Stress incontinence

Stress incontinence, also known as stress urinary incontinence (SUI) or effort incontinence is a form of urinary incontinence. It is due to inadequate closure of the bladder outlet by the urethral sphincter.

| Stress incontinence | |

|---|---|

| |

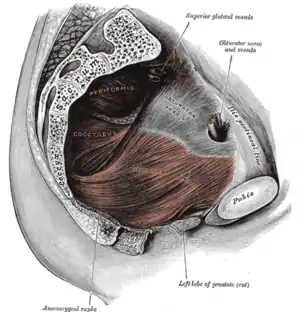

| Pelvic floor | |

| Specialty | Urology, gynaecology, urogynecology |

Pathophysiology

It is the loss of small amounts of urine associated with coughing, laughing, sneezing, exercising or other movements that increase intra-abdominal pressure and thus increasing the pressure on the bladder. The urethra is normally supported by fascia and muscles of the pelvic floor. If this support is insufficient due to any reason, the urethra would not close properly at times of increased abdominal pressure, allowing urine to pass involuntarily.

Most lab results such as urine analysis, cystometry and post-void residual volume are normal.

Some sources distinguish between urethral hypermobility and intrinsic sphincter deficiency. The latter is more rare, and requires different surgical approaches.[1]

Men

Stress incontinence in men is most commonly seen after prostate surgery,[2] such as prostatectomy, transurethral resection of the prostate, laparoscopic prostatectomy, or robotic prostatectomy.

Women

In women pregnancy, childbirth, obesity, and menopause often contribute to stress incontinence by causing weakness to the pelvic floor or damaging the urethral sphincter, leading to its inadequate closure, and hence the leakage of urine.[3][4][5] Stress incontinence can worsen during the week before the menstrual period. At that time, lowered estrogen levels may lead to lower muscular pressure around the urethra, increasing chances of leakage. The incidence of stress incontinence increases following menopause, similarly because of lowered estrogen levels. In female high-level athletes, effort incontinence may occur in any sports involving abrupt repeated increases in intra-abdominal pressure that may exceed perineal floor resistance.[6]

Treatment

Medications

Medications are not recommended for those with stress incontinence.[7]

Behavioral changes (conservative treatments)

Some behavioral changes can improve stress incontinence. It is recommended to decrease overall consumption of liquids and avoid drinking caffeinated beverages because they irritate the bladder. Spicy foods, carbonated beverages, alcohol and citrus also irritate the bladder and should be avoided. Quitting smoking can also improve stress incontinence because smoking irritates the bladder and can induce coughing (putting stress on the bladder). The effectiveness of these approaches to treat people for whom synthetic midurethral tape surgery did not result in a cure (failed surgery) is not clear.[8]

Results of a 2019 systematic review of urinary incontinence in women found that most individual, active treatments are better than no treatment.[9] Behavioral therapy, alone or combined with other interventions such as hormones, is generally more effective than other treatments alone.[10]

Exercises

One of the most common treatment recommendations includes exercising the muscles of the pelvis. Kegel exercises to strengthen or retrain pelvic floor muscles and sphincter muscles can reduce stress leakage.[11] Patients younger than 60 years old benefit the most.[11] The patient should do at least 24 daily contractions for at least 6 weeks.[11] It is possible to assess pelvic floor muscle strength using a Kegel perineometer.

Bladder training

Bladder training is a technique that encourages people to modify their voiding habits (lengthening the time between voiding). Weak evidence suggests that bladder training may be helpful for the treatment of urinary incontinence.[12] This type of intervention can take a person months to learn and would not be a therapy option for people who are not physically or mentally able to control their voiding.[12]

Incontinence pads

An incontinence pad is a multi-layered, absorbent sheet that collects urine resulting from urinary incontinence. Similar solutions include absorbent undergarments and adult diapers. Absorbent products may cause side effects of leaks, odors, skin breakdown, and UTI. Incontinence pads may also come in the form of a small sheet placed underneath a patient in the hospital, for situations when it is not practical for the patient to wear a diaper.

People have different preferences regarding the type of pad they use to stay dry when they have incontinence.[13] In addition, the effectiveness of incontinence pads differ between people.[13] Using different designs depending on the activity (sleeping/going out/staying in) is recommended.[13] For men, the most cost-effective design is an incontinence pad in a diaper format.[13] For women, incontinence pads that are in the form of disposable pull-ups are generally preferred, however there is a higher cost associated with this type of solution.[13] For women who are in nursing homes, diapers are preferred at night.[13] Washable diapers are cost effective, however, most people do not prefer washable diapers with the exception of some men who prefer as a means to control incontinence at night.[13] There is no evidence that one type of incontinence pad is superior with regard to skin health.[13]

Pessaries

A pessary is a medical device that is inserted into the vagina. The most common kind is ring shaped, and is typically recommended to correct vaginal prolapse. The pessary compresses the urethra against the symphysis pubis and elevates the bladder neck. For some women this may reduce stress leakage, however it is not clear how well these mechanical devices help women with stress urinary incontinence.[14]

Surgery

Doctors usually suggest surgery to alleviate incontinence only after other treatments have been tried. Many surgical options have high rates of success. Less-invasive variants of the sling operation have been shown to be equally effective in treating stress incontinence as surgical sling operations.[15] One such surgery is urethropexy. Insertion of a sling through the vagina (rather than by opening the lower abdomen) is called intravaginal slingplasty (IVS).

