Super Audio CD

Super Audio CD (SACD) is an optical disc format for audio storage introduced in 1999. It was developed jointly by Sony and Philips Electronics and intended to be the successor to the compact disc (CD) format.

| |

| Media type | Optical disc |

|---|---|

| Encoding | Digital (DSD) |

| Capacity | 4.38 GiB / 4.7 GB (Single Layer and Hybrid) 7.92 GiB / 8.5 GB (Dual Layer) |

| Read mechanism | 650 nm laser (780 nm for the CD layer of a Hybrid disc) |

| Standard | Scarlet Book |

| Developed by | Sony & Philips |

| Usage | Audio storage |

| Extended from | Compact Disc Digital Audio |

| Released | 1999 |

| Optical discs |

|---|

The SACD format allows multiple audio channels (i.e. surround sound or multichannel sound). It also provides a higher bit rate and longer playing time than a conventional CD.

An SACD is designed to be played on an SACD player. A hybrid SACD contains a Compact Disc Digital Audio (CDDA) layer and can also be played on a standard CD player.

History

The Super Audio CD format was introduced in 1999,[1] and is defined by the Scarlet Book standard document. Philips and Crest Digital partnered in May 2002 to develop and install the first SACD hybrid disc production line in the United States, with a production capacity of up to three million discs per year.[2] SACD did not achieve the level of growth that compact discs enjoyed in the 1980s,[3] and was not accepted by the mainstream market.[4][5][6]

By 2007, SACD had failed to make a significant impact in the marketplace; consumers were increasingly downloading low-resolution music files over the internet rather than buying music on physical disc formats.[1] A small and niche market for SACD has remained, serving the audiophile community.[7]

Content

By October 2009, record companies had published more than 6,000 SACD releases, slightly more than half of which were classical music. Jazz and popular music albums, mainly remastered previous releases, were the next two genres most represented.

Many popular artists have released some or all of their back catalog on SACD. Pink Floyd's album The Dark Side of the Moon (1973) sold over 800,000 copies by June 2004 in its SACD Surround Sound edition.[8] The Who's rock opera Tommy (1969), and Roxy Music's Avalon (1982), were released on SACD to take advantage of the format's multi-channel capability. All three albums were remixed in 5.1 surround, and released as hybrid SACDs with a stereo mix on the standard CD layer.

Some popular artists have released new recordings on SACD. Sales figures for Sting's Sacred Love (2003) album reached number one on SACD sales charts in four European countries in June 2004.[8]

Between 2007 and 2008, the rock band Genesis re-released all of their studio albums across three SACD box sets. Each album in these sets contains both new stereo and 5.1 mixes. The original stereo mixes were not included. The US & Canada versions do not use SACD but CD instead.

By August 2009 443 labels[9] had released one or more SACDs. Instead of depending on major label support, some orchestras and artists have released SACDs on their own. For instance, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra started the Chicago Resound label to provide full and burgeoning support for high-resolution SACD hybrid discs, and the London Symphony Orchestra established their own LSO Live label.

Many SACD discs that were released from 2000-2005 are now out of print and available only on the used market.[7][10] By 2009, the major record companies were no longer regularly releasing discs in the format, with new releases confined to the smaller labels.[11]

Technology

| Characteristic | CD layer (optional) | SACD layer |

|---|---|---|

| Disc capacity | 700 MB[12] | 4.7 GB[13] |

| Audio encoding | 16-bit pulse-code modulation | 1-bit Direct Stream Digital |

| Sampling frequency | 44.1 kHz | 2,822.4 kHz (2.8224 MHz) |

| Audio channels | 2 (stereo) | Up to 6 (discrete surround) |

| Playback time if stereo | 80 minutes[14] | 110 minutes without DST compression[13] |

SACD discs have identical physical dimensions as standard compact discs. The areal density of the disc is the same as a DVD. There are three types of disc:[13]

- Hybrid: Hybrid SACDs have a 4.7 GB SACD layer (the HD layer), as well as a CD (Red Book) audio layer readable by most conventional compact disc players.[15]

- Single-layer: A disc with one 4.7 GB SACD layer.

- Dual-layer: A disc with two SACD layers, totaling 8.5 GB, and no CD layer. Dual-layer SACDs can store nearly twice as much data as a single-layer SACD. Like most dual-layer DVDs, the data spiral for the first layer is encoded from the inside out, and the second layer is encoded starting from the point where the first layer ends and ending at the innermost part of the disc. Unlike hybrid discs, both single- and dual-layer SACDs are incompatible with conventional CD players and cannot be played on them.

