Black-browed albatross

The black-browed albatross (Thalassarche melanophris), also known as the black-browed mollymawk,[3] is a large seabird of the albatross family Diomedeidae; it is the most widespread and common member of its family.

| Black-browed albatross | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Procellariiformes |

| Family: | Diomedeidae |

| Genus: | Thalassarche |

| Species: | T. melanophris |

| Binomial name | |

| Thalassarche melanophris | |

| |

| Black-browed albatross range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Diomedea melanophris | |

Taxonomy

Mollymawks are albatrosses in the family Diomedeidae and order Procellariiformes, which also includes shearwaters, fulmars, storm petrels, and diving petrels. These birds share certain identifying features. They have nasal passages that attach to the upper bill called naricorns, although the nostrils on the albatross are on the sides of the bill. The bills of Procellariiformes are also unique in that they are split into between seven and nine horny plates. They produce a stomach oil made up of wax esters and triglycerides that is stored in the proventriculus. This is used against predators as well as being an energy-rich food source for chicks and also for the adults during their long flights.[4] The albatross also has a salt gland above the nasal passage which helps to remove salt from the ocean water that they imbibe. The gland excretes a high saline solution through the bird's nose.[5]

In 1998, Robertson and Nunn published their view that the Campbell albatross (Thalassarche impavida), should be split from this species (T. melanophris).[6] Over the course of the next few years, others agreed, including BirdLife International in 2000,[7] and Brooke in 2004.[8] James Clements did not adopt the split,[9] the ACAP has not yet adopted the split, and the SACC recognizes the need for a proposal.[10]

The black-browed albatross was first described as Diomedea melanophris by Coenraad Jacob Temminck, in 1828, based on a specimen from the Cape of Good Hope.[11]

Etymology

The origin of the name melanophris comes from two Greek words melas or melanos, meaning "black", and ophris, meaning "eyebrow", referring to dark feathering around the eyes.[12]

Description

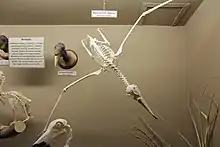

The black-browed albatross is a medium-sized albatross, at 80 to 95 cm (31–37 in) long with a 200 to 240 cm (79–94 in) wingspan and an average weight of 2.9 to 4.7 kg (6.4–10.4 lb).[3] It can have a natural lifespan of over 70 years. It has a dark grey saddle and upperwings that contrast with the white rump, and underparts. The underwing is predominantly white with broad, irregular, black margins. It has a dark eyebrow and a yellow-orange bill with a darker reddish-orange tip. Juveniles have dark horn-colored bills with dark tips, and a grey head and collar. They also have dark underwings. The features that distinguish it from other mollymawks (except the closely related Campbell albatross) are the dark eyestripe which gives it its name, a broad black edging to the white underside of its wings, white head and orange bill, tipped darker orange. The Campbell albatross is very similar but with a pale eye. Immature birds are similar to grey-headed albatrosses but the latter have wholly dark bills and more complete dark head markings.

Range and habitat

| Location | Population | Date | Trend |

|---|---|---|---|

| Falkland Islands | 399,416 pairs | 2007 | Decreasing 0.7% yr |

| South Georgia Island | 74,296 pairs | 2006 | Decreasing |

| Chile | 122,000 pairs | 2007 | |

| Antipodes Island | ? | 1998 | |

| Campbell Island | ? | 1998 | |

| Heard Island | 600 pairs | 1998 | Increasing |

| McDonald Island | ? | 1998 | |

| Crozet Islands | ? | 1998 | |

| Kerguelen Islands | ? | 1998 | Decreasing |

| Macquarie Island | ? | 1998 | |

| Snares Islands | ? | 1998 | |

| Greenland[13] | ? | 1978 | Increasing |

| Total | 600,000 pairs | 2005 | Decreasing |

The black-browed albatross is circumpolar in the southern oceans, and it breeds on 12 islands throughout that range. In the Atlantic Ocean, it breeds on the Falkland Islands, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, and the Cape Horn Islands.[14] In the Pacific Ocean it breeds on Islas Ildefonso, Diego de Almagro, Islas Evangelistas, Campbell Island, Antipodes Islands, Snares Islands, and Macquarie Island. In the Indian Ocean it breeds on the Crozet Islands, Kerguelen Islands, Heard Island, and McDonald Island.[15]

