Sylvilagus palustris hefneri

Sylvilagus palustris hefneri, also known commonly as the Lower Keys marsh rabbit, is an endangered subspecies of marsh rabbit in the family Leporidae. The subspecies is named after Playboy founder Hugh Hefner.[2][3]

| Lower Keys marsh rabbit | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Lagomorpha |

| Family: | Leporidae |

| Genus: | Sylvilagus |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | S. p. hefneri |

| Trinomial name | |

| Sylvilagus palustris hefneri Lazell, 1984 | |

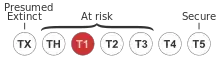

Conservation status

S. p. hefneri was federally recognized as an "endangered species" on June 21, 1990. It is affected by destruction to its habitat. The urbanized Florida Keys have left the rabbit with a very small home range, making it more vulnerable to threats such as pollution, vehicular road kill, and predation by stray cats. Forys and Humphrey (1999) predicted a gradual decline in S. p. hefneri abundance and extinction within 50 years (of 1995).[4] The Lower Keys marsh rabbit population is estimated to contain approximately 150 individuals.[5] In 2008, LaFever et al. performed viability assays to determine current extinction rates. They predicted extinction within ten years if action is not taken immediately.[6] They recommend urgent management of predatory stray cats, and restoration of marshes as possible solutions to reduce the extinction rate of S. p. hefneri.[6]

Taxonomy and etymology

The subspecies S. p. hefneri was first described in a publication in the Journal of Mammalogy in 1984 by James D. Lazell Jr, after his research was funded in part by a generous contribution from the Playboy Corporation.[7] The Lower Keys marsh rabbit was at that time named in honor of Hugh M. Hefner in recognition of the financial support received by his corporation.[5]

Size

S. p. hefneri is small-to-medium-sized, 12.6 to 15.0 in (320 to 380 mm) in length and 2.20 to 3.08 pounds (1.0 to 1.4 kg) in weight. The hind foot ranges from 2.6 to 3.1 inches (65 to 80 mm) in length, and the ear ranges from 1.8 to 2.4 inches (45 to 62 mm) in length.[8] S. p. hefneri is the smallest of the three marsh rabbit subspecies, the others being S. p. paludicola and S. p. palustris (the nominotypical subspecies). These three rabbit subspecies do not appear to be sexually dimorphic.[5]

Appearance

The pelage of S. p. hefneri is short with dark brown dorsal fur and greyish-white belly fur, and the tail is dark brown.[5] S. p. hefneri is smaller than the mainland marsh rabbit (S. p. palustris) and Upper Keys marsh rabbits (S. p. paludicola) and is distinguished by its dark fur.[5] S. p. hefneri also differs from S. p. palustris and S. p. paludicola in several cranial characteristics.[7] The Lower Keys marsh rabbit has a shorter molariform tooth row, higher and more convex frontonasal profile, broader cranium, and elongated dentary symphysis.[5]

Geographic range

S. p. hefneri has been isolated to the Lower Keys by the rise in sea level and human inhabitation to the local area.[9] This isolation may be the cause for the subspeciation from the Upper Keys marsh rabbit, S. p. paludicola.[5] Forys et al. determined the habitat occupied by S. p. hefneri to be 317 hectares (780 acres) in 1995 with 81 suitable habitats.[10] In 1996, Forys refined the habitat to be about 253 hectares (630 acres).[11] An average home range of 0.32 hectares (0.79 acres) was determined in 1999.[5] This range includes a few of the larger Lower Keys, specifically, Boca Chica, Saddlebunch, Sugarloaf, and Big Pine Keys and the small islands near these Keys.[5] From 2001 to 2005, Faulhaber et al. surveyed the predetermined habitat to establish a current habitat range.[12] They determined the median size of occupied patches was 2.1 hectares (5.2 acres) with an interquartile range of 0.8–5.0 hectares (2.0–12.4 acres).[12] This data is representative of 112 patches of occupied S. p. hefneri habitat (547.1 ha = 1,367 acres (5.53 km2) total),[12] with the note that the data represents an increased search area rather than an increased rabbit number. There was a net loss (—6) in patch occupancy between the 2001-2005 and 1988-1995 survey periods.[12] Possible reasons attributing to this loss are stray cat predation, rise in sea level, and storm surges from hurricanes.[12]

Habitat

S. p. hefneri is habitat specific, choosing higher elevations within salt marsh or freshwater marsh, but depends on herbaceous plants for food, cover and nesting.[5] This vegetation includes species such as sawgrass (Cladium jamiacense), seashore dropseed (Sporobolus virginicus), and cordgrass (Spartina spp.).[5] The Lower Keys marsh rabbit prefers areas with high amounts of clump grass, ground cover, Borrichia frutescens present, areas closer to other existing marsh rabbit populations, and areas close to large bodies of water.[10]

