Thancoupie

Dr Thancoupie Gloria Fletcher James AO (1937-2011) was an Australian sculptural artist, educator, linguist and elder of the Thainakuith people in Weipa, in the Western Cape York area of far north Queensland. She was the last fluent speaker of the Thainakuith language and became a pillar of cultural knowledge in her community. She was also known as Thankupi, Thancoupie and Thanakupi.

Thancoupie | |

|---|---|

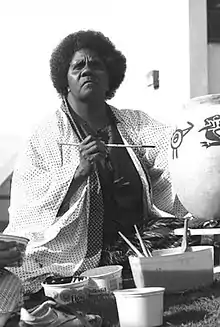

Thancoupie 1981 | |

| Born | 1937 |

| Died | 23 April 2011 (aged 73–74) |

| Other names | Thanakupie, Thancoupie, Gloria Fletcher, Thankupi, Dr Gloria Fletcher James AO |

| Known for | Ceramics, Sculpture |

Thancoupie played a dynamic role in First Nations Australian arts, not only in her leadership of ceramics as a form of cultural expression for First Peoples, but was among the first to be recognised as an individual contemporary First Nations artist in Australia.

Thancoupie also produced a number of works using metal, including her large-scale cast bronze work Eran (2010) which is displayed at the entrance to the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra.[1] Thancoupie’s works in metal closely resemble her ceramic works: rounded vessels or spheres, into which imagery from Thainakuith culture is carved. Thancoupie’s use of metal in her practice was, like ceramics, among the first uses of the material as a vehicle for cultural expression in a First Nations context.

Thancoupie drew directly from her knowledge of Thainakuith culture, as well as ceramic and metal art practices, to produce her body of work. Thancoupie’s works occupy most Australian public collections and remains a pivotal figure in Australian art history.[2][3]

Early life

Thancoupie was born in 1937 at Weipa to Ida and Jimmy James and was given the name Thanakupi which means "wattle flower" in the Thaynakwith language.[4][5] She was later given the name Gloria James at her baptism.[5] She had a twin sister who died young.[6]

In 1945, Thancoupie’s father died while stationed on Thursday Island as a World War Two serviceman.[7]

Thancoupie grew up in the small Napranum community and attended the mission school there before studying ceramics in Sydney.[5] In rediscovering her language, she adopted the name Thancoupie but she also used the variant spelling Thanakupi.[5]

In 1957 bauxite mining began in Western Cape York and as a result, Thainakuith land became occupied by non-Indigenous people and culture. Gradually Thainakuith land became increasingly subject to bauxite mining and forced the dislocation of a large portion of the community there, causing the significant loss of local cultural knowledge. Thancoupie’s body of work would become a response to this decision by the Queensland government to encroach upon Thainakuith land, and Thancoupie would also go on to participate in broader political Land Rights protests.[8][7]

Thancoupie emerged in the art world as a painter, holding her first exhibition in Cairns in 1968. Her painted works were shown alongside Dick Roughsy’s Mornington Island bark paintings. Thancoupie grew up using clay in a ceremonial context, and this direct contact with Country and ancestry inspired her training as a ceramicist in Sydney. Thancoupie held her first ceramics exhibition in Volta and became closely associated with Aboriginal communities and activist groups in Sydney, as well as a prominent member of the arts and crafts community.[7]

In 1976, after completing her Fine Arts degree in Sydney, Thancoupie relocated to Cairns and established a pottery studio there. From 1976 to 1983 Thancoupie travelled internationally as a representative to the World Crafts Council, advocating the importance of ceramics in the process of cultural regeneration for First Nations Australians. In 1986 Thancoupie became the Australian Cultural Commissioner to the Sao Paulo Biennale in Brazil.[9]

Career

Thancoupie worked as a ceramic artist, story teller, educator, community leader, advocate, and negotiator.[5]

Thancoupie began her career as a preschool children's educator while pursuing her art part-time.[2] In 1969 she moved from far north Queensland to study art and ceramics at East Sydney Technical College.[2][10]

The use of ceramics in exploring ancestry, aesthetics and Country is a recent development in the arts of First Nations artists in Australia. Unlike the First Peoples across the Americas, Africa and Asia, ceramics is not an ancient means of cultural communication in Australia, but rather a contemporary movement which has arisen in response to a changing creative environment for Australia’s First Peoples. Thancoupie’s body of work and educational career is testament to the ways in which the art of Thainakuith people, and more broadly First Nations peoples, continues to transform whilst remaining poignant records of ongoing cultural significance.[11]

Thancoupie together with the Tiwi potter Eddy Puruntatamerri, were founders of Australia’s Indigenous ceramic art movement.[12] Thancoupie's work is represented in the collections of the National Gallery of Australia as well as art galleries and museums in Victoria, Queensland, South Australia and Queensland.[12] Eran 2010, a sculptural piece is at the entrance to the National Gallery of Australia.[2][13] Thancoupie mounted more than 20 solo exhibitions in Australia and overseas.[2]

Community leader and storyteller

The life work of Thancoupie has been recording the language and stories of the Thaynakwith people.[5][14][15] She began telling her community's stories through clay, tile and other ceramic arts.[5] The Weipa Festival, a celebration of indigenous art and performance from all over Australia held at Weipa,[2] was founded by Thancoupie.

