may have been the only mishap of the season. During the 1920s, Streckfus tramped it a bit further south, between the Quad Cities and Cape Girardeau, Missouri areas. The next decade, the large steamer plied the Ohio River until its 1930 rebuild. Rechristened Senator, it ran excursions for just a few more years.[14]

J.S. Deluxe

In 1919, Streckfus Steamers executed the second conversion from their Diamond Jo fleet, the packet Quincy. The company developed different ships for different markets, and the J.S. Deluxe catered to wealthy people from St. Louis. The company hired white musicians to perform on this steamer. J.S. Deluxe continued to serve the upscale market in the St. Louis area until the President took over in 1934.[15]

Capitol

The Capitol was born from the old sternwheeler, the Dubuque. It did not require as much water depth as other ships in their fleet, so Streckfus Steamers put it into use in the Upper Mississippi, while it served local cruises at New Orleans in the winter.[15] Fate Marable performed on the Capital starting in 1920, leading a band which included Louis Armstrong, Boyd Adkins, Norman Brashear, Warren “Baby” Dodds, David Jones, Henry Kimball, and Johnny St. Cyr.[16] Starting around 1924, the trumpeter Ed Allen led the Whispering Gold Band aboard the S.S. Capitol and stayed with Streckfus Steamers for about two years before moving to New York City.[17] “Papa” Celestine brought his band to the Capitol around 1926.[18] Sidney Desvigne who had previously played corner in Ed Allen’s band aboard the Capitol, left Streckfus Steamers for two years to lead his own band on the Island Queen. He returned to Streckfus Steamers, this time as a bandleader of the Sidney Desvigne’s S.S. Capitol Orchestra.[19] Walter “Fats” Pinchon followed Sidney Desvigne to the Island Queen and back. Eventually, the conservatory-trained pianist headed his own group, the last New Orleans band to have regular employment with Streckfus Steamers.[20]

Sidney

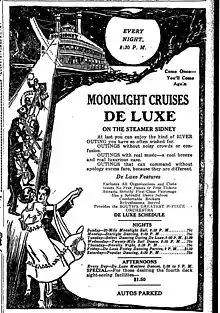

The Sidney is a steamboat first built in West Virginia between 1880 and 1881. On March 10, 1881, a breach in the steam line scalded fourteen people and killed four others. Diamond Jo Line acquired the steamer the next year for about $23,000, after which it ran the Mississippi River between St. Louis and St. Paul.[21]

Streckfus purchased the Sidney in 1911, a 221-foot sternwheeler from the Diamond Jo Line after the steam packet had been damaged by rocks while cruising on the Mississippi River. After repairs and refitting, he assigned the Sidney to winter excursions in the New Orleans area for about a decade. There was a 1921 rebuild, after which it was rechristened Washington.[22] Louis Armstrong performed aboard Sidney; Erroll Garner performed aboard Washington.[23] Fate Marable started his first New Orleans band on the Sidney in 1918, starting his expanded responsibilities as bandleader and talent scout, duties he would continue until his retirement in 1940. He scouted and hired Louis Armstrong, as well as Warren “Baby” Dodds, George “Pops” Foster, and Johnny St. Cyr.[24]

Later acquisitions

By the late-1930s, Streckfus Steamers had an inventory of aging steamboats with wooden hulls. The United States Coast Guard was enforcing stricter standards for riverboats, so the company built its last two excursion boats—the President and the SS Admiral—with steel hulls.[25]

President

In 1933, Streckfus Steamers bought the steamboat Cincinnati, a steel-hulled packet built in 1924. Cincinnati, true to its name, ran freight between the Queen City and Louisville, Kentucky. The company installed twenty-four watertight compartments into the existing steel hull and rebuilt a superstructure in steel, and expanded to five decks. The new excursion steamer was dubbed President, and Streckfus Steamers dispatched it up the Ohio River to serve Pittsburgh during the depression. Eventually, President replaced the J.S. Deluxe for excursions catering to wealthy people in the St. Louis market.[26] The ship commenced carrying excursion passenger in July 1934 out of St. Louis, with bands led by Fate Marable and Charlie Creath.[27] The S.S. President could accommodate 3,100 passengers and continued service for many years after riverboat excursions diminished in popularity after World War II. It was a venue for the New Orleans Jazz Festival, and hosted performers such as Pete Fountain and Louis Cottrell’s Dixieland Jazz Band.[28] In 1944, Streckfus Steamers moved the President from St. Louis to New Orleans. The company overhauled the President’s motive power, switching to diesel propulsion in 1978, before selling the ship to the New Orleans Steamboat company in 1981.[27]

