Tashan Weir

Tashan Weir (Chinese: 它山堰; pinyin: Tuōshān yàn) also called Tuoshan Weir or Tuoshanyan[1] is an ancient dam that was erected under Emperor Tang Wenzong during the Tang dynasty in 833. The dam is located in Tashanyan Village, Yinjiang Town, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang, China. Originally designed under the supervision of Wang Yuanwei, who was the administrator of Yin County, the dam was constructed to prevent tidal sea water from accessing the banks of the Fenghua River and to store water during periods of severe drought. The dam later became part of a large-scale irrigation system serving Ningbo City. This infrastructure is particularly notable because it is recognized as a historical site protected by the state.[2]

它山堰 | |

| |

| 29.769607°N 121.347248°E | |

| Location | Tashanyan Village, Yinjiang Town, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang, China |

|---|---|

| Designer | Wang Yuanwei |

| Type | Dam |

| Length | 110 metres (360 ft) |

| Completion date | 833 |

History

Prior to the dam's construction, the surrounding area experienced devastating floods from torrential rains that arrived every summer and autumn due to the local sub-tropical climate. In combination with the flat terrain and the high salt content of the Fenghua River, the floods decimated crops and caused bouts of famine. To remedy this situation, Wang Yuanwei, a magistrate originally from Shandong, proposed the construction of Tashan Weir. The dam was completed in 833 with the aim of decreasing the risk of flooding and permanently removing salt water from arable land.

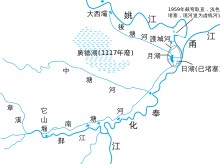

The dam was also used to divert water in two different directions. The first stream flows along the Nantang River, serving Dongqiao, Hengzhang, Beidu, Lishe, Shiqi and Duantang, until it reaches the city of Ningbo intra-muros before pouring into the man-made Moon Lake (Chinese: 月湖; pinyin: Yuè hú) and Sun Lake (Chinese: 日湖; pinyin: Rì hú) which no longer exists today. The second stream flows north, serving Xiaoxi, Meiyuan and Shenjiao.

In total, the hydraulic system of Tashan Weir (the dam, two flows, and ancillary facilities) has been irrigating nearly 16,000 hectares of land for centuries, and continues to do so even today. The Ningbo area experienced rapid growth due to the stable water supply that the dam provided.

Construction

The dam is about 110 meters long and its top is approximately 5 meters wide. Its outer part is composed of roughly regular stones (2 to 3 meters long and 0.2 to 0.35 meters thick) while its internal structure consists of a mixture of stone and wood. To consolidate the structure, molten iron was directly injected in some sections. The dam was designed to adjust according to the flow of the river and to mitigate risks associated with natural geological erosion. Maintenance and restructuring work have been continuously carried out, from the imperial dynasties to the present day.

The design of the facility ensured that in cases of excessive rain, 70 percent of the flood water flows to the Zhang River (inner river) while the remaining 30 percent discharges to the Nantang River (outer river).[3] This proportion of water flow is reversed during periods of drought, achieved through the use of water gates between the inner and outer rivers.

Legacy

Tashan Weir was officially declared a Major Historical and Cultural Site Protected at the National Level on January 13, 1988 (Number 3-55). It is also recognized as one of the four most important water conservation projects of imperial or pre-imperial China, along with the Zhengguo Canal, Lingqu Canal, and Dujiangyan. A temple with a statue representing Wang Yuanwei and ten builders of Tashan Weir was built nearby, and important ceremonies and cultural festivities are regularly held there.

Gallery

View from the northern bank of the river

View from the northern bank of the river First edge of the dam

First edge of the dam Second edge of the dam

Second edge of the dam View from the west

View from the west View from the east

View from the east Holes where molten iron was introduced

Holes where molten iron was introduced Temple dedicated to Wang Yuanwei

Temple dedicated to Wang Yuanwei Stele marking the emplacement of the temple

Stele marking the emplacement of the temple Statue of Wang Yuanwei

Statue of Wang Yuanwei

See also

References

Citations

- The 它 of 它山堰 is read as "Tuō" and not as "Tā"

- angelakis, Andreas; Mays, Larry; Koutsoyiannis, Demetris; Mamassis, Nikos (2012). Evolution of Water Supply Through the Millennia. London: IWA Publishing. p. 198. ISBN 9781843395409.

- Angelakis et al., p. 198.

Bibliography

- Andreas N. Angelakis, Larry W. Mays, Demetris Koutsoyiannis, Nikos Mamassis, Evolution of Water Supply Through the Millennia.

- Han Zhang, China’s Local Entrepreneurial State and New Urban Spaces: Downtown.

- Yongxiang Lu, A History of Chinese Science and Technology, Volume 3.