Taito (kanji)

Taito, daito, or otodo (𱁬/![]() ) is a kokuji ("kanji character invented in Japan") written with 84 strokes, and thus the most graphically complex CJK character—collectively referring to Chinese characters and derivatives used in the written Chinese, Japanese, and Korean languages. This rare and complex character graphically places the 36-stroke tai 䨺 (with tripled 雲 "cloud"), meaning "cloudy", above the 48-stroke tō 龘 (tripled 龍 "dragon") "appearance of a dragon in flight". The second most complicated CJK character is the 58-stroke Chinese biáng (𰻞/

) is a kokuji ("kanji character invented in Japan") written with 84 strokes, and thus the most graphically complex CJK character—collectively referring to Chinese characters and derivatives used in the written Chinese, Japanese, and Korean languages. This rare and complex character graphically places the 36-stroke tai 䨺 (with tripled 雲 "cloud"), meaning "cloudy", above the 48-stroke tō 龘 (tripled 龍 "dragon") "appearance of a dragon in flight". The second most complicated CJK character is the 58-stroke Chinese biáng (𰻞/![]() ), which was invented for Biangbiang noodles "a Shaanxi-style Chinese noodle".

), which was invented for Biangbiang noodles "a Shaanxi-style Chinese noodle".

Composition

The Chinese character components for taito are both compound ideographs created by reduplicating a common character, namely the 12-stroke Japanese kumo or Chinese yún 雲 "cloud" (with the "rain radical" 雨 and un or yún 云 phonetic), and the 16-stroke "dragon radical" Japanese ryū or Chinese lóng 龍. The 雲 "cloud" character is tripled into 36-stroke tai or duì 䨺 "cloudy" and quadrupled into 48-stroke dō or nóng 𩇔 "widely cloudy"; the 龍 "dragon" character is interchangeably doubled or tripled into 32- or 48-stroke tō or dá 龖 or 龘 "appearance of a dragon in flight" and quadrupled into 64-stroke tō or zhé 𪚥 "chattering; be garrulous".

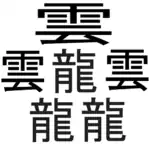

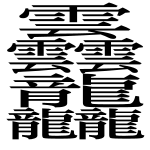

The taito, daito, or otodo character has two graphic variants (see images), the principal difference being the placement of the first dragon character. In version 1 (read either daito or otodo), the first dragon is written between the second and third cloud characters, starting at the 25th stroke. In version 2 (read taito), the first dragon is written after the third cloud character, starting at the 37th stroke.

These triple dragon 龘 and triple cloud 䨺 logographs typify a type of CJK character formation. Several scholars have explained Chinese writing with a chemical bond analogy of Chinese character radicals as "atoms" that join together to form characters as "molecules". Some illustrations of "atomic structures" in Chinese characters are

- nǚ 女 "woman", nuán 奻 "quarrel" , jiāo 㚣 (=姣) "beautiful", and jiān 姦 "adultery; illicit sexual relations"

- mù 木 "tree", lín 林 "woods; grove", and sēn 森 "forest"

- ěr 耳 "ear", dié 聑 "settle a price", and niè 聶 (=囁) "mumble; whisper" (or Niè 聶, a surname)

- tián 田 "field", jiāng 畕 (=畺) "dykes between fields", and léi 畾 "spaces between fields"

The British historian of Chinese science Joseph Needham (1954: 31) explained, "To the natural scientist approaching the study of Chinese, a helpful analogy is possible with chemical molecules and atoms—the characters may be considered roughly as so many molecules composed of the various permutations and combinations of a set of 214 atoms" (i.e., the 214 Kangxi radicals). Lexicographer Jack Halpern (1981: 73) similarly said, "The essence of the scheme is that the formation of Chinese characters can be likened to the way atoms combine to form the more complex molecules of compounds." The American linguist Michael Carr (1986: 79) examined the best-case example of semantic "crystal characters" invented by repeating a radical, much like atoms forming crystal patterns—in the sense of rì 日 the "sun radical" in chāng 昌 "sunlight; prosperous", xuān 昍 "bright", and jīng 晶 "bright; crystal". Carr (1986: 82-3) further distinguished "natural" crystal characters that occur in standard, written Chinese (citing the above example of dá 龖 "appearance of a dragon in flight" from the 龍 "dragon radical") versus "synthetic" or "artificial" ones that are restricted to Chinese dictionaries (dá 龘 "appearance of a dragon in flight" and zhé 𪚥 "chatter"), which "are graphic ghosts from previous dictionaries, and unattested in actual usage."

Usage

Some specialized Japanese dictionaries include the taito, daito, or otodo characters. Ono and Fujita's (1977) dictionary of Japanese names with difficult readings enters variant 1 pronounced daito or otodo. Ōsuga's (1964) surname dictionary and Sugaware and Hida's (1990) kokuji dictionary include graphic variant 2 pronounced taito.

