Transportation Security Administration

The Transportation Security Administration (TSA) is an agency of the United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS) that has authority over the security of transportation systems within, and connecting to the United States. It was created as a response to the September 11 attacks to improve airport security procedures and consolidate air travel security under a dedicated federal administrative law enforcement agency.[1]

TSA seal | |

TSA wordmark | |

TSA flag | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | November 19, 2001 |

| Preceding agency |

|

| Jurisdiction | Transportation systems inside, and connecting to the United States of America |

| Headquarters | Springfield, Fairfax County, Virginia U.S. |

| Employees | 54,200+ (FY 2020) |

| Annual budget | $ 9.70 billion (FY 2023) |

| Agency executives |

|

| Parent department | Department of Homeland Security |

| Website | TSA.gov |

The TSA develops broad policies to protect the U.S. transportation system, including highways, railroads, bus networks, mass transit systems, ports, pipelines, and intermodal freight facilities. It fulfills this mission in conjunction with other federal, state, local and foreign government partners. However, the TSA's primary mission is airport security and the prevention of aircraft hijacking. It is responsible for screening passengers and baggage at more than 450 U.S. airports, employing screening officers, explosives detection dog handlers, and bomb technicians in airports, and armed Federal Air Marshals and Federal Flight Deck Officers on aircraft.[2]

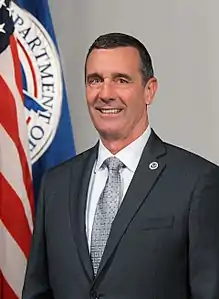

Briefly first part of the Department of Transportation, the TSA became part of DHS in March 2003. It is currently led by Administrator David Pekoske and is headquartered in Springfield, Virginia. As of the fiscal year 2023, the TSA operated on a budget of approximately $9.70 billion and employed over 47,000 Transportation Security Officers, Transportation Security Specialists, Federal Air Marshals, and other security personnel.

The TSA has screening processes and regulations related to passengers and checked and carry-on luggage, including identification verification, pat-downs, full-body scanners, and explosives screening. Since its inception the agency has been subject to criticism and controversy regarding the effectiveness of various procedures, as well as incidents of baggage theft, data security, and allegations of prejudicial treatment towards certain ethnic groups.[3]

History and mission

The TSA was created largely in response to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, which revealed weaknesses in existing airport security procedures.[4] At the time, a myriad of private security companies managed air travel security under contract to individual airlines or groups of airlines that used a given airport or terminal facility.[5] Proponents of placing the government in charge of airport security, including Transportation Secretary Norman Mineta, argued that only a single federal agency could best protect passenger aviation.

Congress agreed, and authorized the creation of the TSA in the Aviation and Transportation Security Act, which was signed into law by President George W. Bush on November 19, 2001. Bush nominated John Magaw on December 10, and he was confirmed by the Senate the following January. The agency was initially placed under the United States Department of Transportation but was moved to the Department of Homeland Security when that department was formed on March 9, 2003.

The new agency's effort to hire screeners to begin operating security checkpoints at airports represents a case of a large-scale staffing project completed over a short period. The only effort in U.S. history that came close to it was the testing of recruits for the armed forces in World War II. During the period from February to December 2002, 1.7 million applicants were assessed for 55,000 screening jobs.[6]

Administration and organization

Leadership

When TSA was part of the Department of Transportation, the head of the agency was referred to as the Undersecretary of Transportation for Security. Following the move to the Department of Homeland Security in March 2003, the position was reclassified as the administrator of the Transportation Security Administration.

There have been seven administrators and six acting administrators in the TSA's 19-year history. Several have come to the job after previously serving as Coast Guard flag officers, including Loy, Neffenger, and Pekoske.

Following the passage of the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018, which included a provision known as the TSA Modernization Act, the administrator's term was set as a five-year term retroactive to the start of current Administrator David Pekoske's term. It also made the deputy administrator a politically appointed position.[7]

| # | Picture | Name | Period | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  | John Magaw | January 28, 2002 – July 18, 2002 | Under Secretary of Transportation for Security |

| 2 |  | James Loy | July 19, 2002 – December 7, 2003 | Under Secretary of Transportation for Security until Department of Homeland Security transition. |

| 3 |  | David M. Stone | December 8, 2003 – June 3, 2005 | Acting until July 2004 when confirmed by United States Senate.[8] |

| — | Kenneth Kasprisin | June 4, 2005 – July 26, 2005 | Acting[9][10] | |

| 4 |  | Kip Hawley | July 27, 2005 – January 20, 2009 | |

| — |  | Gale Rossides | January 20, 2009 – June 24, 2010 | Acting |

| 5 | .jpg.webp) | John S. Pistole | June 25, 2010 —December 31, 2014 | |

| — |  | Melvin J. Carraway | January 1, 2015 – June 1, 2015 | Acting, reassigned to DHS Office of State and Local Law Enforcement following leak of DHS Inspector General red team test results showing screening failures at TSA checkpoints.[11][12] |

| — |  | Mark Hatfield Jr. | June 1, 2015 – June 4, 2015 | Acting[13] |

| — |  | Francis X. Taylor | June 4, 2015 – July 3, 2015 | Acting, served concurrently as Under Secretary of Homeland Security for Intelligence and Analysis. |

| 6 |  | Peter V. Neffenger | July 4, 2015 – January 20, 2017 | |

| — |  | Huban A. Gowadia | January 20, 2017 – August 10, 2017 | Acting |

| 7 |  | David Pekoske | August 10, 2017 – present[14] | Served concurrently as acting Deputy Secretary of Homeland Security from April 11 to November 13, 2019, with day-to-day operations delegated to Acting Deputy Administrator Patricia Cogswell.[15] Served concurrently as acting Secretary of Homeland Security from January 20, 2021 until Alejandro Mayorkas was confirmed by the Senate.[16] While serving as acting secretary, TSA was overseen by Executive Assistant Administrator for Security Operations Darby LaJoye.[17][18] |

Organizational structure

At the helm of the TSA is the Administrator, who leads the organization's efforts in safeguarding the nation's airports, railways, seaports, and other critical transportation infrastructure. Assisting the Administrator is a Deputy Administrator, whose role is to provide support and guidance in executing the agency's mission. In addition, the TSA benefits from the expertise and leadership of several Deputy Assistant Administrators and other executive officers, who contribute their knowledge and skills to various aspects of the agency's operations. Together, this structured leadership team forms the backbone of the TSA, working collectively to uphold and enhance the security of the nation's transportation networks. The Executive Assistant Administrator for Law Enforcement is also the Executive Director of the Federal Air Marshal Service.

Rank structure

Headquarters

- Administrator of the TSA

- Chief of Staff

- Executive Secretary

- Ombudsman

- Deputy Administrator

- Deputy Assistant Administrator

- Assistant Administrator

- Executive Director, Airport Operations

- Director, Operations Support

- Director, Airport Services

- Executive Director, Administrative Affairs

- Director, Strategic Communications & Public Affairs

- Director, Strategy, Policy Coordination & Innovation

- Director, Talent Acquisition & Human Capital

- Director, Information Technology

- Director, Training and Development

- Executive Director, Airport Operations

- Deputy Executive Assistant Administrator

- Executive Director, Law Enforcement & Federal Air Marshal Service

- Director, Flight Operations

- Director, Field Operations

- Director, Operations Management

- Executive Director, Security Operations

- Director, Domestic Aviation Operations

- Director, International Operations

- Director, Surface Operations

- Executive Director, Law Enforcement & Federal Air Marshal Service

- Executive Assistant Administrator

- Chief Counsel

- Deputy Chief Counsel

- Chief Counsel

Regional administration

- Area Director (AD)

- Regional Federal Security Director (R-FSD)

Spoke–hub or Category X airport-level administration

- Federal Security Director (FSD)

- Assistant Federal Security Director for Operations (AFSD/O)

- Assistant Federal Security Director for Screening (AFSD/S)

- Assistant Federal Security Director for Inspection (AFSD/I)

- Assistant Federal Security Director for Law Enforcement (AFSD/LE)

Airport-level

- Transportation Security Manager (TSM)

