Technology life cycle

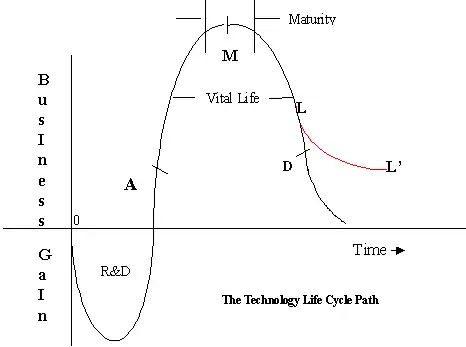

The technology life-cycle (TLC) describes the commercial gain of a product through the expense of research and development phase, and the financial return during its "vital life". Some technologies, such as steel, paper or cement manufacturing, have a long lifespan (with minor variations in technology incorporated with time) while in other cases, such as electronic or pharmaceutical products, the lifespan may be quite short.[1]

The TLC associated with a product or technological service is different from product life-cycle (PLC) dealt with in product life-cycle management. The latter is concerned with the life of a product in the marketplace with respect to timing of introduction, marketing measures, and business costs. The technology underlying the product (for example, that of a uniquely flavoured tea) may be quite marginal but the process of creating and managing its life as a branded product will be very different.

The technology life cycle is concerned with the time and cost of developing the technology, the timeline of recovering cost, and modes of making the technology yield a profit proportionate to the costs and risks involved. The TLC may, further, be protected during its cycle with patents and trademarks seeking to lengthen the cycle and to maximize the profit from it.

The product of the technology may be a commodity such as polyethylene plastic or a sophisticated product like the integrated circuits used in a smartphone.

The development of a competitive product or process can have a major effect on the lifespan of the technology, making it shorter. Equally, the loss of intellectual property rights through litigation or loss of its secret elements (if any) through leakages also work to reduce a technology's lifespan. Thus, it is apparent that the management of the TLC is an important aspect of technology development.

Most new technologies follow a similar technology maturity lifecycle describing the technological maturity of a product. This is not similar to a product life cycle, but applies to an entire technology, or a generation of a technology.

Technology adoption is the most common phenomenon driving the evolution of industries along the industry lifecycle. After expanding new uses of resources they end with exhausting the efficiency of those processes, producing gains that are first easier and larger over time then exhaustingly more difficult, as the technology matures.

The four phases of the technology life-cycle

The Soviet economist Nikolai Kondratiev was the first to observe technology life-cycle in his book The Major Economic Cycles (1925).[2][3][4] Today, these cycles are called Kondratiev wave, the predecessor of TLC. TLC is composed of four phases:

- The research and development (R&D) phase (sometimes called the "bleeding edge") when incomes from inputs are negative and where the prospects of failure are high

- The ascent phase when out-of-pocket costs have been recovered and the technology begins to gather strength by going beyond some Point A on the TLC (sometimes called the "leading edge")

- The maturity phase when gain is high and stable, the region, going into saturation, marked by M, and

- The decline (or decay phase), after a Point D, of reducing fortunes and utility of the technology.

S-curve

The shape of the technology lifecycle is often referred to as S-curve.[5]

Technology perception dynamics

There is usually technology hype at the introduction of any new technology, but only after some time has passed can it be judged as mere hype or justified true acclaim. Because of the logistic curve nature of technology adoption, it is difficult to see in the early stages whether the hype is excessive.

The two errors commonly committed in the early stages of a technology's development are:

- fitting an exponential curve to the first part of the growth curve, and assuming eternal exponential growth

- fitting a linear curve to the first part of the growth curve, and assuming that take-up of the new technology is disappointing

Similarly, in the later stages, the opposite mistakes can be made relating to the possibilities of technology maturity and market saturation.

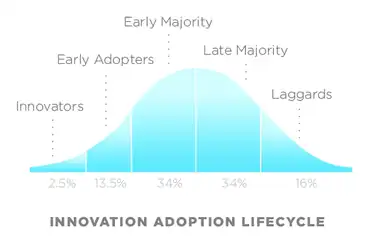

The technology adoption life cycle typically occurs in an S curve, as modelled in diffusion of innovations theory. This is because customers respond to new products in different ways. Diffusion of innovations theory, pioneered by Everett Rogers, posits that people have different levels of readiness for adopting new innovations and that the characteristics of a product affect overall adoption. Rogers classified individuals into five groups: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards. In terms of the S curve, innovators occupy 2.5%, early adopters 13.5%, early majority 34%, late majority 34%, and laggards 16%.

