Hippodrome of Constantinople

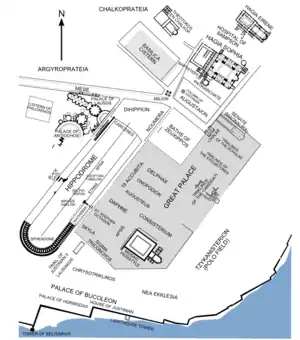

The Hippodrome of Constantinople (Greek: Ἱππόδρομος τῆς Κωνσταντινουπόλεως, romanized: Hippódromos tēs Kōnstantinoupóleōs; Latin: Circus Maximus Constantinopolitanus; Turkish: Hipodrom), was a circus that was the sporting and social centre of Constantinople, capital of the Byzantine Empire. Today it is a square in Istanbul, Turkey, known as Sultanahmet Square (Turkish: Sultanahmet Meydanı).

| Hippodrome | |

|---|---|

| Sultanahmet Square (Sultanahmet Meydanı) | |

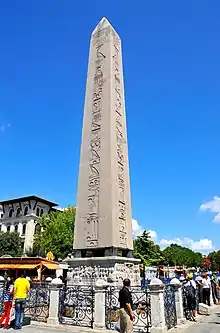

.jpg.webp) Obelisk of Theodosius in Sultanahmet Square today | |

| |

| Location | Istanbul, Turkey |

| Coordinates | 41°00′23″N 28°58′33″E |

The word hippodrome comes from the Greek hippos (ἵππος), horse, and dromos (δρόμος), path or way. For this reason, it is sometimes also called Atmeydanı ("Horse Square") in Turkish. Horse racing and chariot racing were popular pastimes in the ancient world and hippodromes were common features of Greek cities in the Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine eras.

History and use

Construction

Although the Hippodrome is usually associated with Constantinople's days of glory as an imperial capital, it actually predates that era. The first Hippodrome was built when the city was called Byzantium, and was a provincial town of moderate importance. In AD 203 the Emperor Septimius Severus rebuilt the city and expanded its walls, endowing it with a hippodrome, an arena for chariot races and other entertainment.

In AD 324, the Emperor Constantine the Great decided to refound Byzantium after his victory at the nearby Battle of Chrysopolis; he renamed it Nova Roma (New Rome). This name failed to impress and the city soon became known as Constantinople, the City of Constantine. Constantine greatly enlarged the city, and one of his major undertakings was the renovation of the Hippodrome. It is estimated that the Hippodrome of Constantine was about 450 m (1,476 ft) long and 130 m (427 ft) wide. The carceres (starting gates) stood at the northern end; and the sphendone (curved tribune of the U-shaped structure, the lower part of which still survives) stood at the southern end.[1] The spina (the middle barrier of the racecourse) was adorned with various monuments, including the monolithic obelisk, the erection of which is depicted in relief carvings on its base.

The stands were capable of holding 100,000 spectators. The race-track at the Hippodrome was U-shaped, and the Kathisma (emperor's lodge) was located at the eastern end of the track. The Kathisma could be accessed directly from the Great Palace through a passage which only the emperor or other members of the imperial family could use.

Decoration

The hippodrome was filled with statues of gods, emperors, animals, and heroes, among them some famous works, such as a 4th-century BC Heracles by Lysippos, Romulus and Remus with the she-wolf Lupa, and the 5th-century BC Serpent Column.[4] The carceres had four statues of horses in gilded copper on top, now called the Horses of Saint Mark. The horses' exact Greek or Roman ancestry has never been determined. They were looted during the Fourth Crusade in 1204 and installed on the façade of St Mark's Basilica in Venice. The track was lined with other bronze statues of famous horses and chariot drivers, none of which survive. In his book De Ceremoniis (book II,15, 589), the Emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus described the decorations in the hippodrome at the occasion of the visit of Saracen or Arab visitors, mentioning the purple hangings and rare tapestries.[5] According to Hesychius of Miletus, there was once a statue of Hecate at the site.[6]

Functions

Throughout the Byzantine period, the Hippodrome was the centre of the city's social life. Huge amounts were bet on chariot races, and initially four teams took part in these races, each one financially sponsored and supported by a different political party (Deme) within the Byzantine Senate: The Blues (Venetoi), the Greens (Prasinoi), the Reds (Rousioi) and the Whites (Leukoi). The Reds (Rousioi) and the Whites (Leukoi) gradually weakened and were absorbed by the other two major factions (the Blues and Greens).

A total of up to eight chariots (two chariots per team), powered by four horses each, competed on the racing track of the Hippodrome. These races were not simple sporting events, but also provided some of the rare occasions in which the emperor and the common citizens could come together in a single venue. Political discussions were often made at the Hippodrome, which could be directly accessed by the emperor through a passage that connected the Kathisma with the Great Palace of Constantinople.

