Tarpeian Rock

The Tarpeian Rock (/tɑːrˈpiːən/; Latin: Rupes Tarpeia or Saxum Tarpeium; Italian: Rupe Tarpea) is a steep cliff on the south side of the Capitoline Hill, which was used in Ancient Rome as a site of execution. Murderers, traitors, perjurors, and larcenous slaves, if convicted by the quaestores parricidii, were flung from the cliff to their deaths.[1] The cliff was about 25 meters (80 ft) high.[2]

History

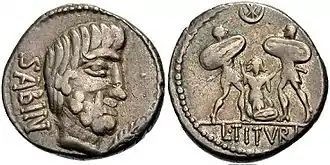

According to early Roman histories, when the Sabine ruler Titus Tatius attacked Rome after the Rape of the Sabines (8th century BC), the Vestal Virgin Tarpeia, daughter of Spurius Tarpeius, governor of the citadel on the Capitoline Hill, betrayed the Romans by opening the Porta Pandana gate for Titus Tatius in return for "what the Sabines bore on their arms" (golden bracelets and bejeweled rings). In Book 1 of Livy's Ab Urbe Condita, the Sabines "having been accepted into the citadel, [the Sabines] killed her, having been overwhelmed by weapons, and "scuta congesta", meaning, "[they] heaped up shields [on her]".[3] The Sabines crushed her to death with their shields, and her body was buried in the rock that now bears her name. Regardless of whether or not Tarpeia was buried in the rock itself, it is significant that the rock was named for her deceit.[4]

About 500 BC, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, the seventh legendary king of Rome, levelled the top of the rock, removing the shrines built by the Sabines, and built the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus on the intermontium, the area between the two summits of the hill. The rock itself survived the remodelling and was used for executions well into Sulla's time[5] (early 1st century BC). However the execution of Simon bar Giora was as late as the time of Vespasian.

There is a Latin phrase, Arx tarpeia Capitoli proxima ('the Tarpeian Rock is close to the Capitol'), a warning that one's fall from grace can come swiftly.

To be hurled off the Tarpeian Rock was, from a certain perspective, a fate worse than mere death, because it carried with it the stigma of shame. The standard method of execution in ancient Rome was by strangulation in the Tullianum. The rock was reserved for the most notorious traitors and as a place of unofficial, extra-legal executions such as the near-execution of then-Senator Gaius Marcius Coriolanus by a mob whipped into frenzy by a tribune of the plebs.[6]

Notable victims

Victims of this punishment included:[7]

- Spurius Cassius Vecellinus, 485 BC, for perduellio (i.e. high treason)

- Marcus Manlius Capitolinus, 384 BC, for sedition[8]

- Rebels from Tarentum, 212 BC

- Lucius Cornelius Chrysogonus, 80 BC

- Syllaeus or Syllaios, 6 BC

- Aelius Saturninus, 23 AD

- Sextus Marius, a rich man from Spain with copper and gold mines confiscated by Tiberius and executed in 33 AD after being accused of incest.[9] [10]

- Barbatius Philippus

- Simon bar Giora, 70 AD

In fiction

- The Tarpeian Rock is briefly mentioned in Act Three, Scene Three of the Shakespeare tragedy Coriolanus. In lines 87–90, Coriolanus warns:

"Let them pronounce the steep Tarpeian death,/

Vagabond exile, flaying, pent to linger/ But with a grain a day; I would not buy/

Their mercy at the price of one fair word."

In lines 99–104, Sicinius Velutus gives judgement:

"we/ Even from this instant, banish him our city,/

In peril of precipitation/ From off the rock Tarpeian, never more/

To enter our Rome gates."

- In Miguel de Cervantes's Don Quixote The image of Nero watching the burning of Rome is related to the fires of passion. In Part 1, Chapter 14 Ambrosio accuses Marcela of being a cruel Nero. In Part 2, Chapter 44, Altisidora accuses Don Quixote of being a new Nero who watches her burn with love from the Tarpeian Rock: "No mires de tu Tarpeya / este incendio que me abrasa / Neron manchego del mundo."[11]

- In Asterix and the Laurel Wreath, the jailer at the Circus Maximus remarks to Asterix and Obelix that, while they are getting a gourmet feast leading up to the day they are thrown to the lions: "Those who are thrown from the Tarpeian Rock are given solid, heavy food."

