Synaptosome

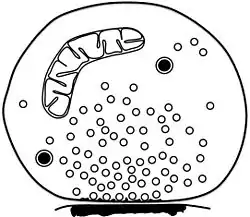

A synaptosome is an isolated synaptic terminal from a neuron. Synaptosomes are obtained by mild homogenization of nervous tissue under isotonic conditions and subsequent fractionation using differential and density gradient centrifugation. Liquid shear detaches the nerve terminals from the axon and the plasma membrane surrounding the nerve terminal particle reseals. Synaptosomes are osmotically sensitive, contain numerous small clear synaptic vesicles, sometimes larger dense-core vesicles and frequently one or more small mitochondria. They carry the morphological features and most of the chemical properties of the original nerve terminal. Synaptosomes isolated from mammalian brain often retain a piece of the attached postsynaptic membrane, facing the active zone.

| Synaptosome | |

|---|---|

Schematic of isolated synaptosome with numerous small synaptic vesicles, two dense-core vesicles, one mitochondrion and a patch of postsynaptic membrane attached to the presynaptic active zone | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D013574 |

| TH | H2.00.06.2.00033 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

Synaptosomes were first isolated in an attempt to identify the subcellular compartment corresponding to the fraction of so-called bound acetylcholine that remains when brain tissue is homogenized in iso-osmotic sucrose. Particles containing acetylcholine and its synthesizing enzyme choline acetyltransferase were originally isolated by Hebb and Whittaker (1958)[1] at the Agricultural Research Council, Institute of Animal Physiology, Babraham, Cambridge, UK. In a collaborative study with the electron microscopist George Gray from University College London, Victor P. Whittaker eventually showed that the acetylcholine-rich particles derived from guinea-pig cerebral cortex were synaptic vesicle-rich pinched-off nerve terminals.[2][3] Whittaker coined the term synaptosome to describe these fractionation-derived particles and shortly thereafter synaptic vesicles could be isolated from lysed synaptosomes.[4][5][6]

Synaptosomes are commonly used to study synaptic transmission in the test tube because they contain the molecular machinery necessary for the uptake, storage, and release of neurotransmitters. In addition they have become a common tool for drug testing. They maintain a normal membrane potential, contain presynaptic receptors, translocate metabolites and ions, and when depolarized, release multiple neurotransmitters (including acetylcholine, amino acids, catecholamines, and peptides) in a Ca2+-dependent manner. Synaptosomes isolated from the whole brain or certain brain regions are also useful models for studying structure-function relationships in synaptic vesicle release.[7] Synaptosomes can also be isolated from tissues other than brain such as spinal cord, retina, myenteric plexus or the electric ray electric organ.[8][9] Synaptosomes may be used to isolate postsynaptic densities[10] or the presynaptic active zone with attached synaptic vesicles.[11] Accordingly, various subproteomes of isolated synaptosomes, such as synaptic vesicles, synaptic membranes, or postsynaptic densities can now be studied by proteomic techniques, leading to a deeper understanding of the molecular machinery of brain neurotransmission and neuroplasticity.[12][11][13][14]

References

- Hebb CO, Whittaker VP (1958). "Intracellular distributions of acetylcholine and choline acetylase". J Physiol. 142 (1): 187–96. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1958.sp006008. PMC 1356703. PMID 13564428.

- Gray EG, Whittaker VP (1960). The isolation of synaptic vesicles from the central nervous system. J Physiol (London) 153: 35P-37P.

- Gray EG, Whittaker VP (January 1962). "The isolation of nerve endings from brain: an electron-microscopic study of cell fragments derived by homogenization and centrifugation". Journal of Anatomy. 96 (Pt 1): 79–88. PMC 1244174. PMID 13901297.

- Whittaker VP, Michaelson IA, Kirkland RJ (February 1964). "The separation of synaptic vesicles from nerve-ending particles ('synaptosomes')". The Biochemical Journal. 90 (2): 293–303. doi:10.1042/bj0900293. PMC 1202615. PMID 5834239.

- Whittaker VP (1965). "The application of subcellular fractionation techniques to the study of brain function". Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 15: 39–96. doi:10.1016/0079-6107(65)90004-0. PMID 5338099.

- Zimmermann, Herbert (2018). "Victor P. Whittaker: The Discovery of the Synaptosome and Its Implications". Synaptosomes. Neuromethods. Vol. 141. pp. 9–26. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-8739-9_2. ISBN 978-1-4939-8738-2.

- Ivannikov, M.; et al. (2013). "Synaptic vesicle exocytosis in hippocampal synaptosomes correlates directly with total mitochondrial volume". J. Mol. Neurosci. 49 (1): 223–230. doi:10.1007/s12031-012-9848-8. PMC 3488359. PMID 22772899.

- Whittaker VP (1993). "Thirty years of synaptosome research". J Neurocytol. 22 (9): 735–742. doi:10.1007/bf01181319. PMID 7903689. S2CID 138747.

- Breukel AI, Besselsen E, Ghijsen WE (1997). Synaptosomes. A model system to study release of multiple classes of neurotransmitters. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 72. pp. 33–47. doi:10.1385/0-89603-394-5:33. ISBN 0-89603-394-5. PMID 9249736.

- Carlin RK, Grab DJ, Cohen RS, Siekevitz P (September 1980). "Isolation and characterization of postsynaptic densities from various brain regions: enrichment of different types of postsynaptic densities". The Journal of Cell Biology. 86 (3): 831–45. doi:10.1083/jcb.86.3.831. PMC 2110694. PMID 7410481.

- Morciano M, Burré J, Corvey C, Karas M, Zimmermann H, Volknandt W (December 2005). "Immunoisolation of two synaptic vesicle pools from synaptosomes: a proteomics analysis". Journal of Neurochemistry. 95 (6): 1732–45. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03506.x. PMID 16269012. S2CID 33493236.

- Bai F, Witzmann FA (2007). "Synaptosome proteomics". Sub-cellular Biochemistry. 43: 77–98. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-5943-8_6. ISBN 978-1-4020-5942-1. PMC 2853956. PMID 17953392.

- Burré J, Beckhaus T, Schägger H, Corvey C, Hofmann S, Karas M, Zimmermann H, Volknandt W (December 2006). "Analysis of the synaptic vesicle proteome using three gel-based protein separation techniques". Proteomics. 6 (23): 6250–62. doi:10.1002/pmic.200600357. PMID 17080482. S2CID 24340148.

- Takamori S, Holt M, Stenius K, Lemke EA, Grønborg M, Riedel D, Urlaub H, Schenck S, Brügger B, Ringler P, Müller SA, Rammner B, Gräter F, Hub JS, De Groot BL, Mieskes G, Moriyama Y, Klingauf J, Grubmüller H, Heuser J, Wieland F, Jahn R (November 2006). "Molecular anatomy of a trafficking organelle". Cell. 127 (4): 831–46. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.030. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0012-E357-D. PMID 17110340. S2CID 6703431.