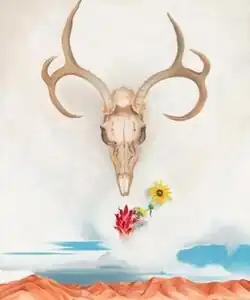

Summer Days (Georgia O'Keeffe)

Summer Days is a 1936 oil painting by the American 20th-century artist Georgia O'Keeffe. It depicts a buck deer skull with large antlers juxtaposed with a vibrant assortment of wildflowers hovering below. The skull and flowers are suspended over a mountainous desert landscape occupying the lower part of the composition. Summer Days is among several landscape paintings featuring animal skulls and inspired by New Mexico desert O'Keeffe completed between 1934 and 1936.

| Summer Days | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Georgia O'Keeffe |

| Year | 1936 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Movement | Modernism |

| Dimensions | 76.5 cm × 91.8 cm (30.1 in × 36.1 in) |

| Location | Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City |

| Accession | 94.171 |

The juxtaposition of skull and landscape imagery in Summer Days has prompted various interpretations. While some art historians and critics see them as commonplace desert elements, others emphasize the painting's transcendental or mystical potential. O'Keeffe, who never assigned any specific symbolic meaning to her use of skeletal motifs, associated the inclusion of bones in her artwork with the raw, alive essence of the desert, and later defined Summer Days as simply a "portrayal of summertime".

The work was first exhibited at Alfred Stieglitz's New York gallery space called An American Place in 1937 and remained with O'Keeffe for numerous years, later featuring on the cover of her monographic book published in 1976 by Viking Press. The Museum of Fine Arts, Santa Fe attempted to acquire the painting in 1980, but financial disagreements within the museum led to its return to O'Keeffe. Summer Days was eventually purchased by the American fashion designer Calvin Klein in 1983, who later donated it to the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1994. It has been described as one of O'Keeffe's most recognized paintings.[1][2]

Historical context

Georgia O'Keeffe was an American modernist painter and draftswoman whose career spanned seven decades and whose work remained largely independent of major art movements.[3] As art historian Lisa Messinger notes, much of O'Keeffe's art was predicated on finding "essential, abstract forms in nature" usually expressed through meticulous paintings of landscapes, flowers, and bones, which were often drawn from and related to places and environments in which she lived.[3] During the 1920s, O'Keeffe's work was actively promoted by her husband, Alfred Stieglitz, who was a prominent New York photographer and gallerist. Through Stieglitz, O'Keeffe met numerous prominent contemporary artists, including Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, Charles Demuth, and Edward J. Steichen.[3]

By 1929, her marriage had deteriorated after she found out about Stieglitz's extramarital affair with a fellow artist Dorothy Norman. That year, in part motivated by her desire to spend time away from Stieglitz, she traveled to Santa Fe for the first time.[4] She would subsequently visit New Mexico on near annual basis from 1929 onward, often staying there several months at a time, returning to New York each winter to exhibit her work at Stieglitz's gallery.[3] The skull motifs, inspired by animal skulls and bones collected in the New Mexico desert, began appearing in O'Keeffe's work in 1931.[3] By the early 1930s, the news of Stieglitz's adultery had taken a significant emotional toll on O'Keeffe who suffered a nervous breakdown in 1932 and was hospitalized for psychoneurosis in New York in 1933.[5] Since the mid-1930s, she began to spend increasingly more time around Santa Fe, particularly at Ghost Ranch, resulting in a new series of works, in which the artist combined and juxtaposed various landscapes motifs of the New Mexico desert and skeletal imagery.[3]

Analysis

Description

_by_Georgia_O'Keefe.png.webp)

Summer Days, which O'Keeffe completed in 1936, is divided into what art historian Sarah Whitaker Peters describes as "two uneven spaces". The top three-fourths of the painting consist of a large and naturalistic rendition of a large buck deer skull with its antlers extending toward the top edge of the canvas. Six wildflowers painted in red and yellow are seen floating against "an indeterminate mist" and a "metaphysical space".[6]: 193 The bottom fourth of the composition is occupied by a mountainous landscape. According to Peters, the red hills shown in the composition are evocative of Mesozoic rock formations similar to the landscape environment of the Ghost Ranch.[6]: 193 Peters further suggests that the depicted flowers include a Castilleja (known as "Indian paintbrush"), two asters, and a Helianthella quinquenervis (known as "little sunflower").[6]: 195

