Constitution of Syria

The current Constitution of the Syrian Arab Republic was adopted on 26 February 2012, replacing one that had been in force since 13 March 1973. The current constitution designates the state's government as a "democratic" and "republican" system. It determines Syria's identity as Arab and describes the country as a part of the wider "Arab homeland" and its people as an integral part of the Arab nation. The constitution supports the Pan-Arab programme for co-operation with other Arab nations to eventually achieve Arab Union.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Ba'athism |

|---|

|

|

|---|

|

|

History

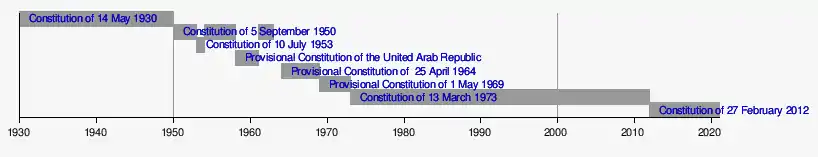

Early constitutions

The Syrian Constitution of 1930, drafted by a committee under Ibrahim Hananu, was the founding constitution of the First Syrian Republic. The constitution required the President to be of Muslim faith (article 3). It was replaced by the Constitution of 5 September 1950, which was restored following the Constitution of 10 July 1953 and the Provisional Constitution of the United Arab Republic. It was eventually replaced by the Provisional Constitution of 25 April 1964 which itself was replaced by the Provisional Constitution of 1 May 1969.

Constitution of 1973

A new constitution was adopted on 13 March 1973 and was in use until 27 February 2012. It entrenched the power of the Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party, its §8 describing the party as "the leading party in the society and the state", even if Syria was not, as is often believed, a one-party system in formal terms.[2] The constitution has been amended twice. Article 6 was amended in 1981.[3] The constitution was last amended in 2000 when the minimum age of the President was lowered from 40 to 34.[4]

Constitution of 2012

Following the 2011 Syrian revolution, Syrian government drafted a new constitution and put it to referendum on 26 February 2012, which was unmonitored by international observers. The modifications in the constitution were cosmetic and part of Ba'athist government's response to the nation-wide protests. Since the move monopolized power of the Government of Syria and was drafted without consultation outside loyalist circles, Syrian opposition and revolutionary parties boycotted the referendum, resulting in very low participation as per government data.[5] The referendum resulted in the adoption of the new constitution, which came into force on 27 February 2012.[6]

Overview

The new constitution consolidated the authoritarian structure and centralized it under a highly powerful presidency.[7] It also maintains Ba'ath party's explicitly Arab nationalist stance and advocates regional integration as a means for achieving "Arab Unity". The constitution declares Arabic as the official language of the country.[8] The Constitution is divided into 6 parts (excluding the Introduction) which are called Chapters.

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Basic Principles

- Chapter 2: Rights, Freedoms and the Rule of Law

- Chapter 3: State Authorities

- Chapter 4: The Supreme Constitutional Court

- Chapter 5: Amending the Constitution

- Chapter 6: General and Transitional Provisions

Modifications

Notable changes in the constitution include:

- It abolished the old article 8, which had entrenched the power of the Ba'ath party. The new article 8 reads: "The political system is based on the principle of political pluralism, and rule is only obtained and exercised democratically through voting", while stating that legal mechanisms "shall regulate the provisions and procedures related to the formation of political parties"[9]

- In a new article 88, it limited the term of office for the president to seven years with a maximum of one re-election.[9][10] However, Bashar al-Assad is empowered to extend his mandate beyond this time-period as per article 87, which obliges the current President to continue his rule "if no new head of state is elected".[11]

Expansion of Presidential Powers

Articles 83-150 of the new constitution increased the Presidential powers in the executive, legislature and judiciary. The executive role of the Syrian President presumes his control over all three branches, bestowing the President with unchecked powers through at least 21 articles. Some of the extraordinary powers bestowed by the 2012 Constitution that elevates the Presidential role include:[12][13][14]

- Article 97 bestows President with the authority to appoint and dismiss the Prime Minister, Council of ministers and their deputies.[15][16][17]

- "president of the republic formulates general policies of the state and oversees implementation." (Article 98).[18][19][20].

