Sydney Riot of 1879

The Sydney Riot of 1879 was an instance of civil disorder that occurred at an early international cricket match. It took place on 8 February 1879 at what is now the Sydney Cricket Ground (at the time known as the Association Ground), during a match between New South Wales, captained by Dave Gregory, and a touring English team, captained by Lord Harris.

The riot was sparked by a controversial umpiring decision, when star Australian batsman Billy Murdoch was given out by George Coulthard, a Victorian employed by the Englishmen. The dismissal caused an uproar among the spectators, many of whom surged onto the pitch and assaulted Coulthard and some English players. It was alleged that illegal gamblers in the New South Wales pavilion, who had bet heavily on the home side, encouraged the riot because the tourists were in a dominant position and looked set to win. Another theory given to explain the anger was that of intercolonial rivalry, that the New South Wales crowd objected to what they perceived to be a slight from a Victorian umpire.

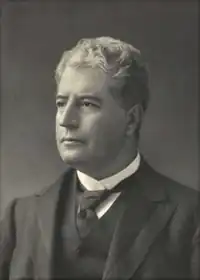

The pitch invasion occurred while Gregory halted the match by not sending out a replacement for Murdoch. The New South Wales skipper called on Lord Harris to remove umpire Coulthard, whom he considered to be inept or biased, but his English counterpart declined. The other umpire, future prime minister Edmund Barton, defended Coulthard and Lord Harris, saying that the decision against Murdoch was correct and that the English had conducted themselves appropriately. Eventually, Gregory agreed to resume the match without the removal of Coulthard. However, the crowd continued to disrupt proceedings, and play was abandoned for the day. Upon resumption after the Sunday rest day, Lord Harris's men won convincingly by an innings.

In the immediate aftermath of the riot, the England team cancelled the remaining games they were scheduled to play in Sydney. The incident also caused much press comment in England and Australia. In Australia, the newspapers were united in condemning the unrest, viewing the chaos as a national humiliation and a public relations disaster. An open letter by Lord Harris about the incident was later published in English newspapers, and caused fresh outrage in New South Wales when it was reprinted by the Australian newspapers. A defensive letter written in response by the New South Wales Cricket Association further damaged relations. The affair led to a breakdown of goodwill that threatened the future of Anglo-Australian cricket relations. However, friction between the cricketing authorities finally eased when Lord Harris agreed to lead an England representative side at The Oval in London against the touring Australians in 1880; this match became the fourth-ever Test and cemented the tradition of Anglo-Australian Test matches.

Background

England cricket tours to Australia started in 1861,[1] and while successful, were still in their infancy in 1879, despite the first Test match having been played in 1877. The teams were of variable quality; while promoters sought the best cricketers, they still had to agree to terms.[2] In addition, many could not afford the time for the long boat trip, the tour itself, and the return voyage—the journey itself often took up to two months.[3] Aside from a tour by an Australian Aboriginal team in 1868, the Dave Gregory-led campaign in 1878 was the first major Australian tour to England.[4][5][6] The tour was generally regarded as a success;[6] a highlight was the Australians' famous victory over a very strong Marylebone Cricket Club outfit, which included W. G. Grace, the dominant cricketer of the 19th century, in less than four hours.[7][8]

Keen to make the most of this success, the Melbourne Cricket Club—the Australian Board of Control for International Cricket was not created until 1905[9]—invited Lord Harris, an eminent amateur cricketer of the time, to lead a team to Australia.[10][11] The team was originally meant to be entirely amateur, but two professional Yorkshire bowlers, George Ulyett and Tom Emmett, joined the tour team after two Middlesex players had to withdraw due to a bereavement.[10] The main distinction between amateurs and professionals was social status, and although amateurs were not paid for playing, they did receive generous "expenses" which usually exceeded anything they would have been paid as professionals.[12] Despite the presence of two professionals in the team, the Englishmen were described as "Gentlemen", a euphemism for amateurs.[11] Now that Ulyett and Emmett were in the team, they did a large part of the bowling, and commentators felt that Harris had overworked them.[13]