A stereo SACD recording has an uncompressed rate of 5.6 Mbit/s, four times the rate for Red Book CD stereo audio.[13]

Commercial releases commonly include both surround sound (five full-range plus LFE multi-channel) and stereo (dual-channel) mixes on the SACD layer. Some reissues retain the mixes of earlier multi-channel formats (examples include the 1973 quadraphonic mix of Mike Oldfield's Tubular Bells and the 1957 three-channel stereo recording by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra of Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition, reissued on SACD in 2001 and 2004 respectively).

Disc reading

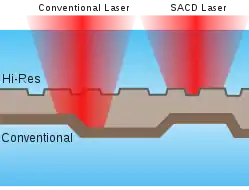

Objective lenses in conventional CD players have a longer working distance, or focal length, than lenses designed for SACD players. In SACD-capable DVD, Blu-ray and Ultra HD Blu-ray players, the red DVD laser is used for reading SACDs. This means that when a hybrid SACD is placed into a conventional CD player, the infrared laser beam passes through the SACD layer and is reflected by the CD layer at the standard 1.2 mm distance, and the SACD layer is out of focus. When the same disc is placed into an SACD player, the red laser is reflected by the SACD layer (at 0.6 mm distance) before it can reach the CD layer. Conversely, if a conventional CD is placed into an SACD player, the laser will read the disc as a CD since there is no SACD layer.[13][16]

Direct Stream Digital

SACD audio is stored in Direct Stream Digital (DSD) format using pulse-density modulation (PDM) where audio amplitude is determined by the varying proportion of 1s and 0s. This contrasts with compact disc and conventional computer audio systems using pulse-code modulation (PCM) where audio amplitude is determined by numbers encoded in the bit stream. Both modulations require neighboring samples to reconstruct the original waveform; the more neighboring samples, the lower the frequency that can be encoded.

DSD is 1-bit, has a sampling rate of 2.8224 MHz, and makes use of noise shaping quantization techniques in order to push 1-bit quantization noise up to inaudible ultrasonic frequencies. This gives the format a greater dynamic range and wider frequency response than the CD. The SACD format is capable of delivering a dynamic range of 120 dB from 20 Hz to 20 kHz and an extended frequency response up to 100 kHz, although most available players list an upper limit of 70–90 kHz,[17] and practical limits reduce this to 50 kHz.[13] Because of the nature of sigma-delta converters, DSD and PCM cannot be directly compared. DSD's frequency response can be as high as 100 kHz, but frequencies that high compete with high levels of ultrasonic quantization noise.[18] With appropriate low-pass filtering, a frequency response of 20 kHz can be achieved along with a dynamic range of nearly 120 dB, which is about the same dynamic range as PCM audio with a resolution of 20 bits.

Direct Stream Transfer

To reduce the space and bandwidth requirements of DSD, a lossless data compression method called Direct Stream Transfer (DST) is used. DST compression is compulsory for multi-channel regions and optional for stereo regions. It typically compresses by a factor of between two and three, allowing a disc to contain 80 minutes of both 2-channel and 5.1-channel sound.[19]

Direct Stream Transfer compression was standardized as an amendment to the MPEG-4 Audio standard, ISO/IEC 14496-3:2001/Amd 6:2005 (Lossless coding of oversampled audio), in 2005.[20][21] It contains the DSD and DST definitions as described in the Super Audio CD Specification.[22] The MPEG-4 DST provides lossless coding of oversampled audio signals. Target applications of DST are archiving and storage of 1-bit oversampled audio signals and SA-CD.[23][24][25]

A reference implementation of MPEG-4 DST was published as ISO/IEC 14496-5:2001/Amd.10:2007 in 2007.[26][27]

Copy protection

SACD has several copy protection features at the physical level, which made the digital content of SACD discs difficult to copy until the jailbreak of the PlayStation 3. The content may be copyable without SACD quality by resorting to the analog hole, or ripping the conventional 700 MB layer on hybrid discs. Copy protection schemes include physical pit modulation and 80-bit encryption of the audio data, with a key encoded on a special area of the disc that is only readable by a licensed SACD device. The HD layer of an SACD disc cannot be played back on computer CD/DVD drives, and SACDs can only be manufactured at the disc replication facilities in Shizuoka and Salzburg.[28][29] Nonetheless, a PlayStation 3 with an SACD drive and appropriate firmware can use specialized software to extract a DSD copy of the HD stream.

