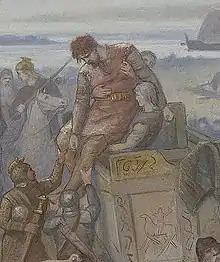

Styrbjörn the Strong

Styrbjörn the Strong (Old Norse: Styrbjǫrn Sterki [ˈstyrˌbjɔrn ˈsterke]; died about 985) according to late Norse sagas was a son of the Swedish king Olof, and a nephew of Olof's co-ruler and successor Eric the Victorious, who defeated and killed Styrbjörn at the Battle of Fyrisvellir.[1] As with many figures in the sagas, doubts have been cast on his existence,[2] but he is mentioned in a roughly contemporaneous skaldic poem about the battle. According to legend, his original name was Björn, and Styr-, which was added when he had grown up, was an epithet meaning that he was restless, controversially forceful and violent.[3]

Prose retellings

It is believed that there once was a full saga about Styrbjörn, but most of what is extant is found in the short Styrbjarnar þáttr Svíakappa. Parts of his story are also retold in Eyrbyggja saga, Saxo Grammaticus' Gesta Danorum (book 10), Knýtlinga saga and Hervarar saga. He is also mentioned in the Heimskringla (several times), and in Yngvars saga víðförla, where Ingvar the Far-Travelled is compared to his kinsman Styrbjörn. Oddr Snorrason also mentions him in Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar (around 1190), writing that Styrbjörn was defeated through magic. In modern days, he is also the hero of a novel called Styrbiorn the Strong by English author E. R. Eddison (1926),[4] and he is featured in The Long Ships, by Frans G Bengtsson.

Contemporaneous poetry

The extant poetry on Styrbjörn is found in Styrbjarnar þáttr Svíakappa, where the following lausavísa (about 985) mentions him:

Eigi vildu Jótar

reiða gjald til skeiða,

áðr Styrbjarnar stœði

Strandar dýr á landi.

Nús Danmarkar dróttinn

í drengja lið genginn;

landa vanr ok lýða

lifir ánauðigr auðar.

- The Jótar were not willing to pay tribute for ships before the beasts of Strǫnd <river> [SHIPS] of Styrbjǫrn stood by the coast. Now the lord of Denmark [DANISH KING = Haraldr] has joined the troop of warriors; he lives oppressed by fate, deprived of lands and people.[5]

The contemporary skald Þórvaldr Hjaltason also described the Battle of Fyrisvellir in the following pair of lausavísur, for which Eric rewarded him with two rings both worht a half mark, one for each stanza:

Fari* til Fýrisvallar,

folka tungls, hverrs hungrar,

vǫrðr, at virkis garði

vestr kveldriðu hesta.

Þar hefr hreggdrauga hǫggvit

— hóll*aust es þat — sólar

elfar skíðs fyr ulfa

Eirekr í dyn geira.

- Guardian of the sun of battles [SWORD > WARRIOR], let every one of the horses of the evening-rider [TROLL-WOMAN > WOLVES] who is hungry go west to Fýrisvǫllr, to the enclosure of the stronghold. There Eiríkr has cut down the storm-logs of the sun of the ski of the river [SHIP > SHIELD > BATTLE > WARRIORS] before wolves in the tumult of spears [BATTLE]; that is without exaggeration.[6]

Illr varð ǫlna fjalla

auðkveðjǫndum beðjar

til Svíþjóðar síðan

sveimr víkinga heiman.

Þat eitt lifir þeira,

— þeir hǫfðu lið fleira —

— gótt vas her at henda

Hundings — es rann undan.

- The vikings’ surge from their home to Sweden turned out afterwards [to be] disastrous for the wealth-demanders of the bed of fish of the mountains [SNAKES > GOLD > MEN]. Only that part of them survives, that ran away; they had the more numerous force; it was good to catch Hundingr’s army.[7]

Hundmargs ("of a myriad") in the second verse has also been read as Hundings, referring to a chief of the Jomsvikings named Hunding, but there is no other record of such a historical figure, so the argument that this disproves Styrbjörn's historical existence has been generally set aside in favour of the evidence of the other contemporary poem.[8]

Styrbjarnar þáttr Svíakappa

Styrbjarnar þáttr Svíakappa ('the tale of Styrbjörn the Swedish Champion'), preserved in the Flatey Book, is the source that contains the most material about Styrbjörn.

