Doolittle (album)

Doolittle is the second studio album by the American alternative rock band Pixies, released in April 1989 on 4AD. Doolittle was the Pixies' first international release, with Elektra Records as the album's distributor in the United States and PolyGram in Canada. Vocalist Black Francis' lyrics invoke biblical violence, surrealist imagery, and contain descriptions of torture and death, while the album is often praised for the quite/loud dynamic set up between Black's vocals, Joey Santiago's guitar and the rhythm section.

| Doolittle | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | April 17, 1989 | |||

| Recorded | October 31 – November 23, 1988 | |||

| Studio | Downtown Recorders (Boston) | |||

| Genre | Alternative rock | |||

| Length | 38:38 | |||

| Label | ||||

| Producer | Gil Norton | |||

| Pixies chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Doolittle | ||||

| ||||

"Doolittle" is considered one of the quintessential albums of the 1980s, and has sold consistently since its release. It reached number eight on the UK Albums Chart and was certified gold in 1995 and Platinum in 2018 by the Recording Industry Association of America. The Pixies released two singles from the album: "Here Comes Your Man" and "Monkey Gone to Heaven", both of which reached the Billboard Modern Rock Tracks chart in the US, while tracks such as "Debaser" and "Hey" remain fan and critical favourites. Numerous music publications rank it as one of the top albums of the 1980s, and it has been a heavy influence on for many alternative rock artists.

Background

Following their 1988 album Surfer Rosa, which was well received in England but not in the United States,[1] the band embarked on a European tour with fellow Bostonians Throwing Muses.[2] In July 1988, versions of the songs that would appear on Doolittle—including "Dead", "Hey", "Tame" and "There Goes My Gun"—were recorded during several sessions for John Peel's radio show in 1988, and "Hey" appeared on a free EP circulated with a 1988 edition of Sounds.[3]

In mid-1988 the Pixies began to record demo sessions while on breaks from touring. The band headed to the Boston recording studio Eden Sound, located in the basement of a hair salon. They recorded at the studio for a week, similar to the previous year's Purple Tape sessions. Black Francis, the group's frontman and principal songwriter, gave the demo tape and upcoming album the provisional title of Whore, later claiming that he meant it "in the more traditional sense ... the operatic, biblical sense, ... as in the great whore of Babylon".[4] After completing the demo tape, band manager Ken Goes suggested two producers for the album: Liverpudlian Gil Norton and American Ed Stasium. The band had previously worked with Norton while recording the single version of "Gigantic" in May 1988. Francis had no preference. Ivo Watts-Russell, head of the band's label 4AD, chose Norton to produce the next album.[5] Norton arrived in Boston in mid October 1988 and had Francis come over to his temporary apartment to review the album's demos. The two spent two days analyzing the song structures and arrangements. They spent a further two weeks in pre-production while Norton familiarize himself with the Pixies' sound.[6]

Recording and production

Recording sessions for the album began on October 31, 1988, at Downtown Recorders in Boston, Massachusetts, which was at the time a professional 24-track studio. 4AD allotted the Pixies a budget of $40,000 (approximately $98,976 today), excluding producer's fees. This was a modest sum for a 1980s major label album; however, it quadrupled the amount spent on the band's previous album, Surfer Rosa.[7] Along with Norton, two assistant recording engineers and two second assistants were assigned to the project.[8] The sessions lasted three weeks, concluding on November 23.[9]

Production and mixing began on November 28. The band relocated to Carriage House Studios, a residential studio in Stamford, Connecticut, to oversee production and record further tracks. Norton recruited Steven Haigler as mixing engineer, whom he had worked with at Fort Apache Studios.[10] During production, Haigler and Norton added layers of guitars and vocals to songs, including overdubbed guitars on "Debaser" and double tracked vocals on "Wave of Mutilation". During the recordings, Norton advised Francis to alter several songs; a noted example being "There Goes My Gun", which was originally intended as a much faster, Hüsker Dü-style song. At Norton's advice, Francis slowed down the tempo.[11]

