The Abyss

The Abyss is a 1989 American science fiction film written and directed by James Cameron and starring Ed Harris, Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio, and Michael Biehn. When an American submarine sinks in the Caribbean, a US search and recovery team works with an oil platform crew, racing against Soviet vessels to recover the boat. Deep in the ocean, they encounter something unexpected.

| The Abyss | |

|---|---|

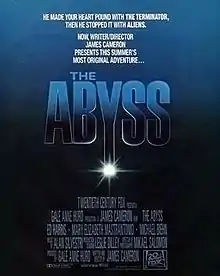

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | James Cameron |

| Written by | James Cameron |

| Produced by | Gale Anne Hurd |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Mikael Salomon |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Alan Silvestri |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox[1] |

Release date |

|

Running time | 140 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $43–47 million[nb 1] |

| Box office | $90 million[3] |

The film was released on August 9, 1989, receiving generally positive reviews and grossed $90 million. It was nominated for four Academy Awards and won the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects.

Plot

In January 1994, the U.S. Ohio-class submarine USS Montana has an encounter with an unidentified submerged object and sinks near the Cayman Trough. With Soviet ships moving in to try to salvage the sub and a hurricane moving over the area, the U.S. government sends a SEAL team to Deep Core, a privately owned experimental underwater drilling platform near the Cayman Trough, to use it as a base of operations. The platform's designer, Dr. Lindsey Brigman, insists on going along with the SEAL team, even though her estranged husband Virgil "Bud" Brigman is the current foreman.

During the initial investigation of Montana, a power cut in the team's submersibles leads to Lindsey seeing a strange light circling the sub, which she later calls a "non-terrestrial intelligence" or "NTI". Lt. Hiram Coffey, the SEAL team leader, is ordered to accelerate their mission and takes one of the mini-subs without Deep Core's permission to recover a Trident missile warhead from Montana just as the storm hits above, leaving the crew unable to disconnect from their surface support ship in time. The cable crane is torn from the ship and falls into the trench, dragging Deep Core to the edge before it stops. The rig is partially flooded, killing several crew members and damaging its power systems.

The crew waits out the storm so they can restore communications and be rescued. As they struggle against the cold, they find the NTIs have formed an animated column of water to explore the rig, which they equate to an alien version of a remotely operated vehicle. Though they treat it with curiosity, Coffey is agitated and cuts it in half by closing a pressure bulkhead on it, causing it to retreat. Realizing that Coffey is suffering paranoia from high-pressure nervous syndrome, the crew spies on him through an ROV, finding him and another SEAL arming the warhead to attack the NTIs. To try and stop him, Bud fights Coffey, but Coffey escapes in a mini-sub with the primed warhead. Bud and Lindsey give chase in the other sub, damaging both. Coffey is able to launch the warhead into the trench, but his sub drifts over the edge and implodes from the pressure, killing him. Bud's mini-sub is inoperable and taking on water. With only one functional diving suit, Lindsey opts to enter deep hypothermia and trigger her mammalian diving reflex when the ocean's cold water engulfs her. Bud swims back to the platform with her body; there, he and the crew use a defibrillator and administer CPR, and they manage to successfully revive her.

It is decided that the warhead needs to be disarmed, which is more than 2 miles (3.2 km) below them. One SEAL, Ensign Monk, helps Bud use an experimental diving suit equipped with a liquid breathing apparatus to survive to that depth, though he will only be able to communicate through a keypad on the suit. Bud begins his dive, assisted by Lindsey's voice to keep him coherent against the effects of the mounting pressure, and he reaches the warhead. Monk guides him in successfully disarming it. With little oxygen left in the system, Bud explains that he knew it was a one-way trip, and he tells Lindsey he loves her. As he waits for death, an NTI approaches Bud, takes his hand, and guides him to a massive alien city deep in the trench. Inside, the NTIs create an atmospheric pocket for Bud, allowing him to breathe normally. The NTIs then play back Bud's message to his wife and look at each other with understanding.

On Deep Core, the crew is waiting for rescue when they see a message from Bud that he met some friends and warns them to hold on. The base shakes, and lights from the trench herald the arrival of the alien ship. It rises to the ocean's surface, with Deep Core and several of the surface ships run aground on its hull. The crew of Deep Core exits the platform, surprised they are not dead from the sudden decompression. They see Bud walking out of the alien ship, and Lindsey races to hug him.