- Article 100 grants veto powers to the President to accept or reject laws passed by the legislature known as the People's Assembly[21][22]

- Article 101 charges President with the power to "pass decrees, decisions and orders". Article 113 also stipulates that the President has powers to bypass the People's Assembly to pass laws[23][24]

- Article 103 entrusts the President with the power to declare or repeal a "state of emergency" during a session with his Council of Ministers[25]

- Article 105 designates the President as "Commander in Chief of the army and armed forces" who enjoys its "absolute authority" and directly oversees "all the decisions necessary to exercise this authority."[26][27][28] These include "decisions regarding military power, declaring war and concluding peace agreements (article 102)"[29]

- "President of the Republic appoints civilian and military employees and ends their services" (Article 106)[30]

- "The President of the Republic concludes international treaties and agreements and revokes them" (Article 107)[31]

- Article 111 entitles the President to "dissolve the People’s Assembly" as per his orders[32][33][34]

- Article 112 enables the President to propose legislation to the parliament[35]

- Article 113 charges the President with the role of legislative authority if the parliament is not in session and also during the parliamentary sessions “if absolute necessity requires”.[36]

- Article 114 allows the President to take quick, extra-ordinary measures if he determines the country to be in "grave danger"[37][38]

- President can establish "special bodies, councils and committees" which operate independently of the constitutional structures (Article 115)[39][40]

- "the president of the council of ministers, his deputies and ministers are responsible before the president." (Article 121)[41]

- Article 124 empowers the President to refer the prime minister and his Council of ministers to a court of law for civil or criminal offenses. An indictment results in their suspension, and may also be accompanied by dismissal if the President decides so.[42][43]

- "Supreme Judicial Council is headed by the President of the Republic" (Article 133)[44]

- Article 141 sub-ordinates the Supreme Constitutional Court to the President[45]

Criticism

The 2012 Constitution remains un-recognized by almost all bodies of the Syrian opposition, which boycotted the referendum. The constitution was drafted by Ba'athist loyalists and was part of government attempts to monopolise its power as well as suppressing the 2011-12 Syrian protests.[46] International experts have assessed that the constitution has no "checks and balances", making it unfeasible for a political transition. Syrian opposition activists have demanded the repeal of at least 21 clauses in the Constitution which bestows unrestrained powers on the President, banishment of emergency courts and the withdrawal of more than 20 emergency edicts as the precondition to start a meaningful transition process.[47] Popular Front for Change and Liberation, the sole opposition front that had initially participated in the Syrian People's Assembly, withdrew its recognition in 2016 after Bashar al-Assad's scuttling of the Geneva negotiations.[48]

References

- "Syrian Arab Republic: Constitution, 2012". refworld. 26 February 2021. Archived from the original on 5 March 2019.

- "Syria's Assad to 'End' One-Party Rule". ibtimes.com. 15 February 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- "Amending the Syrian constitution... Achieving a quota or reaching a solution?". 18 June 2018.

- "Amending the Syrian constitution... achieving a quota or reaching a solution?". Enab Baladi. 18 June 2018. Retrieved 2020-06-03.

- Szmolk, Inmaculada (2017). Political Change in the Middle East and North Africa: After the Arab Spring. Edinburgh, United Kingdom: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-1-4744-1528 6.

- "Presidential Decree on Syria's New Constitution". Syrian Arab News Agency. 28 February 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- Szmolk, Inmaculada (2017). Political Change in the Middle East and North Africa: After the Arab Spring. Edinburgh, United Kingdom: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-1-4744-1528 6.

- "Syrian Arab Republic: Constitution, 2012". refworld. 26 February 2021. Archived from the original on 5 March 2019.

- "English Translation of the Syrian Constitution". Qordoba. 15 February 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- Constitution of the Syrian Arabic Republic, SANA, 26-02-2012

- Szmolk, Inmaculada (2017). Political Change in the Middle East and North Africa: After the Arab Spring. Edinburgh, United Kingdom: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-1-4744-1528 6.

- Szmolk, Inmaculada (2017). Political Change in the Middle East and North Africa: After the Arab Spring. Edinburgh, United Kingdom: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-1-4744-1528 6.

- Syria’s Transition: Governance & Constitutional Options Under U.N. Security Council Resolution 2254 (PDF). The Carter Center. 2016. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2023.

- "Syrian Arab Republic: Constitution, 2012". refworld. 26 February 2021. Archived from the original on 5 March 2019.

- Szmolk, Inmaculada (2017). Political Change in the Middle East and North Africa: After the Arab Spring. Edinburgh, United Kingdom: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-1-4744-1528 6.

- Syria’s Transition: Governance & Constitutional Options Under U.N. Security Council Resolution 2254 (PDF). The Carter Center. 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2023.

- "Syrian Arab Republic: Constitution, 2012". refworld. 26 February 2021. Archived from the original on 5 March 2019.

- Szmolk, Inmaculada (2017). Political Change in the Middle East and North Africa: After the Arab Spring. Edinburgh, United Kingdom: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-1-4744-1528 6.

- Syria’s Transition: Governance & Constitutional Options Under U.N. Security Council Resolution 2254 (PDF). The Carter Center. 2016. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2023.

- "Syrian Arab Republic: Constitution, 2012". refworld. 26 February 2021. Archived from the original on 5 March 2019.