Reception

Summer Days was first shown in 1937 at An American Place in New York, an exhibition venue established by Stieglitz in 1929. Stieglitz is said to have disliked the painting's title, a sentiment he expressed openly to a journalist from The New York Times following the exhibition's opening, and hoped that exhibition viewers would "supply" a title of their own.[6][7] The painting has been described as representing a "distinctive iconography of the American Southwest" and was among several landscape compositions featuring animal skulls O'Keeffe completed between 1934 and 1936, including Rams Head with Hollyhock (1935) and Deer's Head with Pedernal (1936).[8]: 288 [6]: 188 O'Keeffe's use of the skull motifs, which she introduced to her work in 1931 after bringing home bones collected from a New Mexico desert, was a subject of critical debate during the late 1930s.[6]: 190

Some art critics interpreted the inclusion of animal skulls as mundane elements of a desert landscape while others speculated about their transcendent or mystical potential.[6]: 190 At the same time, O'Keeffe maintained that she did not intend for these motifs to carry any specific symbolism.[9] Speaking to her interest in incorporating depictions of skulls and bones into her paintings, O'Keeffe wrote in 1939, two years after Summer Days was first exhibited, that "The bones seem to cut sharply to the center of something that is keenly alive in the desert even tho’ it is vast and empty and untouchable—and knows no kindness with all its beauty".[9] She would later describe Summer Days simply as a "picture of summertime".[10]

Influences and scholarship

Art historian Britta Benke argues that due to "its meditative contemplation of individual objects", Summer Days is closer to a still life composition than to a landscape painting.[11] Author Marjorie P. Balge-Crozier suggests that there is an art historical precedent to O'Keefe's combination of still life and landscape imagery seen in Summer Days. In particular, she points to the work of the French 18th-century painters Alexandre-François Desportes and Jean-Baptiste Oudry in which the artists combined "foreground displays of food, dead game, and dogs with background views of landscape or architecture".[12]: 64

In her analysis of O'Keeffe's 1936 composition, Balge-Crozier also discusses the relevance of the American late 19th-century "trophy paintings" of artists like William Michael Harnett and his followers. Specifically, she references Harnett's 1885 composition titled After the Hunt which includes trompe-l'œil representations of "dead game" against weapons, a horn, and other objects commonly associated with American hunting traditions.[12]: 64 At the same time, Balge-Crozier notes that trompe-l'oeil—a tradition of painting in which the artist depicts objects with the highest degree of verisimilitude so as to deceive the viewer into thinking the painted space is real—was not well suited to evoke the emotional response O'Keeffe "hoped for in the dialogue between nature and art".[12]: 65

Discussing possible 20th-century inspirations, art historian Sasha Nicholas notes that Summer Days demonstrates O'Keeffe's "awareness of the incongruous aesthetic juxtapositions" present in the work of contemporary Surrealist artists in the United States and Europe.[8]: 288 The influence of Surrealism in Summer Days is also noted by scholar Henry W. Peacock who finds a parallel between the visual components of O'Keeffe's 1936 painting and the "illusionistic and diminutive positive form floating in deep space" typical of some Surrealist paintings.[13] Predating Surrealism, Whitaker points to O'Keeffe's long-standing interest in 19th-century Symbolist art which had to do with "suggestion, allusion, and equivalence", indicating that the artist was sympathetic to the Symbolist belief in the "curative" properties of form and color.[6]: 194

When commenting on O'Keeffe's use of flowers in the composition, a very popular subject matter in her work, Peters speculates that the largest red flower, which she identifies as an Indian paintbrush, might be a "cryptic abstract portrait" of Stieglitz. She notes that creating non-representational portraits of other artists was encouraged and practiced in Stieglitz's New York circle, to which O'Keeffe belonged.[6]: 195 Scholar and political scientist Timothy W. Luke argues that the artist's juxtaposition of skeletal imagery from the desert and flowers against the landscape of the Cerro Pedernal mesa or Abiquiu hills in New Mexico, evident in Summer Days and other compositions from that period, "directly tap into the mass culture's utopian vision of the West" already cultivated in numerous American literary works and movies made between the 1920s and 1950s.[14]