There are an estimated 1,220,000 birds alive with 600,853 breeding pairs, as estimated by a 2005 count. Of these birds, 402,571 breed in the Falklands, 72,102 breed on South Georgia Island, 120,171 breed on the Chilean islands of Islas Ildefonso, Diego de Almagro, Islas Evangelistas, and Islas Diego Ramírez. 600 pairs breed on Heard Island, Finally, the remaining 5,409 pairs breed on the remaining islands.[11][16][17] This particular species of albatross prefers to forage over shelf and shelf-break areas. Falkland Island birds winter near the Patagonian Shelf, and birds from South Georgia forage in South African waters, using the Benguela Current, and the Chilean birds forage over the Patagonian Shelf, the Chilean Shelf, and even make it as far as New Zealand. It is the most likely albatross to be found in the North Atlantic due to a northerly migratory tendency. There have been 20 possible sightings in the Continental United States.[18]

Behaviour

Colonies are very noisy as they bray to mark their territory, and also cackle harshly. They use their fanned tail in courting displays.[3]

Feeding

The black-browed albatross feeds on fish, squid, crustaceans, carrion, and fishery discards.[19][20][21] This species has been observed stealing food from other species.[3]

Reproduction

This species normally nests on steep slopes covered with tussock grass and sometimes on cliffs; however, on the Falklands it nests on flat grassland on the coast.[7] They are an annual breeder laying one egg from between 20 September and 1 November, although the Falklands, Crozet, and Kerguelen breeders lay about three weeks earlier. Incubation is done by both sexes and lasts 68 to 71 days. After hatching, the chicks take 120 to 130 days to fledge. Juveniles will return to the colony after two to three years but only to practice courtship rituals, as they start breeding around the 10th year.[3]

Conservation

Until 2013, the IUCN classified this species as endangered due to a drastic reduction in population.[22] Bird Island near South Georgia Island had a 4% per year loss of nesting pairs,[17] and the Kerguelen Island population had a 17% reduction from 1979 to 1995.[23] Diego Ramírez decreased in the 1980s but has rebounded recently,[24][25] and the Falklands had a surge in the 1980s[15][26] probably due to abundant fish waste from trawlers;[27] however, recent censuses have shown drastic reduction in the majority of the nesting sites there.[16] There has been a 67% decline in the population over 64 years.[7]

Increased longline fishing in the southern oceans, especially around the Patagonian Shelf and around South Georgia has been attributed as a major cause of the decline of this bird,[28][29][30][31] The black-browed albatross has been found to be the most common bird killed by fisheries.[29][30][32][33][34][35][36] Trawl fishing, especially around the Patagonian Shelf[37] and near South Africa, is also a large cause of deaths.[38]

Conservation efforts underway start with this species being placed on Convention on Migratory Species Appendix II, and Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels Annex 1. It is being monitored on half of the islands, and most of the breeding sites are reserves. Heard Island, McDonald Island, Macquarie Island, and the New Zealand islands are World Heritage Sites. An initial Chilean census has also been completed.[39]

Vagrancy

Although this is a rare occurrence, on several occasions a black-browed albatross has summered in Scottish gannet colonies (Bass Rock, Hermaness and now Sula Sgeir) for a number of years. Ornithologists believe that it was the same bird, known as Albert, who lives in north Scotland.[40][41] It is believed that the bird was blown off course into the North Atlantic in 1967.[41] A similar incident took place in the gannet colony in the Faroe Islands island of Mykines, where a black-browed albatross lived among the gannets for over 30 years. This incident is the reason why an albatross is referred to as a "gannet king" (Faroese: súlukongur) in Faroese.[42] In July 2013 the first recorded sighting of a black-browed albatross in the Bahamas was made from the Bahamas Marine Mammal Research Organisation's research vessel, off Sandy Point, Abaco. For four consecutive years from 2014 on, a bird - probably the same individual named Albert - has been sighted over Heligoland, and on the east coast of England.[43][44][45][46]