- In Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Marble Faun, a character is murdered by another character by being thrown from the Tarpeian Rock.

- Canto IX of Purgatory of the Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri has a reference to the Tarpeian Rock. When Metellusus yielded to Julius Caesar, the rock, close by, was said to creak when the door to the treasury was opened. The symbolic meaning is obvious as Caesar was criticized for robbing the public treasury of Roman Republic.

- In the HBO TV series Rome, Julius Caesar refers to the site while trying to motivate his soldiers to march to Rome in opposition to the Senate.

- In A Capitol Death by Lindsey Davis, three deaths involve falls from the Tarpeian Rock.[12]

- The Tarpeian Cliff is mentioned multiple times in I, Claudius by Robert Graves, as a place of execution by hurling over the edge.

- In The Cantos, Ezra Pound includes reference to the 'Rupe Tarpeia' in "Notes for CXVII etc seq.": "Under the Rupe Tarpeia/ weep out your jealousies--/ To make a church/ or an altar to Zagreus/ Son of Semele/ Without jealousy/ like the double arch of a window/ Or some great colonnade."

See also

References

- Platner (1929). A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome, Tarpeius Mons, pp509-510. London. Oxford University Press.

- Lemprière, John (1827). A Classical Dictionary. E. Duychinck, Collin & co. p. 797. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- Livy (June 1991). Ab Urbe Condita. Macmillan Education Ltd. p. 20. ISBN 0-86292-296-8.

- Pseudo-Plutarch. Parallela Graeca et Romana. (Authorship disputed) (Loeb ed.).

Tarpeia, one of the maidens of honourable estate, was the guardian of the Capitol when the Romans were warring against the Sabines. She promised Tatius that she would give him entry to the Tarpeian Rock if she received as pay the necklaces that the Sabines wore for adornment. The Sabines understood the import and buried her alive. So Aristeides the Milesian in his Italian History.

- Plutarch. Lives – Sylla. trans. Joseph Dryden.

And afterwards, when he had seized the power into his hands, and was putting many to death, a freedman, suspected of having concealed one of the proscribed, and for that reason sentenced to be thrown down the Tarpeian rock, in a reproachful way recounted how they had lived long together under the same roof, himself for the upper rooms paying two thousand sesterces, and Sylla for the lower three thousand; so that the difference between their fortunes then was no more than one thousand sesterces, equivalent in Attic coin to two hundred and fifty drachmas.

- Plutarch. Lives – Coriolanus. Translated by Joseph Dryden.

But, when, instead of the submissive and deprecatory language expected from him, he began to use not only an offensive kind of freedom, seeming rather to accuse than apologize, but, as well by the tone of his voice as the air of his countenance, displayed a security that was not far from disdain and contempt of them, the whole multitude then became angry, and gave evident signs of impatience and disgust; and Sicinnius, the most violent of the tribunes, after a little private conference with his colleagues, proceeded solemnly to pronounce before them all, that Marcius was condemned to die by the tribunes of the people, and bid the Aediles take him to the Tarpeian rock, and without delay throw him headlong from the precipice.... Sicinnius then, after a little pause, turning to the patricians, demanded what their meaning was, thus forcibly to rescue Marcius out of the people's hands, as they were going to punish him; when it was replied by them, on the other side, and the question put, 'Rather, how came it into your minds, and what is it you design, thus to drag one of the worthiest men of Rome, without trial, to a barbarous and illegal execution?'

- Plutarch, Lives; Livy, Ab Urbe Condita; M. Grant, Roman Myths.

- Livy. Book 6 [20.9]

- Haley 2010:143

- Tacitus Annals 6.19.1

- Frederick A. de Armas, "To See What Men Cannot: Teichoskopia in Don Quixote I" Cervantes: Bulletin of the Cervantes Society of America 28.1 (2008), pp. 83-102.

- Davis, Lindsey (2019). A Capitol Death. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-1-473-65874-5.

Sources

- Grant, Michael (1971), Roman Myths, New York: Scribner's, pg 123.

- Livy, Book 1

- Twelve Tables