Norton's suggestions were not always welcome, and several instances of advice to add verses and increase track length contributed to the Francis's building frustration. Once, he took Norton to a record store and handed him a copy of a Buddy Holly greatest hits album in which most of the songs are around two minutes or three minutes long, justifying why his songs should be kept short.[12] Francis later expressed that Norton was trying to give the band a more commercial sound and Francis wanted to keep it more grunge-like.[11] Production continued until December 12, 1988, with Norton and Haigler adding extra effects, including gated reverb to the mix. The master tapes were then sent for final post-production later that month.[13]

During the recording of Doolittle, tensions between Francis and Deal became visible to band members and the production team. Bickering and standoffs between the two marred the recording sessions and led to increased stress among the band members.[14] John Murphy, Deal's husband at the time, later recalled that, with Doolittle, the band dynamic "went from just all fun to work".[15] Exhaustion from touring and from releasing three records in two years contributed to the friction. The friction between Francis and Deal culminated at the end of the US post-Doolittle "Fuck or Fight" tour, and they did not attend their end-of-tour party.[16] Soon afterwards, the band announced that they were going on hiatus.[17]

Composition

Music

Francis wrote all the material for Doolittle with the exception of "Silver", which he co-wrote with Kim Deal.[18] The album features an eclectic mix of musical styles. "Crackity Jones" has a distinctly Spanish sound, incorporating G♯ and A triads over a C♯ pedal. The song's rhythm guitar, played by Francis, starts with an eighth-note downstroke typical of punk rock.[19] "Tame"'s three chord bass progression is overlaid by Joey Santiago's "Hendrix chord", and pivots on a sudden shift from quiet to loud,[20] a signature Pixie dynamic.[21] In contrast, "Monkey Gone to Heaven" features cellos and violins.[22]

Lyrics

The lyrics explore a variety of violent topics:[3] the opening song, "Debaser", mentions slicing eyes and the closing song, "Gouge Away", ends with everyone dying in a crush.[23] Black Francis often claimed that Doolittle's lyrics were words which just "fit together nicely", and that "the point [of the album] is to experience it, to enjoy it, to be entertained by it".[24]

"Debaser" contains references to surrealism; the lyrics "slicing up eyeballs" refers to Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí's 1929 film Un Chien Andalou.[25] Surrealism influenced Francis in his college years and throughout his career with the Pixies. Describing its influence on his songwriting method, he said "I got into avant-garde movies and Surrealism as an escape from reality. ... To me, Surrealism is totally artificial. I recently read an interview with the director David Lynch who said he had ideas and images but that he didn't know exactly what they meant. That's how I write."[26]

"Monkey Gone to Heaven" describes the human-caused environmental catastrophe in the ocean,[22] As Francis put it: "On one hand, it's this big organic toilet. Things get flushed and repurified or decomposed and it's this big, dark, mysterious place. It's also a very mythological place where there are octopus's gardens, the Bermuda Triangle, Atlantis, and mermaids." The song's lyrics question humanity's place in the universe. [27] The following song, "Mr. Grieves" takes the theme of destruction further, suggesting the human race it doomed to extinction.[28] Francis described "Wave of Mutilation" as being about "Japanese businessmen doing murder-suicides with their families because they'd failed in business, and they're driving off a pier into the ocean."[29] Imagery of the drowning and the sea are also used in "Mr. Grieves" and "Monkey Gone to Heaven".[30]

Two of the songs are based Old Testament stories of sex and death:[31] the story of David and Bathsheba in "Dead", and Samson and Delilah in "Gouge Away".[32] Francis' fascination with Biblical themes can be traced back to his teenage years; when he was twelve, he and his parents joined an evangelical church linked to the Assemblies of God. The themes also influenced the lyrics of "Monkey Gone to Heaven", the Devil being "six" and God being "seven".[22]