Footnotes

- BirdLife International. 2018. Thalassarche melanophris. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T22698375A132643647. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22698375A132643647.en. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- Brands, S. (2008)

- Robertson, C. J. R. (2003)

- Double, M. C. (2003)

- Ehrlich, Paul R. (1988)

- Robertson, C. J. R. & Nunn (1998)

- BirdLife International (2008)

- Brooke, M. (2004)

- Clements, J. (2007)

- Remsen Jr., J. V. (2008)

- Robertson, G.; et al. (2007)

- Gotch, A. F. (1995)

- https://www.scran.ac.uk/packs/exhibitions/learning_materials/webs/40/albatross.htm Gorman, Martyn (2002)

- Gardner, Jacob (2011). "Thalassarche melanophrys black-browed albatros". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- Croxall, J. P. & Gales, R. (1998)

- Huin, N. & Reid, T. (2007)

- Poncet, S.; et al. (2006)

- Dunn, Jon L. & Alderfer, Jonathan (2006)

- Cherel, Y.; et al. (2002)

- Xavier, J. C.; et al. (2003)

- Arata, J.; et al. (2003)

- BirdLife International (2013)

- Weimerskirch, H. & Jouventin, P. (1998)

- Schlatter, R. P. (1984)

- Arata, J. & Moreno, C. A. (2002)

- Gales, R. (1998)

- Thompson, K. R. & Riddy, M. D. (1995)

- Prince, P. A.; et al. (1998)

- Schiavini, A.; et al. (1998)

- Stagi, A.; et al. (1998)

- Tuck, G. & Polacheck, T. (1997)

- Gales, R.; et al. (1998)

- Murray, T. E.; et al. (1993)

- Ryan, P. G. & Boix-Hinzen, C. (1998)

- Ryan, P. G.; et al. (2002)

- Reid, T. A. & Sullivan, B. J. (2004)

- Sullivan, B. J. & Reid, T. A. (2002)

- Watkins, B. P.; et, al (2007)

- Lawton, K.; et al. (2004)

- Ivens, Martin (9 May 2007)

- "No romance for lovesick albatross". BBC. 9 May 2007. Retrieved 9 May 2007.

- á Ryggi, M. (1951)

- Fotonachweise vom 28./29. Mai, 4./5. Juni und 12./13. Juni 2014 auf Helgoland. Bericht mit Fotos in Der Falke Nr. 8/2014, S. 34–37.

- "Beobachtungsnachweise bei birdguides.com". Archived from the original on 21 April 2015. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- Sighting on Heligoland, 2016 (German)

- Sighting on Heligoland, 2017 (German)

References

- Alsop, III, Fred J. Smithsonian Birds of North America. Dorling Kindersley ISBN 0-7894-8001-8

- Arata, J.; Moreno, C. A. (2002). "Progress report of Chilean research on albatross ecology and conservation". Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources Working Group on Fish Stock Assessment.

- Arata, J.; Robertson, G.; Valencia, J.; Lawton, K (2003). "The Evangelistas Islets, Chile: a new breeding site for black-browed albatrosses". Polar Biology. 26 (10): 687–690. doi:10.1007/s00300-003-0536-6. S2CID 30265392.

- BirdLife International (2008). "Black-browed Albatross – BirdLife Species Factsheet". Data Zone. Archived from the original on 2 January 2009. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- Brands, Sheila. "Taxon: Species Thalassarche melanophris". The Taxonomicon. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

- Brooke, M. (2004). "Procellariidae". Albatrosses And Petrels Across The World. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850125-1.

- Cherel, Y.; Weimerskirch, H.; Trouve, C. (2002). "Dietary evidence for spatial foraging segregation in sympatric albatrosses (Diomedea spp.) rearing chicks at Iles Nuageuses, Kerguelen". Marine Biology. 141 (6): 1117–1129. doi:10.1007/s00227-002-0907-5. S2CID 83653436.

- Clements, James (2007). The Clements Checklist of the Birds of the World (6th ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4501-9.