- Assistant Transportation Security Manager (ATSM)

- Supervisory Transportation Security Officer (STSO)

- Lead Transportation Security Officer (LTSO)

- Transportation Security Officer (TSO)

- Security Support Assistant (SSA)

New headquarters

In August 2017, the General Services Administration announced a new headquarters for the TSA would be built in Springfield, Virginia. The new, 625,000-square-foot headquarters was built near the outskirts of Fort Belvoir and the Franconia-Springfield Metro station, and cost $316 million.[19]

Insignia

On September 11, 2018, TSA adopted a new flag representing its core values and founding principles. The design features a white, graphically stylized American eagle sitting centrally located inside rings of red and white against a field of blue, with its dynamically feathered wings outstretched in a pose signifying protection, vigilance, and commitment. The eagle’s wings, which break through the red and white containment rings, indicate freedom of movement. There are nine stars and 11 rays emanating out from the top of the eagle to reference September 11. There is also a representation of land (roads) and sea which is representative of the modes of transportation.[20]

Operations

Finances

For fiscal year 2020, the TSA had a budget of roughly $7.68 billion.[21]

| Budget[21] | $ Million | Share |

|---|---|---|

| Operations and Support | 4,850 | 63% |

| Procurement, Construction, and Improvements | 110 | 1.4% |

| Research and Development | 23 | 0.3% |

| Not specified | 2,697 | 35% |

| Total | 7,680 | 100% |

Part of the TSA budget comes from a $5.60 per-passenger fee, also known as the September 11 Security Fee, for each one-way air-travel trip originating in the United States, not to exceed $11.20 per round-trip. In 2020, this passenger fee totaled $2.4 billion or roughly 32% of the budget allocated by Congress that year.[22]

Additionally, a small portion of TSA's budget comes from the loose change and small denomination cash left behind by travelers at airport security checkpoints, which TSA has been allowed to retain since 2005 under Section 44945 of title 49, United States Code. From FY 2008 through FY 2018, a total of $6,904,035.98 has been left behind, including a record $960,105.49 in FY 2018.[23] In fiscal year 2019, $926,030.44 was unclaimed.[24]

Airport screening

Private screening did not disappear entirely under the TSA, which allows airports to opt-out of the federal screening and hire firms to do the job instead. Such firms must still get TSA approval under its Screening Partnership Program (SPP) and follow TSA procedures.[25] Among the U.S. airports with privately operated checkpoints are San Francisco International Airport; Kansas City International Airport; Greater Rochester International Airport; Tupelo Regional Airport; Key West International Airport; Charles M. Schulz – Sonoma County Airport.[26][27] However, the bulk of airport screening in the U.S. is done by the TSA's 46,661 (as of FY 2018) Transportation Security Officers (TSOs). [28] They examine passengers and their baggage, and perform other security duties within airports, including controlling entry and exit points, and monitoring the areas near their checkpoints.

Employees

Among the types of TSA employees are:[29]

- Transportation Security Officers: The TSA employs around 47,000 Transportation Security Officers (TSOs). They screen people and property and control entry and exit points in airports. They also watch several areas before and beyond checkpoints.[30][31] TSOs do not carry weapons, and are not permitted to use force, nor do they have the power to arrest.[32]

Badge of a Transportation Security Officer

Badge of a Transportation Security OfficerTransportation Security Officers (TSOs) provide security and protection for air travelers, airports, and aircraft. This includes:

- Operating various screening equipment and technology to identify dangerous objects in baggage, cargo, and passengers, and preventing those objects from being transported onto aircraft.

- Performing searches and screening, which may include physical interaction with passengers (e.g., pat-downs, a search of property, etc.).

- Controlling terminal entry and exit points.

- Interacting with the public, giving directions, and responding to inquiries.

- Maintaining focus and awareness while working in a stressful environment which includes noise from alarms, machinery and people, crowd distractions, time pressure, and disruptive and angry passengers, to preserve the professional ability to identify and locate potentially life-threatening or mass destruction devices, and to make effective decisions in both crisis and routine situations.

- Engaging in the continuous development of critical thinking skills, necessary to mitigate actual and potential security threats, by identifying, evaluating, and applying appropriate situational options and approaches. This may include the application of risk-based security screening protocols that vary based on program requirements.

- Retaining and implementing knowledge of all applicable Standard Operating Procedures, demonstrating responsible and dependable behavior, and is open to change and adapts to new information or unexpected obstacles.[33]

The key requirements for employment are:[33]

- Be a U.S. Citizen or U.S. National at time of application submission

- Be at least 18 years of age at time of application submission

- Pass a Drug Screening and Medical Evaluation

- Pass a background investigation including a credit and criminal check

- No default on $7,500 or more in delinquent debt (but for some bankruptcies)

- Selective Service registration required

As of September 2019 the salary range for a TSO is at least $28,668 to $40,954[34] per year, not including locality pay (contiguous 48 states) or cost of living allowance in Hawaii and Alaska. A handful of airports also have a retention bonus of up to 35%.[35]

TSA passenger screening canine sniffing a passenger

TSA passenger screening canine sniffing a passenger - Behavior Detection Officers: In 2003, the TSA implemented the Screening of Passengers by Observation Technique (SPOT), which expanded across the United States in 2007. In this program, Behavior Detection Officers (BDOs), who are TSOs, observe passengers as they go through security checkpoints, looking for behaviors that might indicate a higher risk. Such passengers are subject to additional screening.[36] This program has led to concerns about, and allegations of racial profiling.[37][38] According to the TSA, SPOT screening officers are trained to observe behaviors only and not a person's appearance, race, ethnicity or religion.[39] The TSA program was reviewed in 2013 by the federal government's Government Accountability Office, which recommended cutting funds for it because there was no proof of its effectiveness.[40] The JASON scientific advisory group has also said that "no scientific evidence exists to support the detection or inference of future behavior, including intent."[41]

- Transportation Security Specialist – Explosives,[42] formerly known Bomb Appraisal Officers[43] are explosive specialists employed by TSA. These specialists are required to either be former military Explosive Ordnance Disposal Technicians who attended Naval School Explosive Ordnance Disposal or an FBI certified Public Safety Hazardous Devices Technician who attended the FBI Hazardous Devices School. Furthermore, they are required to possess at least 3 years of experience working in an EOD or bomb disposal unit. The TSS-Es provide workforce training to TSA employees, conduct an Advanced Alarm Resolution process when conventional alarm resolution has failed and serve as a liaison between TSA, law enforcement and bomb squads.[43]

- Federal Air Marshals: The Federal Air Marshal Service is the law enforcement arm of the TSA. FAMs are federal law enforcement officers who work undercover to protect the air travel system from hostile acts. As a part of the Federal Air Marshal Service, FAMs do carry weapons.[44] The FAM role, then called "sky marshalls", originated in 1961 with U.S. Customs Service (now U.S. Customs and Border Protection) following the first US hijacking.[45] It became part of the TSA following the creation of the TSA following the September 11 attacks,[44] was transferred to the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement in 2003, and back to the TSA in fiscal 2006. In July 2018, the Boston Globe reported on a secret program called "Quiet Skies", under which armed undercover marshals in airports and on planes keep tabs on passenger behaviors and movements they deemed noteworthy – including abrupt change of direction in the airport, fidgeting, having a "cold penetrating stare", changing clothes, shaving, using phones, even using the bathroom – and send detailed observations to the TSA.[46][47] The news raised concerns about Constitutional rights by groups like the ACLU and by lawmakers.[48][49]

- Federal Flight Deck Officer (FFDOs) are the airline pilots working for the U.S. airlines, who are sworn and deputized as federal law enforcement officers (FLEOs) to carry out the law enforcement duties within their specific jurisdictions (flight deck) and only from the time their aircraft doors are closed and until they are opened. FFDOs do not have arrest powers but are authorized to carry a federally issued firearm and use force (including deadly force). While the program is voluntary, only active part 121 airline pilots are eligible for the FFDO program. FFDO's are trained by the Federal Air Marshal Service and deputized by the Department of Homeland Security. Their primary goal is to work with (or without) the FAM team to defend the flight deck from hijacking, criminal violence, or any other terrorist threats to their aircraft.