The lyrics for "Crackity Jones" allude to Francis' roommate during a student exchange trip to San Juan, Puerto Rico, whom he described as a "weird psycho gay roommate".[33] "La La Love You", which was sung by the band's drummer David Lovering, is seen as a satire of love songs.[34] Its tongue-in-cheek vocal style and simplistic lyrics (including the line "first base, second base, third base, home run") were a crude joke about sex.[35] Francis asked Lovering to provide vocals so it would be "a Ringo thing". Lovering initially refused, but according to Norton Francis was soon unable to "get him away from the microphone".[36]

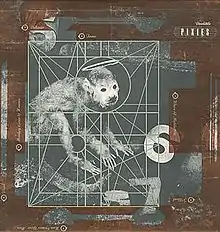

Artwork and title

The artwork was designed by photographer Simon Larbalestier and graphic artist Vaughan Oliver who had worked on the Pixies' previous albums, Come on Pilgrim and Surfer Rosa.[37] Larbalestier stated Doolittle was the first album where he and Oliver had access to the lyrics, which according to Larbalestier "made a fundamental difference", and he, like Francis, was interested in early surrealism.[38]

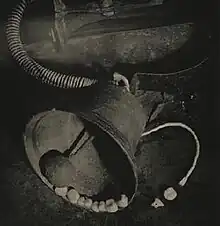

The artwork was designed by photographer Simon Larbalestier and graphic artist Vaughan Oliver who had worked on the Pixies' previous albums, Come on Pilgrim and Surfer Rosa.[37] Larbalestier stated Doolittle was the first album where he and Oliver had access to the lyrics, which "made a fundamental difference"[38] Larbalestier said that both Oliver and Francis supported the dark, macabre, and surreal images to illustrate the album. These were photographs constructed by juxtaposing two principle elements, such as a bell and teeth. Images included: Monkey Gone to Heaven, with a monkey and halo; "Tame", with a pelvic bone and stiletto; "Gouge Away", a spoon containing hair laid across a woman's torso.[39]

Around the time Oliver decided to portray a monkey and halo for the cover art, Francis discarded the working title Whore for the album. He later explained that he "thought people were going to think I was some kind of anti-Catholic or that I'd been raised Catholic and trying to get into this Catholic naughty-boy stuff. ... A monkey with a halo, calling it Whore, that would bring all kinds of shit that wouldn't be true. So I said I'd change the title."[9]

Release

In Fall 1988, Elektra Records began to take interest in the Pixies, and amid a bidding war, signed the band.[40] Elektra then began to negotiate with the Pixies' British label 4AD, which held their worldwide distribution rights, and released a promotional live album containing the album tracks "Debaser" and "Gouge Away" along with a selection of earlier material.[3] Two weeks before Doolittle released on April 2, 1989, Elektra and 4AD closed a deal that gave Elektra distribution rights in the US. By that time, PolyGram had already secured Canadian distribution rights.[41]

Doolittle was released in the UK on April 17, 1989, and in the US the following day. Elektra's major label status helped get retail displays for the record put up across the United States. Elektra also got "Monkey Gone to Heaven", the first single from the album, sent to major radio stations.[42]

Critical reception

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Chicago Tribune | |

| Los Angeles Times | |

| NME | 10/10[45] |

| Q | |

| Record Mirror | 4/5[47] |

| Rolling Stone | |

| Sounds | |

| The Village Voice | B+[50] |

When Doolittle was released, it was received positively by many critics,[25] NME critic Edwin Pouncey wrote that "the songs on Doolittle have the power to make you literally jump out of your skin with excitement". He singled out "Debaser" as one of the highlights, describing it as "blessed with the kind of beefy bass hook that originally brought "Gigantic" to life".[51] Q critic Peter Kane wrote that the album's "carefully structured noise and straightforward rhythmic insistence makes perfect sense".[52] Robert Christgau of The Village Voice wrote, "They're in love and they don't know why—with rock and roll, which is heartening in a time when so many college dropouts have lost touch with the verities". However, he concluded that "getting famous too fast could ruin them", while suggesting the lyrics reflect somewhat of a disconnection with "the outside world".[50]

