Tadamichi Kamaya

Tadamichi Kamaya (Japanese: 釜屋忠道, Hepburn: Kamaya Tadamichi, November 4, 1862 – January 19, 1939), also known as Kamaya Chūdō was a Japanese Vice Admiral and Banker of the First Sino-Japanese War and the Russo-Japanese War. He was known for commanding the Sado Maru during the Battle of Tsushima and was the chairman of the Asahi Shinkin Bank in his later years.

Tadamichi Kamaya 釜屋忠道 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | November 4, 1862 Yonezawa, Dewa, Japan |

| Died | January 19, 1939 (aged 76) Miura District, Kanagawa, Japan |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | |

| Years of service | 1884–1915 |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | Tatsuta Sado Maru |

| Battles/wars | First Sino-Japanese War Russo-Japanese War |

| Alma mater | Imperial Japanese Naval Academy |

| Other work | Banker |

Military education and early career

Born at Yonezawa in 1862, Kamaya graduated from the 11th class of the Imperial Japanese Naval Academy on December 22, 1884.[1] Tadamichi's younger brother, Rokuro Kamaya would later graduate from the 14th Class and entered the Marine Corps which would later be known as the Yonezawa Navy. After graduation, Kamaya became an officer specializing in torpedoes and served as an instructor at the torpedo training center and as the leader of the torpedo crew.

Signaling improvements

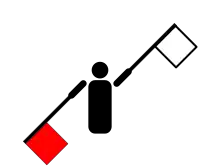

In 1889, Kamaya, who was a second lieutenant of the crew of the Fusō, learnt that Ryokitsu Arima was conducting experimental research to develop a new flag signal using the katakana syllabary from the conventional flag signal. Seeing this, Kamaya succeeded in developing the "simplest null" hand flag signal by using the katakana strokes.[2] Kamaya then developed an interest in the "kasa signal" which was used by sailors working in Kiba near his birthplace, and was thinking of developing a signal method using this.[3] The hand flag signals developed by both men were introduced to the Imperial Japanese Navy on 1889 and four years later, it was also introduced in the Imperial Japanese Army and functioned during the First Sino-Japanese War and would later become a requirement for all future officers of the Imperial Japanese Navy to master.

First Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese Wars

In June 1894, he became a staff officer of the Standing Fleet. With the First Sino-Japanese War just around the corner, under the command of Sukeyuki Itō, in July, the first Combined Fleet in the history of the Imperial Japanese Navy was organized and Kamaya was transferred to the staff of the 1st Guerrilla Unit along with Shizuka Nakamura. During the initial phases of the Russo-Japanese War, Kamaya participated in the Battle of the Yellow Sea, earning the Order of the Golden Kite, 5th Class.[4]

On May 15, 1904, Kamaya was given command of the Tatsuta which was under the 1st Squadron under Baron Tokioki Nashiba and was on guard outside Port Arthur due to the blockade of the Russian Pacific Squadron. Her consort ships were the Hatsuse, Yashima, Shikishima and the Kasagi but the Hatsuse and Yashima were struck by water mines laid by the Amur and sank. Kamaya rescued the crew of Hatsuse and repelled the sortied Russian destroyers as while the Hatsuse killed 452,[5] the Tatsuta rescued 214 people, including Commander Nashiba.[6] Masanori Ito described Kamaya's activities as "the success of Daido" despite the concern that they may be attacked by Russian submarines.[7] However, on the way back from this operation, the Tatsuta ran aground due to fog. This reefing work was successful under the guidance of Isao Miura. The Tatsuta underwent repairs at the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal and returned in early September. She engaged in the blockade of Port Arthur and returned with the fall of the fort in January 1905. Regarding Kamaya's measures to rescue the crew of Hatsuse, there were some opinions in the Central Navy that the preservation of Tatsuta should've been prioritized over the rescue. This opinion was partially based on misrepresentation and Kamaya followed the commander's instructions with the Tatsuta staying which resulted in its explosion by a naval mine and choosing the route through which the Shikishima passed.[7]

Kamaya then became the captain of the cruiser Sado Maru and participated in the Battle of Tsushima in 1905. On May 23, 1905, in preparation for the passage of the Baltic Fleet through the Straits of Tsushima, the Sado Maru, which was on patrol duty, reported the discovery of the Baltic Fleet by "Tatata point 183" which was sortieed from Jinhae Bay. However, this was a mistake as the ship misidentified the fleet for the Third Fleet, which was also on patrol. On May 27, while the Sado Maru was in charge of the central line,[8] the Baltic Fleet was discovered by Shinano Maru which was in charge of the right trunk line. The Sado Maru discovered the sinking Admiral Nakhimov during the battle as the already had her crew off the ship and the Shiranui conducting rescue operations. Kamaya brought the Sado Maru alongside the Shiranui to transfer the Russian naval officers and soldiers and dispatched Captain Sukejiro Inuzuka to capture the Admiral Nakhimov. Her captain and several officers were staying on the Admiral Nakhimov and Inuzuka recommends leaving the ship in its sinking state. During this time, the Vladimir Monomakh and the Gromky appeared and both were bombarded with the Shiranui pursuing the ships. The Vladimir Monomakh surrendered and Kamaya tried to accommodate the ships crew aboard the Sado Maru but the capacity reached its maximum point as the ship already contained 523 sailors from the Admiral Nakhimov. Kamaya then summoned the Manshū, and the 406-man crew of the Vladimir Monomakh were rescued.[9]

After the Battle of Tsushima, he became captain of the coastal defense ship Okinoshima which was a former Russian coast defense ship captured during the Battle of Tsushima, and participated in the Japanese invasion of Sakhalin.

