Surjective function

In mathematics, a surjective function (also known as surjection, or onto function /ˈɒn.tuː/) is a function f such that every element y can be mapped from some element x such that f(x) = y. In other words, every element of the function's codomain is the image of at least one element of its domain.[1][2] It is not required that x be unique; the function f may map one or more elements of X to the same element of Y.

| Function |

|---|

| x ↦ f (x) |

| History of the function concept |

| Examples of domains and codomains |

| Classes/properties |

| Constructions |

| Generalizations |

The term surjective and the related terms injective and bijective were introduced by Nicolas Bourbaki,[3][4] a group of mainly French 20th-century mathematicians who, under this pseudonym, wrote a series of books presenting an exposition of modern advanced mathematics, beginning in 1935. The French word sur means over or above, and relates to the fact that the image of the domain of a surjective function completely covers the function's codomain.

Any function induces a surjection by restricting its codomain to the image of its domain. Every surjective function has a right inverse assuming the axiom of choice, and every function with a right inverse is necessarily a surjection. The composition of surjective functions is always surjective. Any function can be decomposed into a surjection and an injection.

Definition

A surjective function is a function whose image is equal to its codomain. Equivalently, a function with domain and codomain is surjective if for every in there exists at least one in with .[1] Surjections are sometimes denoted by a two-headed rightwards arrow (U+21A0 ↠ RIGHTWARDS TWO HEADED ARROW),[5] as in .

Symbolically,

- If , then is said to be surjective if

Examples

- For any set X, the identity function idX on X is surjective.

- The function f : Z → {0, 1} defined by f(n) = n mod 2 (that is, even integers are mapped to 0 and odd integers to 1) is surjective.

- The function f : R → R defined by f(x) = 2x + 1 is surjective (and even bijective), because for every real number y, we have an x such that f(x) = y: such an appropriate x is (y − 1)/2.

- The function f : R → R defined by f(x) = x3 − 3x is surjective, because the pre-image of any real number y is the solution set of the cubic polynomial equation x3 − 3x − y = 0, and every cubic polynomial with real coefficients has at least one real root. However, this function is not injective (and hence not bijective), since, for example, the pre-image of y = 2 is {x = −1, x = 2}. (In fact, the pre-image of this function for every y, −2 ≤ y ≤ 2 has more than one element.)

- The function g : R → R defined by g(x) = x2 is not surjective, since there is no real number x such that x2 = −1. However, the function g : R → R≥0 defined by g(x) = x2 (with the restricted codomain) is surjective, since for every y in the nonnegative real codomain Y, there is at least one x in the real domain X such that x2 = y.

- The natural logarithm function ln : (0, +∞) → R is a surjective and even bijective (mapping from the set of positive real numbers to the set of all real numbers). Its inverse, the exponential function, if defined with the set of real numbers as the domain and the codomain, is not surjective (as its range is the set of positive real numbers).

- The matrix exponential is not surjective when seen as a map from the space of all n×n matrices to itself. It is, however, usually defined as a map from the space of all n×n matrices to the general linear group of degree n (that is, the group of all n×n invertible matrices). Under this definition, the matrix exponential is surjective for complex matrices, although still not surjective for real matrices.

- The projection from a cartesian product A × B to one of its factors is surjective, unless the other factor is empty.

- In a 3D video game, vectors are projected onto a 2D flat screen by means of a surjective function.

Properties

A function is bijective if and only if it is both surjective and injective.

If (as is often done) a function is identified with its graph, then surjectivity is not a property of the function itself, but rather a property of the mapping.[7] This is, the function together with its codomain. Unlike injectivity, surjectivity cannot be read off of the graph of the function alone.

Surjections as right invertible functions

The function g : Y → X is said to be a right inverse of the function f : X → Y if f(g(y)) = y for every y in Y (g can be undone by f). In other words, g is a right inverse of f if the composition f o g of g and f in that order is the identity function on the domain Y of g. The function g need not be a complete inverse of f because the composition in the other order, g o f, may not be the identity function on the domain X of f. In other words, f can undo or "reverse" g, but cannot necessarily be reversed by it.

Every function with a right inverse is necessarily a surjection. The proposition that every surjective function has a right inverse is equivalent to the axiom of choice.

If f : X → Y is surjective and B is a subset of Y, then f(f −1(B)) = B. Thus, B can be recovered from its preimage f −1(B).

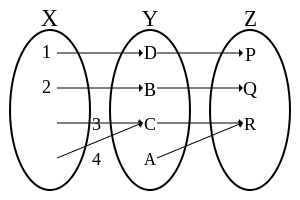

For example, in the first illustration above, there is some function g such that g(C) = 4. There is also some function f such that f(4) = C. It doesn't matter that g(C) can also equal 3; it only matters that f "reverses" g.

Surjections as epimorphisms

A function f : X → Y is surjective if and only if it is right-cancellative:[8] given any functions g,h : Y → Z, whenever g o f = h o f, then g = h. This property is formulated in terms of functions and their composition and can be generalized to the more general notion of the morphisms of a category and their composition. Right-cancellative morphisms are called epimorphisms. Specifically, surjective functions are precisely the epimorphisms in the category of sets. The prefix epi is derived from the Greek preposition ἐπί meaning over, above, on.

Any morphism with a right inverse is an epimorphism, but the converse is not true in general. A right inverse g of a morphism f is called a section of f. A morphism with a right inverse is called a split epimorphism.

Surjections as binary relations

Any function with domain X and codomain Y can be seen as a left-total and right-unique binary relation between X and Y by identifying it with its function graph. A surjective function with domain X and codomain Y is then a binary relation between X and Y that is right-unique and both left-total and right-total.