- Transportation Security Inspectors (TSIs): They inspect, and investigate passenger and cargo transportation systems to see how secure they are. TSA employs roughly 1,000 aviation inspectors, 450 cargo inspectors,[50] and 100 surface inspectors.[29] As of July 2018, TSA had 97 international inspectors, are primarily responsible for performing and reporting the results of foreign airport assessments and air carrier inspections, and will provide on-site assistance and make recommendations for security enhancements.[51]

VIPR team working cars waiting to board a ferry in Portland, Maine

VIPR team working cars waiting to board a ferry in Portland, Maine - National Explosives Detection Canine Team Program: These trainers prepare dogs and handlers to serve as mobile teams that can quickly find dangerous materials. As of June 2008, the TSA had trained about 430 canine teams, with 370 deployed to airports and 56 deployed to mass transit systems.[52]

- Visible Intermodal Prevention and Response (VIPR) teams: VIPR teams started in 2005 and involved Federal Air Marshals and other TSA crew working outside of the airport environment, at train stations, ports, truck weigh stations, special events, and other places. There has been some controversy and congressional criticism for problems such as the July 3, 2007 holiday screenings. In 2011, Amtrak police chief John O'Connor moved to temporarily ban VIPR teams from Amtrak property. As of 2011, VIPR team operations were being conducted at a rate of 8,000 per year.[53]

Uniforms

In 2008, TSA officers began wearing new uniforms that have a royal blue duty shirt, dark blue (almost black) pants, and black belt.[54] The first airport to introduce the new uniforms was Baltimore-Washington International Airport. Starting on September 11, 2008, all TSOs began wearing the new uniform. One stripe on the outer edge of each shoulder board denotes a TSO, two stripes a Lead TSO, and three a Supervisory TSO.

Officers are issued badges and shoulder boards after completing a trainee period including 3-week academy at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center (FLETC) in Glynco, Georgia.

2013 Los Angeles airport shooting

On Friday, November 1, 2013, TSA officer Gerardo I. Hernandez, age 39, was shot and killed by a lone gunman at the Los Angeles International Airport. Law enforcement officials identified the suspect as 23-year-old Paul Anthony Ciancia, who was shot and wounded by law enforcement officers before being taken into custody.[55] Ciancia was wearing fatigues and carrying a bag containing a hand-written note that said he "wanted to kill TSA and pigs". Hernandez was the first TSA officer to be killed in the line of duty.[56]

2015 New Orleans airport attack

On March 21, 2015, 63-year-old Richard White entered the Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport armed with six Molotov cocktails, a gasoline lighter, and a machete. White began assaulting passengers and Transportation Security Administration officers by spraying them with a can of wasp killer, then started swinging his machete. A TSA agent blocked the machete with a piece of luggage, as White ran through a metal detector. A Jefferson Parish deputy sheriff shot and killed White as he was chasing a TSA officer with his machete.[57]

COVID-19 pandemic in the United States

TSA continued working throughout the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. As of December 31, 2020, TSA cumulatively had 4,978 federal employees test positive for COVID-19: 4,219 of those employees recovered, and 12 died as a result of the virus.[58]

Screening processes and regulations

Identification requirements

The TSA requires that passengers show a valid ID at the security checkpoint before boarding their flight. Valid forms of identification include passports from the U.S. or a foreign government, state-issued photo identification, or military ID. Passengers that do not have ID may still be allowed to fly if their identity can be verified through an alternate way.[59]

REAL ID requirements

Passed by Congress in 2005, the Real ID Act established minimum security standards for state-issued driver's licenses and identification cards and prohibits federal agencies, like TSA, from accepting licenses and identification cards for official purposes from states that do not meet these standards.[60]

Enforcement dates

Beginning January 22, 2018, driver's licenses or state IDs issued by states that are not in compliance with the REAL ID Act and have not been granted an extension by DHS may not be used to fly within the U.S.

Beginning May 7, 2025, every traveler will need a REAL ID-compliant license or state ID or another acceptable form of identification to fly within the U.S.[61]

Current list of acceptable IDs

- Driver's licenses or other state photo identity cards issued by Department of Motor Vehicles (or equivalent) per REAL ID enforcement

- U.S. passport

- United States Passport Card

- DHS trusted traveler cards (Global Entry, NEXUS, SENTRI, FAST)

- U.S. Military ID (active duty, retired military or 100% Service-connected disabled veterans and their dependents, and DoD civilians)

- Permanent resident card

- Border Crossing Card

- DHS-designated enhanced driver's license

- Airline- or airport-issued ID (if issued under a TSA-approved security plan)

- Federally recognized, tribal-issued photo ID

- HSPD-12 PIV card [62]

- Foreign government-issued passport

- Canadian provincial driver's license or Indian and Northern Affairs Canada card

- Transportation Worker Identification Credential (TWIC)

- U.S. Merchant Mariner Credential

- Immigration and Naturalization Service Employment Authorization Card (I-766)[59]

- Veteran Health Identification Card (VHIC)

Passenger names are compared against the No Fly List, a list of about 21,000 names (as of 2012) of suspected terrorists who are not allowed to board.[63] Passenger names are also compared against a longer list of "selectees"; passengers whose names match names from this list receive a more thorough screening before being potentially allowed to board.[64] The effectiveness of the lists has been widely criticized on the basis of errors in how those lists are maintained,[65] for concerns that the lists are unconstitutional, and for its ineffectiveness at stopping Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, who attempted to detonate plastic explosives in his underwear, from boarding an aircraft.[66] At the airport security checkpoint, passengers are screened to ensure they are not carrying prohibited items. These include most sorts of sharp objects, many sporting goods such as baseball bats and hockey sticks, guns or other weapons, many sorts of tools, flammable liquids (except for conventional lighters), many forms of chemicals and paint.[67] In addition, passengers are limited to 3.4 US fluid ounces (100 ml) of almost any liquid or gel, which must be presented at the checkpoint in a clear, one-quart zip-top bag.[68] These restrictions on liquids were a reaction to the 2006 transatlantic aircraft plot.

The number of passengers who have been detected bringing firearms onto airplanes in their carry-on bags has increased in recent years, from 976 in 2009 to 4,239 in 2018, according to the TSA. Indeed, a new record high for firearms found in carry-on bags has been set every year since 2008.[69] In 2010 an anonymous source told ABC News that undercover agents managed to bring weapons through security nearly 70 percent of the time at some major airports.[70] Firearms can be legally checked in checked luggage on domestic flights.[71]

In some cases, government leaders, members of the US military and law-enforcement officials are allowed to bypass security screening.[72][73]

TSA PreCheck

In a program that began in October 2011, the TSA's PreCheck Program allows selected members of American Airlines, Delta Air Lines, United Airlines, Alaska Airlines, Hawaiian Airlines, Virgin America, Southwest Airlines, Air Canada, JetBlue, and Sun Country Airlines frequent flyer programs, members of Global Entry, Free and Secure Trade (FAST), NEXUS, SENTRI and members of the US military, along with cadets and midshipmen of the United States service academies[74] to receive expedited screening for domestic and select international itineraries.[75] As of March 2019, this program was available at more than 200 airports.[76] After completing a background check, being fingerprinted,[77] and paying an $85 fee, travelers will get a Known Traveler Number. The program has led to complaints of unfairness and longer wait lines.[78] Aeromexico, Etihad Airways, Cape Air, and Seaborne Airlines joined the program bringing the total number of member carriers to 16.[79] On December 15, 2015, the program expanded to include Allegiant Air.[80] On June 21, 2016, it was announced that Frontier Airlines and Spirit Airlines will also join the program starting in the fall of 2016.[81] On August 31, 2016, the program expanded to include Lufthansa,[82] and on September 29, 2016, Frontier Airlines was added.[83] In 2017, 11 more airlines were added on January 26,[84] and another seven were added on May 25.[85] As of March 2019, a total to 65 carriers were participating in the program.