Some reviewers were more critical. Spin ran a hundred-word review of the album, with critic Joe Levy finding "the insanity less surreal and more silly, and the songs themselves more like songs and less like adventures". Rolling Stone published "a tentative endorsement" of Doolittle, rating it three and a half stars;[53] reviewer Chris Mundy concluded, "The emphasis on more textured production has in no way taken away from the band's intensity. Francis is at all times in command of the album, quietly stringing us along before turning on us and screaming for attention."[48]

Doolittle appeared on several end-of-year "Best Album" lists. Both Rolling Stone and The Village Voice placed the album tenth, and independent music magazines Sounds and Melody Maker both ranked the album as the second-best of the year.[54] NME ranked the album fourth in their end-of-year list.[55]

| Publication | Country | Accolade | Year | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hot Press | Ireland | Top 100 Albums[56] | 2006 | 34 |

| NME | UK | 100 Best Albums[57] | 2003 | 2 |

| Pitchfork | US | Top 100 Albums of the 1980s[58] | 2002 | 4 |

| Rolling Stone | United States | The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time[59] | 2003 | 226 |

| 2012 | 227 | |||

| 2020 | 141 | |||

| Spin | US | 100 Greatest Albums, 1985–2005[60] | 2005 | 36 |

| Slant Magazine | US | Best Albums of the 1980s[61] | 2012 | 34 |

Sales

In the first week after its release in Britain,[42] Doolittle was number eight on the UK Albums Chart.[62] In the US, the album entered the Billboard 200 at number 171. With the help of college radio-play of "Monkey Gone to Heaven", it eventually rose to number 98,[63] spending two weeks in the Top 100.[64] Doolittle sold steadily in America, breaking sales of 100,000 after six months. By early 1992, while the band were supporting U2 on their Zoo TV Tour, the album was selling 1,500 copies per week. By the middle of 1993—two years after the release of the band's last album before their initial breakup, Trompe le Monde—Doolittle saw sales average 1,200 copies per week.[65] Doolittle was certified Gold by the Recording Industry Association of America in 1995 and Platinum in 2018.[66]

Ten years after their breakup, Doolittle continued to sell between 500 and 1,000 copies a week, and following their 2004 reunion tour sales reached 1,200 copies per week. At the end of 2005, best estimates put total US sales at between 800,000 and one million copies.[65] As of 2015, sales in the United States have exceeded 834,000 copies, according to Nielsen SoundScan.[67]

The band released a number of singles from the album. In 1997, "Debaser" was re-released to promote the Death to the Pixies compilation.[68] In June 1989, 4AD released "Here Comes Your Man" as the album's second single. It reached number three on the US Modern Rock Tracks chart and number 56 in the UK Singles Chart.[62][69] On May 6, 2019, "Here Comes Your Man" was certified Gold in Canada; On September 20, 2021, "Hey" was certified Gold in Canada.[70]

Legacy

| Aggregate scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Metacritic | 100/100[71] |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Blender | |

| The Guardian | |

| Mojo | |

| Pitchfork | 10/10[76] |

| Q | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Spin | A[80] |

| Uncut | 10/10[81] |

"Doolittle" consistently appears in numerous lists as one of the best albums of the 1980s and of all time.[54] In 2017, Pitchfork ranked it as the fourth best album of the 1980s;[82] a 2003 poll of NME writers ranked Doolittle as the second-greatest album of all time;[57] and Rolling Stone placed the album at 141 on its 2020 list of "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time".[83]

The album is widely regarded as one of the key alternative rock albums of the 1980s. It established the Pixies' loud—quiet dynamic,[84] which became highly influential on alternative rock.[85][21] After writing "Smells Like Teen Spirit", both Kurt Cobain and Krist Novoselic of Nirvana thought: "this really sounds like the Pixies. People are really going to nail us for this."[86] Norton was frequently credited with capturing the album's dynamics and became highly sought after by bands wishing to achieve a similar sound.[87] Fellow alternative musician PJ Harvey was "in awe" of "I Bleed" and "Tame", and described Francis's writing as "amazing".[88]

A 2002 Rolling Stone review gave it the maximum score five stars, remarking that it laid the "groundwork for Nineties rock".[78] The critic Michael Powell called "Doolittle" "their most famous album."[76] It was included in critic Robert Dimer's influential book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[89] PopMatters included it in their list of the "12 Essential 1980s Alternative Rock Albums" saying, "Doolittle, captured the musicians at the top of their game when it was released in 1989."[90]

Track listing

All tracks were written by Black Francis, except where noted.