According to the tale, Styrbjörn, who was originally called Björn, was the son of Olof, a brother of King Eric, who died of poisoning when Björn was still a young boy. When he was 12 years old, he asked his uncle King Eric for his birthright, but was denied the co-rulership until he turned 16. One day he got into a fight with and killed a courtier, who had hit him on the nose with a drinking horn.

When he was 16, the Thing decided that he was not fit to be king, and instead appointed a man of low birth. His uncle Eric did not want him to stay at home, because of his violent nature and the complaints from the free farmers, so he gave Björn 60 well equipped longships, whereupon the frustrated boy took his sister Gyrid and left. Eric also called him "Styrbjörn", adding Styr- because of his nephew's unruly and quarrelsome nature.

He ravaged the shores of the Baltic Sea and when he was twenty, took the stronghold of Jomsborg from its founder Palnetoke and became the ruler of the Jomsvikings. After some time he allied himself with the Danish king Harald Bluetooth and had his sister Gyrid married to him. Styrbjörn married Harald's daughter Tyra Haraldsdotter whom he was given by Harald for conquering Jomsborg.

Harald gave him even more warriors and now Styrbjörn set about trying to take the throne of Sweden. He sailed with a huge force which included 200 Danish longships in addition to his own Jomsvikings. When they arrived at Föret (Old Norse Fyris) in Uppland, he burnt the ships in order to force his men to fight to the end. However, the Danish force changed its mind and returned to Denmark. Styrbjörn marched alone with his Jomsvikings to Gamla Uppsala. His uncle, however, was prepared and had sent for reinforcements from all directions.

During the first two days, the battle was even. The latter evening, Eric went to the statue of Odin at the Temple at Uppsala, where he made a sacrifice. He promised Odin that if he won the battle, he would belong to Odin and arrive at Valhalla ten years from then. The next day, Eric threw his spear over the enemy and said, "I sacrifice you all to Odin". Styrbjörn and his sworn men stayed and died.

Eyrbyggja saga

The Eyrbyggja saga has a short summary of Styrbjörn's career in connection with one of its protagonists:

But when Biorn came out over the sea, he went south to Denmark, and then south further to Jomsburg, and in those days was Palnatoki captain of the Jomsburg Vikings. Biorn entered into covenant with them, and was called a champion there. He was in Jomsburg when Styrbiorn the Strong won it, and he went to Sweden when they of Jomsburg gave aid to Styrbiorn, and was withal at the battle at Fyrisfield where Styrbiorn fell, and fled thence to the woods with the other Jomsburg Vikings. And while Palnatoki was alive was Biorn with him, and was deemed the best of men and the bravest in all deeds that try a man.[9]

Hervarar saga

The Hervarar saga gives an even shorter summary of Styrbjörn's story and his battle with his uncle Eric:

Olaf was the father of Styrbjörn the Strong. In their days King Harold the Fair-haired died. Styrbjörn fought against King Eric his father's brother at Fyrisvellir, and there Styrbjörn fell. Then Eric ruled Sweden till the day of his death.[10]

Knýtlinga saga

The Knýtlinga saga recounts that Styrbjörn was the son of the Swedish king Olaf. When Harald Bluetooth ruled Denmark, Styrbjörn was making war in the east (í hernaði í Austrveg) and then came to Denmark where he took Harald captive. Harald gave his daughter Tyra to Styrbjörn and joined him on his expedition to Sweden. On arrival, Styrbjörn set his own ships on fire, but when Harald saw that Styrbjörn no longer had any ships he sailed back out onto Lake Mälaren (Löginn) and returned to Denmark. Styrbjörn fought his uncle Eric on the Fyrisvellir and he fell together with most of his men. Some of his men fled and this the Swedes called the Fyriselta, the chase of the Fyris.

Gesta Danorum

The Danish chronicler Saxo Grammaticus tells a more pro-Danish version in Gesta Danorum (Book 10). According to him, Styrbjörn was the son of the Swedish king Björn. Styrbjörn had an uncle named Olaf, whose son Eric had taken the Swedish kingdom from Styrbjörn. Styrbjörn came to Harald Bluetooth, bringing his sister Gyrithe with him, and humbly asked Harald for help. Harald decided to befriend Styrbjörn and Harald offered his sister Gyrithe to be Stybjörn's wife. Harald then conquered the land of the Slavs and took the stronghold Julin (Jomsborg), which he gave to Styrbjörn to command with a strong force. Styrbjörn and his force (the Jomsvikings) dominated the seas, winning many victories, and they were more beneficial to Denmark than any force on land would have been. Among the warriors were Bue, Ulf, Karlsevne and Sigvald.