In October 2013, the TSA announced that it had begun searching a wide variety of government and private databases for information about passengers before they arrive at the airport. They did not say which databases were involved, but TSA has access to past travel itineraries, property records, physical characteristics, law enforcement, and intelligence information, among others.[86]

Large printer cartridges ban

After the October 2010 cargo planes bomb plot, in which cargo containing laser printers with toner cartridges filled with explosives were discovered on separate cargo planes, the U.S. prohibited passengers from carrying certain printer cartridges on flights.[87] The TSA said it would ban toner and ink cartridges weighing over 16 ounces (453 grams) from all passenger flights.[88][89] The ban applies to both carry-on bags and checked bags, and does not affect average travelers, whose toner cartridges are generally lighter.[89]

November 2010 enhanced screening procedures

Beginning in November 2010, TSA added new enhanced screening procedures. Passengers are required to choose between an enhanced patdown, allowing TSOs to more thoroughly check areas on the body such as waistbands, groin, and inner thigh.[72] or instead to be imaged by the use of a full body scanner (that is, either backscatter X-ray or millimeter wave detection machines) in order to fly. These changes were made in reaction to the Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab bombing attempt.[90]

Pat-downs

The new pat-down procedures, which were originally not made public,[91] "routinely involve the touching of buttocks and genitals"[92][93][94] as well as breasts.[95] These procedures were controversial, and in a November 2010 poll, 50% of those polled felt that the new pat-down procedures were too extreme, with 48% feeling them justified.[96] A number of publicized incidents created a public outcry against the invasiveness of the pat-down techniques,[97][98][99] in which women's breasts and the genital areas of all passengers are patted.[100] Pat-downs are carried out by agents of the same gender as the passenger.[101]

Concerns were raised as to the constitutionality of the new screening methods by organizations such as the American Civil Liberties Union.[102] As of April 2011, at least six lawsuits were filed for violation of the Fourth Amendment.[103][104] George Washington University law professor Jeffrey Rosen has supported this view, saying "there's a strong argument that the TSA's measures violate the Fourth Amendment, which prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures."[105] Concerns were also raised about the effects of these pat-downs on survivors of sexual assault.[106] In January 2014, Denver police launched an investigation against a screener at Denver International Airport over what the passenger stated was an intrusive patdown.[107]

Full body scanners

TSA has used two kinds of full body imaging technology since first deploying them in airports in 2010. Previously backscatter X-ray scanners were used which produced ionizing radiation. After criticism the agency now uses only millimeter wave scanners which use non-ionizing radiation.[108] The TSA refers to both systems as Advanced Imaging Technologies or AIT. Critics sometimes refer to them as "naked scanners," though operators no longer see images of the actual passenger, which has been replaced by a stick figure with boxes indicating areas of concern identified by the machine.[109][110] In 2022, TSA announced it will allow passengers to select the gender marker of their choice and alter algorithms used by the machines to be inclusive of transgender, nonbinary, and gender-nonconforming individuals. Previously the agency required screeners to select a male or female button based on a brief glance at the passenger as they entered the machine.[111]

Passengers are directed to hold their hands above their heads for a few seconds while front and back images are created.[112] If the machine indicates an anomaly to the operator, or if other problems occur, the passenger is required to receive a pat-down of that area.

Full-body scanners have also proven controversial due to privacy and health concerns. The American Civil Liberties Union has called the scanners a "virtual strip search."[114] Female passengers have complained that they are often singled out for scanning, and a review of TSA records by a local CBS affiliate in Dallas found "a pattern of women who believe that there was nothing random about the way they were selected for extra screening."[115]

The TSA, on their website, states that they have "implemented strict measures to protect passenger privacy which is ensured through the anonymity of the image,"[116] and additionally states that these technologies "cannot store, print, transmit or save the image, and the image is automatically deleted from the system after it is cleared by the remotely located security officer."[117] This claim, however, was proven false after multiple incidents involving leaked images. The machines do in fact have the ability to "save" the images and while this function is purported to be "turned off" by the TSA in screenings, TSA training facilities have the save function turned on.[118][119]

As early as 2010, the TSA began to test scanners that would produce less intrusive "stick figures".[120] In February 2011, the TSA began testing new software on the millimeter-wave machines already used at Amsterdam's Schiphol Airport that automatically detects potential threats on a passenger without the need for having an officer review actual images. Instead, one generic figure is used for all passengers and small yellow boxes are placed on areas of the body requiring additional screening.[110] The TSA announced in 2013 that the Rapiscan's backscatter scanners would no longer be used since the manufacturer of the machines could not produce "privacy software" to abstract the near-nude images that agents view and turn them into stick-like figures. The TSA continues to use other full-body scanners.[121]

Health concerns have been raised about both scanning technologies.

With regards to exposure to radiation emitted by backscatter X-rays, and there are fears that people will be exposed to a "dangerous level of radiation if they get backscattered too often". A petition by both scientists and pilots argue that the screening machines are safe.[122] Ionizing radiation is considered a non-threshold carcinogen, but it is difficult to quantify the risk of low radiation exposures.[123] Active millimeter wave scanners emit radiation which is non-ionizing, does not have enough energy to directly damage DNA, and is not known to be genotoxic.[124][125][126]

Reverse screenings

In April 2016, TSA Administrator, Peter V. Neffenger told a Senate committee that small airports had the option to use "reverse screening" – a system where passengers are not screened before boarding the aircraft at departure, but instead are screened upon arrival at the destination. The procedure is intended to save costs at airports with a limited number of flights.[127]

Reactions

After the November 2010 initiation of enhanced screening procedures of all airline passengers and flight crews, the US Airline Pilots Association issued a press release stating that pilots should not submit to full-body scanners because of unknown radiation risks and calling for strict guidelines for pat-downs of pilots, including evaluation of their fitness for duty after the pat-down, given the stressful nature of pat-downs.[100][128] Two airline pilots filed suit against the procedures.[129]

In March 2011, two New Hampshire state representatives introduced proposed legislation that would criminalize as sexual assault invasive TSA pat-downs made without probable cause.[130][131][132] In May 2011, the Texas House of Representatives passed a bill that would make it illegal for Transportation Security Administration officials to touch a person's genitals when carrying out a patdown. The bill failed in the Senate after the Department of Justice threatened to make Texas a no-fly zone if the legislation passed.[133][134] In the United States House of Representatives, Ron Paul introduced the American Traveler Dignity Act (H.R.6416),[135] but it stalled in committee.[136]

On July 2, 2010, the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) filed a lawsuit in federal court asking to halt the use of full-body scanners by the TSA on Fourth amendment grounds, and arguing that the TSA had failed to allow a public notice and rulemaking period. In July 2011, the D.C. Circuit court of appeals ruled that the TSA did violate the Administrative Procedure Act by failing to allow a public notice and comment rule-making period. The Court ordered the agency to "promptly" undertake a public notice and comment rulemaking. In July 2012, EPIC returned to court and asked the court to force enforcement; in August, the court granted the request to compel the TSA to explain its actions by the end of the month.[137] The agency responded on August 30, saying that there was "no basis whatsoever for (The DC Circuit Court's) assertion that TSA has delayed implementing this court's mandate," and said it was awaiting approval from the Department of Homeland Security before the hearings take place. The TSA also said that it was having "staffing issues" regarding the issue, but expects to begin hearings in February 2013.[138] The comment period began on March 25, 2013[139][140] and closed on June 25, 2013, with over 90% of the comments against the scanners.[140] As of October 2015, no report has been issued.

Two separate Internet campaigns promoted a "National Opt-Out Day," the day before Thanksgiving, urging travelers to "opt out" of the scanner and insist on a pat-down.[141] The enhanced pat-down procedures were also the genesis of the "Don't touch my junk" meme.[142]

March 2017 electronic device restrictions

On March 21, 2017, the TSA banned electronic devices larger than smartphones from being carried on flights to the U.S. from 10 specific airports located in Muslim-majority countries. The order cited intelligence that "indicates that terrorist groups continue to target commercial aviation and are aggressively pursuing innovative methods to undertake their attacks, to include smuggling explosive devices in various consumer items".[143][144] The restrictions were ended in July following changes in screening procedures at the specified airports.