SS Admiral

The SS Admiral was the first of the Streckfus fleet to be built with a metal superstructure on a steel hull. Originally the 1907 Albatross, a railroad ferry, Streckfus Steamers stripped it down to the steel hull and rebuilt it with a steel superstructure and an Art Deco finish. The company docked on the Mississippi River in St. Louis, at the foot of Washington Avenue.[29] SS Admiral commenced excursions in 1940, featuring an air-conditioned cabin and a large ballroom with maple flooring. The top deck, also known as the fifth deck, allowed guests to access close-up views of the riverbank sights through coin-operated telescopes.[30] In 1973, the company removed the steam engine and converted SS Admiral to diesel power. Streckfus Steamers ran excursions on the SS Admiral through the 1978 season, and retired the ship in 1979 due to weakness in its hull. The company sold the ship to John E. Connelly in 1981.[31]

Riverboat jazz

Early riverboat music

.jpg.webp)

John Streckfus started hiring musicians in 1901, when he engaged a friend to scout talent, which resulted in the first live musical entertainment, an African-American trio from Des Moines playing banjo, guitar, and mandolin. By 1903, Streckfus employed a house band to play popular music, a quartet which included a drummer, trumpeter, violinist, and a pianist. Charles Mills was the piano player, an African-American performing with three white musicians.[10] Mills remained with Streckfus until 1907, when he planned to seek musical opportunities in New York City. Mills told Fate Marable about his plans. The seventeen year-old piano player from Paducah, Kentucky solicited employment from an agent of the company when a Streckfus excursion boat docked in his hometown. Streckfus hired Marable to play a steam calliope and to play piano in the boat’s dance bands.[32] Marable first played piano for Streckfus on the J.S., playing in a duo with Emil Flindt, a white violist. Marable continued as a performer on the company's flagship until its conflagration in 1910.[10] The calliope was not just a musical instrument, it was an advertising medium for Streckfus Steamers. Its music carried for miles, announcing the presence of an excursion boat plying the river. People gathered at the docks, listening the calliope playing and some bought excursion tickets. Later, Streckfus allowed Marable to hire his own musicians. Around 1918, Marable assembled his own orchestra for the Sidney, including many from New Orleans: George "Pops" Foster (bass), Warren "Baby" Dodds (drums), Johnny St. Cyr (banjo), David Jones and Norman Mason (saxophone), Lorenzo Brashear (trombone), and Boyd Atkins (violin).[33]

After World War I

John Streckfus Sr. and his two brothers were amateur musicians and formed specific ideas about what kind of music his guests would hear. Often, one of the brothers attended rehearsals, marking the tempo with a watch to ensure 60 beats per minute for the slow tunes, and 90 beats per minute for the fast ones. While Louis Armstrong played for Fate Marable's band, he observed Joseph Streckfus smiling, laughing, and tapping to the beat.[34] However, another account indicates that Joseph Streckfus made music evaluations with considerations beyond his own sense of taste. According to trumpeter Henry “Red” Allen, Joseph Streckfus expected different tempi depending on where they played: St. Louis dancers liked a faster beat than the dancers in New Orleans.[35]

John Streckfus demanded strict decorum on his steamships. Though he sold alcoholic drinks, he tolerated neither gambling nor drunkenness from his passengers or his musicians. Marable made a perfect fit as a bandleader since he enforced these rules, and he imposed the same exacting standards for studying, rehearsing, and playing music. Marable sometimes took extreme measures to make a point, as when he fired musicians. Sometimes he left a hatchet on a musician's chair, in order to him know that "he gave them the axe." Another trick was telling the whole group (except for one musician) to come to rehearsal an hour early.[33] Musicians on Streckfus Steamers did not achieve star status during their tenure. John Streckfus established a policy of standard wages. At one point, he offered band members $35 per week, plus room and board (or $65 per week without room and board). He lowered compensation in 1919 to $37.50 per week—non-inclusive of room and board—albeit with much shorter work schedules. Seven years later, the company increased pay to $45 per week and added $5 weekly retention bonuses, but without room and board.[36] A few exceptional musicians were allowed to improvise for a few bars. One exception was Louis Armstrong. The Streckfus family and Marable otherwise insisted that the performers play the arrangements as written. However, this prompted expressive and gifted musicians like Armstrong to advance his career elsewhere.