At the time, English cricket was dominated by amateurs. Generally educated in public schools such as Harrow and Eton, and universities such as Oxford and Cambridge, to them, sport was, in a large part, a social leisure pursuit.[14] In contrast, the Australians were regarded by the social standards of the 19th century as coarse, rowdy and uncultured.[15][16] The likes of bushranger Ned Kelly heightened perceptions that Australia had a bandit culture.[16] Violence, heckling and abusive chanting among drunken spectators and gamblers at sporting grounds were commonplace in 19th century Australia,[17] and the prevalence of betting was seen as a major cause of crowd unrest.[18] There were many instances of concerning player behaviour during the 1878 tour of England, and Gregory's men were considered to be unrefined and raucous.[19]

Cheating was a regular occurrence in 19th-century Australian cricket,[20] and the inter-colonial rivalry was strong—the modern states of Australia were separate colonies until their federation in 1901.[21] As in real life, the sporting rivalry was at its most bitter between the two most populous and politically powerful colonies, New South Wales and Victoria.[22] The endless dispute between the colonies over whether Sydney or Melbourne would be the capital of Australia eventually forced the compromise that saw the construction of Canberra midway between the two cities.[23][24][25] With regards to sport, cricket administrators from both colonies sought to undermine their cross-border counterparts.[26] On the field, matches were dominated by tit-for-tat throwing wars. Both colonies sought to stack their teams with players who either had borderline—and sometimes flagrantly—illegal bowling actions to use physical intimidation as a means of negating opposition batsmen.[27] Gregory, whose action was regarded as highly dubious,[28] was prominent in his New South Wales team pursuing a policy of condoning illegal bowling.[27] It was amidst a background of inter-colonial rancour and a belligerent Australian sports culture that the riot broke out.[29]

Soon after Gregory's 1878 Australian team returned home, Lord Harris's Englishmen arrived.[11][30] Australia won the first match, played at the Melbourne Cricket Ground, by 10 wickets.[31] The match was later recognised as the third Test match in history.[31] New South Wales paceman Fred Spofforth—nicknamed "The Demon" because of his ferocious pace—took 13 wickets in the match,[32] including the first ever Test hat-trick.[33] The next tour match was against New South Wales and started on 24 January at the Association Ground in Sydney. New South Wales won by five wickets,[34] despite the absence of Spofforth—who withdrew from the home side after spraining his wrist the night before the start of the match—[31][35] and Gregory, who had been dropped for missing a training session and failing to provide an explanation for his absence.[31]

Match

The third tour match and the second game between the English XI (led by Lord Harris) and New South Wales—captained by Gregory—commenced on Friday 7 February at the Association Ground.[34] It was usual for each side to select one of the two umpires for a match. The English selected 22-year-old Victorian George Coulthard, upon a recommendation from the Melbourne Cricket Club.[29] As well as being a star footballer for Carlton,[36] Coulthard was a ground-bowler employed by Melbourne, but was yet to make his first-class cricketing debut.[37] Coulthard accompanied Harris's men from Melbourne following the Test. New South Wales selected Edmund Barton, who later became the first Prime Minister of Australia.[38]

As both Gregory and Spofforth were playing for the hosts, bookmakers were offering attractive odds against an English win, and New South Wales were heavily backed, having won the previous match with an even weaker side.[31][37] The Sydney Morning Herald condemned the "impunity with which open betting was transacted in the pavilion",[37] in defiance of the prominent notices indicating that gambling was banned.[37]