Checked baggage

In order to be able to search passenger baggage for security screening, the TSA will cut or otherwise disable locks they cannot open themselves. The agency authorized two companies to create padlocks, lockable straps, and luggage with built-in locks that can be opened and relocked by tools and information supplied by the lock manufacturers to the TSA. These are Travel Sentry and Safe Skies Locks.[145] TSA agents sometimes cut these locks off instead of opening them, and TSA received over 3,500 complaints in 2011 about locks being tampered with.[146] Travel journalist and National Geographic Traveler editor Christopher Elliott describes these locks as "useless" at protecting the goods within,[147] whereas SmarterTravel wrote in early 2010 that the "jury is out on their effectiveness", while noting how easy they are to open.[148]

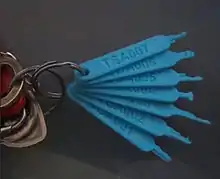

In November 2014, The Washington Post inadvertently published a photograph of all seven of the TSA master keys in an article[149] about TSA baggage handling. The photograph was later removed from the original article, but it still appears in some syndicated copies.[150] In August 2015, this gained the attention of news sites.[151] Using the photograph, security researchers and members of the public have been able to reproduce working copies of the master keys using 3D printing techniques.[152][153] The incident has prompted discussion about the security implications of using master keys.[151]

Non-Airport Regulation

While most known for their role in Airports, the TSA is also responsible for other transportation related regulations, including those without passengers. For example, the TSA was responsible for setting up cybersecurity regulations after the Colonial Pipeline ransomware attack in May 2021. As of August 2022, they issued revised cybersecurity directives for oil and gas providers more focused on performance-based measures, following extensive input from federal regulators and private industry stakeholders.[154]

Criticism and controversy

Effectiveness of screening procedures

Undercover operations to test the effectiveness of airport screening processes are routinely carried out by the TSA's Office of Investigations,[155] TSA's red team,[156] and the Department of Homeland Security Inspector General's office.

A 2004 report by the Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General found that TSA officials had collaborated with Covenant Aviation Security (CAS) at San Francisco International Airport to alert screeners to undercover tests.[157] From August 2003 until May 2004, precise descriptions of the undercover personnel were provided to the screeners. The handing out of descriptions was then stopped, but until January 2005 screeners were still alerted whenever undercover operations were being undertaken.[158] When no wrongdoing on the part of CAS was found, the contract was extended for four years. Some CAS and TSA workers received disciplinary action, but none were fired.[159][160]

A report on undercover operations conducted in October 2006 at Newark Liberty International Airport was leaked to the press. The screeners had failed 20 of 22 undercover security tests, missing numerous guns and bombs. The Government Accountability Office had previously pointed to repeated covert test failures by TSA personnel.[161][162] Revealing the results of covert tests is against TSA policy, and the agency responded by initiating an internal probe to discover the source of the leak.[163]

In July 2007, the Times Union of Albany, New York reported that TSA screeners at Albany International Airport failed multiple covert security tests conducted by the TSA. Among them was a failure to detect a fake bomb.[164]

In December 2010, ABC News Houston reported in an article about a man who accidentally took a forgotten gun through airport security, that "the failure rate approaches 70 percent at some major airports".[70]

In June 2011, TSA fired 36 screeners at the Honolulu airport for regularly allowing bags through without being inspected.[165]

In 2011, an artist, Geoff McGann, was detained by the TSA, arrested, and charged for wearing a watch which contained visible wiring and fuse-like elements, despite containing no explosive ingredients.[166]

In March 2012, American attorney Jonathan Corbett published video demonstrating a vulnerability in TSA's body scanners that would allow metallic objects to pass undetected.[167] TSA downplayed, though did not deny, the vulnerability,[168] and researchers later confirmed its existence.[169]

In May 2012, a report from the Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General stated that the TSA "does not have a complete understanding" of breaches at the nation's airports, with some hubs doing very little to fix or report security breaches. These findings will be presented to Congress.[170] Rep. Darrell Issa, then-chairman of the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee, and Rep. John Mica, then-chairman of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, were reported in 2012 to have had several joint hearings concerning the cost and benefits of the various safety programs including full-body scanners, the Transportation Worker Identification Credential (TWIC), and the behavior detection program, among others.[171]

A 2015 investigation by the Homeland Security Inspector General revealed that undercover investigators were able to smuggle banned items through checkpoints in 95% of their attempts.[172]

Some measures employed by the TSA have been accused of being ineffective and fostering a false sense of safety.[173][174] This led security expert Bruce Schneier to coin the term security theater to describe those measures.[175]

Unintended consequences of screening enhancements

Two studies by a group of Cornell University researchers asserted that increased airport security may have increased road fatalities, as would-be air travelers decide to drive and are exposed to the far greater risk of dying in a car accident.[176][177] In 2005, the researchers looked at the immediate aftermath of the attacks of September 11, 2001, and found that the change in passenger travel modes led to 242 added driving deaths per month.[176] In all, they estimated that about 1,200 driving deaths could be attributed to the short-term effects of the attacks. The study attributes the change in traveler behavior to two factors: fear of terrorist attacks and the wish to avoid the inconvenience of strict security measures; no attempt is made to estimate separately the influence of each of these two factors.

In 2007, the researchers studied the specific effects of a change to security practices instituted by the TSA in late 2002. They concluded that this change reduced the number of air travelers by 6%, and estimated that consequently, 129 more people died in car accidents in the fourth quarter of 2002.[177] Extrapolating this rate of fatalities, New York Times contributor Nate Silver remarked that this is equivalent to "four fully loaded Boeing 737s crashing each year."[178] The 2007 study also noted that strict airport security hurts the airline industry; it was estimated that the 6% reduction in the number of passengers in the fourth quarter of 2002 cost the industry $1.1 billion in lost business.[179]

Noteworthy Sexual Assaults:

TSA has garnered heavy criticism since its inception due to its pervasive practices.

I’n April 2015, NBC Denver news ran a story on two related employees coordinating amongst themselves to falsely flag attractive passengers for groping. According to NBC, while the TSA fired the employees, it took steps to protect the identity of the employees, which NBC suggested was an effort to shield them from state prosecution. The state prosecutor eventually declined to charge the individuals, as none of the unknowingly groped passengers had come forward to complain. Following the incident, Time magazine ran a story quoting a former TSA employee, who claimed groping is business as usual.[180][181]

In August 2015, a TSA agent was charged with sexual assault after assaulting a Korean Exchange Student at New York LaGuardia Airport. After the woman complied with his order to go into the restroom for further screening, the agent assaulted her. TSA in a press release after firing the worker stated passengers should be aware it does not screen people after the pass through security — this despite TSA having dogs in secure areas sniffing luggage for contraband that would require a human inspection.[182][183]

Smuggling drugs and weapons

In 2012, a number of people including TSA employees were arrested in Los Angeles Airport after they were found to be a part of a drug smuggling gang.[184]

In 2021, a TSA employee was arrested at JFK Airport after she tried to smuggle guns through a metal detector.[185]

Baggage theft

The TSA has been criticized[186] for an increase in baggage theft after its inception. Reported thefts include both valuable and dangerous goods, such as laptops, jewelry[187] guns,[188] and knives.[189] Such thefts have raised concerns that the same access might allow bombs to be placed aboard aircraft.[190]

In 2004, over 17,000 claims of baggage theft were reported.[187] As of 2004, 60 screeners had been arrested for baggage theft,[187] a number which had grown to 200 screeners by 2008.[191] 11,700 theft and damage claims were reported to the TSA in 2009, a drop from 26,500 in 2004, which was attributed to the installation of cameras and conveyor belts in airports.[192] A total of 25,016 thefts were reported over the five-year period from 2010 to 2014.

As of 2011, the TSA employed about 60,000 screeners in total (counting both baggage and passenger screening)[194] and approximately 500 TSA agents had been fired or suspended for stealing from passenger luggage since the agency's creation in November 2001. The airports with the most reported thefts from 2010 to 2014 were John F. Kennedy International Airport, followed by Los Angeles International Airport and Orlando International Airport.