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Debaser" | 2:52 | |

| 2. | "Tame" | 1:55 | |

| 3. | "Wave of Mutilation" | 2:04 | |

| 4. | "I Bleed" | 2:34 | |

| 5. | "Here Comes Your Man" | 3:21 | |

| 6. | "Dead" | 2:21 | |

| 7. | "Monkey Gone to Heaven" | 2:56 | |

| 8. | "Mr. Grieves" | 2:05 | |

| 9. | "Crackity Jones" | 1:24 | |

| 10. | "La La Love You" | 2:43 | |

| 11. | "No. 13 Baby" | 3:51 | |

| 12. | "There Goes My Gun" | 1:49 | |

| 13. | "Hey" | 3:31 | |

| 14. | "Silver" |

| 2:25 |

| 15. | "Gouge Away" | 2:45 | |

| Total length: | 38:38 | ||

Reissues

| Doolittle 25: B-Sides, Peel Sessions and Demos | |

|---|---|

| |

| Studio album by | |

| Released | December 1, 2014 |

| Length | 82:00 |

| Label | |

| Producer | Gil Norton |

Doolittle 25: B-Sides, Peel Sessions and Demos

To celebrate the 25th anniversary of the album, 4AD released a deluxe edition titled Doolittle 25, containing unreleased B-sides, demos and two full Peel sessions.[91] In addition to the original track listing, the reissue contained the following tracks, all of which were previously released unless otherwise indicated.

| No. | Title | Notes | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Dead" | Peel session, October 9, 1988 | 3:18 |

| 2. | "Tame" | Peel session, October 9, 1988; previously unreleased | 1:58 |

| 3. | "There Goes My Gun" | Peel session, October 9, 1988 | 2:18 |

| 4. | "Manta Ray" | Peel session, October 9, 1988 | 1:49 |

| 5. | "Into the White" | Peel session, April 16, 1989; previously unreleased | 4:11 |

| 6. | "Wave of Mutilation" | Peel session, April 16, 1989 | 2:31 |

| 7. | "Down to the Well" | Peel session, April 16, 1989 | 2:14 |

| 8. | "Manta Ray" | B-side of "Monkey Gone to Heaven" | 2:04 |

| 9. | "Weird at My School" | B-side of "Monkey Gone to Heaven" | 1:58 |

| 10. | "Dancing the Manta Ray" | B-side of "Monkey Gone to Heaven" | 2:14 |

| 11. | "Wave of Mutilation (UK Surf)" | B-side of "Here Comes Your Man" | 3:02 |

| 12. | "Into the White" | B-side of "Here Comes Your Man" | 4:43 |

| 13. | "Bailey's Walk" | B-side of "Here Comes Your Man" | 2:24 |

| No. | Title | Notes | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Debaser" | Previously released | 3:00 |

