Toke Atoll

Toke Atoll or Taka Atoll (Marshallese: Tōkā, [tˠʌɡæ][1]) is a small, uninhabited coral atoll in the Ratak Chain of the Marshall Islands. It is one of the smaller atolls in the Marshalls and located at 11°17′N 169°37′E. It is visited regularly by the residents of nearby Utirik Atoll.

.jpg.webp) Map of Toke Atoll | |

Toke Atoll | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | North Pacific |

| Coordinates | 11°17′N 169°37′E |

| Archipelago | Marshall Islands |

| Total islands | 6 |

| Major islands | 1 |

| Area | 36.18 sq mi (93.7 km2) |

| Highest elevation | 1 ft (0.3 m) |

| Administration | |

.jpg.webp)

Geography

The atoll is 160 kilometers (100 mi) north of Majuro Atoll, the capital of the Marshall Islands, and 10 kilometers (6.2 mi) southwest of Utirik Atoll. It comprises six islands with a combined land area of 0.57 square kilometers (0.22 sq mi) and a lagoon area of 93.1 square kilometers (35.96 sq mi).[2]

Physical features

The atoll is roughly triangular in shape, its length and width approximately 9 miles (14 kilometers). The highest point is 15 feet (4.6 meters) above sea level. The small land area is the second smallest in the Marshalls, besting only Bikar. Among its islets, only Toke, Eluk, and Lojrong are large enough to support permanent vegetation. The other sand islets have shown considerable shifting in size and location over the years. Ground water sampled from the midsection of Toke islet is brackish, with chloride levels of 440 to 840 ppm (compared to 19400 ppm for sea water) [3] With a moderately shallow lagoon and single, deep, narrow western passage through the reef, Toke and its neighbor Utirik are an intermediate atoll type between the shallow, perched lagoons of Bokak and Bikar, and the deep lagoons and many reef passages of the central Marshall atolls.[4]

Based on the results of drilling operations on Enewetak (Eniwetok) Atoll, in the nearby Ralik Chain of the Marshall Islands, Toke may include as much as 1,400 meters (4,600 ft) of reef material atop a basalt rock base. As most local coral growth stops at about 46 meters (150 ft) below the ocean surface, such a massive stony coral base suggests a gradual isostatic subsidence of the underlying extinct volcano,[4] which itself rises 3,000 meters (10,000 ft) from the surrounding ocean floor. Shallow water fossils taken from just above Enewetak's basalt base are dated to about 55 mya.[5]

Soils are ultimately based on storm-driven ridges of coral rubble, standing 0.61 to 1.22 meters (2 to 4 ft) high. Away from the shorelines, soils are primarily sandy.[6] A thick layer of humus with a phosphate hardpan lies under the Pisonia forests.[7]

Climate

Toke is moderately dry, with annual precipitation in the range of 1,500–1,800 millimeters (60–70 in). Air temperature is usually near 28 °C (82 °F). The prevailing trade winds are from the northeast.[8] Rainfall in the Marshalls is primarily influenced by the equatorial front, which expands seasonally to 11 degrees north. To the north of that zone, rainfall quickly falls off. A quarter degree further north of Toke, annual rainfall at Enewetak Atoll is 1,200 millimeters (49 in) per year.[9]

Vegetation

Facing the lagoon shore, about a quarter of Toke islet is planted in coconuts with a thick ground cover of Microsorum scolopendria. There is a small grove of Pisonia grandis, while the rest of the islet is covered with brushy woods of Heliotropium foertherianum, Portulaca oleracea, and Pandanus tectorius, fringed by Lepturus repens grasses, Laportea ruderalis shrubs, Boerhavia diffusa, B. tetrandra and other typical Marshallese species. There is also a tiny grove of Pisonia on Lojiron.[10][11][12]

Fauna

Toke supports a healthy coral reef,[13] with over 93 coral types identified.[14] Evidence of green sea turtle nesting has been found on the three largest islets, and hawksbill sea turtles have been seen along the outer reef. The lagoon is home to the rare giant clam Tridacna gigas, as well as smaller giant clam varieties. The number of specimens is lower than that seen at Bokak and Bikar, perhaps because of poaching by foreign fishermen.[15]