Lord Harris won the toss and chose to bat.[39] At about 12:10 pm in front of approximately 4,000 spectators,[40] A N Hornby and A. P. Lucas opened the England innings.[39] They put on 125 for the first wicket before Spofforth bowled Lucas for 51 and Hornby soon after for 67.[39] Hornby had given a chance during his innings but Lucas did not.[41] Ulyett and Harris steadied the innings after the two quick wickets and added 85; Ulyett made 55 before falling victim to a running, diving catch,[41] and Harris made 41.[39] During his innings, Harris edged a ball to wicket-keeper Murdoch, but Coulthard ruled him not out; this was noticed by the journalists present and reported the following day.[37] Spofforth cut up the wicket with his feet so badly that it became very difficult to play, and Edwin Evans, bowling from the other end, pitched nearly every ball into the marks.[40] The loss of Ulyett and Harris in quick succession triggered a sudden collapse as England lost 7/34 to be all out for 267. Evans took 5/62 and Spofforth 5/93. The English batsmen were productive against the bowling of Edwin Tindall, taking 79 runs from his 27 overs without losing a wicket.[39] At stumps on the first day, New South Wales were 2/53, with wicket-keeper and opening batsman Billy Murdoch on 28 and Hugh Massie on three.[39]

The match recommenced at noon the next day, Saturday 8 February. Ten thousand were in attendance, and New South Wales started well.[40] Murdoch and Massie took the score to 107 before the latter fell, and the hosts reached 3/130 at lunch, without losing another wicket.[39] However, wickets tumbled through the afternoon, none of the incoming batsmen passed single figures and New South Wales were all out for 177, a deficit of 90 runs.[42] Tom Emmett took the last seven wickets to end with 8/47. Murdoch batted through the innings for 82 not out, making him the hero in the eyes of the locals.[39] He hit 11 fours, and Wisden called his effort a "grand innings".[41] The prevailing rule of the time required New South Wales to follow-on (i.e. to bat again) as they were more than 80 runs in arrears.[29] New South Wales started their second innings around 4 o'clock. Then, when the New South Wales second innings score was 19, the opening partnership between Murdoch and Alick Bannerman ended when the former was adjudged run out by Coulthard for 10.[39]

Riot

Many in the crowd disagreed with the decision and took exception to it being made by an umpire employed by the Englishmen.[29] That Coulthard was a Victorian added to the emotions of the crowd, who thought along intercolonial lines. The Sydney Evening News propagated rumours that Coulthard had placed a large bet on an English victory, something that the umpire and Lord Harris later denied.[43] Loud hooting came from the pavilion, especially the section where the gamblers, who had overwhelmingly backed a New South Wales victory, were situated.[37] It was reported that well-known gamblers were prominent in inciting the other members of the crowd,[37] amid loud chants of "not out" and "Go back [to the playing field], Murdoch".[44] Gregory was later accused of trying to fan the dispute and encourage the crowd to gain an advantage for his team.[45] The crowd was already suspicious of Coulthard's competence and impartiality; the Sydney Morning Herald commented in that morning's edition, "The decision [to give Lord Harris not out on the first day] was admittedly a mistake".[29]

The pavilion stood at an angle to the crease, so the members were not in an ideal position to see how accurate the decision was.[29] The uproar continued as it became obvious that no batsman was coming out to replace Murdoch, so Harris walked towards the pavilion and met Gregory at the gate,[29] at which point Gregory asked Harris to change his umpire. Harris refused, as the English team considered the decision to be fair and correct.[29][43] Lord Harris later said that his two fielders in the point and cover positions, being side on to the crease, had a good view of the incident, and that they agreed with Coulthard's judgement.[43] Barton said that Coulthard's decision was correct, and that the Englishmen were justified in standing by their nominated umpire.[43]