The four stages of technology life cycle are as follows:[6]

- Innovation stage: This stage represents the birth of a new product, material of process resulting from R&D activities. In R&D laboratories, new ideas are generated depending on gaining needs and knowledge factors. Depending on the resource allocation and also the change element, the time taken in the innovation stage as well as in the subsequent stages varies widely.

- Syndication stage: This stage represents the demonstration and commercialisation of a new technology, such as, product, material or process with potential for immediate utilisation. Many innovations are put on hold in R&D laboratories. Only a very small percentage of these are commercialised. Commercialisation of research outcomes depends on technical as well non-technical, mostly economic factors.

- Diffusion stage: This represents the market penetration of a new technology through acceptance of the innovation, by potential users of the technology. But supply and demand side factors jointly influence the rate of diffusion.

- Substitution stage: This last stage represents the decline in the use and eventual extension of a technology, due to replacement by another technology. Many technical and non-technical factors influence the rate of substitution. The time taken in the substitution stage depends on the market dynamics.

Licensing options

Large corporations develop technology for their own benefit and not with the objective of licensing. The tendency to license out technology only appears when there is a threat to the life of the TLC (business gain) as discussed later.[7]

Licensing in the R&D phase

There are always smaller firms (SMEs) who are inadequately situated to finance the development of innovative R&D in the post-research and early technology phases. By sharing incipient technology under certain conditions, substantial risk financing can come from third parties. This is a form of quasi-licensing which takes different formats. Even large corporates may not wish to bear all costs of development in areas of significant and high risk (e.g. aircraft development) and may seek means of spreading it to the stage that proof-of-concept is obtained.

In the case of small and medium firms, entities such as venture capitalists or business angels, can enter the scene and help to materialize technologies. Venture capitalists accept both the costs and uncertainties of R&D, and that of market acceptance, in reward for high returns when the technology proves itself. Apart from finance, they may provide networking, management and marketing support. Venture capital connotes financial as well as human capital.

Larger firms may opt for Joint R&D or work in a consortium for the early phase of development. Such vehicles are called strategic alliances – strategic partnerships.

With both venture capital funding and strategic (research) alliances, when business gains begin to neutralize development costs (the TLC crosses the X-axis), the ownership of the technology starts to undergo change.

In the case of smaller firms, venture capitalists help clients enter the stock market for obtaining substantially larger funds for development, maturation of technology, product promotion and to meet marketing costs. A major route is through initial public offering (IPO) which invites risk funding by the public for potential high gain. At the same time, the IPOs enable venture capitalists to attempt to recover expenditures already incurred by them through part sale of the stock pre-allotted to them (subsequent to the listing of the stock on the stock exchange). When the IPO is fully subscribed, the assisted enterprise becomes a corporation and can more easily obtain bank loans, etc. if needed.

Strategic alliance partners, allied on research, pursue separate paths of development with the incipient technology of common origin but pool their accomplishments through instruments such as 'cross-licensing'. Generally, contractual provisions among the members of the consortium allow a member to exercise the option of independent pursuit after joint consultation; in which case the optee owns all subsequent development.

Licensing in the ascent phase

The ascent stage of the technology usually refers to some point above Point A in the TLC diagram but actually it commences when the R&D portion of the TLC curve inflects (only that the cashflow is negative and unremunerative to Point A). The ascent is the strongest phase of the TLC because it is here that the technology is superior to alternatives and can command premium profit or gain. The slope and duration of the ascent depends on competing technologies entering the domain, although they may not be as successful in that period. Strongly patented technology extends the duration period.

The TLC begins to flatten out (the region shown as M) when equivalent or challenging technologies come into the competitive space and begin to eat away marketshare.

Till this stage is reached, the technology-owning firm would tend to exclusively enjoy its profitability, preferring not to license it. If an overseas opportunity does present itself, the firm would prefer to set up a controlled subsidiary rather than license a third party.

