Sultan Djabir

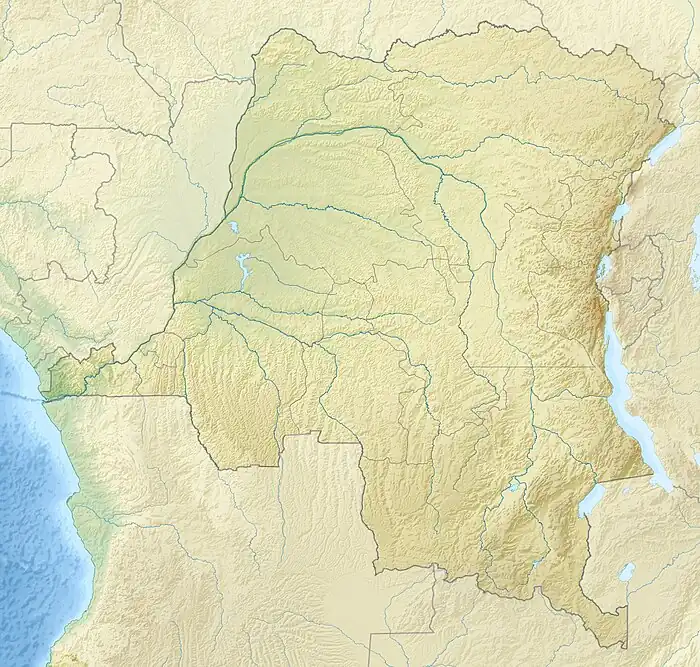

Sultan Djabir (or Bokoyo, born c. 1855 – 11 January 1918) was ruler of a region on the Uele River in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. He engaged in the ivory and slave trade with Muslims from the north and with Belgians from the south. Eventually he was forced to flee to the Sudan when he refused to pay tribute to the Congo Free State.

Djabir | |

|---|---|

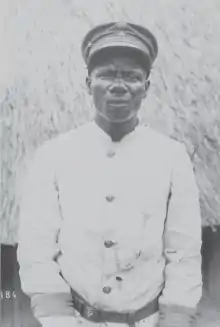

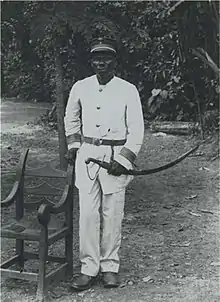

Sultan Djabir in 1894 wearing the uniform of the Force Publique | |

| Born | Bokoyo c. 1850 |

| Died | 11 January 1918 |

| Nationality | Abandia |

| Occupation | Sultan |

| Known for | Slave and ivory trade |

Early years

Bokoyo was a paramount chief of the Bandia people, son of Dwaro and grandson of Hiro, born around 1855. He first settled near the Dume River, a tributary of the Mbomou River.[1] De Bauw says that when he was 14 years old he wanted to travel. An Arab caravan let him follow them north to Khartoum, where he stayed for three months.[2] According to de la Kethulle, he was a sincere Muslim who fasted and prayed during Ramadan. He also adopted Arabic dress.[3]

Around 1875, Bokoyo had to flee his father's residence and took refuge with Swa, son of Gaia, son of Gatanga, son of Ino, who kept him in detention for fear of his intrigues.[4] Bokoyo escaped and settled in the territory of Gezere, a Nubian who represented the Sudanese slave trader Al-Zubayr Rahma Mansur. He took the Muslim name of Djabir[lower-alpha 1], and travelled with Gezere to Khartoum.[1] He returned from Khartoum with the Arab Kabasi, then guided the Arab Alikobbo to the Bili River[lower-alpha 2] basin and towards the lower Uelé River.[4]

