Emperor Taizong of Song

Zhao Jiong (20 November 939 – 8 May 997), known as Zhao Guangyi from 960 to 977 and Zhao Kuangyi before 960, also known by his temple name as the Emperor Taizong of Song, was the second emperor of the Song dynasty of China. He reigned from 976 to his death in 997. He was a younger brother of his predecessor Emperor Taizu, and the father of his successor Emperor Zhenzong.

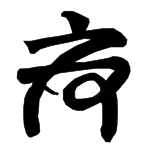

| Emperor Taizong of Song 宋太宗 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Palace portrait on a hanging scroll, kept in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan | |||||||||||||

| Emperor of the Song dynasty | |||||||||||||

| Reign | 15 November 976 – 8 May 997 | ||||||||||||

| Coronation | 15 November 976 | ||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Emperor Taizu | ||||||||||||

| Successor | Emperor Zhenzong | ||||||||||||

| Born | Zhao Kuangyi (939–960) Zhao Guangyi (960–977) Zhao Jiong (977–997) 20 November 939[1][2] Xunyi County, Kaifeng Prefecture, Later Jin dynasty (present-day Kaifeng, Henan, China)[1] | ||||||||||||

| Died | 8 May 997 (aged 57)[2][3] Bianjing, Northern Song dynasty (present-day Kaifeng, Henan, China) | ||||||||||||

| Burial | Yongxi Mausoleum (永熙陵, in present-day Gongyi, Henan) | ||||||||||||

| Consorts | Empress Shude Empress Yide (died 975) Empress Mingde (m. 978–997) Empress Yuande (died 977) | ||||||||||||

| Issue | See § Family | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| House | Zhao | ||||||||||||

| Dynasty | Song (Northern Song) | ||||||||||||

| Father | Zhao Hongyin | ||||||||||||

| Mother | Empress Dowager Zhaoxian | ||||||||||||

| Signature |  | ||||||||||||

| Emperor Taizong of Song | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 宋太宗 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | "Great Ancestor of the Song" | ||||||

| |||||||

| Zhao Kuangyi | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 趙匡義 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 赵匡义 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Zhao Guangyi | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 趙光義 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 赵光义 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Zhao Jiong | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 趙炅 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 赵炅 | ||||||

| |||||||

Why Emperor Taizong succeeded his brother rather than Emperor Taizu's grown sons (Zhao Dezhao and Zhao Defang, who both died in their twenties during his reign) is not entirely understood by later historians. According to official history, his succession was confirmed by Emperor Taizu on their mother Empress Dowager Du's deathbed as a result of her instruction. A popular story dating back from at least the 11th century suggests that Emperor Taizong murdered his brother in the dim candlelight when the sound of an axe was allegedly heard. Whatever the truth, Zhao Guangyi had been prefect of the Song capital Kaifeng since 961 where he gradually consolidated power. He was the only living prince during Emperor Taizu's reign (as Prince of Jin) and placed above all grand councilors in regular audiences.

In the first three years of his reign, he intimidated the Qingyuan warlord Chen Hongjin and Wuyue king Qian Chu into submission and easily conquered the Northern Han, thus reunifying China proper for the first time in 72 years. However, subsequent irredentist wars to conquer former Tang dynasty territories from the Liao dynasty in the north and the Early Lê dynasty in the southeast proved disastrous: after the failures in the Battle of Gaoliang River and the Battle of Bạch Đằng, the Sixteen Prefectures and Northern Vietnam (at least in their entirety) would remain beyond Han control until the Ming dynasty in the 14th century.

Emperor Taizong is remembered as a hardworking and diligent emperor. He paid great attention to the welfare of his people and made the Song Empire more prosperous. He adopted the centralization policies of the Later Zhou, which include increasing agricultural production, broadening the imperial examination system, compiling encyclopaedias, expanding the civil service and further limiting the power of jiedushis.

All subsequent emperors of the Northern Song were his descendants, as well as the first emperor of the Southern Song. However, from Emperor Xiaozong onwards, subsequent emperors were descendants of his brother, Emperor Taizu. This largely stemmed from the Jingkang Incident, whereby most of Emperor Taizong's descendants were abducted by the Jin dynasty, forcing Emperor Gaozong to seek a successor among Taizu's descendants, as Gaozong's only son had died young.