The rivalry between the Blues and Greens often became mingled with political or religious rivalries, and sometimes riots, which amounted to civil wars that broke out in the city between them. The most severe of these was the Nika riots of 532, in which an estimated 30,000 people were killed[7] and many important buildings were destroyed, such as the nearby second Hagia Sophia, the Byzantine cathedral. The current (third) Hagia Sophia was built by Justinian I following the Nika riots.

Decline

Constantinople never recovered from its sack during the Fourth Crusade and even though the Byzantine Empire survived until 1453, by that time, the Hippodrome had fallen into ruin, pillaged by the Venetians who likely took the four horses now in San Marco from a monument there.[8] The Ottomans, whose Sultan Mehmed II captured the city in 1453 and made it the capital of the Ottoman Empire, were not interested in chariot racing and the Hippodrome was gradually forgotten, although the site was never actually built over. The hippodrome was used as a source of building stone, however.[9]

Hippodrome monuments

Serpent Column

.jpg.webp)

To raise the image of his new capital, Constantine and his successors, especially Theodosius the Great, brought works of art from all over the empire to adorn it. The monuments were set up in the middle of the Hippodrome, the spina. Among these was the sacrificial tripod of Plataea, now known as the Serpent Column, cast to celebrate the victory of the Greeks over the Persians during the Persian Wars in the 5th century BC. Constantine ordered the Tripod to be moved from the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, and set in middle of the Hippodrome. The top was adorned with a golden bowl supported by three serpent heads, although it appears that this was never brought to Constantinople. The serpent heads and top third of the column were destroyed in 1700.[10] Parts of the heads were recovered and are displayed at the Istanbul Archaeology Museum. All that remains of the Delphi Tripod today is the base, known as the "Serpent Column".

Obelisk of Thutmose III

Another emperor to adorn the Hippodrome was Theodosius the Great, who in 390 brought an obelisk from Egypt and erected it inside the racing track. Carved from pink granite, it was originally erected at the Temple of Karnak in Luxor during the reign of Thutmose III in about 1490 BC. Theodosius had the obelisk cut into three pieces and brought to Constantinople. The top section survives, and it stands today where Theodosius placed it, on a marble pedestal. The granite obelisk has survived nearly 3,500 years in good condition.

Walled Obelisk

In the 10th century the Emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus built another obelisk at the other end of the Hippodrome. It was originally covered with gilded bronze plaques, but they were sacked by Latin troops in the Fourth Crusade.[1] The stone core of this monument also survives, known as the Walled Obelisk.

Statues of Porphyrius

Seven statues were erected on the Spina of the Hippodrome in honour of Porphyrius the Charioteer, a legendary charioteer of the early 6th century who in his time raced for the two parties which were called "Greens" and "Blues". None of these statues have survived. The bases of two of them have survived and are displayed in the Istanbul Archaeological Museum.

Contemporary description

The area is officially called Sultanahmet Square. It is maintained by the Turkish government. The course of the old racetrack has been indicated with paving, although the actual track is some 2 m (6.6 ft) below the present surface. The surviving monuments of the Spina, the two obelisks and the Serpentine Column, now sit excavated in pits in a landscaped garden.

The German Fountain ("The Kaiser Wilhelm Fountain"), an octagonal domed fountain in neo-Byzantine style, which was constructed by the German government in 1900 to mark the visit of the German Emperor Wilhelm II to Istanbul in 1898, is located at the northern entrance to the Hippodrome area, right in front of the Blue Mosque.

In 1855, Charles Thomas Newton, the English archaeologist who excavated Halicarnassus and Cnidus, excavated the one surviving jaw of a snake from the Serpent Column. The Hippodrome was excavated by the Director of the Istanbul Archeological Museums, archaeologist Rüstem Duyuran in 1950 and 1951.[11][12] A portion of the substructures of the sphendone (the curved end) became more visible in the 1980s with the clearing of houses in the area. In 1993 an area in front of the nearby Sultanahmet Mosque (the Blue Mosque) was bulldozed in order to install a public building, uncovering several rows of seats and some columns from the Hippodrome. Investigation did not continue further, but the seats and columns were removed and can now be seen in Istanbul's museums. It is possible that much more of the Hippodrome's remains still lie beneath the parkland of Sultanahmet.