This 84-stroke dictionary ghost word became a real Japanese name in 2000 when a ramen shop near the Kita-Matsudo Station in Chiba Prefecture was named using character variant 1 pronounced Otodo (Sasahara 2001).

Chinese dictionaries

Unabridged dictionaries of Chinese characters do not include either Japanese 84-stroke taito variant. Both Morohashi Tetsuji's Chinese-Japanese Dai Kan-Wa jiten, which has 49,964 head entries for characters, and the Chinese Hanyu Da Zidian (1989), which has 54,678, list the three most graphically complex characters as the 52-stroke Japanese hō or bō and Chinese bèng 䨻 "sound of thunder" (with quadruple 雷 "thunder"; 1960: 12693, 1989 6: 4085), 64-stroke tetsu or techi and zhé 𪚥 "chatter; be garrulous" (with quadruple 龍 "dragon"; 13747, 7: 4806), and 64-stroke sei and zhéng 𠔻 "meaning unknown" (with quadruple 興 "rise"; 9816, 1: 254)—the first occurrence of the ghost word 𠔻 was in Sima Guang's (1066) Leipian dictionary, which gives the pronunciation gloss zhèng 政 but no semantic gloss.

Encoding

Some extensive encoding systems for Japanese kanji (preceding Unicode) include taito variant character 2. The superseded Mojikyo font, which comprised 142,228 rare and obsolete characters, included it as number [066147]. The deprecated BTRON Business computer architecture TRON project (TRON stands for "The Real-time Operating system Nucleus") also included taito [3-7D6B], and it was included in the font under development by the Tokyo University of Foreign Studies's Jitī shotai GT書体 project.

In December 2015 it was included in document IRGN2107 as one of 1,640 characters submitted to the Ideographic Rapporteur Group for encoding in Unicode (character source reference UTC-02960).[1] The character was provisionally included in "IRG Working Set 2015", which are candidates for inclusion in a future CJK Unified Ideographs extension.[2]

This character was added to Unicode version 13.0 in March 2020. The character is located at U+3106C (𱁬) in the CJK Unified Ideographs Extension G block in the newly-allocated Tertiary Ideographic Plane.[3]

References

- "IRGN2107R: UK Submission for IRG Working Set 2015". Ideographic Rapporteur Group. 12 December 2015.

- "IRGN2133: CJK Working Set 2015 v1.1". Ideographic Rapporteur Group. 23 January 2016.

- "CJK Unified Ideographs Extension G" (PDF). Unicode. 11 March 2020. p. 454.

- Carr, Michael (1986), "Semantic Crystals in Chinese Characters", Review of Liberal Arts (人文研究), 71:79-97.

- Halpern, Jack (1981), "The Sound of One Land" (part 9), "A Method in the Madness" PHP, December 1981: 73–80.

- Hanyu da zidian weiyuanhui 漢語大字典委員會, eds. (1989), Hanyu Da Zidian 漢語大字典 [Comprehensive Chinese Character Dictionary], 8 vols., Hubei cishu chubanshe and Sichuan cishu chubanshe. (in Chinese)

- Morohashi Tetsuji (1960), Dai Kan-Wa jiten 大漢和辞典 [Comprehensive Chinese-Japanese Character Dictionary], 13 vols.,Taishukan. (in Japanese)

- Needham, Joseph (1954), Science and Civilisation in China, Introductory Orientations, vol. 1, Cambridge University Press.

- Ōno, Shirō 大野史朗 and Fujita, Yutaka 藤田豊 (1977), Nandoku seishi jiten 難読姓氏辞典 [Dictionary of Names with Difficult Readings], Tōkyōdō Shuppan. (in Japanese)

- Ōsuga, Tsuruhiko 大須賀鶴彦 (1964), Jitsuyō seishi jiten 実用姓氏辞典 Practical Dictionary of Surnames, Mēringu. (in Japanese)

- Sasahara Hiroyuki 笹原宏之 (2011), 漢字の現在 第82回 幽霊文字からキョンシー文字へ? [From ghost character to vampire character?], 三省堂辞書サイト Sanseido Word-Wise Web, 8 February 2011. (in Japanese)

- Sugawara, Yoshizō 菅原義三 and Hida, Yoshifumi 飛田良文 (1990), Kokuji no jiten 国字の字典 [Dictionary of Kokuji], Tōkyōdō. (in Japanese)

External links

Media related to Taito (kanji) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Taito (kanji) at Wikimedia Commons The dictionary definition of 𱁬 at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of 𱁬 at Wiktionary- character 66147, Mojikyo entry for variant 2

- character GT-57123 or u2ff1-u4a3a-u9f98, GT entry for variant 2, GlyphWiki