In 2008, an investigative report by WTAE in Pittsburgh discovered that despite over 400 reports of baggage theft, about half of which the TSA reimbursed passengers for, not a single arrest had been made.[195] The TSA does not, as a matter of policy, share baggage theft reports with local police departments.[195]

In September 2012, ABC News interviewed former TSA agent Pythias Brown, who admitted to stealing more than $800,000 worth of items during his employment with the agency. Brown stated that it was "very convenient to steal", and that poor morale within the agency led agents to steal from passengers.[196]

in September 2023, NBC Miami ran a story regarding 3 TSA employees who were arrested for grand theft after being filmed on security cameras stealing cash, and goods from handbags.[197]

The TSA has also been criticized for not responding properly to theft and failing to reimburse passengers for stolen goods. For example, between 2011 and 2012, passengers at Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport reported $300,000 in property lost or damaged by the TSA. The agency only reimbursed $35,000 of those claims.[198] Similar statistics were found at Jacksonville International Airport – passengers reported $22,000 worth of goods missing or damaged over the course of 15 months. The TSA only reimbursed $800 total of this amount.[199]

Employee records lost or stolen

In 2007, an unencrypted computer hard drive containing Social Security numbers, bank data, and payroll information for about 100,000 employees was lost or stolen from TSA headquarters. Kip Hawley alerted TSA employees to the loss, and apologized for it. The agency asked the FBI to investigate. There were no reports that the data was later misused.[200][201]

Unsecured website

In 2007, Christopher Soghoian, a blogger and security researcher, said that a TSA website was collecting private passenger information in an unsecured manner, exposing passengers to identity theft.[202] The website allowed passengers to dispute their inclusion on the No Fly List. The TSA fixed the website several days after the press picked up the story.[203] The U.S. House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform investigated the matter,[204] and said the website had operated insecurely for more than four months, during which more than 247 people had submitted personal information.[205] The report said the TSA manager who awarded the contract for creating the website was a high-school friend and former employee of the owner of the firm that received the contract.[206] It noted:

Neither Desyne nor the Technical Lead on the traveler redress website have been sanctioned by TSA for their roles in the deployment of an insecure website. TSA continues to pay Desyne to host and maintain two major web-based information systems. TSA has taken no steps to discipline the Technical Lead, who still holds a senior program management position at TSA.[207]

In December 2009, someone within the TSA posted a sensitive manual titled "Screening Management SOP" on secret airport screening guidelines to an obscure URL on the FedBizOpps website. The manual was taken down quickly, but the breach raised questions about whether security practices had been compromised.[208] Five TSA employees were placed on administrative leave over the manual's publication, which, while redacted, had its redaction easily removed.[209]

Other criticisms

Other common criticisms of the agency have also included assertions that TSA employees have slept on the job,[210][211][212][213] bypassed security checks,[214] and failed to use good judgment and common sense.[215][216][217]

TSA agents are also accused of having mistreated passengers, and having sexually harassed passengers,[218][219][220][221] having used invasive screening procedures, including touching the genitals, along with those of children,[222] misusing body scanners to ogle female passengers,[223] having searched passengers or their belongings for items other than weapons or explosives,[224] and having stolen from passengers.[195][225][226][227][228][229][230][231] The TSA fired 28 agents and suspended 15 others after an investigation determined they failed to scan checked baggage for explosives.[232]

The TSA was also accused of having spent lavishly on events unrelated to airport security,[233] having wasted money in hiring,[234] and having had conflicts of interest.[235]

The TSA was accused of having performed poorly at the 2009 Presidential Inauguration viewing areas, which left thousands of ticket holders excluded from the event in overcrowded conditions, while those who had arrived before the checkpoints were in place avoided screening altogether.[236][237]

In 2013, dozens of TSA workers were fired or suspended for illegal gambling at Pittsburgh International Airport,[238] and eight TSA workers were arrested in connection with stolen parking passes at Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport.

A 2013, GAO report showed a 26% increase in misconduct among TSA employees between 2010 and 2012, from 2,691 cases to 3,408.[239] Another GAO report said that there is no evidence that the Screening of Passengers by Observation Techniques (SPOT) behavioral detection program, with an annual budget of hundreds of millions of dollars, is effective.[240]

A 2013 report by the Homeland Security Department Inspector General's Office charged that TSA was using criminal investigators to do the job of lower-paid employees, wasting millions of dollars a year.[241]

On December 3, 2013, the United States House of Representatives passed the Transportation Security Acquisition Reform Act (H.R. 2719; 113th Congress) in response to criticism of the TSA's acquisition process as wasteful, costly, and ineffective.[242][243] If the bill became law, it would require the TSA to develop a comprehensive technology acquisition plan and present regular reports to Congress about its successes and failures to adhere to this plan. An April 2013 report from the Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General indicated that the TSA had 17,000 items with an estimated cost of $185.7 million stored in its warehouses on May 31, 2012.[244] The auditors found that "TSA stored unusable or obsolete equipment, maintained inappropriate safety stock levels, and did not develop an inventory management process that systematically deploys equipment."[244]

In January 2014, Jason Edward Harrington, a former TSA screener at O'Hare International Airport, said that fellow staff members assigned to review body scan images of airline passengers routinely joked about fliers' weight, attractiveness, and penis and breast sizes. According to Harrington, screeners would alert each other to attractive female passengers with the code phrase "Hotel Papa" so that staff would have an opportunity to view the passengers' nude form in body scanner monitors and retaliated against rude flyers by delaying them at the checkpoint. TSA Administrator John Pistole responded by saying that all the scanners had been replaced and the screening rooms were disabled. He did not deny that the behaviors described by Harrington took place.[245]

In May 2016, actress Susan Sarandon claimed that during the entire time of the Bush administration she was "harassed every time I came into the country". She said that she hired two lawyers to contact the TSA to determine why she had been targeted but that she assumed it was because she was critical of the Bush administration. She said the harassment stopped after her attorneys followed up a second time with the TSA.[246]

In July 2018, a case heard in the Third Circuit Appeals Court ruled that TSA agents are not "investigative or law enforcement officers" and thus are not liable under the Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA). The case extended from a woman who had been detained and arrested by TSA in 2006 but later the criminal charges were acquitted in court; she had sought damages under the FTCA for damages related to the false arrest and related matters.[247]

An ACLU study found that the TSA disproportionately targets Arabs, Muslims and Latinos, despite DHS claims to the contrary.[248]

Public opinion

A CBS telephone poll of 1137 people published on November 15, 2010, found that 81% percent of those polled approved TSA's use of full-body scans.[249] An ABC/Washington Post poll conducted by Langer Associates and released November 22, 2010, found that 64% of Americans favored the full-body X-ray scanners, but that 50% think the "enhanced" pat-downs go too far; 37% felt so strongly. Besides, the poll states opposition is lowest among those who fly less than once a year.[250] A later poll by Zogby International found 61% of likely voters oppose the new measures by TSA.[251] In 2012, a poll conducted by the Frequent Business Traveler organization found that 56% of frequent fliers were "not satisfied" with the job the TSA was doing. 57% rated the TSA as doing a "poor job," and 34% rated it "fair." Only 1% of those surveyed rated the agency's work as excellent.[252] On the contrary, a 2018 Rasmussen Reports telephone poll of 1,000 Adult Americans found that 45% of respondents had an opinion of the TSA ranging from somewhat favorable to very favorable, while 39% had an unfavorable opinion.[253]

Investigations of the TSA

In 2013, The Office of Inspector General published a report titled "TSA's Actions Insufficient to Address Inspector General Recommendations to Improve its Office of Inspection". The report touched upon several topics of misconduct but the main focus of the report was of the TSA criminal investigators who received a premium on their pay despite not meeting the minimum qualification to be eligible for this pay.[254]

The TSA Office of Accountability Inspection Act of 2015 published by the Committee of Commerce, Science, and Transportation, was based on a report of an investigation that found issues with the TSA. The act also followed up the Office of Inspector General's 2013 report, mandating that the TSA should comply with Federal Regulation and correct the wage of the TSA's Criminal Investigators.[255] Had no action been taken this misuse of funds was estimated to cost taxpayers, in a span of five years, $17 million.[256]

In response, the TSA contracted a consulting firm to assist the TSA with the Office of Inspector General recommendations. However, the Office of Inspector Generals has found the TSA's response lacking as they have yet to fix a majority of the issues brought up in the report.[257]