Cardinality of the domain of a surjection

The cardinality of the domain of a surjective function is greater than or equal to the cardinality of its codomain: If f : X → Y is a surjective function, then X has at least as many elements as Y, in the sense of cardinal numbers. (The proof appeals to the axiom of choice to show that a function g : Y → X satisfying f(g(y)) = y for all y in Y exists. g is easily seen to be injective, thus the formal definition of |Y| ≤ |X| is satisfied.)

Specifically, if both X and Y are finite with the same number of elements, then f : X → Y is surjective if and only if f is injective.

Given two sets X and Y, the notation X ≤* Y is used to say that either X is empty or that there is a surjection from Y onto X. Using the axiom of choice one can show that X ≤* Y and Y ≤* X together imply that |Y| = |X|, a variant of the Schröder–Bernstein theorem.

Composition and decomposition

The composition of surjective functions is always surjective: If f and g are both surjective, and the codomain of g is equal to the domain of f, then f o g is surjective. Conversely, if f o g is surjective, then f is surjective (but g, the function applied first, need not be). These properties generalize from surjections in the category of sets to any epimorphisms in any category.

Any function can be decomposed into a surjection and an injection: For any function h : X → Z there exist a surjection f : X → Y and an injection g : Y → Z such that h = g o f. To see this, define Y to be the set of preimages h−1(z) where z is in h(X). These preimages are disjoint and partition X. Then f carries each x to the element of Y which contains it, and g carries each element of Y to the point in Z to which h sends its points. Then f is surjective since it is a projection map, and g is injective by definition.

Induced surjection and induced bijection

Any function induces a surjection by restricting its codomain to its range. Any surjective function induces a bijection defined on a quotient of its domain by collapsing all arguments mapping to a given fixed image. More precisely, every surjection f : A → B can be factored as a projection followed by a bijection as follows. Let A/~ be the equivalence classes of A under the following equivalence relation: x ~ y if and only if f(x) = f(y). Equivalently, A/~ is the set of all preimages under f. Let P(~) : A → A/~ be the projection map which sends each x in A to its equivalence class [x]~, and let fP : A/~ → B be the well-defined function given by fP([x]~) = f(x). Then f = fP o P(~).

The set of surjections

Given fixed A and B, one can form the set of surjections A ↠ B. The cardinality of this set is one of the twelve aspects of Rota's Twelvefold way, and is given by , where denotes a Stirling number of the second kind.

Gallery

A non-injective surjective function (surjection, not a bijection)

A non-injective surjective function (surjection, not a bijection) An injective surjective function (bijection)

An injective surjective function (bijection) An injective non-surjective function (injection, not a bijection)

An injective non-surjective function (injection, not a bijection) A non-injective non-surjective function (neither a bijection)

A non-injective non-surjective function (neither a bijection)

Surjective composition: the first function need not be surjective.

Surjective composition: the first function need not be surjective. Non-surjective functions in the Cartesian plane. Although some parts of the function are surjective, where elements y in Y do have a value x in X such that y = f(x), some parts are not. Left: There is y0 in Y, but there is no x0 in X such that y0 = f(x0). Right: There are y1, y2 and y3 in Y, but there are no x1, x2, and x3 in X such that y1 = f(x1), y2 = f(x2), and y3 = f(x3).

Non-surjective functions in the Cartesian plane. Although some parts of the function are surjective, where elements y in Y do have a value x in X such that y = f(x), some parts are not. Left: There is y0 in Y, but there is no x0 in X such that y0 = f(x0). Right: There are y1, y2 and y3 in Y, but there are no x1, x2, and x3 in X such that y1 = f(x1), y2 = f(x2), and y3 = f(x3). Interpretation for surjective functions in the Cartesian plane, defined by the mapping f : X → Y, where y = f(x), X = domain of function, Y = range of function. Every element in the range is mapped onto from an element in the domain, by the rule f. There may be a number of domain elements which map to the same range element. That is, every y in Y is mapped from an element x in X, more than one x can map to the same y. Left: Only one domain is shown which makes f surjective. Right: two possible domains X1 and X2 are shown.

Interpretation for surjective functions in the Cartesian plane, defined by the mapping f : X → Y, where y = f(x), X = domain of function, Y = range of function. Every element in the range is mapped onto from an element in the domain, by the rule f. There may be a number of domain elements which map to the same range element. That is, every y in Y is mapped from an element x in X, more than one x can map to the same y. Left: Only one domain is shown which makes f surjective. Right: two possible domains X1 and X2 are shown.

References

- "Injective, Surjective and Bijective". www.mathsisfun.com. Retrieved 2019-12-07.

- "Bijection, Injection, And Surjection | Brilliant Math & Science Wiki". brilliant.org. Retrieved 2019-12-07.

- Miller, Jeff, "Injection, Surjection and Bijection", Earliest Uses of Some of the Words of Mathematics, Tripod.

- Mashaal, Maurice (2006). Bourbaki. American Mathematical Soc. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-8218-3967-6.

- "Arrows – Unicode" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-05-11.

- Farlow, S. J. "Injections, Surjections, and Bijections" (PDF). math.umaine.edu. Retrieved 2019-12-06.

- T. M. Apostol (1981). Mathematical Analysis. Addison-Wesley. p. 35.

- Goldblatt, Robert (2006) [1984]. Topoi, the Categorial Analysis of Logic (Revised ed.). Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-45026-1. Retrieved 2009-11-25.

Further reading

- Bourbaki, N. (2004) [1968]. Theory of Sets. Elements of Mathematics. Vol. 1. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-59309-3. ISBN 978-3-540-22525-6. LCCN 2004110815.