It was while Harris was remonstrating with Gregory that "larrikins" in the crowd surged onto the pitch.[46] A young Banjo Paterson, who later went on to write the iconic Australian bush ballad "Waltzing Matilda", was among the pitch invaders.[47] Of the 10,000 spectators, up to 2,000 "participated in the disorder".[48] On 10 February, the Sydney Morning Herald described the number of riot participants as "not more than 2,000, at the outside, who took an active art in the disorder". On 31 May, following the publication of Harris's letter, The Argus described a significantly lesser figure, editorialising that "only a few hundred sided with the objectors. Those that were actively violent were fewer still, and they were kept in check by the better-disposed of the crowd."[49] Coulthard was jostled and Lord Harris, who had returned to the field to support Coulthard, was struck by a whip or stick but was not hurt.[47] Hornby, a keen amateur boxer who had been offered the English captaincy before stepping aside for Harris, grabbed his captain's assailant and "conveyed his prisoner to the pavilion in triumph";[29] it was later said that he had caught the wrong man.[47] Hornby was also attacked and almost lost the shirt off his back.[47] Emmett and Ulyett each took a stump for protection and escorted Lord Harris off, assisted by some members.[47] In the meantime, the crowd anger grew and there was mounting fear that the riot would intensify, due to speculation that the crowd would try to free Hornby's captive. However, there was only jostling as the players were evacuated into the pavilion, and the injuries were limited to minor cuts and bruises.[47] An English naval captain who was at the ground had his top hat pulled over his eyes and was verbally abused by some spectators.[47] After 30 minutes, the field was cleared.[43]

When the ground was finally cleared Gregory insisted, according to Harris, that Coulthard be replaced. When Harris would not agree, Gregory said, "Then the game is at an end".[38] Harris asked Barton whether he could claim the match on a forfeit. Barton replied "I will give it to you in two minutes if the batsmen don't return".[38] Harris then asked Barton to speak with Gregory to ascertain his intentions. When Barton came out he announced that Alick Bannerman and Nat Thomson would resume the New South Wales innings.[38] They walked onto the arena and reached the stumps, but before they could receive a ball, the crowd again invaded the pitch, and remained there until the scheduled end of play. According to The Sydney Mail approximately 90 minutes' play had been lost.[38] Lord Harris maintained his position on the ground, standing "erect" with "moustache bristling" among the spectators,[50] fearful that his leaving the arena would lead to a forfeit.[50]

Sunday was a rest day, so the match resumed on Monday, 10 February.[39] As it was a working day, the crowd was much smaller.[43] Rain had fallen and the sun had baked the playing surface into a sticky wicket, which caused erratic behaviour.[44] Nat Thomson was out for a duck without addition to the overnight total, and a collapse ensued.[39][51] New South Wales made only 49 in their second innings; Bannerman top-scored with 20 while six of his colleagues failed to score, while Emmett and Ulyett took four and five wickets respectively, including four wickets in four balls for the latter.[39][52] England thus won by an innings and 41 runs.[39]

Reaction

There were widespread allegations by the media and English players that the riot was started by bookmakers, or at least encouraged by the widespread betting that was known to be occurring at the match.[53] Vernon Royle, a member of the English team, wrote in his diary that "It was a most disgraceful affair and took its origin from some of the 'better' [gambling] class in the Pavilion".[54]

The Australian press and cricket officials immediately condemned the riot, which dominated the front pages of the local newspapers, even though the infamous bushranger Ned Kelly and his gang had raided Jerilderie on the same weekend.[38] The local media were united in their disgust at the scenes of tumult, fearing a public relations disaster would erupt in England.[44] The Sydney Morning Herald called the riot "a national humiliation",[38] and that it "would remain a blot upon the colony for some years to come".[38] They accused those involved in gambling of inciting "larrikins" and "roughs" to storm the field and attack the Englishmen.[43] However, they also suggested that some of the blame should be put on one of the English professionals, who "made use of a grossly insulting remark to the crowd about their being nothing but 'sons of convicts'".[43] Barton defended the Englishmen and Coulthard, saying that none had done anything wrong. He claimed that Emmett and Ulyett were incapable of insulting the Australians in such a way.[43]

The Australasian claimed that three policemen at the ground idled and allowed the rioters to attack the Englishmen.[43] They said that the riot "forever made the match memorable in the annals of New South Wales cricket",[44] and lamented the fact that "rowdyism became rampant for the rest of the afternoon".[44] The paper asked the question "What will they say in England?"[44] Wisden condemned the unrest as a "deplorably disgraceful affair" and described the spectators as a "rough and excited mob".[44] Richard Driver of the New South Wales Cricket Association (NSWCA) issued a statement of regret for what had happened to the tourists.[44]