History of ownership

Following its first display at An American Place in 1937, the painting remained with O'Keeffe for several decades. It was later featured on the cover of Georgia O'Keeffe, an illustrated 1976 monograph of the artist's career published by Viking Press.[15] In 1980, curator Ellen Bradbury and architect Edward Larrabee Barnes negotiated the acquisition of Summer Days for the Museum of Fine Arts, Santa Fe for US$350,000.[1] After being temporarily displayed in one of the museum's main galleries, financial disputes within the institution ultimately led to the acquisition being cancelled and the painting was soon returned to the artist. In 1983, the work was purchased by the American fashion designer Calvin Klein for US$1 million. In 1994, Klein donated Summer Days to the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.[15] It has since been a part of the Whitney's permanent collection.[16]

Gallery

William Michael Harnett, After the Hunt, Oil on canvas, 1885 (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco)

William Michael Harnett, After the Hunt, Oil on canvas, 1885 (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco) Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O'Keeffe, Hands and Horse Skull, photograph, 1931 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O'Keeffe, Hands and Horse Skull, photograph, 1931 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

References

- Drohojowska-Philp, Hunter (2004). Full Bloom: The Art and Life of Georgia O'Keeffe. New York, New York: W.W. Norton. p. 536. ISBN 978-0-393-32741-0.

- Abrams, Dennis (2009). Georgia O'Keeffe. New York, New York: Chelsea House. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-1-60413-336-3.

- Messinger, Lisa (October 2004). "Georgia O'Keeffe (1887–1986)". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2023-05-29.

- Drohojowska-Philp, Hunter (2004). Full Bloom: The Art and Life of Georgia O'Keeffe. New York, NY: W. W. Norton. pp. 294–296. ISBN 978-0-393-32741-0.

- Udall, Sharyn Rohlfsen (2000). Carr, O'Keeffe, Kahlo. Places of Their Own. New Haven and New York: Yale University Press. pp. 317–319. ISBN 0-300-07958-3.

- Norris, Kathleen, Wagner M., Anne, Peters, Sarah Whitaker (1999). "Georgia O'Keeffe. Summer Days. 1936". In Venn, Beth (ed.). Frames of Reference: Looking at American art, 1900-1950. Works from the Whitney Museum of American Art. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. pp. 186–195. ISBN 978-0-520-21888-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Jewell, Edward Alden (1937-02-06). "Georgia O'Keeffe Shows New Work". The New York Times. p. 7. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-06-27.

The levitation theme is still fruitful, giving us, now, a canvas called in the catalogue "Summer Days". Mr. Stieglitz says he doesn't in the least like that title. In fact he admitted yesterday: "I hate it". Mr. Stieglitz hopes that each visitor to the gallery will supply a title of his own.

- Nicholas, Sasha (2015). "Georgia O'Keeffe". In Miller, Dana (ed.). Whitney Museum of American Art: Handbook of the Collection. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art and Yale University Press. pp. 286–288. ISBN 978-0-300-21183-2.

- Tomkins, Calvin (1974-02-25). "Georgia O'Keeffe's Vision". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved 2023-05-27.

- Lisle, Laurie (1997). Portrait of an Artist. A Biography of Georgia O'Keeffe. New York: Washington Square Press. p. 294. ISBN 978-0671016661.

- Benke, Britta (2000). Georgia O'Keeffe, 1887-1986: Flowers in the Desert. Köln: Taschen. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-3-8228-5861-5.

- Balge-Crozier, Marjorie P. (1999). "Still Life Redefined". In Turner, Elizabeth Hutton (ed.). Georgia O'Keeffe: The Poetry of Things. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. pp. 63–65. ISBN 978-0-300-07935-7.

- Peacock, Henry W. (1995). Art as Expression. Washington, D.C: Whalesback Books. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-929590-14-1.

- Luke, Timothy W. (1992). "Georgia O'Keeffe". Shows of Force. Power, Politics, and Ideology in Art Exhibitions. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-8223-1123-2.

- Reily, Nancy Hopkins (2009). Georgia O'Keeffe, A Private Friendship, Part II. Santa Fe, New Mexico: Sunstone Press. p. 450. ISBN 978-0-86534-452-5.

- "Georgia O'Keeffe, Summer Days, 1936". Collection, Whitney Museum. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art. Retrieved 2023-05-27.