In 1884 the agents of the Egyptian government withdrew to Bahr el Ghazal to support Frank Lupton, who was cut off by the Mahdists. Djabir followed Alikobbo part of the way, then took his people, arms and ammunition and installed himself between the Angoli river and the territory of Ngia, his brother. Abdallah, a lieutenant of Alikobbo, remained at Bomu. Djabir attacked and defeated him on the Dume River. Taking Adballah's arms, Djabir moved south and settled on the Zagiri and Mamboya, tributaries that enter the Uelé River from the north. Sultan Rafai returned from Bahr el Ghazal where he had been fighting the Mahdists and settled at the Mago, downstream from Djabir. He did not trust Djabir, and imprisoned him for two years from 1886 to 1888. Djabir managed to escape, and after some maneuvering between the two sultans and their Arab allies Rafai moved to the north while Djabir contacted the Europeans at Basoko.[4]

European contact (1889–90)

Stanley Pool

Jérôme Becker met Sultan Djabir at Basoko in December 1889, and in January 1890 reached Djabir's sultanate.[7] Later in 1890 an expedition led by Léon Roget with Jules Alexandre Milz and Joseph Duvivier established the Ibembo station on the Itimbiri River and the Ekwangatana post.[8] On 25 May 1890 they crossed the Likati and on 27 May 1890 reached the Uele River opposite Sultan Djabar's village of Djabir (now called Bondo[lower-alpha 3]). Sultan Djabir signed a treaty with Milz and a post was established on the site of the former Egyptian zeriba of Deleb.[8]

Milz began construction of the station while Roget, guided by Sultan Djabir, tried unsuccessfully to join Alphonse van Gèle in Yakoma. Roget had gone north as far as Mbili and Gangu, having heard that the country downstream was too dangerous. On 9 June 1890 he returned to Djabir.[10] Roget left Djabir in July to return to Basoko, the Pool and Boma, leaving Milz in command with instructions to attempt the liaison with Yakoma.[11] In July–August 1890 Milz and his assistant Mahutte and Sultan Djabir led 100 fusiliers and 400 lancers in an attempt to push through the non-submissive people along the right bank, but were forced to return to Djabir after nine days.[11] Milz and van Gèle finally made contact on 3 December 1890, confirming that the Uelé was the upper portion of the Ubangi.[12]

Djabir became an officer in the Force Publique and was paid an annual salary.[13] Clément-François Vande Vliet described Djabir as he was in October 1891,

The Sultan was a man in his forties, quite stout and above average height. He was hairless; his face was round and marked on the forehead by a vertical line of dotted tattoos. He wore a fine white linen shirt, the breastplate of which he had put on from behind, wide Arab breeches, yellow leather moccasins, and a straw hat covered with a white headdress. The little finger of his left hand was adorned with a silver signet ring. He was polite and presented himself fairly well. He had Dahia as a trusted man, who had previously traveled through Sudan with him and had known Gessi, Junker, Emin and Lupton. "[4]

Slave and ivory trade

In December 1891 Sultan Djabir sold the Congo Free State 156 adult slaves and 65 children. Due to harsh treatment by the Belgians, few of them survived. Djabir sold hundreds of slaves to the state at a rate of 10 men for one musket, raiding the neighboring villages to obtain men to serve in the Force Publique.[14] He and other sultans in the region traded with Belgian concessionaries such as the Société des Sultanats, selling ivory and slaves in return for guns and ammunition.[13] The sultans also sold slaves and ivory to Muslims from the Wadaï and other places to the north, receiving goods such as guns, salt, cattle and cloth in exchange.[15] The local chiefs would bring ivory and slaves to the town of Djabir, selling them inside the sultan's court, which was off-limits to Europeans.[16]

Last years

Marcus Dorman visited Djabir in 1904. He wrote,

The view of the town from the distance is very pretty indeed. In the centre is an old fort with four towers now partly demolished and on each side the houses of the officials stretching along the river bank... Djabir is a disappointing place. Although very imposing from a distance it is being rebuilt at present and at close quarters it becomes obvious that some of the old houses are in a very bad state of repair...