The Hippodrome was depicted on the reverse of the Turkish 500 lira banknotes of 1953–1976.[13]

Image gallery

The four bronze horses that stood atop the Hippodrome boxes, today at St. Mark's Basilica in Venice

The four bronze horses that stood atop the Hippodrome boxes, today at St. Mark's Basilica in Venice Base of the statues of Porphyrios, kept in the Istanbul Museum

Base of the statues of Porphyrios, kept in the Istanbul Museum

The Hippodrome in 2005, with the Walled Obelisk in the foreground and the Obelisk of Thutmose III on the right

The Hippodrome in 2005, with the Walled Obelisk in the foreground and the Obelisk of Thutmose III on the right The base of the Obelisk of Thutmose III showing Emperor Theodosius as he offers a laurel wreath to the victor from the Kathisma at the Hippodrome

The base of the Obelisk of Thutmose III showing Emperor Theodosius as he offers a laurel wreath to the victor from the Kathisma at the Hippodrome Procession of the guilds in front of the Sultan in the Hippodrome, Ottoman miniature from the Surname-i Vehbi (1582)

Procession of the guilds in front of the Sultan in the Hippodrome, Ottoman miniature from the Surname-i Vehbi (1582) The Grand Vizier Crossing the Atmeydanı by Jean Baptiste Vanmour shows the Hippodrome and the Blue Mosque in the early 17th century

The Grand Vizier Crossing the Atmeydanı by Jean Baptiste Vanmour shows the Hippodrome and the Blue Mosque in the early 17th century.jpg.webp) Watercolour of the Hippodrome's spina and Hagia Sophia from a manuscript in the library of Trinity College, Cambridge

Watercolour of the Hippodrome's spina and Hagia Sophia from a manuscript in the library of Trinity College, Cambridge Engraving by William Watts after Luigi Mayer of the Atmeydanı and the Blue Mosque

Engraving by William Watts after Luigi Mayer of the Atmeydanı and the Blue Mosque Sultanahmet Square from the sky, the surviving lower walls of the Sphendone of the Hippodrome is visible.

Sultanahmet Square from the sky, the surviving lower walls of the Sphendone of the Hippodrome is visible. Depiction of an Arab captive demonstrating his skills to the emperor in the Hippodrome. Miniature from the 12th century Madrid Skylitzes.

Depiction of an Arab captive demonstrating his skills to the emperor in the Hippodrome. Miniature from the 12th century Madrid Skylitzes.

References

- "Hippodrome - Istanbul, Turkey Attractions". www.lonelyplanet.com.

- E. Jeffreys et al. (eds.), The Oxford handbook of Byzantine studies (2008), 207; R. Krautheimer, Three Christian capitals: topography and politics (1983), 136 n. 14.

- Dash, Mike. "Blue versus Green: Rocking the Byzantine Empire".

- Sarah Guberti Bassett (1991). "The Antiquities in the Hippodrome of Constantinople". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Vol. 45. 45: 87–96. doi:10.2307/1291694. JSTOR 1291694.

- Rodolphe Guilland (1948). "The Hippodrome at Byzantium". Speculum. Speculum, Vol. 23, No. 4. 23 (4): 676–682. doi:10.2307/2850448. JSTOR 2850448. S2CID 162820978.

- Patria of Constantinople

- This is the number given by Procopius, Wars (Internet Medieval Sourcebook.)

- "Museo San Marco Venezia - St Mark's Museum Venice Italy". www.venetoinside.com.

- "Hippodrome - architecture". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Thomas F. Madden, "The Serpent Column of Delphi in Constantinople: Placement, Purposes, and Mutilations," Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies 16 (1992): 111-45.

- Erdem, Yasemin Tümer. "Atatürk Dönemi Arkeoloji Çalışmalarından Biri: Sultanahmet Kazısı," ATATÜRK ARAŞTIRMA MERKEZİ DERGİSİ, Sayı 62, Cilt: XXI, July 2005. İstanbul’da yapılan başlıca arkeolojik araştırmalar = Principal Archeological Researches... İstanbul / Rüstem Duyuran. 1957.

- "Retrieved on 11 March 2010". Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey Archived 2009-06-03 at WebCite. Banknote Museum: 5. Emission Group - Five Hundred Turkish Lira - I. Series Archived 2009-02-04 at the Wayback Machine, II. Series Archived 2009-02-04 at the Wayback Machine, III. Series Archived 2009-02-04 at the Wayback Machine & IV. Series Archived 2009-02-04 at the Wayback Machine. – Retrieved on 20 April 2009.

- "An illustration of Byzantine era Constantinople, with the Hippodrome of Constantinople appearing prominently at the center of the image". vividmaps.com. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- "Aerial view of the Hippodrome of Constantinople, with the surviving lower walls of the Sphendone (curved grandstand) in the foreground". Retrieved 31 January 2021.

Further reading

- Weitzmann, Kurt, ed., Age of spirituality: late antique and early Christian art, third to seventh century, no. 101, 1979, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, ISBN 9780870991790; full text available online from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries

- Pitarakis, Brigitte & Isin, Ekrem, ed., Hippodrom/Atmeydani: istanbul’un tarih sahnesi - Hippodrome/Atmeydani: A stage for Istanbul’s history, 2 volumes, 2010, Pera Müsezi, Istanbul.

- Langdale, Allan. The Hippodrome of Istanbul / Constantinople: an illustrated handbook of its history (2019).

External links

- Byzantium 1200 | Hippodrome with images of original appearance

- Over 150 pictures of the monuments

- Istanbul Official Museums Website

- Photos with explanations

.jpg.webp)