Thaba Bosiu

Thaba Bosiu is a constituency and sandstone plateau with an area of approximately 2 km2 (0.77 sq mi) and a height of 1,804 meters above sea level. It is located between the Orange and Caledon Rivers in the Maseru District of Lesotho, 24 km east of the country's capital Maseru.[1] It was once the capital of Lesotho, having been King Moshoeshoe's stronghold.

| Thaba Bosiu | |

|---|---|

| Thaba Bosiu Plateau | |

Thaba Bosiu seen from its northern slopes | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 1,804 m (5,919 ft) |

| Coordinates | 29.3503°S 27.6713°E |

| Geography | |

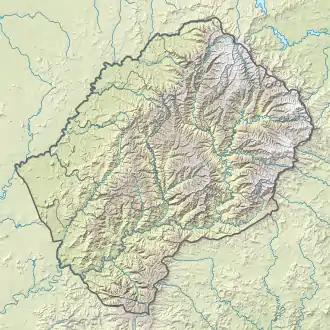

Thaba Bosiu Location of Thaba Bosiu in Lesotho | |

| Country | Lesotho |

| Geology | |

| Type of rock | Basalt and Quartzite |

Moshoeshoe

Thaba Bosiu was used as a hideout by Moshoeshoe I and his subjects after they migrated from Butha-Buthe in 1824 escaping the ravages of the Difaqane/Mfecane Wars. The plateau formed a natural fortress which protected the Basotho in times of war. Moshoeshoe I and his people took occupation of this mountain in July 1824. He named it Thaba Bosiu (loosely translated – Mountain at Night) because he and his people arrived at night.[2] To intimidate his enemies, he spread news that the mountain grew larger at night. Moshoeshoe was able to offer cattle and protection to those fleeing the ravages of Mfecane/Difaqane Wars. When Moshoeshoe settled in Thaba Bosiu, he sent for many people to be rounded up by his regiments. They were given food and shelter. The plateau's large area meant it could hold enough livestock and provisions to support the people during a lengthy siege.[3]

Once satisfied that they were safe, he sent the people out, but many remained under his rule. This gave birth to the Basotho nation; Thaba Bosiu served as a capital for his new Basotho nation. It also became the centre of organised resistance to European encroachment into the central plateau region of South Africa.[4][5]

Physical description

The mountain has eight springs and six passes, the main one being Khubelu pass. The other passes are known as Ramaseli, Maebeng, Mokachane, Makara and Rahebe.[6] It is flat topped and is situated in the valley of the Phuthiatsana River. It is approximately 24 km east of the junction of the Caledon River that divides Lesotho from Free State. It rises about 106m from the surrounding valley and its summit is surrounded by a belt of perpendicular cliffs some 12m on the average. Nearby, there is San rock art.[4]

In 1837, Private David Webber from the 72nd Seaforth Highlanders reached Thaba Bosiu, where he was given refuge/sanctuary. He was a good mason and carpenter, and thus built Moshoeshoe a stone house. It was a rectangular building measuring 10 metres by five metres and was divided internally into two rooms. Moshoeshoe had four other stone buildings erected as part of his compound – three of which were rectangular and one cylindrical.[5]

Beliefs

Many Basotho believe that the mountain preserved magical properties. One belief is that if an individual takes some dirt from the mountain, he will find that it is gone in the morning, having returned to the mountain.[7] As also mentioned above, news was spread as a form of intimidation to the enemies that the mountain grew larger at night.[8]

Attacks

Mzilikazi attempted to attack Moshoeshoe I at Thaba Bosiu, trying to gather strength after escaping Shaka Zulu's rule; but was unsuccessful in his conquest.[9]

European invaders in 1852 and the Boers of the Orange Free State were unable to storm Moshoeshoe's mountain during the siege of Thaba Bosiu on 18 August 1865. Louw Wepener and 6 000 armed Boers volunteered to charge Thaba Bosiu. Their strategy was simply for the Free State Artillery (Vrystaatse Artillerie Regiment) to bombard the top of the mountain. As they approached, only 100 Boers were still with Wepener by 5pm and others had retreated to the Boer lines. Wepener made it to the top of Khubelu pass only to have his head struck by a bullet. He is the only enemy ever to reach the mountain top and has been linked to it as Khubelu pass is also known as Wepener's pass. The siege of Thaba Bosiu continued until January 1866 when General Jan Fick and his men returned to Free State to reorganise.[10]

