Tang dynasty painting

During the Tang dynasty, as a golden age in Chinese civilization, Chinese painting developed dramatically, both in subject matter and technique. The advancements in technique and style that characterized Tang painting had a lasting influence in the art of other countries, especially in East Asia (Korea, Japan, Vietnam) and central Asia.

A considerable amount of literary and documentary information about Tang painting has survived, but very few works, especially of the highest quality. A walled-up cave in the Mogao Caves complex at Dunhuang was discovered by Sir Aurel Stein, which contained a vast haul, mostly of Buddhist writings, but also some banners and paintings, making much the largest group of paintings on silk to survive. These are now in the British Museum and elsewhere. They are not of court quality, but show a variety of styles, including those with influences from further west. As with sculpture, other survivals showing Tang style are in Japan, though the most important, at Nara, was very largely destroyed in a fire in 1949.[1]

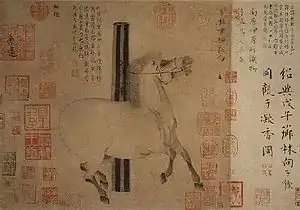

The rock-cut cave complexes and royal tombs also contain many wall-paintings. Court painting mostly survives in what are certainly or arguably copies from much later, though the front section of the famous portrait of the Emperor Xuanzong's horse Night-Shining White is probably an original by Han Kan of 740-760.[2]

The Tang dynasty saw the maturity of the landscape painting tradition known as shanshui (mountain-water) painting, which became the most prestigious type of Chinese painting, especially when practiced by amateur scholar-official or "literati" painters in ink-wash painting. In these landscapes, usually monochromatic and sparse, the purpose was not to reproduce exactly the appearance of nature but rather to grasp an emotion or atmosphere so as to catch the "rhythm" of nature. The long-lasting tradition of the Southern School began in this period.[3]

Early period

(1) Buddhist art depicting musicians in paradise, a mural from the Yulin Caves of Dunhuang, Tang dynasty

(2) an armed cortege, mural from the tomb of Li Xian at the Qianling Mausoleum, early 8th century AD

(3) painting on a silk scroll of a female dancer from the Astana Cemetery of Gaochang (Turpan), c. 702 AD

(4) female figure as the planet Venus from the painting "Tejaprabhā Buddha and the Five Planets" (熾盛光佛並五星圖), depicted as playing the pipa, c. 897 AD

During the early Tang period, the painting style was mainly inherited from the previous Sui dynasty. In this period, the "painting of people" (人物畫) developed greatly. Buddhist painting and "court painting" played a major role, including paintings of the Buddha, monks, nobles etc.

One of the first landscape murals is located in Han Xiu's tomb.[4]

Brothers Yan Liben (閻立本) and Yan Lide (閻立德) were among the most prolific painters of this period. Yan Liben was the personal portraitist to the Emperor Taizong, and his most notable works include the Thirteen Emperors Scroll (歷代帝王圖).

Mid and Late period

The landscape (shan shui) painting technique developed quickly in this period and reached its first maturation. Li Sixun (李思訓) and Li Zhaodao (李昭道) (father and son) were the most famous painters in this domain. During this time painters overcame the basics of depth perception and utilizing the area being painted. This allowed the artists to depict a more realistic appearance to the landscape paintings.[5]

The painting of people also reached a climax. The outstanding master in this field is Wu Daozi (吳道子), who is referred to as the "Sage of Painting". Wu's works include God Sending a Son (天王送子圖). Wu created a new technique of drawing named "Drawing of Water Shield" (蒓菜描). Most Tang artists outlined figures with fine black lines and used brilliant color and elaborate detail filling in the outlines. However, Wu Daozi used only black ink and freely painted brushstrokes to create ink paintings that were so exciting that crowds gathered to watch him work. From his time on, ink paintings were no longer thought to be preliminary sketches or outlines to be filled in with color. Instead, they were valued as finished works of art.

Zhou Fang (周昉) followed from the genius of Wu Daozi, his contemporary. Zhou painted for the Emperor, the themes of his artwork would cover religious subjects and everyday life.[6] He created paintings that represented goddesses who were modeled after imperial court ladies, a development that indicated religious painting was to become more realistic, and that secular painting was beginning to take on its initial form. His portrait paintings emphasized real life, and as forerunners of secular lady paintings, they had a big influence on later paintings of court ladies.[7]

The great poet Wang Wei (王維) first created the brush and ink painting of shan-shui, literally "mountains and waters" (水墨山水畫). He further combined literature, especially poetry, with painting. The use of line in painting became much more calligraphic than in the early period.

The theory of painting also developed, and Buddhism, Taoism, and traditional literature were absorbed and combined into painting. Paintings on architectural structures, such as murals (壁畫), ceiling paintings, cave paintings, and tomb paintings, were very popular. An example is the paintings in the Mogao Caves in Xinjiang during this period.

See also

Notes

- Sullivan, 132-133

- Sullivan, 134-135

- Sullivan, 136-139

- "Earliest landscape mural of Tang Dynasty unearthed". Shaanxi Provincial Bureau of Cultural Heritage. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- Cartwright, Mark (11 Oct 2017). "Tang dynasty art". World History Encyclopedia. Creative Commons. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- "Zhou Fang | Chinese painter | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-04-25.

- "Skillful Court Lady Painters". 2005-03-17. Archived from the original on 17 March 2005. Retrieved 2022-04-25.

References

- Sullivan, Michael, The Arts of China, 1973, Sphere Books, ISBN 0351183345 (revised edn of A Short History of Chinese Art, 1967)

- Eichenbaum, Patricia. Arts of the Tang Court. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Loehr, Max. The Great Painters of China. New York: Harper & Row, 1980.