Styrbjörn wanted revenge and asked Harald for help to take the throne of Sweden. Harald wanted to help Styrbjörn and to this end he sailed to Halland, but was informed that the German emperor Otto had attacked Jutland, and Harald was more eager to defend his own country than to attack another one. When Harald had driven away the Germans, Styrbjörn had already rashly departed with his own force for Sweden, where he fell.

Alleged descendants

In the 18th century, Danish historian Jacob Langebek proposed that Styrbjörn and Tyra were the parents of Thorkel Sprakalegg, who was father of Ulf the Earl and of Gytha Thorkelsdóttir, wife of Godwin, Earl of Wessex, and thus grandfather of kings Sweyn II of Denmark and Harold Godwinson of England.[11][12] The earliest known source which says anything about the father of Thorkell Sprakalegg was the chronicle of John of Worcester, who says that 'Spraclingus' was son of 'Urso', (Latin for bear) which would be Bjorn. Both Saxo Grammaticus and Gesta Antecessorum Comitis Gualdevi derive Thorkel from the mating of a bear with a noblewoman, Saxo relating that they produced a son named for his father (i.e. named Bjorn), who was in turn father of 'Thrugillus, called Sprageleg', while the Gesta tells a similar story but turns the Urso, father of 'Spratlingus' (sic) in John of Worcester's pedigree into the actual bear involved.[13] Langebek suggested that Saxo's tale of a 'Wild' Björn, father of Thorkel, was an allegorical reference to Styrbjörn.[11] Otto Brenner, in his accounting of the descendants of Gorm the Old, rejects Thorkill as son of Styrbjörn and Thyra.[14]

Notes

- Maj Odelberg (1995). Styrbjörn Starke. ISBN 91-7192-984-3. Archived from the original on 2012-03-06.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Nationalencyklopedin short-form article Styrbjörn Starke, jomsvikingarnas hövding vars existens har betvivlats, "chief of the Jomsvikings whose existence has been doubted."

- C. Georg Starbäck in Berättelser ur Swenska Historien Första delen: Sagoåldern Norrköping 1860 p. 230-231

- Andrew Wawn, Philology and Fantasy before Tolkien, archived from the original on 2005-03-07

- Anonymous Lausavísur (Anon) at Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages. This verse is referred to in the longer version of "Styrbjörn Starke". Nationalencyklopedin..

- at Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages

- at Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages

- Sten Körner, "Slaget på Fyrisvallarna: Till Tolkningen av Torvald Hjaltasons Skaldeversar," Scandia 28,2 (1962) 391-98, (pdf; Swedish with English summary); the argument was made by Ove Moberg.

- The Story of the Ere-Dwellers, trans.William Morris and Eirikr Magnusson London: Quaritch, 1892, chapter 29 Archived 2011-07-19 at the Wayback Machine.

- Nora Kershaw Chadwick, Stories and Ballads of the Far Past: Translated from the Norse Icelandic and Faroese, Cambridge University Press, 1921, "The Saga of Hervör and Heithrek" Archived 2006-12-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Jacob Langebek (1774), Scriptores Rerum Danicarum Medii Ævi, vol. 3, pp. 281-282

- P. A. Munch (1853), Det Norske Folks Historie, vol. 1, no. 2, p. 101

- Timothy Bolton (2007), "Was the Family of Earl Siward and Earl Waltheof a Lost Line of the Ancestors of the Danish Royal Family", Nottingham Medieval Studies, 51:41-71

- Siegfried Otto Brenner (1964), "Nachkommen Gorms des Alten (König von Dänemark - 936 -): I. - XVI", pp. 1-3

References

- Henrikson, Alf: Stora mytologiska uppslagsboken.

- Jómsvíkíngasaga ok Knytlínga 1828 edition

- Slaget på Fyrisvallarna i ny tolkning (The Battle of Fýrisvellir in a New Interpretation), Thunberg, Carl L. (2012)

- S. Tunberg (1918). "Styrbjörn". Nordisk familjebok.

- Verner von Heidenstam (1908). "Hjälmdis rider till Erik Segersäll". Svenskarna och deras hövdingar. (with the tale of Styrbjörn)

- Cultural Paternity in the Flateyjarbók Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar by Elizabeth Ashman Rowe (this scholar has got Eric's agreement with Odin slightly wrong. Eric did not promise 10 years to Odin, he promised to belong to Odin after 10 years)