The Sultan of Djabir sent his brother, a young gentleman who has been educated and speaks French, to present a small ivory war-horn and to demand several times its value in cloth. Afterwards he sold us some other articles but, although he received full value for them he repented of his bargain next day and demanded them back again. Of course we let him take them. The Sultan himself seems to be equally difficult to deal with and although the State has given him the rank of Captain in the Force Publique and tried to humour him in every way he is not a good subject. His village has the usual characteristics with some signs of Arab civilisation.[17]

In 1905 the Congo Free State attacked Djabir, who had to flee to French territory to the north.[18] Although the Free State had known about Djabir's illicit trading, the Belgians tolerated it until he refused to pay tribute.[19] He settled in the Sudan near Deim Zubeir. He died there on 11 January 1918.[1]

Notes

- "Djabir", "Gabir" or "Jabir" is an Arabic name meaning "comforter".[5]

- The Bili River flows from east to west between the Mbomou River and the Uelé River. The three rivers converge near Yakoma to form the Ubangi River.[6]

- At the time, towns and villages were given the names of their chiefs. Djabir, named after the Sultan Djabir, was later called Bakango and today is called Bondo.[9]

Citations

- Bradshaw & Fandos-Rius 2016, p. 223.

- Luffin 2004, p. 151.

- Luffin 2004, p. 150.

- Lotar & Coosemans 1948, col.329-331.

- Campbell 1996.

- Relation: Bili (9566525).

- Luffin 2004, p. 149.

- Coosemans 1946.

- Kjerland & Bertelsen 2014, p. 353.

- Lotar 1937, p. 78.

- Lotar 1937, p. 80.

- Lotar 1937, p. 81.

- Bas De Roo 2014, p. 127.

- Bas De Roo 2014, p. 122.

- Bas De Roo 2014, p. 128.

- Bas De Roo 2014, pp. 128–129.

- Dorman 1905, Chapter VIII.

- Bas De Roo 2014, p. 134.

- Bas De Roo 2014, p. 137.

Sources

- Bas De Roo (2014), "Customs and Contraband in the Congolese M'Bomu Region" (PDF), Journal of Belgian History, XLIV (4), retrieved 2021-10-14

- Bradshaw, Richard; Fandos-Rius, Juan (27 May 2016), Historical Dictionary of the Central African Republic, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 9780810879928, retrieved 2021-10-14

- Campbell, Mike (1996), "Jabir", Behind the Name, retrieved 2021-10-18

- Coosemans, M. (20 May 1946), "MILZ (Jules-Alexandre)", Biographie Belge d'Outre-Mer (in French), vol. I, Académie Royale des Sciences d'Outre-Mer, pp. 697–701, retrieved 2020-08-30

- Dorman, Marcus Roberts Phipps (1905), A Journal of a Tour in the Congo Free State, Brussels: J. Lebègue and Co., retrieved 2021-10-14

- Kjerland, Kirsten Alsaker; Bertelsen, Bjørn Enge (1 November 2014), Navigating Colonial Orders: Norwegian Entrepreneurship in Africa and Oceania, Berghahn Books, ISBN 978-1-78238-540-0, retrieved 30 August 2020

- Lotar, R. P. L. (1937), La Grande Chronique de l'Ubangi (PDF), Institut Royal Colonial Beige, retrieved 2020-08-31

- Lotar, P.-L.; Coosemans, M. (1948), Biographie Belge d'Outre-Mer (in French) (PDF) (in French), vol. I, Académie Royale des Sciences d'Outre-Mer, retrieved 2021-10-14

- Luffin, Xavier (2004), "The Use Of Arabic As A Written Language In Central Africa The Case Of The Uele Basin (Northern Congo) In The Late Nineteenth Century" (PDF), Sudanic Africa, 15: 145–177, retrieved 2020-08-27

- "Relation: Bili (9566525)", OpenStreetMap, retrieved 2021-10-18