Sound quality

Sound quality parameters achievable by the Red Book CD-DA and SACD formats compared with the limits of human hearing are as follows:

- CD

- Dynamic range: 90 dB;[30] 120 dB (with shaped dither); [31] frequency range: 20 Hz—20 kHz[12]

- SACD

- Dynamic range: 105 dB;[12] frequency range: 20 Hz— 50 kHz[13]

- Human hearing

- Dynamic range: 120 dB;[32] frequency range: 20 Hz—20 kHz (young person); 20 Hz—8-15 kHz (middle-aged adult)[32]

In September 2007, the Audio Engineering Society published the results of a year-long trial, in which a range of subjects including professional recording engineers were asked to discern the difference between high-resolution audio sources (including SACD and DVD-Audio) and a compact disc audio (44.1 kHz/16 bit) conversion of the same source material under double-blind test conditions. Out of 554 trials, there were 276 correct answers, a 49.8% success rate corresponding almost exactly to the 50% that would have been expected by chance guessing alone.[33] When the level of the signal was elevated by 14 dB or more, the test subjects were able to detect the higher noise floor of the CD-quality loop easily. The authors commented:[34]

Now, it is very difficult to use negative results to prove the inaudibility of any given phenomenon or process. There is always the remote possibility that a different system or more finely attuned pair of ears would reveal a difference. But we have gathered enough data, using sufficiently varied and capable systems and listeners, to state that the burden of proof has now shifted. Further claims that careful 16/44.1 encoding audibly degrades high resolution signals must be supported by properly controlled double-blind tests.

Following criticism that the original published results of the study were not sufficiently detailed, the AES published a list of the audio equipment and recordings used during the tests.[35] Since the Meyer-Moran study in 2007,[36] approximately 80 studies have been published on high-resolution audio, about half of which included blind tests. Joshua Reiss performed a meta-analysis on 20 of the published tests that included sufficient experimental detail and data. In a paper published in the July 2016 issue of the AES Journal,[37] Reiss says that, although the individual tests had mixed results, and that the effect was "small and difficult to detect," the overall result was that trained listeners could distinguish between hi-resolution recordings and their CD equivalents under blind conditions: "Overall, there was a small but statistically significant ability to discriminate between standard quality audio (44.1 or 48 kHz, 16 bit) and high-resolution audio (beyond standard quality). When subjects were trained, the ability to discriminate was far more significant." Hiroshi Nittono pointed out that the results in Reiss's paper showed that the ability to distinguish high-resolution audio from CD-quality audio was "only slightly better than chance."[38]

Contradictory results have been found when comparing DSD and high-resolution PCM formats. Double-blind listening tests in 2004 between DSD and 24-bit, 176.4 kHz PCM recordings reported that among test subjects no significant differences could be heard.[39] DSD advocates and equipment manufacturers continue to assert an improvement in sound quality above PCM 24-bit 176.4 kHz.[40] A 2003 study found that despite both formats' extended frequency responses, people could not distinguish audio with information above 21 kHz from audio without such high-frequency content.[41] In a 2014 study, however, Marui et al. found that under double-blind conditions, listeners were able to distinguish between PCM (192 kHz/24 bits) and DSD (2.8 MHz) or DSD (5.6MHz) recording formats, preferring the qualitative features of DSD, but could not discriminate between the two DSD formats.[42]

Playback hardware

The Sony SCD-1 player was introduced concurrently with the SACD format in 1999, at a price of approximately US$5,000.[43] It weighed over 26 kilograms (57 lb) and played two-channel SACDs and Red Book CDs only. Electronics manufacturers, including Onkyo,[44] Denon,[45] Marantz,[46][47] Pioneer[48][49] and Yamaha[50] offer or offered SACD players. Sony has made in-car SACD players.[51]

In order to playback SACD content digitally without any conversion, some players are able to offer an output carrying encrypted streams of DSD, either via IEEE 1394[52] or more commonly, HDMI.[53]

SACD players are not permitted to offer an output carrying an unencrypted stream of DSD.[54]

The first two generations of Sony's PlayStation 3 game console were capable of reading SACD discs. Starting with the third generation (introduced October 2007), SACD playback was removed.[55] All PlayStation 3 models, however, will play DSD Disc format. The PlayStation 3 was capable of converting multi-channel DSD to lossy 1.5 Mbit/s DTS for playback over S/PDIF using the 2.00 system software. The subsequent revision removed the feature.[56]

Several brands have introduced (mostly high-end) Blu-ray Disc and Ultra HD Blu-ray players that can play SACD discs.[57]

Unofficial playback of SACD disc images on a PC is possible through freeware audio player foobar2000 for Windows using an open source plug-in extension called SACDDecoder. macOS music software Audirvana also supports playback of SACD disc images.

