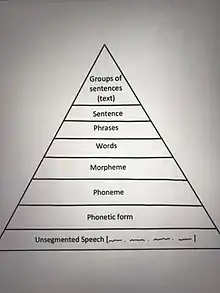

Syntactic hierarchy

Syntax is concerned with the way sentences are constructed from smaller parts, such as words and phrases. Two steps can be distinguished in the study of syntax. The first step is to identify different types of units in the stream of speech and writing. In natural languages, such units include sentences, phrases, and words. The second step is to analyze how these units build up larger patterns, and in particular to find general rules that govern the construction of sentences.http://people.dsv.su.se/~vadim/cmnew/chapter2/ch2_21.htm

This can be broken down into constituents, which are a group of words that are organized as a unit, and the organization of those constituents. They are organized in a hierarchical structure, by embedding inside one another to form larger constituents.[1]

History

Universal Grammar: the Chomskyan view

In Chomsky’s view, humans are born with innate knowledge of certain principles that guide them in developing the grammar of their language. In other words, Chomsky’s theory is that language learning is facilitated by a predisposition that our brains have for certain structures of language.[2] This implies in turn that all languages have a common structural basis: the set of rules known as "universal grammar".[3] The theory of universal grammar entails that humans are born with an innate knowledge (or structural rules) of certain principles that guide them in developing the grammar of their language.[2]

Structural Linguistics: Saussurean Influences

Regarded as the "Founder of Structural Linguistics", which reflects the concept of structuralism, Ferdinand de Saussure stated the ways in which human culture requires an overarching structure to relate to in order to communicate.[4] He defines language to be different than human speech, which is fundamental and essential to language. While speech is a combination of several disciplines (i.e. physical, psychological, etc.) and is part of an individual and their society, language is a system of classification of its own entity.[5]

De Saussure argues that in written language, words are chained together in sequence on the chain of speaking, and therefore gain relations based on the linear nature of language.[5] Language, however, is not simply a classification for universal concepts, as translating from one language to another proves to be a difficult task.[6] Each Languages organizes their own world differently, and do not name existing categories, rather articulate their own.[6] This idea explains that though languages can differ within levels of Syntactic Hierarchy, all languages encompass the same set of levels.

The Levels of Syntactic Hierarchy

Groups of sentences (text) [7]

Separate sentences can combine together to create one sentence.[7] For example, the sentence “The boy chased the ball” and “He didn’t catch it” can be combined together. You can do this in many ways including stringing one sentence after the other or joining the sentences with conjunctions.[7]

1. “The boy chased the ball; he didn’t catch it.”

2. “The boy chased the ball, but he didn’t catch it.”

3. “The boy chased the ball, and he didn’t catch it.”

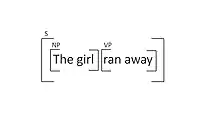

Sentence[7]

Phrases combined to form sentences.[7] The phrase “the girl” combines with the phrase “ran away” to form the sentence: “The girl ran away.”

Phrases [7]

Words combine to form phrases.[7] The word “the” combines with “girl” to form the phrase: “The girl” [7]

Words [7]

Morphemes combine to form words.[8] Morphemes belong to categories that determine how they combine.[8] For example, the word 'manageable' is made up of two morphemes 'manage' which is a verb and 'able' which is an adjective, these categories tell the morphemes how to combine so they form the word 'manageable.' [8]

Morphemes [7]

Smallest meaningful unit in a word.[8] For example, “boys” has two morphemes “boy” and “-s.”

Phonemes [7]

A unit of sound such as individual consonants and vowels of a language.[8] For example, /p/, /t/ and /æ/ are phonemes in English.

Analysis of Syntactic Hierarchy Levels

Sentence

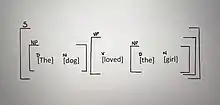

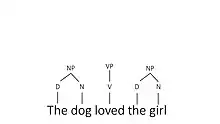

Sentences are the hierarchal structure of combined phrases. When constructing a sentence, two types of phrases are always necessary: Noun Phrase (NP) and Verb Phrase (VP), forming the simplest possible sentence.[10] What determines whether a sentence is grammatically constructed (i.e. the sentence makes sense to a native speaker of the language), is its adherence to the language's phrase structure rules, allowing a language to generate large numbers of sentences.[10] Languages cross-linguistically differ in their phrase structure rules, resulting in the difference of order of the NP and VP, and other phrases included in a sentence. Languages which do have the similar phrase structure rules, however, will translate so that a sentence from one language will be grammatical when translated into the target language.

French example:

- Sentence: "Le chien a aimé la fille" (translation: "The dog loved the girl")

The French sentence directly translates to English, demonstrating that the phrase structures of both languages are very similar.

Phrase

The idea that words combine to form phrases. For example, the word “the” combines with word “dog” to form the phrase “the dog”.[7] A phrase is a sequence of words or a group of words arranged in a grammatical way to combine and form a sentence. There are five commonly occurring types of phrases; Noun phrases (NP), Adjective phrases (AdjP), Verb phrases (VP), Adverb Phrases (AdvP), and Prepositional Phrases (PP).

