Sucellus

In Gallo-Roman religion, Sucellus or Sucellos (/suːˈkɛləs/) was a god shown carrying a large mallet (or hammer) and an olla (or barrel). Originally a Celtic god, his cult flourished not only among Gallo-Romans, but also to some extent among the neighbouring peoples of Raetia and Britain. He has been associated with agriculture and wine, particularly in the territory of the Aedui.[1]

Sculptures

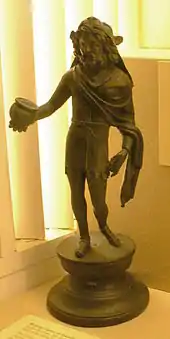

He is usually portrayed as a middle-aged bearded man wearing a wolf-skin, with a long-handled hammer, or perhaps a beer barrel suspended from a pole. His companion Nantosuelta is sometimes depicted alongside him. When together, they are accompanied by symbols associated with prosperity and domesticity.

In a well-known relief from Sarrebourg, near Metz, Nantosuelta, wearing a long gown, is standing to the left. In her left hand she holds a small house-shaped object with two circular holes and a peaked roof – perhaps a dovecote – on a long pole. Her right hand holds a patera which she is tipping onto a cylindrical altar. To the right Sucellus stands, bearded, in a tunic with a cloak over his right shoulder. He holds his mallet in his right hand and an olla in his left. Above the figures is a dedicatory inscription and below them in very low relief is a raven. This sculpture was dated by Reinach, from the form of the letters, to the end of the first century or start of the second century.[2]

Inscriptions

At least eleven inscriptions to Sucellus are known,[3] mostly from Gaul. One (RIB II, 3/2422.21) is from Eboracum (modern York) in Britain.

In an inscription from Augusta Rauricorum (modern Augst), Sucellus is identified with Silvanus:[4]

- In honor(em) /

- d(omus) d(ivinae) deo Su/

- cello Silv(ano) /

- Spart(us) l(ocus) d(atus) d(ecreto) d(ecurionum)

The syncretism of Sucellus with Silvanus can also be seen in artwork from Narbonensis.[5]

Roles and Duties

In Italy, Silvanus was said to protect forests and fields. He presided over the boundaries of properties, together with a host of local silvani, three for each property. These were the silvanus of the home, the silvanus of the fields, and the silvanus of the boundaries.[6] Silvanus also takes care of flocks, guaranteeing their fertility and protecting them from wolves, which is why he often wears the skin of a wolf.[7] When moving north into Gaul, Silvanus was syncretically merged with Sucellus to form the conflated Sucellus-Silvanus. It was Sucellus who carried the mallet and bowl. It has been suggested that the mallet was for construction and the erection of fence-posts (establishing boundaries), but this is far from certain.[8][9] Green claims that Sucellus may also relate to a chthonic deity, especially in maintain boundaries between the living and dead.[10]

Etymology

In Gaulish, the root cellos can be interpreted as 'striker', derived from Proto-Indo-European *-kel-do-s whence also come Latin per-cellere ('striker'), Greek klao ('to break') and Lithuanian kálti ('to hammer, to forge').[11] The prefix su- means 'good' or 'well' and is found in many Gaulish personal names.[12] Sucellus is therefore commonly translated as 'the good striker.'

An alternate etymology is offered by Celticist Blanca María Prósper, who posits a derivative of the Proto-Indo-European root *kel- ‘to protect’, i.e. *su-kel-mó(n) "having a good protection" or *su-kel-mṇ-, an agentive formation meaning "protecting well, providing good protection", with a thematic derivative built on the oblique stem, *su-kel-mn-o- (and subsequent simplification and assimilation of the sonorant cluster and a secondary full grade of the root). Prósper suggests the name would then be comparable to the Indic personal name Suśarman-, found in Hindu mythology.[13]

See also

- The Dagda, a similar figure from Irish mythology

References

- Miranda Green (2003). Symbol and Image in Celtic Religious Art. Routledge. p. 83.

- Reinach (1922), pp. 217–232.

- Jufer & Luginbühl (2001), p. 63.

- AE 1926, 00040

- Duval (1993), p. 78.

- Hyginus. "De limitibus constituendi, preface".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Virgil, Æneid VIII.600-1; Nonnus II.324; Cato the Elder, De re rusticâ 83; Tibullus, I.v.27.

- Smith, William. "A Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology. (1867)".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Deo Sucello Silvano".

- Aldhouse-Green, Miranda J. (2011). The gods of the Celts. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-6811-2. OCLC 797966528.

- Delamarre (2003), p. 113.

- Delamarre (2003), pp. 283–284.

- Prósper, Blanca María (2015). "Celtic and Non-Celtic Divinities from Ancient Hispania: Power, Daylight, Fertility, Water Spirits and What They Can Tell Us about Indo-European Morphology". The Journal of Indo-European Studies. 43 (1 & 2): 35–36.

Further reading

- Delamarre, Xavier (2003). Dictionnaire de la Langue Gauloise (2nd ed.). Paris: Éditions Errance. ISBN 2-87772-237-6.

- Deyts, Simone, ed. (1998). À la rencontre des Dieux gaulois, un défi à César. Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux. ISBN 2-7118-3851-X.

- Duval, Paul-Marie (1993) [1957]. Les dieux de la Gaule. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France / Éditions Payot.

- Heichelheim F. M., Housman J. E. "Sucellus and Nantosuelta in Mediaeval Celtic Mythology". In: L'antiquité classique, Tome 17, fasc. 1, 1948. Miscellanea Philologica Historica et archaelogia in honorem Hvberti Van De Weerd. pp. 305–316. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/antiq.1948.2845] www.persee.fr/doc/antiq_0770-2817_1948_num_17_1_2845

- Jufer, Nicole; Luginbühl, Thierry (2001). Répertoire des dieux gaulois. Paris: Éditions Errance. ISBN 2-87772-200-7.

- Reinach, Salomon (1922). Cultes, mythes et religions. Paris E. Leroux.