Early life

Emperor Taizong was born in 939 in Kaifeng. After his brother Emperor Taizu took the throne, he was appointed prefect of Kaifeng. He was the Prince of Jin in his brother's reign.

Succeeding the throne and suspected fratricide

Emperor Taizong succeeded the throne in 976 after the death of his elder brother, Emperor Taizu, who was 49 and had no recorded illness. It is rather unusual in Chinese history for a brother rather than the son to succeed the throne, so the event fueled popular belief that foul play was involved.

According to official history, Empress Dowager Du before her death in 961 asked the 34-year-old Emperor Taizu to promise that his brother will succeed him so as to ensure the continuation of the Song dynasty. She reportedly asked Emperor Taizu, "Do you know why you came to power? It was because Later Zhou had a seven-year-old emperor!" The so-called "Golden Shelf Promise" (金匱誓書) was also allegedly recorded and sealed, by secretary Zhao Pu and reopened after Emperor Taizong's succession to prove the latter's legitimacy.

Emperor Taizu's eldest son, Zhao Dezhao, was already 25 years old in 976, certainly old enough to handle an emperor's duties. Also suspicious is that Zhao Pu, banished in 973 by Emperor Taizu for allegations of corruption, returned to the capital in 976 and was made the chancellor in 977.

Wen Ying, a Buddhist monk who lived in the era of Emperor Taizong's grandson, Emperor Renzong, wrote an account about the last night of Emperor Taizu.[4] According to this account, he was dining and drinking with Emperor Taizong, then still the "Prince of Kaifeng", beside some candles. Palace eunuchs and maids standing in a distance saw that Emperor Taizong's shadow on the window moved a lot and appeared antsy. It was getting late and several inches of snow have fallen on the inside of the hall. Then they heard an axe chopping the snow, with Emperor Taizu saying, "Do it right! Do it right!" Soon enough Emperor Taizu was heard snoring. Several hours later, he was pronounced dead by his brother, who spent the night in his palace. This legend has been referred to as "sound of the axe in the shadow of the flickering candle" (斧声烛影) and proved to be popular to this day.[5]

Modern historians were unable to find any concrete evidence suggesting murder; however they generally accept that the "Golden Shelf Promise" as fraud fabricated by Emperor Taizong and Zhao Pu.

Also worth mentioning is the suicide of Zhao Dezhao, Emperor Taizu's eldest son, three years after his father's death. During Emperor Taizong's first campaign against the Khitan-led Liao dynasty, Zhao Dezhao was leading an army when rumours spread that Emperor Taizong had disappeared, and that Zhao Dezhao should be the new emperor.[6] Upon hearing that, Emperor Taizong did not award the troops when they returned. When Zhao Dezhao asked him, Emperor Taizong barked back, "You do that when you become the new emperor!" According to this account, Zhao Dezhao immediately went to his palace and killed himself and when Taizong heard about the suicide, he was very sad and hugged the corpse crying.

Emperor Taizu's second son, Zhao Defang, died in 981 from an unidentified illness. Just 22, he was unusually young. Emperor Taizong was very sad and visited Defang's grave and cancelled meetings for 5 days. During the same year, Emperors Taizong and Taizu's younger brother, Zhao Tingmei (previously known as Zhao Guangmei and Zhao Kuangmei), was also stripped of his title "Prince of Qi" and sent to the Western Capital. He died three years later. Moreover, when Emperor Taizu's widow Empress Song died, her body was not buried with her late husband and not given the recognition according to tradition.[7]

After Emperor Taizong's ascension to the throne, there were persistent doubts as to the legitimacy of the succession, and a popular prophecy arose that Taizu's descendants will rightfully return to the throne one day (太祖之後當再有天下). This prophecy proved true when Taizu's seventh-generation descendant Xiaozong became emperor after the capture of most of Taizong's line by the Jurchens during the Jingkang incident and Gaozong, the first emperor of the Southern Song dynasty, whose own son Zhao Fu died young, lacked an heir.

Military campaigns

Conquering Northern Han

Emperor Taizong personally led the campaign against Northern Han in 979 and ordered the flooding of enemy cities by releasing the Fen River. The Northern Han ruler Liu Jiyuan was forced to surrender, thus ending all the kingdoms and dynasties in the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period.