- "Syrian Arab Republic: Constitution, 2012". refworld. 26 February 2021. Archived from the original on 5 March 2019.

- Szmolk, Inmaculada (2017). Political Change in the Middle East and North Africa: After the Arab Spring. Edinburgh, United Kingdom: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-1-4744-1528 6.

- "Syrian Arab Republic: Constitution, 2012". refworld. 26 February 2021. Archived from the original on 5 March 2019.

- Syria’s Transition: Governance & Constitutional Options Under U.N. Security Council Resolution 2254 (PDF). The Carter Center. 2016. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2023.

- "Syrian Arab Republic: Constitution, 2012". refworld. 26 February 2021. Archived from the original on 5 March 2019.

- Syria’s Transition: Governance & Constitutional Options Under U.N. Security Council Resolution 2254 (PDF). The Carter Center. 2016. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2023.

- "Syrian Arab Republic: Constitution, 2012". refworld. 26 February 2021. Archived from the original on 5 March 2019.

- Szmolk, Inmaculada (2017). Political Change in the Middle East and North Africa: After the Arab Spring. Edinburgh, United Kingdom: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-1-4744-1528 6.

- Szmolk, Inmaculada (2017). Political Change in the Middle East and North Africa: After the Arab Spring. Edinburgh, United Kingdom: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-1-4744-1528 6.

- "Syrian Arab Republic: Constitution, 2012". refworld. 26 February 2021. Archived from the original on 5 March 2019.

- "Syrian Arab Republic: Constitution, 2012". refworld. 26 February 2021. Archived from the original on 5 March 2019.

- Syria’s Transition: Governance & Constitutional Options Under U.N. Security Council Resolution 2254 (PDF). The Carter Center. 2016. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2023.

- "Syrian Arab Republic: Constitution, 2012". refworld. 26 February 2021. Archived from the original on 5 March 2019.

- Szmolk, Inmaculada (2017). Political Change in the Middle East and North Africa: After the Arab Spring. Edinburgh, United Kingdom: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-1-4744-1528 6.

- Szmolk, Inmaculada (2017). Political Change in the Middle East and North Africa: After the Arab Spring. Edinburgh, United Kingdom: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-1-4744-1528 6.

- Syria’s Transition: Governance & Constitutional Options Under U.N. Security Council Resolution 2254 (PDF). The Carter Center. 2016. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2023.

- Syria’s Transition: Governance & Constitutional Options Under U.N. Security Council Resolution 2254 (PDF). The Carter Center. 2016. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2023.

- "Syrian Arab Republic: Constitution, 2012". refworld. 26 February 2021. Archived from the original on 5 March 2019.

- Syria’s Transition: Governance & Constitutional Options Under U.N. Security Council Resolution 2254 (PDF). The Carter Center. 2016. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2023.

- "Syrian Arab Republic: Constitution, 2012". refworld. 26 February 2021. Archived from the original on 5 March 2019.

- Syria’s Transition: Governance & Constitutional Options Under U.N. Security Council Resolution 2254 (PDF). The Carter Center. 2016. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2023.

- Syria’s Transition: Governance & Constitutional Options Under U.N. Security Council Resolution 2254 (PDF). The Carter Center. 2016. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2023.

- "Syrian Arab Republic: Constitution, 2012". refworld. 26 February 2021. Archived from the original on 5 March 2019.

- "Syrian Arab Republic: Constitution, 2012". refworld. 26 February 2021. Archived from the original on 5 March 2019.

- Syria’s Transition: Governance & Constitutional Options Under U.N. Security Council Resolution 2254 (PDF). The Carter Center. 2016. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2023.

- Szmolk, Inmaculada (2017). Political Change in the Middle East and North Africa: After the Arab Spring. Edinburgh, United Kingdom: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-1-4744-1528 6.

- Syria’s Transition: Governance & Constitutional Options Under U.N. Security Council Resolution 2254 (PDF). The Carter Center. 2016. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2023.

- Szmolk, Inmaculada; Szmolka, Durán, Inmaculada, Marién (2017). "Chapter 17: Autocratisation, authoritarian progressions and fragmented states". Political Change in the Middle East and North Africa: After the Arab Spring. Edinburgh, United Kingdom: Edinburgh University Press. p. 416. ISBN 978-1-4744-1528 6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- The 1930 Syrian Constitution (in its French version) is integrally reproduced in: Giannini, A. (1931). Le costituzioni degli stati del vicino oriente. Istituto per l’Oriente.

- Constitution of Syria (1973) at the International Constitutional Law (ICL) Project

- Constitution of Syria (2012) (CC-BY-licensed English translation by Qordoba)

- Constitution of Syria (2012) (English translation by the Syrian Arab News Agency)