United States v. E. C. Knight Co.

United States v. E. C. Knight Co., 156 U.S. 1 (1895), also known as the "Sugar Trust Case," was a United States Supreme Court antitrust case that severely limited the federal government's power to pursue antitrust actions under the Sherman Antitrust Act. In Chief Justice Melville Fuller's majority opinion, the Court held that the US Congress could not regulate manufacturing and thus gave state governments the sole power to take legal action against manufacturing monopolies.[1] The case has never been overruled, but in Swift & Co. v. United States and subsequent cases, the Court has held that Congress can regulate manufacturing when it affects interstate commerce.

| United States v. E.C. Knight Co. | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued October 4, 1894 Decided January 21, 1895 | |

| Full case name | United States v. E.C. Knight Co. |

| Citations | 156 U.S. 1 (more) 15 S. Ct 249; 39 L. Ed. 325; 1895 U.S. LEXIS 2118 |

| Case history | |

| Prior | 60 F. 306 (C.C.E.D. Pa. 1894); affirmed, 60 F. 934 (3d Cir. 1894) |

| Holding | |

| Manufacturing is not considered an area that can be regulated by Congress pursuant to the commerce clause. | |

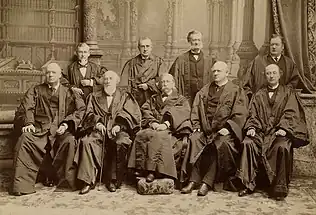

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Fuller, joined by Field, Gray, Brewer, Brown, Shiras, Jackson, White |

| Dissent | Harlan |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. Art. I, Sec 8. | |

The case

In 1892, the American Sugar Refining Company gained control of the E. C. Knight Company and several others, which resulted in a 98% monopoly of the American sugar refining industry. US President Grover Cleveland, in his second term of office (1893–1897), directed the national government to sue the Knight Company under the provisions of the Sherman Antitrust Act to prevent the acquisition. The question the court had to answer was, "could the Sherman Antitrust Act suppress a monopoly in the manufacture of a good, as well as its distribution?"

The decision

The court's 8–1 decision, handed down on January 21, 1895 and written by Chief Justice Melville Weston Fuller, went against the government. Justice John Marshall Harlan dissented.

The Court held "that the result of the transaction was the creation of a monopoly in the manufacture of a necessary of life"[1] but ruled that it "could not be suppressed under the provisions of the act."[1]

The Court ruled that manufacturing, in this case, refining, was a local activity, not subject to congressional regulation of interstate commerce. Fuller wrote:

That which belongs to commerce is within the jurisdiction of the United States, but that which does not belong to commerce is within the jurisdiction of the police power of the State. . . . Doubtless the power to control the manufacture of a given thing involves in a certain sense the control of its disposition, but . . . affects it only incidentally and indirectly.

The decision required any action against manufacturing monopolies to be taken by individual states. The ruling prevailed until the end of the 1930s, when the Court took a different position on the federal government's power to regulate the economy.

In his dissent, Harlan argued "the doctrine of the autonomy of the states cannot properly be invoked to justify a denial of power in the national government to meet such an emergency." He continued to argue the Constitution gives Congress "authority to enact all laws necessary and proper" to regulate commerce and cited McCulloch v. Maryland. .[1]

Later developments

Although the decision was never expressly overturned, the Court later retreated from its position in a series of cases such as Swift and Company v. United States, which have defined various steps of the manufacturing process as part of commerce. Eventually, E.C. Knight came to be a precedent narrowed to its precise facts, with no other force.

See also

- Antitrust

- Commerce Clause

- Sugar companies of the United States

- Sugar industry of the United States

External links

Works related to United States v. E. C. Knight Company at Wikisource

Works related to United States v. E. C. Knight Company at Wikisource- Text of United States v. E. C. Knight Co., 156 U.S. 1 (1895) is available from: Cornell Justia Library of Congress