First campaign against the Liao dynasty

Having conquered Northern Han in 979, Emperor Taizong took advantage of the momentum and launched another military campaign against the Khitan-led Liao dynasty. In May 979, Emperor Taizong embarked on his campaign from Taiyuan and took Zhuo and Yi Prefectures easily. He besieged Yanjing (present-day Beijing) after the success. However, the siege failed when the Liao defending general Yelü Xuegu defended the fortress firmly.

Concurrently, Liao reinforcements led by Yelü Xiuge arrived from the Gaoliang River region, west of Yanjing. Emperor Taizong ordered his army to attack the reinforcements. Initially, he received reports that the Liao army was suffering heavy casualties. He ordered a full assault on the Liao army as he thought that the whole battle was under his control. Just then, Yelü Xiuge and Yelü Xiezhen's armies attacked from two sides. Yelü Xiuge concentrated on attacking Emperor Taizong's main camp. Emperor Taizong was shocked and evacuated from the battlefield. During the evacuation, the Song army was divided and obliterated by the Liao cavalry.

Amidst the onslaught, Emperor Taizong fled towards Yi Prefecture and arrived there safely with his generals protecting him. He sustained an injury from an arrow and was unable to ride on his horse and had to travel by carriage back to Ding Prefecture. Emperor Taizong ordered a retreat after that. The Song army was without a commander as Emperor Taizong was separated from his troops. The troops suggested that Emperor Taizu's eldest son, Zhao Dezhao (Emperor Taizong's nephew), be the new emperor. Emperor Taizong's suspicions were raised when he heard that and eventually he ordered Zhao Dezhao to commit suicide.

The Battle of Gaoliang River was significant as it was one of the major contributing factors to the Song dynasty's decision to adopt a defensive stance. The early Song army suffered its first major defeat in battle. Meanwhile, Emperor Taizong was also troubled by the possibility that Zhao Dezhao would launch a coup. After the battle, Emperor Taizong personally inspected and focused more on the development and strengthening of his military forces. He ignored his subjects' advice and regarded state affairs as of lower importance. He also limited the power and control that the imperial family and military officers had over the army.

Second campaign against the Liao dynasty

After the death of Emperor Jingzong of Liao in 982, the 12-year-old Emperor Shengzong of Liao ascended to the throne of the Liao Dynasty. As Emperor Shengzong was too young to rule the kingdom, Empress Dowager Xiao became the regent. Emperor Taizong decided to launch the second campaign against Liao in 986, following the advice of his subjects.

During this time, Zhao Yuanzuo, Taizong's oldest son became insane after the death of his uncle, Zhao Tingmei, and that he was not invited to the Double Night Daylight Feast which ultimately caused Yuanzuo to burn down the palace.[8] As a result, Taizong, under the pressure of his censors demoted Yuanzuo to commoner status and exiled him.[8] This, was changed when 100 officials rejected Yuanzuo's exile and pressured Taizong to let Yuanzuo remain in the palace.[8] Three officials who had responsibility for Yuanzuo asked to be punished by Taizong in which Taizong said "This son, even I have been unable to reform through my teaching. How could you guide him?" in response.[8]

In 983, the practice of officials tutoring imperial princes began under his reign.[8] One notable case was Emperor Taizong's son Zhao Yuanjie and his tutor Yao Tan (935–1003) in which Yao constantly berated the young prince for being idle and lazy causing resentment from the prince.[9] Yao attempted to complain to Taizong who said "Yuanjie is literate and enjoys learning; that should be sufficient to make him a worthy prince. If when young he is immoderate, then it is necessary to have entreaties to rein in his ridicule. But if you slander him without good reason, how is that going to help him?"[9] However, Yuanjie under peer pressure from his friends feigned illness and began neglecting his duties. Concerned, Taizong checked the Prince's progress daily.[9] He summoned Yuanjie's wet nurse after the Prince still was "ill" for a month with the wet nurse stating "The Prince is basically not sick; it's just that with Yao Tan checking up on him, he can seldom follow his inclinations, and thus has become sick."[9] This enraged Emperor Taizong ordering her to be caned.[9]

Emperor Taizong remained in Bianjing and directed the war there without personally entering the battlefield. He split the army into three sections – East, Central and West. The East Army was led by Cao Bin, the Central Army by Tian Zhongjin and the West Army by Pan Mei and Yang Ye. All the three armies would attack Yanjing from three sides and capture it. The campaign was termed as the Yongxi Northern Campaign as it took place in the third year of the Yongxi era of Emperor Taizong's reign.