Lord Harris

The NSWCA appealed to Lord Harris, and in reply he said he did not blame them or the cricketers of Sydney in any way, but said that "it [the riot] was an occurrence it was impossible he could forget".[44][55]

On 11 February, one day after the conclusion of the match and three days after the riot, Harris wrote a letter to one of his friends about the disturbance. It was clear that he intended the letter to be printed in the press, and it appeared in full in The Daily Telegraph on 1 April, among other London newspapers, reigniting the furore.[55] Wisden Cricketers' Almanack considered the incident of such significance that it reprinted the whole correspondence. The letter gives a detailed contemporary account of what Lord Harris thought about the riot.[56]

Lord Harris referred to the crowd as a "howling mob" and said "I have seen no reason as yet to change my opinion of Coulthard's qualities, or to regret his engagement, in which opinion I am joined by the whole team".[56] He further added that "Beyond slyly kicking me once or twice the mob behaved very well, their one cry being, 'Change your umpire'. And now for the cause of this disturbance, not unexpected, I may say, by us, for we have heard accounts of former matches played by English teams."[56] Harris further accused a New South Wales parliamentarian of assisting the gamblers in inciting the unrest, although he did not name the accusee.[56] He said

I blame the NSW Eleven for not objecting to Coulthard before the match began, if they had reason to suppose him incompetent to fulfil his duties. I blame the members of the association (many, of course, must be excepted) for their discourtesy and uncricket like behaviour to their guests; and I blame the committee and others of the association for ever permitting betting, but this last does not, of course, apply to our match only. I am bound to say they did all in their power to quell the disturbance. I don't think anything would have happened if A. Bannerman had been run out instead of Murdoch, but the latter, besides being a great favourite, deservedly I think, was the popular idol of the moment through having carried his bat out in the first innings.[56]

He further accused the Australian public of being bad losers, claiming that they were sparing in their applause upon his team's victory, and were unable to appreciate skills shown by an opposing team.[56] He summed up his feelings

To conclude, I cannot describe to you the horror we felt that such an insult should have been passed on us, and that the game we love so well, and wish to see honoured, supported, and played in an honest and manly way everywhere, should receive such desecration. I can use no milder word.[56]

Response in New South Wales

The NSWCA were outraged by Lord Harris's letter and convened a special meeting to consider their response and subsequently had their honorary secretary, Mr J.M. Gibson, write to The Daily Telegraph in reply. Gibson argued that "the misconduct of those who took possession of the wickets has been exaggerated" and that Lord Harris's account was "universally regarded here as both inaccurate and ungenerous."[56] The letter said that "We cannot allow a libel upon the people of New South Wales so utterly unfounded as this to pass without challenge".[56] It went on to accuse Harris of omitting certain facts in his account, which according to the NSWCA, depicted Australia and the cricket authorities in a poor light. These included an accusation that Harris had failed to note that the NSWCA and the media had immediately and strongly condemned the disturbance and treatment of the English visitors.[56] Gibson also criticised Lord Harris for claiming that Coulthard was "competent", while "admitting 'he had made two mistakes in our innings'", especially as Coulthard's not out ruling against Lord Harris "was openly admitted by his lordship to be a mistake" that favoured the Englishmen.[56] The letter further denied the claim that those who incited the riot were associated with the NSWCA and accused Harris of inflammatory conduct during the disorder.[56]

Certainly the conduct of Lord Harris did not tend to calm the general excitement. His lordship elbowed his way out through the crowd in a manner so violent as to invite assault. He kept his men 'exposed to the fury of the mob' for about an hour and a half upon the absurd and insulting plea that if he did not 'the other side would claim the match!'. But not one of the team received a scratch, and Mr. Hornby dragged a supposed offender of very diminutive stature through the mass to the pavilion, a hundred yards away, in triumph, and amidst general applause, with only a torn shirt as the penalty of his heroism.[56]