In the period after World War I, John Streckfus followed the expansion of Jim Crow practices, segregating his musicians and his passengers. In 1920, Streckfus Steamers began running Monday night cruises for African-American audiences out of St. Louis.[37] On the other hand, according to Louis Armstrong, Fate Marable’s band was the first African American group to play music on the Mississippi riverboats.[38]

In Popular Culture

Mississippi River lore and riverboat culture feature prominently in the music of John Hartford. A former Streckfus musician (and later chief engineer of the Delta Queen) Mike O’Leary is the subject of Hartford's song "Let Him Go on Mama" on the Grammy-winning Mark Twang album (1976).[39]

References

- William Howland Kenney (2005). Jazz on the River. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 14.

- Annie Amantea Blum (2017). "Introduction". The Steamer Admiral. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing.

- "Streckfus House (Balthazar Streckfus)". Rock Island, Illinois. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- Kenney (2005), p. 15, 23.

- Bill Wundram (10 November 2005). "A river runs through Streckfus family lineage". Quad-Cities Times. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- Annie Amantea Blum (2017). "Chapter 1.". The Steamer Admiral. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing.

- Frederick Way Jr. (1994). Way's Packet Directory, 1848–1994. Revised. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press. p. 173.

- Kenney (2005), pp. 15–16.

- Kenney (2005), pp. 16–17.

- David Chevan (1989). "Riverboat Music from St. Louis and the Streckfus Steamboat Line". Black Music Research Journal. JSTOR. 9 (2).

- Kenney (2005), pp. 18–19.

- Kenney (2005), p. 19.

- "Diamond Jo Line". Encyclopedia Dubuque. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- Kenney (2005), pp.19–20.

- Kenney (2005), p. 20.

- "Marable's New Orleans band on the S.S. Capitol". Riverboats & Jazz. University of Tulane. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- "Ed Allen's Band on the S.S. Capitol". Riverboats & Jazz. University of Tulane. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- "Celestin's Original Tuxedo Jazz Orchestra". Riverboats & Jazz. University of Tulane. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- "Sidney Desvigne's S.S. Capitol Orchestra". Riverboats & Jazz. University of Tulane. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- "Walter "Fats" Pinchon's Band on the S.S. Capitol". Riverboats & Jazz. University of Tulane. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- "Sidney (Packet/Excursion, 1880-1921)". UW La Crosse Historic Steamboat Photographs. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- Kenney (2005), pp. 19–21.

- Kenney (2005), p. 80.

- "Fate Marable's Band on the S.S. Sidney". Riverboats & Jazz. University of Tulane. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Kenney (2005), p. 26.

- Kenney (2005), pp. 22–23.

- "The S. S. President". Riverboats & Jazz. University of Tulane. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- "Dance Floor of the President". Riverboats & Jazz. University of Tulane. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Annie Amantea Blum (2017). "Chapter 2". Steamer Admiral. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing.

- Annie Amantea Blum (2017). "Chapter 7". Steamer Admiral. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing.

- Annie Amantea Blum (2017). "Chapter 8". Steamer Admiral. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing.

- Kenney (2005), p. 38.

- Laurence Bergreen (1997). Louis Armstrong: An Extravagant Life. New York: Broadway Books. p. 145–150.

- Bergreen, pp. 150–153.

- Dennis Owsley (2006). City of Gabriels: The History of Jazz in St. Louis, 1895-1973. St. Louis: Reedy Press. p. 20. ISBN 9781933370040.

- Kenney, pp. 79–80.

- Owsley (2006), p. 21.

- Kenney (2005), p. 57.

- "The River: 'Geetars and mouth harps' were part of the river journey, and then there was also John Hartford | NKyTribune". Retrieved 2 December 2022.

Further reading

- Meyer, Dolores (1967). "Excursion Steamboating on the Mississippi with Streckfus Steamers, Inc." (St. Louis: St. Louis University) unpublished dissertation. Available at the Herman T. Pott National Inland Waterways Library, a special collection sponsored by the St. Louis Mercantile Library Association.

External links

- Riverboats and Jazz. Tulane University, Howard-Tilton Memorial Library.

- The Streckfus Steamboat Line. Tulane University, Riverboats & Jazz.

- The Streckfus Excursion Boats. Online Steamboat Museum

- A Brief Look at American Riverboat Musical Styles. University of Arkansas-Little Rock

- A Guide to the William F. and Betty Streckfus Carroll Collection. The St. Louis Mercantile Library Association, 2010.

- J. S. Deluxe (steamboat) Indiana Memory Digital Collections