The three armies scored some victories initially but they became more divided later as they acted individually without cooperation. Cao Bin took the risk by attacking without the support of the other two armies. He succeeded in taking Zhuo Prefecture but the lack of food supplies forced him to retreat. As there was miscommunication between the three armies, the East Army attacked Zhuo Prefecture again. However, this time, Empress Dowager Xiao and Yelü Xiuge each led an army to support Zhuo Prefecture. The East Army was inflicted with a crushing defeat and almost completely destroyed.

Emperor Taizong was aware that the failure of the East Army would affect the entire campaign and he ordered a retreat. He ordered the East Army to return, the Central Army to guard Ding Prefecture and the West Army to guard four prefectures near the border. Following the defeat of the East Army, the Liao army led by Yelü Xiezhen attacked them as they retreated. The West Army led by Pan Mei met Yelü Xiezhen's army at Dai Prefecture and faced another defeat at the hands of the Liao army. The two commanders of the West Army started to argue about retreating. Yang Ye proposed that they should retreat since the East and Central Armies had already lost the advantage following their defeats. However, the other generals on Pan Mei's side began to doubt Yang's loyalty to Song as Yang Ye used to serve Northern Han. Yang Ye led an army to face the Liao troops but they were trapped and Yang committed suicide eventually. Pan Mei was supposed to arrive with reinforcements to support Yang but he failed to do so.

Emperor Taizong ordered another retreat following the Song armies' defeats by Yelü Xiuge and Yelü Xiezhen. The failure of the second campaign was attributed to the miscommunication between the three armies and their failures to operate together. Besides, Emperor Taizong had also restricted the decisions of his generals as he had arbitrarily planned the whole campaign against Liao and his generals had to adhere to his orders strictly. These failures led to internal rebellions which were crushed swiftly.

In 988, the Liao armies led by Empress Dowager Xiao attacked the Song border again. Emperor Taizong did not order a counter-attack and merely instructed the troops to defend firmly.

Later reign after 988

Emperor Taizong felt that he could not surpass his brother (Emperor Taizu) in terms of military conquests and achievements and decided to focus more on developing his dynasty internally and establish his legacy. He implemented a series of economic and literary reforms which were better than his brother's. He also initiated many construction projects and inducted new systems absent in Emperor Taizu's reign.

Emperor Taizong died in 997 after reigning for 21 years at the age of 57. He was succeeded by his third son, who became Emperor Zhenzong.

Family

Consorts and Issue:

- Empress Shude, of the Yin clan (淑德皇后 尹氏)

- unnamed daughter

- Empress Yide, of the Fu clan (懿德皇后 符氏; 941–975)

- Empress Mingde, of the Li clan (明德皇后 李氏; 960–1004)

- Unnamed son

- Empress Yuande, of the Li clan (元德皇后 李氏; 943–977)

- Zhao Yuanzuo, Prince Hangongxian (漢恭憲王 趙元佐; 965–1027), first son

- Zhao Heng, Zhenzong (真宗 趙恆; 968–1022), third son

- Unnamed daughter

- Unnamed daughter

- Noble Consort Sun, of the Sun clan (貴妃孫氏)

- Worthy Consort, of the Gao clan (贤妃 高氏)

- Virtuous Consort, of the Zhu clan (德妃 朱氏, d. 1035), personal name Chonghui (冲惠)

- Able Consort, of the Shao clan (賢妃 邵氏, d. 1016), personal name Zhaoming (昭明)

- Noble Consort, of the Zang clan (貴妃 臧氏)

- Zhao Yuancheng, Prince Chugonghui (楚恭惠王 趙元偁; 981–1014), seventh son

- Princess Hejing (和靖帝姬; d. 1033), fourth daughter

- Married Chai Zongqing (柴宗慶; 982–1044) in 1002

- Princess Ciming (慈明帝姬; d. 1024), personal name Qingyu (清裕), sixth daughter

- Noble Consort, of the Fang clan (貴妃 方氏; d. 1022)