Calls for abolition

Numerous groups and figures have called for the abolition of the TSA in its current form by persons and groups which include Sen. Rand Paul,[258] (R-KY), Rep. John Mica,[259] (R-FL), The Cato Institute,[260] Downsize DC Foundation,[261] FreedomWorks,[262] and opinion columnists from Forbes,[263] Fox News,[264] National Review,[265] USA Today,[266] Vox,[267] The Washington Examiner,[268] and The Washington Post.[269]

The TSA's critics frequently cite the agency as "ineffective, invasive, incompetent, inexcusably costly, or all four"[270] as their reasons for seeking its abolition. Those seeking to abolish the TSA have cited the improved efficacy and cost of screening provided by qualified private companies in compliance with federal guidelines.[271]

See also

- Airline complaints

- Border Force (one of the two successor agencies to the United Kingdom Border Agency; the other being UK Visas and Immigration)

- Canadian Air Transport Security Authority

- International Civil Aviation Organization

- Lost luggage

- Okoban

References

- "MINETA OUTLINES MISSION FOR TSA, SECURITY DIRECTORS". FreightWaves. January 16, 2002. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- "TSAJobs Home". hraccess.tsa.dhs.gov. Archived from the original on August 7, 2015.

- "TSA screening program risks racial profiling amid shaky science – study". the Guardian. February 8, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- "Front Matter". Criticism. 58 (3). 2016. doi:10.13110/criticism.58.3.fm. ISSN 0011-1589.

- O'Connor, Lydia (September 11, 2016). "This Is What It Was Like To Go To The Airport Before 9/11". HuffPost.

- Landy, Frank J.; Conte, Jeffery M. (December 26, 2012). Work in the 21st Century: An Introduction to Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Wiley; 4 edition. p. 263. ISBN 9781118291207.

- Goldstein, Ben (October 4, 2018). "US Transportation Security Administration reauthorized through 2021". ATWonline.com. Aviation Week. Retrieved October 23, 2018.

The bill modifies the agency's leadership structure by setting a five-year term for the administrator of TSA and makes the deputy administrator a position appointed by the president

- "Senate confirms Admiral Stone as Assistant Secretary of Homeland Security for TSA" (Press release). Washington, D.C.: Transportation Security Administration. July 23, 2004. Archived from the original on March 6, 2018. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

- "TSA Suspends 30-Minute Rule for Reagan National Airport". Transportation Security Administration. July 14, 2005. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- Becker, Andrew (February 9, 2016). "TSA official responsible for security lapses earned big bonuses". Reveal. Center for Investigative Reporting. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- "Statement By Secretary Jeh C. Johnson On The Transportation Security Administration" (Press release). Department of Homeland Security. June 1, 2015. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

- "Statement By Secretary Jeh C. Johnson On Inspector General Findings On TSA Security Screening" (Press release). Department of Homeland Security. June 1, 2015. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

- "Statement By Secretary Jeh C. Johnson On The Transportation Security Administration" (Press release). Department of Homeland Security. June 1, 2015. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

- Gayden, Greg (2017). Commercial Aviation 101 (PDF). Dallas: 443 Critical. p. 14.

- "Acting Secretary McAleenan Statement on the Designation of Administrator Pekoske to Serve as Senior Official Performing the Duties of the Deputy Secretary". Department of Homeland Security. U.S. Department of Homeland Security. April 11, 2019. Retrieved April 12, 2019.

Acting Secretary of Homeland Security Kevin K. McAleenan designated David P. Pekoske, the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) Administrator, senior official performing the duties of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Deputy Secretary. Patricia Cogswell, TSA's Acting Deputy Administrator, will oversee day-to-day operations at TSA[.]

- Megan Cassella (January 20, 2021). "Biden names his acting Cabinet". Politico. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- "TSA supports security operations for the 59th Presidential Inauguration". TSA.gov. Transportation Security Administration. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- "Security Operations". TSA.gov. Transportation Security Administration. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- Sernovitz, Daniel J. (August 24, 2017). "At long last, GSA picks a new headquarters site for the TSA". Washington Business Journal. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- Pekoske, David. "Remarks at 2018 Sept. 11 Commemoration". TSA.gov. Transportation Security Administration. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- "Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020" (PDF). govinfo.gov. United States Government Printing Office. December 20, 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 4, 2020. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

For necessary expenses of the Transportation Security Administration for operations and support, $7,680,565,000, to remain available until September 30, 2021

- "Security Fees - Transportation Security Administration". www.tsa.gov. Transportation Security Administration. Archived from the original on December 23, 2020. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

The Passenger Fee, also known as the September 11 Security Fee, is collected by air carriers from passengers at the time air transportation is purchased. Air carriers then remit the fees to TSA. The fee is currently $5.60 per one-way trip in air transportation that originates at an airport in the U.S., except that the fee imposed per round trip shall not exceed $11.20. Passenger Fee Fiscal Year 2020 Total Collection $2,456,587,000

- Gayden, Greg (2017). Commercial Aviation 101 (PDF). Dallas: 443 Critical. p. 43. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 8, 2020.

- "Unclaimed Money at Airports in Fiscal Year 2019" (PDF). www.tsa.gov. Transportation Security Administration. March 18, 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 20, 2020. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

In FY 2019, TSA collected $926,030.44. On September 30, 2019, TSA had a total of $3,618,696 in resources remaining from unclaimed money collected in FY 2019 and prior years. Of this, TSA has: Obligated $2,100,000 for training and development, of which $996,475.51 was expended during the year, and Spent $32,150 from prior-year obligations on printing and distributing bookmarks at checkpoints nationwide to publicize the TSA Pre✓® program.

- Greg Fulton (August 17, 2006). "An Airport Screener's Complaint". time.com. Time. Archived from the original on February 26, 2020. Retrieved November 19, 2010.

- TSA press release (June 18, 2002). "TSA Announces Private Security Screening Pilot Program". United States Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on September 4, 2005. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

The Aviation and Transportation Security Act, Section 108, requires TSA to establish the pilot program. The Act requires that the private screening company be owned and controlled by a citizen of the United States. The Act also sets forth the provision that TSA may terminate any contract entered into with a private screening company that has repeatedly failed to comply with any standard, regulation, directive, order, law, or contract applicable to hiring or training personnel or to the provision of screening at the airport. Also, contractors are required to meet the same employment standards and requirements as federal security screeners.

- TSA press release (January 4, 2007). "TSA Awards Private Screening Contract to US Helicopter and McNeil Security Under Screening Partnership Program". www.tsa.gov. Transportation Security Administration. Archived from the original on September 16, 2012.

Under today's unique three-party contract, US Helicopter agreed to provide for and fund all screening personnel at the East 34th Street facility through a contract negotiated with McNeil Security. TSA will provide security oversight and certified screening equipment to ensure that passengers, their accessible property, and checked baggage are thoroughly screened for explosives and other dangerous items before departure. TSA has enacted a Heliport Security Plan, which will ensure that the East 34th Street Heliport, like the Wall Street facility, adheres to all TSA regulatory requirements and applicable security directives.

- Gayden, Greg (2017). Commercial Aviation 101 (PDF). Dallas: 443 Critical. p. 16. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 8, 2020.

- "TSA's Administration Coordination of Mass Transit Security Programs" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 28, 2010. Retrieved November 19, 2010.

- "GAO-08-456T Aviation Security: Transportation Security Administration Has Strengthened Planning to Guide Investments in Key Aviation Security Programs, but More Work Remains" (PDF). Retrieved November 19, 2010.

- "TSA needs screeners at PDX". Portlandtribune.com. Archived from the original on December 25, 2008. Retrieved November 19, 2010.

- Ahlers, Mike M. (December 9, 2011). "Bill would strip TSA officers of badges in reaction to alleged strip searches". CNN. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- "Transportation Security Officer (TSO)". USAJOBS. Archived from the original on November 15, 2016. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 6, 2019. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "USAJOBS – Search Jobs". Jobsearch.usajobs.opm.gov. Archived from the original on April 24, 2011. Retrieved November 19, 2010.