See also

References

- Jack Schofield (2 August 2007). "No taste for high-quality audio". The Guardian. Retrieved May 29, 2009.

- "Crest National and Philips Partner to Bring SACD Hybrid Disc Manufacturing to the USA". Newscenter.philips.com. 2002-05-30. Retrieved 2011-12-31.

- Mark Fleischmann. Are DVD-Audio and SACD DOA? April 2, 2004. Retrieved on January 16, 2010

- C|Net News, March 26, 2009, Betamax to Blu-ray: Sony format winners, losers by Steve Guttenberg. Retrieved on May 29, 2009

- Stereofile eNewsletter, January 10, 2006. Io Saturnalia! by Wes Phillips. Retrieved on May 28, 2009

- Audio Video Revolution, October 19, 2006. The Symbolism Of Losing Tower Records. Jerry Del Colliano. Retrieved on May 28, 2009

- "The 10 Best Audiophile SACDs Ever — Many Are Out Of Print". Audiophilereview.com. 27 November 2010. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- High Fidelity Review. Universal Music Artists Hit SACD Gold and Silver in Europe. Retrieved on May 18, 2009

- "SA-CD.net - Super Audio CD - FAQ". sa-cd.net.

- Sinclair, Paul (January 30, 2013). "Top 10: SACDs you can afford to buy". Retrieved 2013-03-11.

- Guttenberg, Steve (July 16, 2009). "Are SACD and DVD-Audio dead yet?". CNET. Retrieved 2013-03-11.

- Middleton, Chris; Zuk, Allen (2003). The Complete Guide to Digital Audio: A Comprehensive Introduction to Digital Sound and Music-Making. Cengage Learning. p. 54. ISBN 978-1592001026.

- Extremetech.com, Leslie Shapiro, July 2, 2001. Surround Sound: The High-End: SACD and DVD-Audio. Retrieved on May 20, 2009

- Clifford, Martin (1987). "The Complete Compact Disc Player." Prentice Hall. p. 57. ISBN 0-13-159294-7.

- PC Magazine Encyclopedia Definition of Hybrid SACD Retrieved June 16, 2009

- How A Hybrid Super Audio Compact Disc (SACD) Works. Retrieved June 16, 2009

- [http://tech.juaneda.com/en/articles/dsd.pdf Reefman, Derk; Nuijten, Peter. "Why Direct Stream Digital is the best choice as a digital audio format." (PDF) Audio Engineering Society Convention Paper 5396, May 2001.

- Ambisonic.net. Richard Elen, August 2001. Battle of the Discs. Retrieved on May 20, 2009

- Direct Stream Digital Technology. Retrieved June 3, 2009

- ISO/IEC (2006-03-14). "ISO/IEC 14496-3:2001/Amd 6:2005 – Lossless coding of oversampled audio". ISO. Retrieved 2009-10-09.

- ISO/IEC (2007-08-06). "ISO/IEC 14496-4:2004/Amd 15:2007 – Lossless coding of oversampled audio". ISO. Retrieved 2009-10-09.

- ISO/IEC JTC1/SC29/WG11/N6674 (July 2004), ISO/IEC 14496-3:2001/FPDAM6 (Lossless coding of oversampled audio). (DOC), retrieved 2009-10-09

- ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 29/WG 11 N7465 (July 2005). "Description Lossless coding of oversampled audio". chiariglione.org. Retrieved 2009-10-09.

- ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 29/WG 11 N7465 (July 2005). "Description Lossless coding of oversampled audio". Archived from the original on 2007-02-03. Retrieved 2009-12-28.

- ISO/IEC (2009-09-01), ISO/IEC 14496-3:2009 – Information technology – Coding of audio-visual objects – Part 3: Audio (PDF), IEC, retrieved 2009-10-07

- ISO/IEC (2007), ISO/IEC 14496-5:2001/Amd.10:2007 – Information technology – Coding of audio-visual objects – Part 5: Reference software – Amendment 10: SSC, DST, ALS and SLS reference software (ZIP), ISO, retrieved 2009-10-07

- ISO/IEC (2007-03-01), ISO/IEC 14496-5:2001/Amd.10:2007 – SSC, DST, ALS and SLS reference software, ISO, retrieved 2009-10-09

- "Sony Starts Hybrid Super Audio CD Production Facilities in Europe". SA-CD.net. 2003-01-22. Retrieved 2007-07-12.