- Princess Xianmu (獻穆帝姬; 988–1051), ninth daughter

- Married Li Zunxu (李遵勗; 988–1038) in 1008

- Princess Xianmu (獻穆帝姬; 988–1051), ninth daughter

- Virtuous Consort, of the Wang clan (德妃 王氏)

- Zhao Yuanyan, Prince Zhougongsu (週恭肅王 趙元儼; 986–1044), eighth son

- Shuyi, of the Li clan (淑儀 李氏)

- Shuyi, of the Wu clan (淑儀吳氏)

- Unknown

- Zhao Yuanxi, Crown Prince Zhaocheng (昭成皇太子 趙元僖; 966–992), second son

- Zhao Yuanfen, Prince Shanggongjing (商恭靖王 趙元份; 969–1005), fourth son

- Zhao Yuanjie, Prince Yuewenhui (越文惠王 趙元杰; 972–1003), fifth son

- Zhao Yuanwo, Prince Zhengongyi (鎮恭懿王 趙元偓; 977–1018), sixth son

- Zhao Yuanyi, Prince Chong (崇王 趙元億), ninth son

- Princess Heqing (和慶帝姬)

- Princess Yinghui (英惠帝姬; d. 990), second daughter

- Married Wu Yuanyi (吳元扆; 962–1011) in 984

- Princess Chunmei (純美帝姬; d. 983), third daughter

- Princess Yishun (懿順帝姬; d. 1004), fifth daughter

- Married Wang Yiyong (王貽永; 986–1056) in 1003

Ancestry

| Zhao Tiao | |||||||||||||||||||

| Zhao Ting | |||||||||||||||||||

| Empress Wenyi | |||||||||||||||||||

| Zhao Jing (872–933) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Sang Shifu | |||||||||||||||||||

| Empress Huiming | |||||||||||||||||||

| Zhao Hongyin (899–956) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Liu Yan | |||||||||||||||||||

| Liu Chang | |||||||||||||||||||

| Empress Jianmu | |||||||||||||||||||

| Emperor Taizong of Song (939–997) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Du Yun | |||||||||||||||||||

| Du Wan | |||||||||||||||||||

| Lady Liu | |||||||||||||||||||

| Du Shuang | |||||||||||||||||||

| Lady Zhao | |||||||||||||||||||

| Empress Dowager Zhaoxian (902–961) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Lady Fan | |||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- Song Shi, vol. 4

- (in Chinese) Academia Sinica Chinese-Western Calendar Converter

- Song Shi, vol. 5

- (in Chinese) Wen Ying. (Northern Song Dynasty). Xiang Shan Ye Lu (湘山野錄), Addendum.

- John W. Chaffee (1999). Branches of Heaven: A History of the Imperial Clan of Sung China. Harvard Univ Asia Center. pp. 27–. ISBN 978-0-674-08049-2.

- (in Chinese) Sima Guang. (Northern Song dynasty). Sushui Jiwen (涑水記聞), Volume 2.

- (in Chinese) Toqto'a. (Yuan dynasty). History of Song, Volume 293.

- John W. Chaffee (1999). Branches of Heaven: A History of the Imperial Clan of Sung China. Harvard Univ Asia Center. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-674-08049-2.

- John W. Chaffee (1999). Branches of Heaven: A History of the Imperial Clan of Sung China. Harvard Univ Asia Center. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-674-08049-2.

Sources

- (in Chinese) Toqto'a; et al. (1345). Song Shi (宋史) [History of Song].

- Chaffee, John W. (1999). Branches of Heaven: History of the Imperial Clan of Sung China. Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 0674080491.

- Lau Nap-yin; Huang K’uan-chung (2009). "Founding and Consolidation of the Sung Dynasty under T'ai-tsu (960–976), T'ai-tsung (976–997), and Chen-tsung (997–1022)". In Twitchett, Dennis; Smith, Paul Jakov (eds.). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 5: The Sung Dynasty and its Precursors, 907–1279, Part 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 206–278. ISBN 978-0-521-81248-1.