Slings

The procedure of choice for stress urinary incontinence in females is what is called a sling procedure. A sling implant usually consists of a synthetic mesh material in the shape of a narrow ribbon but sometimes a biomaterial (bovine or porcine) or the patients own tissue that is placed under the urethra through one vaginal incision and two small abdominal incisions. The idea is to replace the deficient pelvic floor muscles and provide a backboard of support under the urethra. Transvaginal mesh has recently come under scrutiny due to controversy relating to the Food and Drug Administration. Initially, the FDA approved implantable mesh devices due to their similarity to earlier prototypes, known as the 510(k) process.[16][17] As patients allege long-term harm and suffering as a result of implanted mesh; the FDA released a safety communication in 2008, and led to the reclassification of surgical mesh to a class 3 or high risk device in January 2016[18]. Insertion of a sling through the vagina (rather than by opening the lower abdomen) is called intravaginal slingplasty (IVS).

Transobturator tape

The transobturator tape (TOT or Monarc) sling procedure aims to eliminate stress urinary incontinence by providing support under the urethra. The minimally-invasive procedure eliminates retropubic needle passage and involves inserting a mesh tape under the urethra through three small incisions in the groin area.[19]

Midurethral tape

A procedure that involves placing polypropylene tape under the outlet from the bladder to improve stress incontinence.[8]

Bladder repositioning

Most stress incontinence in women results from the urethra dropping down toward the vagina. Therefore, common surgery for stress incontinence involves pulling the urethra up to a more normal position. Working through an incision in the vagina or abdomen, the surgeon raises the urethra and secures it with a string attached to muscle, ligament, or bone. For severe cases of stress incontinence, the surgeon may secure the urethra with a wide sling. This not only holds up the bladder but also compresses the bottom of the bladder and the top of the urethra, further preventing leakage.

Peri/trans urethral injections

A variety of materials have been historically used to add bulk to the urethra and thereby increase outlet resistance. This is most effective in patients with a relatively fixed urethra. Blood and fat have been used with limited success. The most widely used substance, gluteraldehyde crosslinked collagen (GAX collagen) proved to be of value in many patients. The main downfall was the need to repeat the procedure over time.

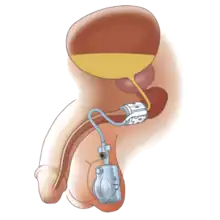

Artificial urinary sphincter

Another procedure to treat incontinence is the use of an artificial urinary sphincter, more used in men than in women. In this procedure, the surgeon enters and wraps the cuff of the artificial urinary sphincter around the urethra, in the same manner a blood pressure cuff wraps around your arm. The device includes a pump implanted under the skin that, when pressed by the patient, loosens the cuff, allowing for free urination. After that, the artificial sphincter automatically regains its pressure, closing the urethra again, and providing proper continence.[20]

Acupuncture

No useful studies have been done to determine whether acupuncture can help people with stress urinary incontinence.[21]

See also

References

- Ghoniem, G. M.; Elgamasy, A.-N.; Elsergany, R.; Kapoor, D. S. (18 March 2014). "Grades of Intrinsic Sphincteric Deficiency (ISD) Associated with Female Stress Urinary Incontinence". International Urogynecology Journal. 13 (2): 99–105. doi:10.1007/s001920200023. PMID 12054190. S2CID 29667668.

- Nitti, Victor W (2001). "The Prevalence of Urinary Incontinence". Reviews in Urology. 3 (Suppl 1): S2–S6. ISSN 1523-6161. PMC 1476070. PMID 16985992.

- Subak, Leslee L.; Richter, Holly E.; Hunskaar, Steinar (December 2009). "Obesity and urinary incontinence: epidemiology and clinical research update". The Journal of Urology. 182 (6 Suppl): S2–7. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2009.08.071. ISSN 1527-3792. PMC 2866035. PMID 19846133.

- Rortveit, G.; Hannestad, Y. S.; Daltveit, A. K.; Hunskaar, S. (December 2001). "Age- and type-dependent effects of parity on urinary incontinence: the Norwegian EPINCONT study". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 98 (6): 1004–1010. doi:10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01566-6. ISSN 0029-7844. PMID 11755545. S2CID 20932466.