Spofforth, Australia's leading bowler, commented on the incident in an 1891 cricket magazine interview, but put a different slant on the cause. He thought that the English team were victims of intercolonial rivalry between New South Wales and Victoria:[57]

Then the crowd could stand it no longer and rushed on to the field, refusing to budge until the umpire was removed. I have no wish to dwell on this painful occurrence, but I should like to point out that the feeling aroused was almost entirely due to the spirit of the rivalry between the Colonies ... The umpire was Victorian, and the party spirit in the crowd was too strong, 'Let an Englishman stand umpire,' they cried; 'we don't mind any of them. We won't have a Victorian.' There was not the slightest animosity against Lord Harris or any of his team; the whole disturbance was based on the fact that the offender was a Victorian. But Lord Harris stood by his umpire; and as a result, the match had to be abandoned till the following day.[57]

Aftermath

Immediately after the game, Lord Harris led his men from Sydney, cancelling the planned return match against a representative Australian side that would have become the fourth-ever Test match.[58] The England team returned to Melbourne where two further matches were played against Victoria on 21–25 February and 7–10 March.[59] At the farewell banquet hosted by the Melbourne Cricket Club, Harris spoke publicly for the first time about the riot.[60] He was critical of the way his team had been treated by a portion of the New South Wales press, which had "unintentionally", he trusted, "but with questionable courtesy", described them "as if they were strolling actors, rather than as a party of gentlemen."[60] However, the speech was otherwise regarded as reconciliatory.[58]

The NSWCA pressed charges against two men who were charged with "having participated in the disorder".[61] Their President Richard Driver, who appeared for the prosecution, told the court that "the inmates of the Pavilion who had initiated the disturbance, including a well-known bookmaker of Victoria who was at the time ejected, had had their fees of membership returned to them, and they would never again be admitted to the ground".[61] The Sydney Morning Herald reported that the two men "expressed regret for what had occurred, and pleaded guilty" and "the Bench fined them 40 shillings, and to pay 21 shillings professional costs of the court".[62] Despite initial cynicism from journalists, the NSWCA announced a crackdown on betting on cricket matches, and it was reported that over the next 10 years, gambling at cricket matches in Sydney mainly died out.[63]

Impact on later tours

In 1880, an Australian side captained by Billy Murdoch toured England. The tourists had difficulty finding good opponents; most county sides turned them down, although Yorkshire played two unofficial matches against them.[64][65] There was a lot of bad will, exacerbated by the Australians' arrival in England at short notice, to some extent unexpectedly.[65] This was heightened by an English perception that the Australians came frequently to maximise their profits; at the time, professionalism was frowned upon.[66] In his autobiography Lord Harris wrote, "They asked no-one's goodwill in the matter, and it was felt this was a discourteous way of bursting in on our arrangements; and the result was they played scarcely any counties and were not generally recognised ... We felt we had to make a protest against too frequent visits".[55] Harris initially shunned the team and tried to avoid correspondence and meetings with them.[67] An attempt to arrange a game against an English XI for the Cricketers' Fund was turned down,[68] and public advertisements in the newspapers were shunned.[65] W.G. Grace was sympathetic to the Australians and felt that they were not to blame for the riot. He attempted to arrange a game for them at Lord's, but was rebuffed by the Marylebone Cricket Club,[65] who gave the excuse that the ground was not available.[55]