- Croxall, J. P.; Gales, R. (1998). "Assessment of the conservation status of albatrosses". In Robertson, G.; Gales, R. (eds.). Albatross biology and conservation. Chipping Norton, Australia: Surrey Beatty & Sons.

- Double, M. C. (2003). "Procellariiformes (Tubenosed Seabirds)". In Hutchins, Michael; Jackson, Jerome A.; Bock, Walter J.; Olendorf, Donna (eds.). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Vol. 8 Birds I Tinamous and Ratites to Hoatzins. Joseph E. Trumpey, Chief Scientific Illustrator (2nd ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group. pp. 107–111. ISBN 978-0-7876-5784-0.

- Dunn, Jon L.; Alderfer, Jonathan (2006). "Albatrosses". In Levitt, Barbara (ed.). National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America (fifth ed.). Washington D.C.: National Geographic Society. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-7922-5314-3.

- Ehrlich, Paul R.; Dobkin, David, S.; Wheye, Darryl (1988). The Birder's Handbook (First ed.). New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. pp. 29–31. ISBN 978-0-671-65989-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gales, R. (1998). "Albatross populations: status and threats". In Robertson, G.; Gales, R. (eds.). Albatross biology and conservation. Chipping Norton, Australia: Surrey Beatty & Sons.

- Gales, R.; Brothers, N.; Reid, T. (1998). "Seabird mortality in the Japanese tuna longline fishery around Australia, 1988–1995". Biological Conservation. 86: 37–56. doi:10.1016/s0006-3207(98)00011-1.

- Gotch, A. F. (1995) [1979]. "Albatrosses, Fulmars, Shearwaters, and Petrels". Latin Names Explained A Guide to the Scientific Classifications of Reptiles, Birds & Mammals. New York, NY: Facts on File. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-8160-3377-5.

- Huin, N.; Reid, T. (April 2007). "Census of the Black-browed Albatross population of the Falkland Islands, 2000 and 2005" (PDF). Falklands Conservation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2009.

- Ivens, Martin (9 May 2007). "The lonely albatross looking for love in all the wrong places". The Times. London: Lewis Smith. Retrieved 10 May 2007.

- Lawton, K.; Robertson, G.; Valencia, J.; Wienecke, B.; Kirkwood, R. (2003). "The status of Black-browed Albatrosses Thalassarche melanophrys at Diego de Almagro Island, Chile". Ibis. 145 (3): 502–505. doi:10.1046/j.1474-919x.2003.00186.x.

- Murray, T. E.; Bartle, J. A.; Kalish, S. R.; Taylor, P. R. (1993). "Incidental capture of seabirds by Japanese southern bluefin tuna longline vessels in New Zealand waters, 1988–1992". Bird Conservation International. 3 (3): 181–210. doi:10.1017/s0959270900000897. S2CID 85632223.

- Poncet, S.; Robertson, G.; Phillips, R. A.; Lawton, K.; Phalan, B.; Trathan, P. N.; Croxall, J. P. (2006). "Status and distribution of wandering Black-browed and Grey-headed Albatrosses breeding at South Georgia". Polar Biology. 29 (9): 772–781. doi:10.1007/s00300-006-0114-9. S2CID 21411990.

- Prince, P. A.; Croxall, J. P.; Trathan, P. N.; Wood, A. G. (1998). "The pelagic distribution of South Georgia albatrosses and their relationships with fisheries". In Robertson, G.; Gales, R. (eds.). Albatross biology and conservation. Chipping Norton, Australia: Surrey Beatty & Sons.

- Reid, T. A.; Sullivan, B. J. (2004). "Longliners, black-browed albatross mortality and bait scavenging in Falkland Island waters: what is the relationship?". Polar Biology. 27 (3): 131–139. doi:10.1007/s00300-003-0547-3. S2CID 28900918.