- Lukacz, Emily S.; Lawrence, Jean M.; Contreras, Richard; Nager, Charles W.; Luber, Karl M. (June 2006). "Parity, mode of delivery, and pelvic floor disorders". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 107 (6): 1253–1260. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000218096.54169.34. ISSN 0029-7844. PMID 16738149. S2CID 1399950.

- Crepin, G; Biserte, J; Cosson, M; Duchene, F (October 2006). "Appareil génital féminin et sport de haut niveau" [The female urogenital system and high level sports]. Bulletin de l'Académie Nationale de Médecine (in French). 190 (7): 1479–91, discussion 1491–3. doi:10.1016/S0001-4079(19)33208-X. PMID 17450681.

- Qaseem A, Dallas P, Forciea MA, Starkey M, Denberg TD, Shekelle P (September 2014). "Nonsurgical management of urinary incontinence in women: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians". Annals of Internal Medicine. 161 (6): 429–440. doi:10.7326/m13-2410. PMID 25222388. Recommendation 4

- Bakali, Evangelia; Johnson, Eugenie; Buckley, Brian S; Hilton, Paul; Walker, Ben; Tincello, Douglas G (2019-09-04). Cochrane Incontinence Group (ed.). "Interventions for treating recurrent stress urinary incontinence after failed minimally invasive synthetic midurethral tape surgery in women". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (9): CD009407. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009407.pub3. PMC 6722049. PMID 31482580.

- Balk, Ethan M.; Rofeberg, Valerie N.; Adam, Gaelen P.; Kimmel, Hannah J.; Trikalinos, Thomas A.; Jeppson, Peter C. (2019). "Pharmacologic and Nonpharmacologic Treatments for Urinary Incontinence in Women: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis of Clinical Outcomes". Annals of Internal Medicine. 170 (7): 465–480. doi:10.7326/M18-3227. ISSN 0003-4819. PMID 30884526. S2CID 83458685.

- Balk, Ethan; Adam, Gaelen P.; Kimmel, Hannah; Rofeberg, Valerie; Saeed, Iman; Jeppson, Peter; Trikalinos, Thomas (2018-08-08). "Nonsurgical Treatments for Urinary Incontinence in Women: A Systematic Review Update". doi:10.23970/ahrqepccer212. S2CID 80659370.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Choi H, Palmer MH, Park J (2007). "Meta-analysis of pelvic floor muscle training: randomized controlled trials in incontinent women". Nursing Research. 56 (4): 226–34. doi:10.1097/01.NNR.0000280610.93373.e1. PMID 17625461. S2CID 13508756.

- Wallace, Sheila A; Roe, Brenda; Williams, Kate; Palmer, Mary (26 January 2004). "Bladder training for urinary incontinence in adults". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD001308. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001308.pub2. PMC 7027684. PMID 14973967.

- Fader, Mandy; Cottenden, Alan M; Getliffe, Kathryn (8 October 2008). "Absorbent products for moderate-heavy urinary and/or faecal incontinence in women and men". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD007408. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007408. PMID 18843748.

- Lipp, Allyson; Shaw, Christine; Glavind, Karin (2014-12-17). "Mechanical devices for urinary incontinence in women". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD001756. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001756.pub6. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 7061494. PMID 25517397.

- Ford, AA; Rogerson, L; Cody, JD; Aluko, P; Ogah, JA (31 July 2017). "Mid-urethral sling operations for stress urinary incontinence in women". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (7): CD006375. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006375.pub4. PMC 6483329. PMID 28756647.

- Shaw JS. Old wine into new wineskins: an update for female stress urinary incontinence. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2019;31(6):494-500. doi:10.1097/GCO.0000000000000579.

- Heneghan CJ, Goldacre B, Onakpoya I,etal.Trials of transvaginal meshdevices for pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic database review of the USFDA approval process. BMJ Open 2017; 7:e017125.

- Shaw JS. Old wine into new wineskins: an update for female stress urinary incontinence. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2019;31(6):494-500. doi:10.1097/GCO.0000000000000579.

- Stenchever MA (2001). "Chapter 21. Physiology of micturition, diagnosis of voiding dysfunction and incontinence: surgical and nonsurgical treatment section of Urogynecology". Comprehensive Gynecology (4 ed.). pp. 607–639. ISBN 978-0-323-01402-1.

- Suarez, Oscar A.; McCammon, Kurt A. (June 2016). "The Artificial Urinary Sphincter in the Management of Incontinence". Urology. 92: 14–19. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2016.01.016. ISSN 1527-9995. PMID 26845050.

- Wang, Yang; Zhishun, Liu; Peng, Weina; Zhao, Jie; Liu, Baoyan (1 July 2013). "Acupuncture for stress urinary incontinence in adults". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD009408. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009408.pub2. PMID 23818069.