Foraging

S. p. hefneri is diet specific, choosing particular vegetation. However, foraging strategies are not affected by sex or seasonality.[5] The major vegetative species found in the Keys include grasses (Monanthochloe littoralis, Fimbristylis castanea); succulent herbs (Borrichia frutescens, Batis maritima, Salicornia virginica); sedges (Cyperus spp.); and sparse tree cover (Conocarpus erectus and Pithecellobium guadalupense).[5] S. p. hefneri will eat a variety of these species but it prefers Borrichia frutescens, which is common in the mid-saltmarsh area.[5] The Lower Keys marsh rabbit spends most of its time feeding in the mid-marsh and high-marsh areas.[4]

Behavior

Faulhaber et al. conducted a study in 2006 to survey the diurnal habits seen in S. p. hefneri to ultimately provide conservationists with appropriate parameters for habitat extension.[13] They determined that when S. p. hefneri was in brackish wetlands, it typically clustered together in patches of saltmarsh or buttonwoods. And when in it was freshwater wetlands, it typically clustered together in patches of freshwater hardwoods.

Reproduction

S. p. hefneri produce fewer offspring, at an average of 3.7 litters per year, compared to other marsh rabbits at 5.7 litters per year.[14] Sexual maturity in S. p. hefneri begins at about nine months of age.[5] Researchers have found that the majority of males disperse at this time, yet females remain in their home range.[5] S. p. hefneri is polygamous and does not display an apparent seasonal breeding pattern.[5]

Threats

S. p. hefneri is considered an "endangered species" and is threatened by many different sources such as habitat alteration, contaminants, vehicular traffic, dumping, poaching, predation from introduced species (such as free-roaming domestic cats,[15] dogs, feral hogs and fire ants), sea level rise, and exotic vegetation.[5] More than half the area of suitable S. p. hefneri habitat has been destroyed for construction of residential housing, commercial facilities, utility lines, roads, or other infrastructure in the Lower Keys.[5] Most of the remaining suitable habitat has been degraded by exotic invasive plants, repeated mowing, dumping of trash, and off-road vehicle use.[5]

Invasive species such as the Gambian pouched rat (Cricetomys gambianus), Boa constrictor, ball pythons (Python regius), and reticulated pythons (Malayopython reticulatus) are new threats to S. p. hefneri.[9][16] However, the greatest current exotic predator threat to S. p. hefneri is feral and free-roaming cats (Felis catus).[5][15]

Conservation

Many biologists and such have taken a close look at S. p. hefneri to determine and implement current conservation efforts. Action is currently underway at the species level and the habitat level. The most prominent method of conservation of S. p. hefneri is reintroducing the Lower Keys marsh rabbit to unoccupied but potentially suitable patches[17] Faulhaber et al. created a plan to restore or enhance key macro- and microhabitat more effectively by preventing harmful intrusion by humans, connecting isolated habitat patches, and mitigating barriers to rabbit movement.[13] LaFever et al. demonstrate the use of population viability analysis as a conservation planning tool for reducing human wildlife conflicts.[18] Crouse et al. conducted a genetic analysis comparing haplotypes in mitochondrial DNA to identify barriers in gene flow.[19]

Other possible methods into habitat conservation are:[5]

- Protection of important wildlife corridors

- Several marsh rabbit populations are linked by corridors of low marsh and mangroves. Protection of these areas will aid in avoiding negative impact on the rabbit.

- Removal of invasive exotic vegetation

- Invasive species kill undergrowth, destroying the rabbit's food, shelter and nesting sites, their removal is necessary to restoring habitat

- Fencing or barricading areas of off-road vehicle (ORV) use and/or dumping

- Improving habitat by planting or encouraging native plant species

- Monitor the status of S. p. hefneri, examine ecological processes, and increase public awareness of S. p. hefneri habitat and instill stewardship.

Species-level conservation action is as follows:[5]

- Investigate components of both occupied and unoccupied marsh rabbit habitat and determine why rabbits are present or absent

- Maintain and improve the GIS database for S. p. hefneri information

- Conduct S. p. hefneri reintroductions from natural wild populations

- Utilize federal regulatory mechanisms for protection

- Federal activities may cause jeopardy for the total population

- Control or eliminate free-roaming cat populations near rabbit habitat

- Free-roaming cats are a major threat to rabbit survival, establishing a program throughout the Lower Keys to control free roaming cats can increase their survival and colonization of restored habitats[15]

- Minimize road mortality by implementing slower speed zones and increase enforcement of existing zones, and by controlling poaching.