| 2. | "Tame" | 2:01 | |

| 3. | "Wave of Mutilation" | First demo | 2:04 |

| 4. | "I Bleed" | 1:46 | |

| 5. | "Here Comes Your Man" | 1986 demo; previously released | 3:07 |

| 6. | "Dead" | 1:35 | |

| 7. | "Monkey Gone to Heaven" | 2:52 | |

| 8. | "Mr. Grieves" | 1:42 | |

| 9. | "Crackity Jones" | 1:21 | |

| 10. | "La La Love You" | 2:08 | |

| 11. | "No. 13 Baby – VIVA LA LOMA RICA" | First demo | 2:17 |

| 12. | "There Goes My Gun" | 1:29 | |

| 13. | "Hey" | First demo | 3:22 |

| 14. | "Silver" | 2:11 | |

| 15. | "Gouge Away" | 1:42 | |

| 16. | "My Manta Ray Is All Right" | 2:03 | |

| 17. | "Santo" | Previously released as B-side of "Dig for Fire" | 2:17 |

| 18. | "Weird at My School" | First demo | 1:53 |

| 19. | "Wave of Mutilation" | 1:03 | |

| 20. | "No. 13 Baby" | Previously released | 3:07 |

| 21. | "Debaser" | First demo | 3:37 |

| 22. | "Gouge Away" | First demo | 2:08 |

On December 9, 2016, a limited Pure Audio Blu-Ray version of the album was released containing a 5.1 surround sound mix of the album by Kevin Vanbergen and a high definition stereo mix by Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab.[92]

In 2022, the album was formatted for Spatial Audio with Dolby Atmos and released exclusively on Apple Music.[93]

Personnel

Pixies

- Black Francis – vocals, rhythm guitar, acoustic guitar

- Kim Deal – bass guitar, vocals, acoustic slide guitar ("Silver")

- Joey Santiago – lead guitar, backing vocals

- David Lovering – drums, lead vocal ("La La Love You"), bass guitar ("Silver")

Additional musicians

- Karen Karlsrud – violin ("Monkey Gone to Heaven")

- Corine Metter – violin ("Monkey Gone to Heaven")

- Arthur Fiacco – cello ("Monkey Gone to Heaven")

- Ann Rorich – cello ("Monkey Gone to Heaven")

Technical

- Gil Norton – producer, engineer

- Dave Snider – assistant engineer

- Matt Lane – assistant engineer

- Steve Haigler – mixing

- Vaughan Oliver – art direction, design

- Simon Larbalestier – photography

- Chris Bigg – calligraphy

Charts

| Chart (1989) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Dutch Albums (Album Top 100)[94] | 53 |

| New Zealand Albums (RMNZ)[95] | 18 |

| UK Albums (OCC)[62] | 8 |

| US Billboard 200[63] | 98 |

| French Album Chart (SNEP)[96] | 66 |

Certifications

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Canada (Music Canada)[97] | Gold | 50,000^ |

| France (SNEP)[98] | Gold | 100,000* |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[99] | Platinum | 300,000* |

| United States (RIAA)[100] | Platinum | 1,000,000‡ |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

References

Citations

- Sisario 2006, pp. 19–20.

- Frank & Ganz 2006, p. 115.

- "Pixies". 4AD. p. 2. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved November 16, 2014.

- Sisario 2006, p. 21.

- Sisario 2006, pp. 44–45.

- Frank & Ganz 2006, pp. 139–140.

- Sisario 2006, pp. 46–47.

- Sisario 2006, p. 47.

- Sisario 2006, p. 54.

- Sisario 2006, pp. 55–57.

- Sisario 2006, p. 52.

- Frank & Ganz 2006, p. 142.

- Sisario 2006, pp. 57–58.

- Sisario 2006, p. 53.

- Frank & Ganz 2006, p. 144.

- Mendelssohn 2005, pp. 86–89.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Pixies > Biography". Allmusic. Archived from the original on April 26, 2011.

- Doolittle CD booklet.

- Sisario 2006, pp. 102–103.

- Sisario 2006, pp. 80–82.

- Edwards, Mark (August 8, 2004). "Pop: Loud quiet loud". The Sunday Times. London. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011. Retrieved March 16, 2007.

- Janovitz, Bill. "Monkey Gone to Heaven"". AllMusic. Archived from the original on June 5, 2012.

- Sisario 2006, pp. 117–121.

- Sisario 2006, p. 4.

- Hughes, Rob (April 17, 2018). "The Pixies: Looking back on Doolittle and the making of a classic". Louder. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020.

- Sisario 2006, p. 29.

- Sisario 2006, p. 96.

- Sisario 2006, pp. 99–101.

- Sisario 2006, pp. 82–83.

- Sisario 2006, p. 85.

- Sisario 2006, p. 92.

- Spitz, Marc (June 16, 2013). "Life to the Pixies". Spin. Archived from the original on June 7, 2015.