Despite it being Murdoch's wicket that started the riot, the English public were more sympathetic towards him than Gregory, and although the Australians played against weak opposition,[55] including many XVIIIs,[66][69][70][71] they attracted large crowds, leading the counties to regret their decision to snub them.[55] Eventually the secretary of Surrey, C. W. Alcock asked Lord Harris to put together a representative side to play the Australians,[72] while Grace acted as a mediator. Luckily for the Australians, Lord Harris had a personal rapport with their captain Murdoch and leading player Spofforth, especially as they shared his antipathy towards throwing.[73] An agreement was reached, and although Lord Harris was generous in agreeing to lead the side,[68] three cricketers who played in the infamous Sydney game—Hornby, Emmett and Ulyett—refused to play. Harris assembled a strong team, which included the three Grace brothers and Australia, who had not faced strong opposition and were without star bowler Fred Spofforth, went down by five wickets in front of 45,000 spectators.[74][75][76] This game, later recognised as the fourth Test in history and the first to be played in England, is more important than its result, as the custom of cricket tours between England and Australia was cemented. Overall, the tour was a financial success and an effective exercise in mending relations; the team were received by the Lord Mayor of London at the end of the tour and were given gifts.[75] Profits were healthy and public awareness of the bilateral cricketing relationship increased.[73]

Notes

- Pollard, p. 116.

- Pollard, pp. 116, 126–8.

- Pollard, pp. 128, 165.

- "Australia in England 1878". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 27 May 2007. Retrieved 8 December 2006.

- "Australia in North America 1878". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 27 May 2007. Retrieved 8 December 2006.

- Pollard, pp. 198–9.

- "Marylebone Cricket Club v Australians". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 27 May 2007. Retrieved 8 December 2006.

- Pollard, pp. 200–1.

- Haigh and Frith, foreword.

- Birley, p. 128.

- Pollard, p. 217.

- Birley, pp. 99–107.

- Pollard, p. 220.

- Birley, pp. 16–18, 52–5, 88–94.

- Sharp, p. 135.

- Pollard, p. 218.

- Sharp, pp. 139–141.

- Sharp, pp. 143–145.

- Harte, pp. 105–109.

- Cashman 1992, pp. 5–19.

- Davison, Hirst and Macintyre, pp. 243–4.

- Davison, Hirst and Macintyre, pp. 464–5, 662–3.

- Fitzgerald, pp. 80–92.

- Wigmore, pp. 20–4.

- Davison, Hirst and Macintyre, p. 108.

- Haigh and Frith, p. 16.

- Whimpress, pp. 24–34.

- Whimpress, pp. 28, 33.

- Harte, p. 110.

- Harte, pp. 107–108.

- Harte, p. 109.

- Cashman 1997, p. 283.

- Cashman 1997, p. 284.

- "Lord Harris' XI in Australia, 1878/79 – New South Wales v Lord Harris' XI, Sydney Cricket Ground – 24, 25, 27, 28 January 1879". Cricinfo. Archived from the original on 11 March 2007. Retrieved 21 August 2009.

- Cashman 1990, p. 98.

- Ross, John (1999). The Australian Football Hall of Fame. Australia: HarperCollinsPublishers. p. 54. ISBN 0-7322-6426-X.

- Pollard, p. 223.

- Harte, p. 111.

- "Lord Harris' XI in Australia, 1878/79 – New South Wales v Lord Harris' XI, Sydney Cricket Ground – 7, 8, 9, 10 February 1879". Cricinfo. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2009.

- Green, p. 818.

- Green, p. 821.

- "Cricket Controversies". Archived from the original on 16 August 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- Pollard, p. 225.

- Green, p. 819.

- Harte, pp. 110–111.

- "Lord Harris and the Sydney Cricketers!". The Brisbane Courier. 30 May 1879. p. 3. Retrieved 12 September 2009.

- Pollard, p. 224.

- "The Scene on the Sydney Cricket Ground". The Argus (from the Sydney Morning Herald). 13 February 1879. p. 6. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- "Saturday". The Argus. 31 May 1879. p. 6. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- Pollard, p. 228.

- Green, p. 820.

- Pollard, p. 226.

- Harte, pp. 109–114.

- Royle, p. 35.

- Birley, p. 129.

- Lord Harris's letter was originally published by the British newspaper, The Daily Telegraph on 1 April 1879. It, and the NSWCA response were reprinted in the 1880 edition of Wisden Cricketers' Almanack and then in Green, pp. 819–21.