Nineteen bird species are presently known on Toke Atoll. These include the reef heron, the migratory pectoral sandpiper and accidental examples of the spotted sandpiper and skua, for which Toke is their only sighting in Marshall Islands. Others include the resident crested tern, sooty tern, brown noddy, black noddy, white tern, black-naped tern, and the migrant wedge-tailed shearwater, red-tailed tropicbird, red-footed booby, brown booby, great frigatebird, golden plover, bristle-thighed curlew, wandering tattler, and ruddy turnstone.[8]

History

Prehistory

Although humans migrated to the Marshall Islands about 2000 years ago,[16] there appear to be no traditional Marshallese artifacts present that would indicate any long-term settlement. The lack of potable water and tiny lot of arable land compared to nearby Utirik has discouraged settlement. The atoll is traditionally occupied for brief periods for seasonal harvesting of copra, fish, turtles, coconut crabs, and other resources.[17] Along with the other uninhabited northern Ratak atolls of Bikar and Bokak, Toke was traditionally the hereditary property of the Ratak atoll chain Iroji Lablab. The exploitation of resources was regulated by custom, and overseen by the Iroji.[18]

16th century

The first sighting recorded by Europeans of Toke Atoll was by the Spanish navigator Álvaro de Saavedra on 29 December 1527 commanding the carrack Florida, and sailing from Zihuatanejo in New Spain. Together with Utirik, Rongelap and Ailinginae atolls they were charted as Islas de los Reyes (Islands of the Three Wise Kings in Spanish) due to the proximity of Epiphany.[19][20]

19th century

A number of Western ships recorded landfall on or passage by Toke during the 1800s, but no attempt at settlement or establishment of food animals was noted, likely due to the convenience of the settlement on nearby Utirik.[21]

The Russian brig Rurik, Captain Otto von Kotzebue, visited in the summer, 1817 during a search for a north passage between western Russia and its North American territories.[22]

20th century to present

The German Empire annexed the Marshall Islands in 1885[23] and added to the protectorate of German New Guinea in 1906. Using the justification that uninhabited atolls were unclaimed, the Germans seized Toke as government property, despite the protests of the Iroji.[18]

In 1914, the Empire of Japan occupied the Marshall Islands, and transferred German government properties to their own, including Toke. Like the Germans before them, the Japanese colonial administration (the South Seas Mandate) did not attempt to exploit the atoll, and the Northern Radak Marshallese continued to hunt and fish unmolested.[18] Following the end of World War II, it came under the control of the United States as part of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands

While en route from the US to Asia in April 1953, LST 1138, later commissioned as USS Steuben County, dropped anchor at Toke to search for rumored Japanese WWII-era stragglers. The landing party found no signs of any current occupants.[24]

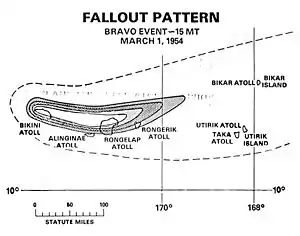

Toke Atoll was within the fallout zone of the Castle Bravo nuclear test. The degree of contamination in coconuts and coconut crabs is unknown, but levels are monitored on nearby Utirik.[25]

A 1981 study of fish and invertebrates within the lagoon found that the level of radio-nucleotides in muscle tissue was within the range found in fish products imported to the US and Japanese markets. The worldwide source of seafood-borne radio-nucleotides is a result of atmospheric nuclear testing since 1945, and therefore any residual activity from the 1950s Castle series of tests contributes only a small fraction of the contamination within the lagoon's sea life.[26]