- Remsen Jr., J. V.; et al. (7 August 2008). "A classification of the bird species of South America". South American Classification Committee. American Ornithologists' Union. Archived from the original on 2 March 2009. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- Robertson, C. J. R. (2003). "Albatrosses (Diomedeidae)". In Hutchins, Michael; Jackson, Jerome A.; Bock, Walter J.; Olendorf, Donna (eds.). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Vol. 8 Birds I Tinamous and Ratites to Hoatzins. Joseph E. Trumpey, Chief Scientific Illustrator (2nd ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-7876-5784-0.

- Robertson, G.; Moreno, C. A.; Lawton, K.; Arata, J.; Valencia, J.; Kirkwood, R. (2007). "An estimate of the population sizes of Black-browed (Thalassarche melanophrys) and Grey-headed (T. chrysostoma) Albatross breeding in the Diego Ramírez Archipelago, Chile". Emu. 107 (3): 239–244. doi:10.1071/mu07028. S2CID 83796801.

- Robertson, C. J. R.; Nunn, G. B. (1998). "Towards a new taxonomy for albatrosses". In Robertson, G.; Gales, R. (eds.). Albatross biology and conservation. Chipping Norton, Australia: Surrey Beatty & Sons. pp. 13–19.

- Ryan, P.G.; Boix-Hinzen, C. (1998). "Tuna long-line fisheries off southern Africa: the need to limit seabird bycatch". South African Journal of Science. 94: 179–182. hdl:10520/AJA00382353_9022.

- Ryan, P. G.; Keith, D. G.; Kroese, M. (2002). "Seabird bycatch by tuna longline fisheries off southern Africa, 1998–2000". South African Journal of Marine Science. 24: 103–110. doi:10.2989/025776102784528565.

- Schiavini, A.; Frere, E.; Gandini, P.; Garcia, N.; Crespo, E. (1998). "Albatross-fisheries interactions in Patagonian shelf waters". In Robertson, G.; Gales, R. (eds.). Albatross biology and conservation. Chipping Norton, Australia: Surrey Beatty & Sons. pp. 208–213.

- Schlatter, R. P. (1984). "The status and conservation of seabirds in Chile". In Croxall, J. P.; Evans, P. G. H.; Schreiber, R. W. (eds.). Status and conservation of the world's seabirds. Cambridge, U.K.: International Council for Bird Preservation (Techn. Publ.). pp. 261–269.

- Stagi, A.; Vaz-Ferreira, R.; Marin, Y.; Joseph, L. (1998). "The conservation of albatrosses in Uruguayan waters". In Robertson, G.; Gales, R. (eds.). Albatross biology and conservation. Chipping Norton, Australia: Surrey Beatty & Sons. pp. 220–224.

- Sullivan, B.; Reid, T. (2002). "Seabird interactions/mortality with longliners and trawlers in the Falkland/Malvinas Island waters". Unpublished Report. CCAMLR-WG-FSA-02/36.

- Thompson, K. R.; Riddy, M. D. (1995). "Utilisation of offal discards from finfish trawlers around the Falkland Islands by the Black-browed Albatross Diomedea melanophris". Ibis. 137 (2): 198–206. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919x.1995.tb03240.x.

- Tuck, G.; Polacheck, T. (1997). Trends in tuna long-line fisheries in the Southern Oceans and implications for seabird by-catch: 1997 update. Hobart, Australia: Division of Marine Research.

- Watkins, B. P.; Petersen, S. L.; Ryan, P. G. (2007). "Interactions between seabirds and deep-water hake trawl gear: an assessment of impacts in South African waters". Animal Conservation. 11 (4): 247–254. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2008.00192.x.

- Weimerskirch, H.; Jouventin, P. (1998). "Changes in population sizes and demographic parameters of six albatross species breeding on the French sub-antarctic islands". In Robertson, G.; Gales, R. (eds.). Albatross biology and conservation. Chipping Norton, Australia: Surrey Beatty and Sons. pp. 84–91.

- Xavier, J. C.; Croxall, J. P.; Trathan, P. N.; Wood, A. G. (2003). "Feeding strategies and diets of breeding grey-headed and wandering albatrosses at South Georgia". Marine Biology. 143 (2): 221–232. doi:10.1007/s00227-003-1049-0. S2CID 85569322.

_01.jpg.webp)