Estonian Swedes

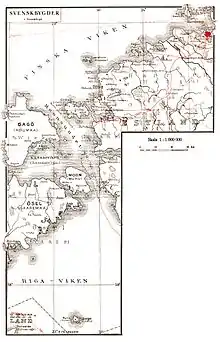

The Estonian Swedes, or Estonia-Swedes (Swedish: estlandssvenskar, colloquially aibofolke, "island people"; Estonian: eestirootslased), or "Coastal Swedes" (Estonian: rannarootslased) are a Swedish-speaking minority traditionally residing in the coastal areas and islands of what is now western and northern Estonia. The attested beginning of the continuous settlement of Estonian Swedes in these areas (known as Aiboland) dates back to the 13th and 14th centuries, when their Swedish ancestors are believed to have arrived in Estonia from what is now Sweden and Finland. During World War II, almost all of the remaining Swedish-speaking minority escaped from the Soviet invasion of Estonia and fled to Sweden in 1944. Only the descendants of a few individuals who stayed behind are permanent residents in Estonia today.

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| 26,000[1] | |

| 811[2] | |

| Languages | |

| Estonian Swedish, Estonian | |

| Religion | |

| Historically Lutheranism Predominantly irreligious | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Finland-Swedes, Swedes, Baltic Germans | |

History

Early history

The Swedish-speaking population in Estonia persisted for about 650 years. The first written mention of the Swedish population in Estonia comes from 1294, in the laws of the town of Haapsalu. Further early mentions of Swedes in Estonia came in 1341 and 1345 (when an Estonian monastery in Padise sold "the Laoküla Estate" and Suur-Pakri Island to a group of Swedes). Based on some of the place names it is possible that there was a Swedish presence in Estonia even earlier. During the 13th through 15th centuries, large numbers of Swedes arrived in coastal Estonia from Swedish-speaking parts of Finland, which was part of the Kingdom of Sweden (and would remain so until 1809), often settling on Church-owned land. The first documented record of the island of Ruhnu (Swedish: Runö), and of its Swedish population, is also a 1341 letter sent by the Bishop of Courland which confirmed the islanders' right to reside and manage their property in accordance with Swedish law.

Swedish Estonia

_en2.png.webp)

In 1561, Sweden established the Dominion of Swedish Estonia, which it would hold until 1710 (formally until 1721, when the territory was ceded to Russia under the Treaty of Nystad). The Estonia-Swedes prospered during this period. Swedish, along with German and Estonian, was one of the official languages.

Russian rule

After the Teutonic Order lost much of its power in the 16th century and the Dominion of Swedish Estonia was lost to Russia following the Great Northern War (1700–1721), conditions worsened for Swedes in Estonia: the lands they had settled were often confiscated from the Church and given to local nobility, and taxes increased. This situation remained the same during Russian rule, and the Estonian Swedes' suffering continued as, for example, the agrarian reforms which liberated the land of Estonian serfs in 1816, did not apply to Estonian (mostly non-serf) Swedes.

Forced emigrations

At certain times during Russian Estonia period, groups of Estonian Swedes were forced to leave Estonia for other parts of the Russian Empire. Most notably, Empress Catherine II of Russia forced the 1,000 Swedes of Hiiumaa (Swedish: Dagö), to move to Southern Russia (today littoral Ukraine) in 1781, where they established the community of Gammalsvenskby (today within Kherson Oblast).

Conditions improve

The Estonian Swedes' positions improved during the 1850s and 1860s, due to further agrarian reforms, but discrimination remained during the rest of the period of Tsarist rule in Estonia. After the First World War and the Russian Revolution, the independent Republic of Estonia was created in 1918. The constitution of independent Estonia granted the ethnic minority groups the control over their language of education, the right to form institutions for their national and social rights, the right to use their native language in official capacities where they formed majorities of the population, and the choice of nationality. Swedes, Baltic Germans, Russians, and Jews all had ministers in the new national government. Svenska Folkförbundet, a Swedish political organization, was formed. In 1925, a new law giving more cultural autonomy was passed, although the Russians and Swedes in Estonia did not take advantage of these new freedoms, mainly for economic reasons.

World War II

In 1939, the Soviet Union forced Estonia to sign a treaty concerning military bases. Many of the islands upon which Estonian Swedes lived were confiscated, bases were built on them, and their inhabitants were forced to leave their homes. A year later, Estonia was occupied by, and annexed into, the Soviet Union, and their voice in government was lost. Estonian Swedish men were conscripted into the Red Army and, during the German occupation, into the German armed forces. Most of the remaining Estonian Swedes fled to Sweden prior to the second occupation of Estonia by the Soviet Union in 1944. On 8 June 1945, there were 6,554 Estonian Swedes and 21,815 ethnic Estonian refugees in Sweden.[3]

Today

Today, small groups of remaining Estonian Swedes are regrouping and re-establishing their heritage, by studying Swedish language and culture. They are led by the Estonian Swedish Council, which is backed by the Estonian government. In 2000, Swedes were the 21st largest ethnic group in Estonia, numbering only 300.[4] There are however many Estonian Swedes and descendants of Estonian Swedes residing in Sweden.