Storytelling remains a major function of artworks produced by First Nations Australian artists. Perhaps in response to the ongoing effects of colonisation in Australia, the production of objects made from enduring materials such as metal and fired ceramics allow artists such as Thancoupie to preserve the histories, languages and belief systems through material culture. Thancoupie demonstrates the ability for ceramic and sculpture practices of First Nations Australian artists to continually expand and take on new significances.[16]

Works

- Thancoupie, Gloria Fletcher; Thancoupie, Gloria Fletcher (2007), Thanakupi's guide to language & culture : a Thaynakwith dictionary, Jennifer Isaacs Arts & Publishing, ISBN 978-0-9803312-0-2

- Thanakupi. "Mosquito corroboree". AGNSW collection record - Thanakupi. Art Gallery of New South Wales. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- "Eran, (2010) by Thanakupi". cs.nga.gov.au. Retrieved 14 April 2016.[17]

Awards

- 1998 honorary doctorate from the University of Queensland[18]

- 2003 Order of Australia — Officer of the Order of Australia (AO) As: Fletcher-James, Thanacoupie Gloria[5]

- 2006 Visual Arts Emeritus Award by the Australia Council for the Arts for her career as an Indigenous artist, teacher, and community leader[5]

- 2008 Queensland Greats Awards[5][19]

Personal life

Thancoupie died in 2011[20] after a long illness, aged 74, at Weipa Base Hospital on Cape York.[21][22]

References

- Caruana, Cubillo, Wally, Franchesca (2010). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art: Collection Highlights. Canberra: National Gallery of Australia.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "About Thancoupie - Thancoupie's Bursary Fund". www.thancoupiebursary.com. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- Donnelly, Paul (6 May 2011). "Thancoupie (Thanakupi) The Potter (1937-2011)". Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences. Archived from the original on 5 May 2019. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- "Message Stick - Thancoupie". www.abc.net.au. Archived from the original on 31 July 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- "Thancoupie Gloria Fletcher". AustLit. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- Nicholls, Christine. "Artist kept her people's culture and language alive". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 14 March 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ""Thanakupi: Peer Reviewed Biography"". Design & Art Australia Online. 22 April 2019. Archived from the original on 5 May 2019.

- Wright, Simon (2006). "Thanakupi: First Hand in Weipa, Brisbane and Sydney". Art Monthly. 196 – via Griffith University.

- "Thancoupie (1937-2011)". Royal Australian Historical Society. 28 March 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- Hood, Robbie. "Thanakupi – Indigenous Australian ceramic artist". Ceramics and Pottery Arts and Resources. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- DeBoos, Janet (November 2005). "Using Clay / Coming Home". The Australian Journal of Ceramics: 48–51.

- Newstead, Adrian. "Australian Indigenous Art Market Top 100". www.aiam100.com. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- "Eran". cs.nga.gov.au. Archived from the original on 21 March 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- Thancoupie, Gloria Fletcher; Thancoupie, Gloria Fletcher (2007), Thanakupi's guide to language & culture : a Thaynakwith dictionary, Jennifer Isaacs Arts & Publishing, ISBN 978-0-9803312-0-2

- "Jennifer Isaacs: Thancoupie". www.jenniferisaacs.com.au. Archived from the original on 1 March 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- Isaacs, Jennifer (1982). Thancoupie the Potter. Sydney: Aboriginal Arts Agency. p. 66.

- "NGA collaborates with UAP to produce two major commissions for 'new look' gallery". urbanartprojects.wordpress.com. Urban Art Projects. Archived from the original on 28 September 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- "Thancoupie, 1981". National Portrait Gallery collection. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- "2008 Queensland Greats recipients". www.qld.gov.au. Archived from the original on 17 March 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- "Artist kept her people's culture and language alive.(News and Features)(Obituary)", The Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney, Australia), Fairfax Media Publications Pty Limited: 20, 7 September 2011, ISSN 0312-6315

- "Biography - Thancoupie Gloria Fletcher James - Indigenous Australia". ia.anu.edu.au. Archived from the original on 19 March 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- "Thancoupie (Thanakupi) the Potter (1937-2011)". Inside the collection - Powerhouse Museum. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2016.