- Sisario 2006, p. 13.

- Mendelssohn 2005, p. 72.

- Sisario 2006, p. 104.

- Frank & Ganz 2006, pp. 141–142.

- Denney, Alex (October 1, 2018). "The Surreal secrets behind the Pixies' iconic sleeve art". Another Man. Archived from the original on November 8, 2018.

- Frank & Ganz 2006, p. 146.

- "Cover Story Interview- The Pixies- Doolittle- with photography by Simon Labalestier". Rockpop Gallery. April 30, 2009. Archived from the original on September 8, 2009. Also see the images in Frank & Ganz 2006, inset

- Sisario 2006, pp. 21–22.

- Sisario 2006, p. 22.

- Sisario 2006, p. 61.

- Kot, Greg (May 11, 1989). "The Pixies: Doolittle (Elektra)". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on April 11, 2022. Retrieved October 24, 2015.

- Hochman, Steve (May 28, 1989). "Pixies 'Doolittle.' Elektra". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 11, 2022. Retrieved October 24, 2015.

- Pouncey, Edwin (April 15, 1989). "Ape-Ocalypse Now!" (PDF). NME. p. 34. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 29, 2015. Retrieved August 23, 2015.

- Kane, Peter (May 1989). "Pixies: Doolittle". Q. No. 32.

- Levy, Eleanor (April 15, 1989). "Pixies: Doolittle". Record Mirror. p. 32.

- Mundy, Chris (July 13, 1989). "Pixies: Doolittle". Rolling Stone.

- Phillips, Shaun (April 15, 1989). "It's the end of the world (and I feel fine)". Sounds. p. 39.

- Christgau, Robert (November 21, 1989). "Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on August 15, 2013. Retrieved June 1, 2013.

- Pouncey, Edwin (April 15, 1989). "Ape-Ocalypse Now!" (PDF). NME. p. 34. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 29, 2015. Retrieved August 23, 2015.

- Frank & Ganz 2006, p. 150.

- Sisario 2006, pp. 62–63.

- "Pixies: Doolittle". Acclaimed Music. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved January 28, 2007.

- "NME's best albums and tracks of 1989". NME. October 10, 2016. Archived from the original on October 2, 2021.

- "Electric Ladyland (100/100 Greatest Albums Ever)". Hot Press. Archived from the original on March 11, 2007. Retrieved March 16, 2007.

- "Stone Glee!". NME. March 5, 2003. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023.

- "Top 100 Albums of the 1980s". Pitchfork. November 20, 2002. Archived from the original on May 22, 2009. Retrieved June 1, 2009.

- "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. September 22, 2020. Archived from the original on September 22, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- "100 Greatest Albums, 1985–2005". Spin. June 20, 2005. Archived from the original on March 12, 2007. Retrieved March 16, 2007.

- "The 100 Best Albums of the 1980s". Slant Magazine. March 5, 2012. Archived from the original on May 29, 2012. Retrieved March 18, 2012.

- "Pixies – The Official Charts Company". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on April 30, 2011. Retrieved April 17, 2011.

- "Pixies Album & Song Chart History". Billboard. Retrieved August 7, 2023.

- Sisario 2006, pp. 63–64.

- Sisario 2006, p. 69.

- RIAA. "RIAA Certification". Recording Industry Association of America. Archived from the original on March 8, 2007. Retrieved March 16, 2007.

- ""The Record: Unfinished Business". CapRadio. February 3, 2015. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015.

- Franks, Alison (January 30, 2010). "Dusting 'Em Off: Pixies – Doolittle". Consequence. Archived from the original on September 21, 2022.

- "Pixies Album & Song Chart History – Alternative Songs". Billboard. Retrieved August 7, 2023.

- "Gold/Platinum". Music Canada. Archived from the original on January 29, 2022.

- "Doolittle 25 by Pixies Reviews and Tracks". Metacritic. Archived from the original on September 17, 2021. Retrieved September 26, 2021.