Treaty of Thaba Bosiu

Due to being starved after the siege, the Basotho signed a treaty in April 1866 in which they agreed to surrender 3 000 cattle. They also surrendered more than two-thirds of their arable land. At the time, Basotho faced large scale starvation and thus Moshoeshoe and his subjects agreed to the Orange Free State's terms. The land they forfeited during this treaty included conquered territory on the west of the bank of the Caledon River and Orange River. This left Basotho with a significantly reduced cultivable area close to Thaba Bosiu, as well as 32 km of arable soil on the east bank of the Caledon River. Villagers, however, did not vacate the surrendered territory and in March 1867, Orange Free State President Johannes Henricus Brand ordered both a resumption and intensification of Free State military action.[11]

In 1867, After the Third Free State–Basotho War, when Free State conquered the whole Lowlands, Moshoeshoe requested British protection which was granted in March 1868 on the eve of the Boer attack on Thaba Boisu. Lesotho became a British territory. Thaba Bosiu was the only part of the territory which had remained invincible.[10]

Thaba Bosiu Affair

On 27 December 1966, Moshoeshoe II organised protest meetings which culminated in a prayer meeting at Thaba Bosiu. This was a reaction to Prime Minister Chief Leabua Jonathan’s governance (leader of the Basotho National Party - BNP). Moshoeshoe II contested the legitimacy of the BNP governance and his lack of executive powers in the governance of Lesotho. When the prayer meeting was held, Chief Jonathan perceived this defiance as a promotion of insurrection and banned the meeting. A conflict between the security forces and demonstrators ensued, resulting in 10 dead and arrests of many opposition party leaders. Under house arrest, Moshoeshoe II was forced to sign a document promising not to convene or address public gatherings without consent of his government and to present only speeches required and prepared by the government.[12]

National monument

In 1967, the Lesotho government declared the mountain a national monument. In the 1990s, the United Nation Development Programme in conjunction with the Basotho government, initiated the Preservation and Presentation of Thaba Bosiu, the national monument to preserve this historical landmark. This mountain has become a tourist attraction, with a conference centre, a cultural village and many rondavel type of accommodation.[7]

In 1996, Moshoeshoe II was buried on the mountain, joining Moshoeshoe I. To keep the cultural significance, several political organisations held meetings or rallies at Thaba Bosiu. For example, Lekhotla la Bafo (a political organisation) held many meetings on top of the mountain. In 1957, Lekhotla la Bafo held a joint meeting with the Basotoland Congress Party (BCP) at Thaba Bosiu.[7]

In 2017 the relationships between the site and its local communities was studied by Nthabiseng Mokoena.[13]

References

- Thaba Bosiu; Encyclopædia Britannica 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica Online Library Edition. 7 Apr. 2008 .

- Coulson, David; Clarke, James (1983). Mountain odyssey in Southern Africa. Internet Archive. Macmillan South Africa. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-86954-137-1.

- Hull, Richard W. (1976). African Cities and Towns before the European Conquest. Norton. p. 23. ISBN 0-393-09166-X.

- "What to see: Thaba Bosiu Mountain". Lesotho: The Kingdom in the sky. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- Rosenberg, Scott (2013). Historical Dictionary of Lesotho. UK: Scarecrow Press. p. 506. ISBN 9780810879829.

- Futhwa, Fezekile (2011). Setho: Afrikan thought and belief system. Alberton: Nalane ka Fezekile Futhwa. p. 152. ISBN 9780620503952.

- Rosenberg, Scott (2013). Historical Dictionary of Lesotho. UK: Scarecrow Press. p. 507. ISBN 9780810879829.

- Hull 1976, p. 23.

- Mzolo, Shoks (4 September 2015). "Thaba Bosiu: Where the mountain is king". Mail and Guardina. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- Stapleton, Timothy J (2017). Encyclopedia of African Colonial Conflicts (Volume 2). Santa Barbara. pp. 299–300. ISBN 9781440849060.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Rosenberg, Scott (2013). Historical Dictionary of Lesotho. UK: Scarecrow Press. p. 508. ISBN 9780810879829.

- Stapleton 2017, p. 300.

- "Can Archaeology achieve Social Justice? | Canon Collins Educational and Legal Assistance Trust". www.canoncollins.org.uk. Retrieved 2021-01-25.

External links

Thaba Bosiu travel guide from Wikivoyage

Thaba Bosiu travel guide from Wikivoyage