- "Details of DVD-Audio and SACD". DVDdemystified.com. Retrieved 2007-07-12.

- Fries, Bruce; Marty Fries (2005). Digital Audio Essentials. O'Reilly Media. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-596-00856-7.

- "24/192 Music Downloads ...and why they make no sense". Xiph.org. 25 March 2012. Archived from the original on 26 April 2020.

- Rossing, Thomas (2007). Springer Handbook of Acoustics. Springer. pp. 747, 748. ISBN 978-0387304465.

- Galo, Gary (2008). "Is SACD doomed?" (PDF). Audioxpress.com. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- E. Brad Meyer & David R. Moran (September 2007). "Audibility of a CD-Standard A/D/A Loop Inserted into High-Resolution Audio Playback" (PDF). J. Audio Eng. Soc. Audio Engineering Society. 55 (9): 775–779 – via drewdaniels.com.

- Paul D. Lehrman: The Emperor's New Sampling Rate Mix online, April 2008.

- "Audibility of a CD-Standard A/D/A Loop Inserted into High-Resolution Audio Playback" (PDF). J. Audio Eng. Soc. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- Reiss, Joshua D. (27 June 2016). "A Meta-Analysis of High Resolution Audio Perceptual Evaluation". Journal of the Audio Engineering Society. J. Audio Eng. Soc. 64 (6): 364–379. doi:10.17743/jaes.2016.0015.

- Hiroshi Nittono (10 December 2020). "High-frequency sound components of high-resolution audio are not detected in auditory sensory memory". Scientific Reports. Nature. 10 (1): 21740. Bibcode:2020NatSR..1021740N. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-78889-9. PMC 7730382. PMID 33303915.

- Blech, Dominikp; Yang, Min-Chi (May 2004). "DVD-Audio versus SACD: Perceptual Discrimination of Digital Audio Coding Formats" (PDF). Convention Paper. Audio Engineering Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-06-18.

- "The 1-Bit Advantage – Future Proof Recording" (PDF). Korg. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-05-18.

- Toshiyuki Nishiguchi, Kimio Hamasaki, Masakazu Iwaki, and Akio Ando, Perceptual Discrimination between Musical Sounds with and without Very High Frequency Components Published by NHK Laboratories in 2004

- Marui, A., Kamekawa, T., Endo, K., & Sato, E. (2014, April). Subjective evaluation of high resolution recordings in PCM and DSD audio formats. In Audio Engineering Society Convention 136. Audio Engineering Society.

- "The Sony SCD-1 SACD Player". @udiophilia. Retrieved 2006-05-18.

- C-S5VL. Retrieved March 21, 2012

- DCD-SA1. Retrieved June 3, 2009

- Marantz's list of Hi-Fi Components. Retrieved June 3, 2009

- Marantz's "Reference series". Retrieved June 3, 2009

- PD-D6-J. Retrieved June 3, 2009

- PD-D9-J. Retrieved June 3, 2009

- Yamaha's web page. Retrieved June 3, 2009

- "Sony Announces Three Super Audio CD Car Stereo Players". High Fidelity Review. Archived from the original on 2007-03-02. Retrieved 2007-01-18.

- "Sony SCD-XA9000ES Operating Instructions" (PDF). Sony Electronics Inc. p. 32.

i.LINK section, Format (output)

- Harley, Robert (11 December 2008). "New Information on Oppo Blu-ray Player". The Absolute Sound.

- SACD Playback Requirements and Content Protection. Retrieved June 18, 2009

- "Why did Sony take SA-CD out of PS3 again?". PS3 SACD FAQ. Retrieved 2009-01-04.

- "Firmware v2.01". PS3SACD.com. November 22, 2007. Retrieved August 11, 2010.

- "Super Audio CD-compatible Blu-ray Disc players". Retrieved 2009-10-21.

Bibliography

- Janssen, E.; Reefman, D. "Super-audio CD: an introduction". Signal Processing Magazine, IEEE Volume 20, Issue 4, July 2003, pp. 83–90.

External links

- Super Audio Compact Disc: A Technical Proposal, Sony (archived PDF)

- SA-CD.net Reviews of SACD releases and a discussion forum.