Hierarchical combinations of words in their formation of phrasal categories are apparent cross-linguistically- for example, in French:

French examples:

- Noun phrase: "Le chien" (translation: "The dog")

- Verb phrase: " a aimé la fille" (translation: "loved the girl")

- Full sentence: "Le chien a aimé la fille"

Noun phrase

A noun phrase refers to a phrase that is built upon a noun. For example, “ The dog” or “the girl” in the sentence “the dog loved the girl” act as noun phrases.

Verb phrase

Verb phrase refers to a phrase that is composed of at least one main verb and one or more helping/auxiliary verb (every sentence needs at least one main verb). For example, the word “loved the girl” in the sentence “the dog loved the girl” acts as a verb phrase.

see also Adjective phrases (AdjP), Adverb phrases (AdvP), and Prepositional phrases (PP)

Phrase structure rules

A phrase structure tree shows that a sentence is both linear string of words and a hierarchical structure with phrases nested in phrases (combination of phrase structures).

A phrase structure tree is a formal device for representing speaker’s knowledge about phrase structure in speech.[11]

The syntactic category of each individual word appears immediately above that word. In this way, “the” is shown to be a determiner, “child” is a noun, and so on.

Word

The subdomain that deals with words is morphology, which states that words are made up of morphemes which combine in a regular and rule-governed fashion.[8]

For example, the word 'national' is made up of two morphemes 'nation' which is a noun and '-al' which is a suffix that means pertaining to, this meaning helps us in categorizing '-al' as an adjective. These categories aid in arranging the morphemes so they can combine in a way that will form the word 'national,’ which is an adjective.

Morphology states that words come in categories, and the morphemes that join together to create the word assign the category.[8] The two main categories are open class, where new words can be created and closed class where there is a limited number of members.[8] Within both of these categories there are further sub-categories. Open class includes: nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs, and closed class includes: prepositions, determiners, numerals, complementizers, auxiliaries, modals, coordinators, and negation/affirmation.[8] These sub categories can be further broken down for example, verbs can be either transitive or intransitive. These categories can be identified with semantic criteria about what a word means, for instance nouns are said to be people, places, or things while verbs are actions. Words are all placed in these categories and depending on their category they follow specific rules that determine their word order.[8]

Cross-Linguistically other languages form words similarly to English. This is done by having morphemes of different categories combine in a rule governed fashion in order to create the word.

French example:

- "é"- masculine past participle root verb suffix of regular -er verbs

- "aimer" (translation: to like/love)-> "aim" + "é" = "aimé" (translation: liked)

Minimalist Theory of Syntax

Syntactic hierarchy may be the most basic and assumed component of almost all syntactic theories, and yet the minimalist theory of syntax views a clause or group of words as a string, rather than as components of a hierarchical system.[12] While this theory prioritizes linearity over hierarchy, hierarchical structure is still analyzed if it "generates correct data" [12] or if there is "direct evidence for it".[12] In this way, it appears that syntactic hierarchy still plays an important role in even the minimalist theories.

Artificial language

In artificial languages, lexemes, tokens, and formulas are usually found among the basic units.[1]

Further reading

- Moles, Robert N. Legal Theory lecture Ronald Stamper and Norm based systems on the Networked Knowledge web site.

References

- Carnie, Andrew (2013) Syntax: A Generative Introduction. 3rd edition. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- "Tool Module: Chomsky's Universal Grammar". thebrain.mcgill.ca. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- "Tool Module: Chomsky's Universal Grammar". thebrain.mcgill.ca. Retrieved 2017-12-06.

- Blackburn, Simon (2008). The Oxford dictionary of philosophy (2nd ed., rev ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199541430. OCLC 191929574.

- de Saussure, Ferdinand (1915). Bally, Charles; Sechehaye, Albert (eds.). Course in General Linguistics. Translated by Baskin, Wade. McGraw-Hill Book Company. pp. 15, 123.

- Culler, Johnathon (1986). Ferdinand de Saussure. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. pp. 33.

- Burton, Strang; Dechaine, Rose-Marie; Vatikiotis-Bateson, Eric (2012). Linguistics for dummies. Ontario: Juha Wiley & Sona Canada, Ltd.

- Sportiche, Dominique; Koopman, Hilda; Stabler, Edward (2014). An Introduction to Syntactic Analysis and Theory. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 9–11. ISBN 978-1-4051-0016-8.

- Yule, George (2015). The Study of Language. United Kingdom: Cambridge University: Cambridge. p. 87. ISBN 9781107658172.

- Yule, George (2015). The Study of Language. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 87. ISBN 9781107658172.

- Borsley, Robert. D (1996). Modern phrase structure grammar. Blackwell. ISBN 0631184066.

- Dowty, David (January 27, 1989). "Toward a Minimalist Theory of Syntactic Structure". Tilburg Conference on Discontinuous Constituency: 10–62. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.453.7014.