Areas of population and demographics

Population figures during the early centuries of Swedish settlement are not available. At the end of the Teutonic period, there were probably around 1,000 Estonian Swedish families, with some 1,500 Swedes in the capital Tallinn (Swedish: Reval), giving a total population of roughly 5–7 thousand, some 2–3% of the population of what is now Estonia at the time.

The 1897 Russian Census gives a total Swedish population of 5,768 or 1.39% in the Governorate of Estonia. The majority of the Swedes lived in the Wiek County where they formed a minority of 5.6%.[5]

The 1922 census gives Estonia a total population of 1,107,059[6][7] of which Estonian Swedes made up only 0.7%, some 7,850 people,[6][8] who made up majorities in some places, such as Ruhnu (Swedish: Runö), Vormsi (Swedish: Ormsö), Riguldi (Swedish: Rickull). It dropped slightly to 7,641 in 1934.[9] By the time of the Second World War, the population was nearly 10,000, and roughly 9,000 of these people fled to Sweden. Towns with large pre-war Swedish populations include Haapsalu (Swedish: Hapsal) and Tallinn (Swedish: Reval).

After World War II the numbers stayed fairly stable: there were 435 Estonian Swedes in 1970, 254 in 1979 and 297 in 1989, when they placed 26th on the list of Estonia's minority groups (before the Second World War, they were third in number, after Russians and Germans). The 2000 census shows a number of 300, placing Swedes at 20th on the list of Estonia's minority groups.[4] However, only 211 of them are Estonian citizens. Since all do not claim their real ethnic background, some have estimated the real number of Estonian Swedes in Estonia to be about 1,000.[10]

Language

The Estonian Swedish dialects were part of the Eastern varieties of Swedish. There was not a unified Estonian-Swedish dialect, but several. Ruhnu had its own dialect, the Vormsi-Noarootsi-Riguldi dialect was spoken on those islands, and there was also a Pakri-Vihterpalu variety. The dialect of Hiiumaa is still spoken by a few in Gammalsvenskby, Ukraine (which is called Gammölsvänskbi in the Gammalsvenska dialect).[11]

Notable individuals

References

- "Statistika andmebaas – Vali tabel". andmed.stat.ee. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011.

- 2021. aasta rahva ja eluruumide loendus (2021 Population and Housing Census) (in Estonian and English). Vol. 2. Statistikaamet (Statistical Office of Estonia). 2021. ISBN 978-9985-74-202-0. Archived from the original on 11 June 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- Seppo Zerterberg: Viro, Historia, kansa, kulttuuri. Helsinki: Suomalaisen kirjallisuuden seura, 1995, ISBN 951-717-806-9 (in Finnish)

- 2000. Aasta rahva ja eluruumide loendus (Population and Housing Census) (in Estonian and English). Vol. 2. Statistikaamet (Statistical Office of Estonia). 2001. ISBN 9985-74-202-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- "Demoscope Weekly – Annex. Statistical indicators reference". www.demoscope.ru. Archived from the original on 22 June 2011.

- Riigi Statistika Keskbüroo (1924). "1922 a. üldrahvalugemise andmed. Vihk II. Üleriikline kokkuvõte. Tabelid" (PDF) (in Estonian). Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 15 September 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Population in counties and towns, 1922". Statistics Estonia. 12 January 2008. Archived from the original on 15 November 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- "Ethnic minorities in Estonia: past and present". Estonian Institute. 26 December 1998. Archived from the original on 3 April 2009. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- Riigi Statistika Keskbüroo (1937). "Rahvastikuprobleeme Eestis. II Rahvaloenduse tulemusi. Vihk IV" (PDF) (in Estonian). Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 15 September 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Fortbildningscentralen vid Åbo Akademi". web.abo.fi. Archived from the original on 21 August 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- "5 reasons to go to Hiiumaa out of peak season". Visitestonia.com. 2 February 2022. Archived from the original on 5 December 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

External links

- Svenska Yle Arkivet: Estlandssvenskar 1991 och 1998

- Svenska Yle Arkivet: Estlandssvenskar på Ormsö 1989

- Brief information about verbs in Estonian Swedish in the 19th century

- Estonian Institute: Estonian Swedes

- Estonian Swedes embrace cultural autonomy rights

- Ethnic Minorities in Estonia

- Gammalsvenskby: the true story of Swedish settlement in Ukraine

- Statistics Estonia: Population by Ethnic Group, Nationality, Mother Tongue, and Citizenship

- Estlandssvenskarna i Estland – har upprättat kulturellt självstyre (In Swedish)

- Karl Friedrich Wilhelm Rußwurm: Eibofolke oder die Schweden an der Küste Esthlands und auf Runö, eine ethnographische Untersuchung mit Urkunden, Tabellen und lithographirten Beilagen. Reval 1855. E-Text (In German)