- Phares, Heather. "Doolittle – Pixies". AllMusic. Archived from the original on November 24, 2021. Retrieved June 1, 2013.

- Dolan, Jon (December 2008 – January 2009). "Pixies: Doolittle". Blender. Vol. 7, no. 11. p. 86. Archived from the original on April 21, 2009. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- Petridis, Alexis (November 27, 2014). "Pixies: Doolittle 25 review – alt-rock milestone from US indie's weirdest stars". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 21, 2020. Retrieved April 11, 2022.

- Cameron, Keith (January 2015). "Animal crackers". Mojo. No. 254. p. 108.

- Powell, Mike (April 25, 2014). "Pixies: Catalog". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on April 10, 2022. Retrieved April 25, 2014.

- Segal, Victoria (January 2015). "The Debasement Tapes". Q. No. 342. p. 134.

- Kemp, Mark (November 28, 2002). "Pixies: Doolittle". Rolling Stone. No. 910. Archived from the original on November 1, 2007. Retrieved August 23, 2015.

- Wolk 2004, pp. 639–640.

- Milner, Greg (September 2004). "Rock Music: A Pixies Discography". Spin. Vol. 20, no. 9. p. 73. Retrieved April 11, 2022.

- Richards, Sam (January 2015). "Pixies: Doolittle 25". Uncut. No. 212. p. 89.

- "Top 100 Albums of the 1980s – Page 10". Pitchfork. November 21, 2002. Archived from the original on January 16, 2017. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- "500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. Retrieved August 7, 2023.

- Sisario 2006, p. 50.

- Tryneski, John (April 2, 2014). "Loud Quiet Loud: The Top 15 Pixies Songs". PopMatters. Archived from the original on May 1, 2019.

- Azerrad 1993, p. 176.

- "Eskimo Joe interview". Buzz Magazine Australia. Archived from the original on April 30, 2011. Retrieved September 10, 2006.

- Frank & Ganz 2006, p. 151.

- Dimery & Lydon 2010, p. 626.

- Makowsky, Jennifer (February 11, 2020). "Hope Despite the Times: 12 Essential Alternative Rock Albums from the 1980s". PopMatters. Archived from the original on January 22, 2018. Retrieved February 11, 2020.

- "Pixies: Doolittle 25 Announced, Pre-Order Now". 4AD. October 16, 2014. Archived from the original on July 24, 2019. Retrieved July 24, 2019.

- "Pixies : Pure Audio Blu-Ray Edition Of Doolittle Out Next Month". 4AD. November 11, 2016. Archived from the original on July 24, 2019. Retrieved July 24, 2019.

- Post by @pixiesofficial on Instagram. Published September 1, 2022. Accessed September 9, 2023.

- "Dutchcharts.nl – Pixies – Doolittle" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- "Charts.nz – Pixies – Doolittle". Hung Medien. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- "Tous les "Chart Runs" des Albums classés despuis 1985" (in French). InfoDisc. Archived from the original on August 20, 2008. Retrieved April 17, 2011. Note: The Pixies must be searched manually.

- "Canadian album certifications – Pixies – Doolittle". Music Canada. Retrieved July 2, 2023.

- "French album certifications – Pixies – Doolittle" (in French). Syndicat National de l'Édition Phonographique. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- "British album certifications – Pixies – Doolittle". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved July 2, 2023.

- "American album certifications – Pixies – Doolittle". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

Sources

- Azerrad, Michael (1993). Come as You Are: The Story of Nirvana. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-47199-8.

- Dimery, Robert; Lydon, Michael (March 23, 2010). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die (Revised and Updated ed.). Universe. ISBN 978-0-7893-2074-2.

- Frank, Josh; Ganz, Caryn (2006). Fool the World: The Oral History of a Band Called Pixies (first ed.). St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 0-312-34007-9.

- Mendelssohn, John (2005). Gigantic: The Story of Frank Black and the Pixies. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-8444-9490-3.

- Sisario, Ben (2006). Doolittle 33 1/3. Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-1774-9.

- Wolk, Douglas (2004). "The Pixies". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. pp. 639–640. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.