- Cashman 1990, p. 99.

- Harte, p. 114.

- "England in Australia : Jan 1879". Cricinfo. Archived from the original on 1 July 2010. Retrieved 24 September 2009.

- "England V. Victoria". The Argus. 10 March 1879. pp. 5–6. Retrieved 11 September 2009.

- Harte, p. 113.

- Hutchinson, p. 45.

- Sharp, pp. 145–146.

- Harte, p. 117.

- Pollard, p. 234.

- Cashman 1990, p. 107.

- Harte, p. 116.

- Pollard, p. 236.

- "Australia in British Isles 1880 (England)". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 19 November 2008. Retrieved 27 September 2009.

- "Australia in British Isles 1880 (Ireland)". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2009.

- "Australia in British Isles 1880 (Scotland)". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2009.

- Harte, pp. 116–117.

- Pollard, p. 238.

- Cashman 1990, p. 109.

- Harte, pp. 117–8.

- Pollard, pp. 236–7.

References

- Birley, Derek (2003). A Social History of English Cricket. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 1-85410-941-3.

- Cashman, Richard (1990). The Demon Spofforth. Kensington, N.S.W.: University of New South Wales Press. ISBN 0-86840-004-1.

- Cashman, Richard (1992). O'Hara, John (ed.). Crowd Violence at Australian Sport. Campbelltown, NSW: Australian Society for Sports History. pp. 61–79. ISBN 0-646-07084-3.

- Cashman; Franks; Maxwell; Sainsbury; Stoddart; Weaver; Webster (1997). The A-Z of Australian cricketers. Melbourne, Vic.: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-550604-9.

- Davison, Graeme; Hirst, John; Macintyre, Stuart (1999). The Oxford Companion to Australian History. Melbourne, Vic.: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-553597-9.

- Egan, Jack (1991). The Story of Cricket in Australia. Sydney, N.S.W.: ABC Enterprises. ISBN 0-7333-0195-9.

- Fitzgerald, Alan (1987). Canberra in two centuries:A pictorial history. Torrens, A.C.T.: Clareville Press. ISBN 0-909278-02-4.

- Gibson, Alan (1989). The Cricket Captains of England. London: Pavilion. ISBN 1-85145-395-4.

- Green, Benny, ed. (1992). Wisden Anthology – 1864–1900. London: Queen Anne Press. ISBN 0-354-08555-7.

- Haigh, Gideon; Frith, David (2007). Inside story:unlocking Australian cricket's archives. Southbank, Vic.: News Custom Publishing. ISBN 978-1-921116-00-1.

- Lord Harris (1921). A Few Short Runs. London: John Murray.

- Harte, Chris; Whimpress, Bernard (2003). The Penguin History of Australian Cricket. Camberwell, Vic.: Andre Deutsch. ISBN 0-670-04133-5.

- Hutchinson, Garrie; Ross, John, eds. (1997). 200 Seasons of Australian Cricket. South Melbourne: Pan Macmillan Australia. pp. 44–50. ISBN 0-330-36034-5.

- Pollard, Jack (1987). The formative years of Australian cricket 1803–93. North Ryde, NSW: Angus & Robertson. ISBN 0-207-15490-2.

- Royle, Vernon (2001). Lord Harris's Team in Australia 1878–79, The Diary of Vernon Royle. London: J.W.McKenzie. ISBN 0-947821-10-4.

- Sharp, Martin (May 1988). "'A degenerate race': cricket and rugby crowds in Sydney 1890–1912". Sporting Traditions. Campbelltown, NSW: Australian Society for Sports History. 4 (2): 61–79.

- Whimpress, Bernard (2004). Chuckers: A history of throwing in Australian cricket. Belair, S.A.: Elvis Press. ISBN 0-9756746-1-7.

- Wigmore, Lionel (1971). Canberra: history of Australia's national capital. Canberra, A.C.T.: Dalton Publishing Company. ISBN 0-909906-06-8.