Licensing in the maturity phase

The maturity phase of the technology is a period of stable and remunerative income but its competitive viability can persist over the larger timeframe marked by its 'vital life'. However, there may be a tendency to license out the technology to third parties during this stage to lower risk of decline in profitability (or competitivity) and to expand financial opportunity.

The exercise of this option is, generally, inferior to seeking participatory exploitation; in other words, engagement in joint venture, typically in regions where the technology would be in the ascent phase, as say, a developing country. In addition to providing financial opportunity it allows the technology-owner a degree of control over its use. Gain flows from the two streams of investment-based and royalty incomes. Further, the vital life of the technology is enhanced in such strategy.

Licensing in the decline phase

After reaching a point such as D in the above diagram, the earnings from the technology begin to decline rather rapidly. To prolong the life cycle, owners of technology might try to license it out at some point L when it can still be attractive to firms in other markets. This, then, traces the lengthening path, LL'. Further, since the decline is the result of competing rising technologies in this space, licenses may be attracted to the general lower cost of the older technology (than what prevailed during its vital life).

Licenses obtained in this phase are 'straight licenses'. They are free of direct control from the owner of the technology (as would otherwise apply, say, in the case of a joint-venture). Further, there may be fewer restrictions placed on the licensee in the employment of the technology.

The utility, viability, and thus the cost of straight-licenses depends on the estimated 'balance life' of the technology. For instance, should the key patent on the technology have expired, or would expire in a short while, the residual viability of the technology may be limited, although balance life may be governed by other criteria such as knowhow which could have a longer life if properly protected.

It is important to note that the license has no way of knowing the stage at which the prime, and competing technologies, are on their TLCs. It would, of course, be evident to competing licensor firms, and to the originator, from the growth, saturation or decline of the profitability of their operations.

The license may, however, be able to approximate the stage by vigorously negotiating with the licensor and competitors to determine costs and licensing terms. A lower cost, or easier terms, may imply a declining technology.

In any case, access to technology in the decline phase is a large risk that the licensee accepts. (In a joint-venture this risk is substantially reduced by licensor sharing it). Sometimes, financial guarantees from the licensor may work to reduce such risk and can be negotiated.

There are instances when, even though the technology declines to becoming a technique, it may still contain important knowledge or experience which the licensee firm cannot learn of without help from the originator. This is often the form that technical service and technical assistance contracts take (encountered often in developing country contracts). Alternatively, consulting agencies may fill this role.

Technology development cycle

According to the Encyclopedia of Earth, "In the simplest formulation, innovation can be thought of as being composed of research, development, demonstration, and deployment."[8]

Technology development cycle describes the process of a new technology through the stages of technological maturity:

See also

- Background, foreground, sideground and postground intellectual property

- Business cycle

- Disruptive technology

- Mass customization

- Network effects

- New product development

- Technological revolution

- Technological transitions

- Technology acceptance model

- Technology adoption life cycle

- Technology readiness level (TRL)

- Technology roadmap

- Toolkits for user innovation

- Open innovation

- Frugal innovation

References

- group of authors (2015). Proceedings of IAC-MEM 2015 in Vienna. Czech Institute of Academic Education z.s., 2015. p. 91. ISBN 9788090579156.

- "Kondratiev, Nikolai Dmitrievich | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2021-03-07.

- "Kondratiev, Nikolai (1892–1938) - Encyclopedia of Modern Europe: Europe Since 1914: Encyclopedia of the Age of War and Reconstruction | HighBeam Research". 2013-05-23. Archived from the original on 2013-05-23. Retrieved 2021-03-07.

- Ayres, Robert U. (1988). "Barriers and breakthroughs: an "expanding frontiers" model of the technology-industry life cycle". Technovation. 7 (2): 87–115. doi:10.1016/0166-4972(88)90041-7.

- Dr. Chandana Jayalath (22 April 2010). "Understanding S-curve Innovation". Improvementandinnovation.com. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- Technology Management - Growth & Lifecycle, Shahid kv, Sep 28, 2009, Attribution Non-commercial

- Bayus, B. (1998). An Analysis of Product Lifetimes in a Technologically Dynamic Industry. Management Science, 44(6), pp.763-775.

- "Technological Innovation". Encyclopedia of Earth. Retrieved 27 January 2016.