Later career

After the war, Kamaya became the military attaché to Chinese Legation in December and departed from the Imperial Japanese Navy General Staff in June 1906. He later became the captain of the Nisshin on October and the Izumo in August 1907. Beginning in February 1908, Kamaya became the Chief of Staff of the Ōminato Guard District, Captain of the Hizen on July and commander of the Sasebo Naval District on December. He then returned to the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal to become the torpedo commander in December 1909 before his promotion to Rear-Admiral and Chief of Staff of the Lushun Naval District in December 1910. He also served as the Chief of Staff of the Yokosuka Naval District and later given command of the Sasebo Reserve Fleet in July 1912. He then became the Fleet Commander of the Sasebo Naval District in April 1913 and the commander of the Mako Guard District in December 1913. He finally received his promotion to Vice Admiral in 1913 before being placed in the reserves and retired on December 1, 1915.[10] After his military career, he dedicated his future ventures to become a banker and later, became the Chairman of the Asahi Shinkin Bank.[11] After Kamaya's death on January 19, 1939, Kamiizumi Tokuya attended his funeral.[12]

Court Ranks

Awards

- The Commemorative Medal for the Imperial Constitution Promulgation (November 29, 1889)[19]

- Order of the Sacred Treasure, 6th Class (November 18, 1895)

- Order of the Golden Kite, 5th Class (November 18, 1895)[20]

- Meiji 278 -- Military Medal of Honor (November 18, 1895)[21]

- Order of the Rising Sun, 5th Class (June 26, 1896)[22]

- Order of the Sacred Treasure, 4th Class (May 16, 1903)[23]

- Commemorative Medal of the Crown Prince's Visit to Korea (April 18, 1909)[24]

- Order of the Sacred Treasure, 2nd Class (May 16, 1914)[25]

- Taishō Commemorative Medal (November 10, 1915)[26]

References

- 『海軍兵学校沿革』では少尉補

- Promotion and conferment of medals for two people under Tadamichi Kamaya, Captain of the Navy, Senior Seventh Rank, Sixth Class, Fifth Class (海軍大尉正七位勲六等功五級釜谷忠道以下二名勲位進級及勲章加授ノ件)

- Matsuno 1980, p. 349-350.

- Matsuno 1980, p. 56.

- "No. 98 List of casualties of warship Hatsuse at the time of disaster outside Lushun Port on May 15, 1902" (「第98号 明治37年5月15日旅順港外遭難の際に於る軍艦初瀬戦死者人名表」)

- Itō 1956, p. 174-175.

- 『懐旧録』釜屋忠道「龍田の遭難」

- "日本海海戦当日朝敵艦発見時に於る哨艦配備図". Japan Center for Asian Historical Records. Ref. C05110095900.

- "第2編 日本海海戦/第3章 5月28日に於る戦闘". Japan Center for Asian Historical Records. Ref. C05110084600., p. 25-27

- "Official Gazette" No. 1001, December 2, 1914.

- "米沢信用金庫" (in Japanese). Retrieved March 16, 2012.

- Matsuno 1980, p. 348.

- "Official Gazette" No. 2541 "Appointment and Appointment" December 17, 1891.

- "Official Gazette" No. 4903 "Appointment and Appointment" November 2, 1899.

- "Official Gazette" No. 6422 "Appointment and Appointment" November 25, 1904.

- "Official Gazette" No. 8243 "Appointment and Appointment" December 12, 1910.

- "Official Gazette" No. 731 "Appointment and Appointment" January 12, 1915.

- "Official Gazette" No. 1024 "Appointment and Appointment" December 29, 1915.

- "Official Gazette" Extra "Appointment and Appointment" December 29, 1889.

- "Official Gazette" No. 3727 "Appointment and Appointment" November 29, 1895.

- "Official Gazette" No. 3858, Appendix "Appointment" May 12, 1896.

- "Official Gazette" No. 3899 "Appointment and Appointment" June 29, 1896.

- "Official Gazette" No. 5960 "Appointment and Appointment" May 18, 1903.

- "Official Gazette" No. 7771 "Appointment and Appointment" May 24, 1909.

- "Official Gazette" No. 539 "Appointment and Appointment" May 18, 1914.

- "Official Gazette" No. 1310, appendix "Appointment" December 13, 1916.

Bibliography

- Itō, Masanori (1956). 大海軍を想う. Bungeishunju Shinsha.

- Naval History Preservation Society, ed. (1995). 日本海軍史. Vol. 9. Daiichi Hoki Publishing.

- Kojima, Jō (1994). 日露戦争. Bunshun Bunko. ISBN 4-16-714147-7.

- Kojima, Jō (1994). 日露戦争. Bunshun Bunko. ISBN 4-16-714151-5.

- Kojima, Jō (1994). 日露戦争. Bunshun Bunko. ISBN 4-16-714152-3.

- Suikokai [in Japanese] (1985). 回想の日本海軍. Hara Shobo. ISBN 4-562-01672-8.

- Misao Toyama, ed. (1981). 陸海軍将官人事総覧 海軍篇. Fuyo Shobo Publishing. ISBN 4-8295-0003-4.

- Matsuno, Yoshitora (1980). 遠い潮騒 米沢海軍の系譜と追憶. Yonezawa Navy Military Officials Association.

- 海軍兵学校沿革. Meiji 100th Year History. Vol. 74. Hara Shobo.

- 有終会編. 懐旧録. Vol. 2.