See also

Footnotes

- Marshallese-English Dictionary - Place Name Index

- Marshall Islands Atoll Information

- Atoll Research Bulletin No. 419, page 40

- Atoll Research Bulletin No. 419, page 26

- Atoll Research Bulletin No. 260

- Atoll Research Bulletin No. 113, page 21

- Atoll Bulletin Research No. 330, page 52

- Atoll Research Bulletin No. 127

- Atoll Research Bulletin No. 30, page 2

- Atoll Research Bulletin No. 38, page 6

- Atoll Research Bulletin No. 39

- Atoll Research Bulletin No. 330

- Atoll Research Bulletin No. 419, page 1

- Atoll Research Bulletin No. 419, page 32

- Atoll Research Bulletin No. 419, page 45

- University of California, Berkeley

- Atoll Research Bulletin No. 38, page 20

- Atoll Research Bulletin No. 11

- Brand 1967, p. 121

- Sharp 1960, p. 18, 23

- Ships visiting the Marshall Islands

- The Romanzov Exploring Expedition

- Churchill, William (1920). "Germany's Lost Pacific Empire". Geographical Review. 10 (2): 84. JSTOR 207706.

- C.D. Pardee

- Atoll Research Bulletin No. 419, page 71

- Department of Health, Safety, and Security, DOE

References

- Aerial photos from EG&G (1978), and War Dept. (1944).

- Amerson, A.Binion Jr. (1969). "Atoll Research Bulletin No. 127, Ornithology of the Marshall and Gilbert Islands". Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. hdl:10088/6092.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - Arnow, Ted (1954). "Atoll Research Bulletin No. 30, The Hydrology of the Northern Marshall Islands". Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. hdl:10088/6094.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - Brand, Donald D. (1967). Friis, Herman R. (ed.). The Pacific basin; a history of its geographical exploration. New York: American Geographical Society. p. 121.

- Fosberg, F. Raymond (1955). "Atoll Research Bulletin No. 38, Northern Marshall Islands Expedition, 1951-1952, Narrative". Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. hdl:10088/4939.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - Fosberg, F. Raymond (1955-05-15). "Atoll Research Bulletin No. 39, Northern Marshall Islands Expedition, 1951-1952. Land biota: Vascular plants". Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. hdl:10088/4938.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - Fosberg, F. Raymond (1965). "Atoll Research Bulletin No. 113, Terrestrial Sediments and Soils of the Northern Marshall Islands". Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. p. 47. hdl:10088/4842.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - Fosberg, F. Raymond (1990). "Atoll Research Bulletin No. 330, A Review of the Natural History of the Marshall Islands". Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. hdl:10088/4933.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - Kirch, Patrick V. "Introduction to Pacific Islands Archaeology". Archaeological Research Facility, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. Retrieved 2010-06-04.

- "LST 1138 aka USS STEUBEN COUNTY, Years 1952-1955". C.D. Pardee. 2007-07-11. Archived from the original on 2009-10-26.

- Maragos, James E. (1994-08-30). "Atoll Research Bulletin No. 419, Description of reefs and corals for the 1988 Protected Area Survey of the Northern Marshall Islands". Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. hdl:10088/5870.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - "Northern Marshall Island Rad Survey: Radionuclide Concentrations in Fish and Clams and Estimated Doses via the Marine Pathway". Department of Health, Safety, and Security , DOE. 1981-08-18.

- Shar, Andrew (1960). Discovery of the Pacific Islands. Oxford University Press. pp. 18, 23. ISBN 978-0198215196.

- Spennemann, Dirk H.R. (2000). "Marshall Islands Atoll Information, Taka". Digital Micronesia. Albury NSW 2640, Australia: Institute of Land, Water and Society, Charles Sturt University. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Spennemann, Dirk H.R. (2000). "Ships visiting the Marshall Islands (until 1885), Taka Atoll". Digital Micronesia. Albury NSW 2640, Australia: Institute of Land, Water and Society, Charles Sturt University. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Tobin, J. E. (1952-09-01). "Atoll Research Bulletin No. 11, Land Tenure in the Marshall Islands". Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. hdl:10088/5075.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help)

External links

- Atoll Research Bulletin Archive Home Page

- Plants in the Marshall Islands, A Photo Essay

- Video: Glimpses of Taka Atoll

- Entry at Oceandots.com at the Wayback Machine (archived December 23, 2010)