- "Exclusive: TSA's Secret Behavior Checklist to Spot Terrorists". The Intercept. March 27, 2015.

- Schmidt, Michael S.; Eric Lichtblau (August 12, 2012). "Racial Profiling Rife at Airport, U.S. Officers Say". The New York Times. p. 1. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- "Report: Newark TSA screeners targeted Mexicans". CBS News. June 12, 2011. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- Zureik, Elia; Lyon, David; Abu-Laban, Yasmeen (December 13, 2010). Surveillance and Control in Israel/Palestine: Population, Territory and Power. Taylor & Francis. pp. 379–. ISBN 9780203845967. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- Tierney, John (March 23, 2014). "At Airports, a Misplaced Faith in Body Language". The New York Times.

- Weinberger, Sharon (May 27, 2010). "Intent to Deceive?" (PDF). Nature. 465 (7297): 412–415. doi:10.1038/465412a. PMID 20505706. S2CID 4350875. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- "Transportation Security Specialist-Explosives" (PDF). VA.gov. Transportation Security Administration. July 26, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- Burns, Bob (July 14, 2009). "What In the Heck Does That Person Do: TSA Bomb Appraisal Officer (BAO)". TSA.gov. Transportation Security Administration. Archived from the original on September 23, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- Grinberg, Emanuella (December 30, 2009). "Federal air marshals back in spotlight after attempted plane bombing". CNN. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- Grabell, Michael (November 13, 2008). "History of the Federal Air Marshal Service". Pro Publica. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- Winter, Jana. "In 'Quiet Skies' program, TSA is tracking regular travelers like terrorists in secret surveillance". BostonGlobe.com. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- Domonoske, Camila (July 30, 2018). "TSA's 'Quiet Skies' Program Tracks, Observes Travelers In The Air". NPR.org. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- Corbteett, Jessica. "'Creepy Violation of Constitutional Rights': TSA Uses Armed Undercover Air Marshals to Surveil Unsuspecting Travelers". Common Dreams. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- Winter, Jana. "TSA 'Quiet Skies' program has lawmakers demanding answers - The Boston Globe". BostonGlobe.com. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- "GAO-08-959T Aviation Security: Transportation Security Administration May Face Resource and Other Challenges in Developing a System to Screen All Cargo Transported on Passenger Aircraft" (PDF). Retrieved November 19, 2010.

- "GAO-19-162 Aviation Security: TSA Uses a Variety of Methods to Secure U.S.-bound Air Cargo, but Could Do More to Assess Their Effectiveness" (PDF). Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- "GAO-08-933R TSA's Explosives Detection Canine Program: Status of Increasing Number of Explosives Detection Canine Teams" (PDF). Retrieved November 19, 2010.

- Please see Visual Intermodal Prevention and Response article for references

- "TSA Management Directive No. 1100.73-2 – TSO Dress and Appearance Responsibilities" (PDF). www.tsa.gov. Transportation Security Administration. June 21, 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 22, 2012. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- Bennett, Brian; Winton, Richard; Gold, Scott (November 1, 2013). "LAX shooting: Slain TSA Officer identified as Gerardo I. Hernandez". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 17, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2013.

- Jansen, Bart (November 1, 2013). "TSA workers mourn first death on duty". USA Today. Archived from the original on October 25, 2020. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- Toppo, Greg (March 21, 2015). "New Orleans airport machete suspect is dead". USA Today. Archived from the original on July 7, 2017. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- "Coronavirus (COVID-19) information". tsa.gov/. December 31, 2020. Archived from the original on April 24, 2020.

TSA has cumulatively had 4,978 federal employees test positive for COVID-19. 4,219 employees have recovered, and 12 have unfortunately died after contracting the virus. We have also been notified that one screening contractor has passed away due to the virus

- "Identification". tsa.gov. Transportation Security Administration. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- "TSA Real ID and Air Travel" (PDF). www.tsa.gov/. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 15, 2016. Retrieved November 14, 2016.

- "REAL ID | Transportation Security Administration". www.tsa.gov. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- "What is the Homeland Security Presidential Directive - 12 (HSPD-12)? | FedIdCard".

- "No-fly list doubles in a year – now 21,000 names". CBS News. February 2, 2012. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- Alvarez, Lizette (October 22, 2008). "Terrorist watch lists shorter than previously reported". CNN. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- Schoenfeld, Gabriel (December 29, 2009). "Politics and the no-fly list". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- Tankersley, Jim (December 31, 2009). "Plane bombing plot: No-fly list procedure needs revamping, critics say". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- "Prohibited Items". tsa.gov. Transportation Security Administration. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- "3-1-1 for Carry-ons". Transportation Security Administration. Archived from the original on April 11, 2013. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- Gayden, Greg (2017). Commercial Aviation 101 (PDF). Dallas: 443 Critical. p. 23.

- Quinn, Kevin (December 17, 2010). "Man boards plane at IAH with loaded gun in carry-on". ABC News KTRK-TV/DT Houston. Retrieved May 12, 2011.

- "Transporting Firearms and Ammunition". Transportation Security Administration. Retrieved September 5, 2021.

- Sullivan, Eileen; Kellman, Laurie; Crustinger, Martin; Margasak, Larry (November 23, 2010). "TSA: Some gov't officials to skip airport security". Associated Press. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved November 23, 2010.

- O'Keefe, Ed (November 22, 2010). "Who is exempt from airport security?". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 7, 2013.

- "Military Travel". TSA.gov. Transportation Security Administration. n.d. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

All members of the U.S. Armed Forces, including those serving in the Reserves and National Guard can benefit from TSA Pre✓® expedited screening at select airports when flying on participating airlines. Cadets and midshipmen of the U.S. Military Academy, Naval Academy, Coast Guard Academy and Air Force Academy are also eligible to receive TSA Pre✓® screening benefits. Use your Department of Defense identification number when making flight reservations.

- Sharkey, Joe (November 8, 2011). "ON THE ROAD; For the Chosen Fliers, Security Check Is a Breeze". The New York Times. p. 9. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- "TSA Pre✓® Airports and Airlines". Transportation Security Administration.

- "Stuck in line: TSA PreCheck expansion slowing down frequent travelers". NBC News. Archived from the original on February 5, 2014.

- Jeff Plungis (March 22, 2013). "TSA Chief John Pistole Gets Into a Knife Fight". Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on March 24, 2013.

- "Aeromexico, Etihad, Cape Air and Seaborne join TSA PreCheck". June 3, 2016. Archived from the original on June 17, 2016. Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- "TSA Pre✓® expands to include Allegiant". Transportation Security Administration. December 15, 2015. Archived from the original on September 22, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- "Frontier Airlines to join TSA PreCheck program". June 21, 2016. Archived from the original on September 10, 2016. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- "TSA partners with Lufthansa to offer TSA Pre✓®". Transportation Security Administration. August 31, 2016. Archived from the original on September 22, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- "TSA partners with Frontier Airlines to offer TSA Pre✓®". Transportation Security Administration. September 29, 2016. Archived from the original on September 22, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- "TSA partners with 11 additional airlines to offer TSA Pre✓®". Transportation Security Administration. January 26, 2017. Archived from the original on September 22, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- "TSA Pre✓® expands to include 7 more domestic and international airlines". Transportation Security Administration. May 25, 2017. Archived from the original on September 22, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- "Security Check Now Starts Long Before You Fly". The New York Times. October 22, 2013.

- Apuzzo, Matt; Sullivan, Eileen (November 3, 2010). "Officials suspect Sept. dry run for bomb plot". The Washington Post. Associated Press. Retrieved November 2, 2010.

- "UK: Plane Bombs Explosions Were Possible Over U.S". Fox News. Archived from the original on March 29, 2012. Retrieved November 17, 2010.

- Hoffman, Tony (November 8, 2010). "U.S. Bans Large Printer Ink, Toner Cartridges on Inbound Flights". PC Mag. Retrieved November 17, 2010.

- Martin, Hugo (November 23, 2010). "Poll finds 61% oppose new airport security measures". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 7, 2013.

- Saletan, William (November 23, 2010). "The government's secret plan to feel you up at airports". Slate. Retrieved April 7, 2013.