In popular culture

In 2023 S. p. hefneri was featured on a United States Postal Service Forever stamp as part of the Endangered Species set, based on a photograph from Joel Sartore's Photo Ark. The stamp was dedicated at a ceremony at the National Grasslands Visitor Center in Wall, South Dakota.[20]

References

- "NatureServe Explorer 2.0". explorer.natureserve.org. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- "My True Love Gave To Me ... A Bat Species!". CBS News. 9 December 2008. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- Curiosities of Biological Nomenclature

- Forys, E.A., and S.R. Humphrey. 1994. Biology of the Lower Keys marsh rabbit at Navy lands in the Lower Florida Keys. Semi-annual performance report no. 3 in files of the Florida Game and Fresh Water Fish Commission; Tallahassee, Florida.

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service [FWS]. 1994. Recovery Plan for the Lower Keys marsh rabbit. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; Atlanta, Georgia.

- LaFever, David, et al. "Predicting the Impacts of Future Sea-Level Rise on an Endangered Lagomorph." Environmental Management 40.3 (2007): 430-437.

- Lazell, J.D. Jr. "A new marsh rabbit (Sylvilagus palustris) from Florida's Lower Keys." Journal of Mammalogy 65.1 (1984): 26-33. Agricola.

- Forys, E.A., P.A. Frank, and R.S. Kautz. 1996. Recovery Actions for the Lower Keys marsh rabbit, silver rice rat, and Stock Island tree snail. Unpublished report to Florida Game and Fresh Water Fish Commission; Tallahassee, Florida.

- Reed, Robert N. (2005). "An Ecological Risk Assessment of Nonnative Boas and Pythons as Potentially Invasive Species in the United States" (PDF). Risk Analysis. 25 (3): 753–766. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.2005.00621.x. PMID 16022706. S2CID 17721075.

- Forys, E.A. 1995. Metapopulations of marsh rabbits: a population viability analysis of the Lower Keys marsh rabbit (Sylvilagus palustris hefneri). PhD. Thesis, University of Florida; Gainesville, Florida.

- Forys, E.A. 1996. Multi-Species Recovery Team meeting, April 1996.

- Faulhaber, Craig A.; et al. (2007). "Updated Distribution of the Lower Keys Marsh Rabbit". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 71 (1): 208–212. doi:10.2193/2005-651. JSTOR 4495162. S2CID 55197643.

- Faulhaber, Craig A.; et al. (2008). "Diurnal Habitat Use by Lower Keys Marsh Rabbits". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 72 (5): 1161–1167. doi:10.2193/2006-028. JSTOR 25097669. S2CID 86161255.

- Holler, Nicholas R.; Conaway, Clinton H. (1979). "Reproduction of the marsh rabbit (Sylvilagus palustris) in South Florida". Journal of Mammalogy. 60 (4): 769–777. doi:10.2307/1380192. JSTOR 1380192.

- Cove, Michael V.; Gardner, Beth; Simons, Theodore R.; O'Connell, Allan F. (2018). "Co-occurrence dynamics of endangered Lower Keys marsh rabbits and free-ranging domestic cats: Prey responses to an exotic predator removal program". Ecology and Evolution. 8 (8): 4042–4052. doi:10.1002/ece3.3954. ISSN 2045-7758. PMC 5916284. PMID 29721278.

- Perry, Neil D., et al.Perry, Neil D.; Hanson, Britta; Hobgood, Winston; Lopez, Roel L.; Okraska, Craig R.; Karem, Kevin; Damon, Inger K.; Carroll, Darin S. (2006). "New Invasive Species in Southern Florida: Gambian rat (Cricetomys gambianus)". Journal of Mammalogy. 87 (2): 262–264. doi:10.1644/05-MAMM-A-132RR.1.

- Faulhaber, Craig A., et al. "Reintroduction of Lower Keys Marsh Rabbits." Wildlife Society Bulletin 34.4 (2006): 1198-1202.

- LaFever, David H., et al. "Use of a population viability analysis to evaluate human-induced impacts and mitigation for the endangered Lower Keys marsh rabbit." Human-Wildlife Conflicts 2.2 (2008)

- Crouse, Amanda L., et al. "Population Structure of the Lower Keys Marsh Rabbit as Determined by Mitochondrial DNA Analysis." Journal of Wildlife Management 73.3 (2009): 362-367.

- "Postal Service Spotlights Endangered Species". United States Postal Service. April 19, 2023. Retrieved May 11, 2023.