Special Edition

In the extended version, the events in the film are played against a backdrop of conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union, with the potential for all-out war. The sinking of Montana additionally fuels the aggression. There is additionally more conflict between Bud and Lindsey in regard to their former relationship. The primary addition is the ending: When Bud is taken to the alien ship, the aliens begin by showing him images of war and aggression from news sources around the globe. The aliens then create massive megatsunamis that threaten the world's coasts, but stop them short before they hit. Bud asks why they spared the humans, and they show Bud his message to Lindsey before bringing him, the alien ship, and Deep Core to the surface.

Cast

- Ed Harris as Virgil "Bud" Brigman, Deep Core's foreman and Lindsey's estranged husband.

- Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio as Dr. Lindsey Brigman, designer of the rig and Bud's estranged wife.

- Michael Biehn as US Navy SEAL Lieutenant Hiram Coffey, the commander of the Navy SEAL team.

- Leo Burmester as Catfish De Vries, a worker on the rig and a Vietnam veteran Marine who is skeptical of the SEALs.

- Todd Graff as Alan "Hippy" Carnes, a conspiracy theorist who believes that the NTIs have been covered up by the CIA.

- John Bedford Lloyd as "Jammer" Willis

- J.C. Quinn as Arliss "Sonny" Dawson

- Kimberly Scott as Lisa "One Night" Standing

- Captain "Kidd" Brewer Jr. as Lew Finler

- George Robert Klek as Wilhite, a US Navy SEAL

- Christopher Murphy as Schoenick, a US Navy SEAL

- Adam Nelson as Ensign Monk, a US Navy SEAL

- Chris Elliott as Bendix

- Richard Warlock as Dwight Perry

- Jimmie Ray Weeks as Leland McBride

- J. Kenneth Campbell as DeMarco

- William Wisher, Jr. as Bill Tyler, a reporter

- Ken Jenkins as Gerard Kirkhill

Production

H. G. Wells was the first to introduce the notion of a sea alien in his 1897 short story "In the Abyss".[4] The idea for The Abyss came to James Cameron when, at age 17 and in high school, he attended a science lecture about deep sea diving by a man, Francis J. Falejczyk, who was the first human to breathe fluid through his lungs in experiments conducted by Johannes A. Kylstra at Duke University.[5][6][7] He subsequently wrote a short story[8] that focused on a group of scientists in a laboratory at the bottom of the ocean. The basic idea did not change, but many of the details were modified over the years. Once Cameron arrived in Hollywood, he quickly realized that a group of scientists was not that commercial and changed it to a group of blue-collar workers.[9] While making Aliens, Cameron saw a National Geographic film about remote operated vehicles operating deep in the North Atlantic Ocean. These images reminded him of his short story.[7] He and producer Gale Anne Hurd decided that The Abyss would be their next film.[8] Cameron wrote a treatment combined with elements of a shooting script, which generated a lot of interest in Hollywood. He then wrote the script, basing the character of Lindsey on Hurd and finished it by the end of 1987.[8] Cameron and Hurd were married before The Abyss, separated during pre-production, and divorced in February 1989, two months after principal photography.[10]

Pre-production

The cast and crew trained for underwater diving for one week in the Cayman Islands.[11] This was necessary because 40% of all live-action principal photography took place underwater. Furthermore, Cameron's production company had to design and build experimental equipment and develop a state-of-the-art communications system that allowed the director to talk underwater to the actors and dialogue to be recorded directly onto tape for the first time.[12]

Cameron had originally planned to shoot on location in the Bahamas where the story was set but quickly realized that he needed to have a completely controlled environment because of the stunts and special visual effects involved.[12] He considered shooting the film in Malta, which had the largest unfiltered tank of water, but it was not adequate for Cameron's needs.[7] Underwater sequences for the film were shot at a unit of the Gaffney Studios, situated south of Cherokee Falls, outside Gaffney, South Carolina, which had been abandoned by Duke Power officials after previously spending $700 million constructing the Cherokee Nuclear Power Plant, along Owensby Street, Gaffney, South Carolina.[11]

Two specially constructed tanks were used. The first one, based on the abandoned plant's primary reactor containment vessel, held 7.5 million US gallons (28,000 m3) of water, was 55 feet (18 m) deep and 209 feet (70 m) across. At the time, it was the largest fresh-water filtered tank in the world. Additional scenes were shot in the second tank, an unused turbine pit, which held 2.5 million US gallons (9,500 m3) of water.[12] As the production crew rushed to finish painting the main tank, millions of gallons of water poured in and took five days to fill.[13] The Deepcore rig was anchored to a 90-ton concrete column at the bottom of the large tank. It consisted of six partial and complete modules that took over half a year to plan and build from scratch.[14]

Can-Dive Services Ltd., a Canadian commercial diving company that specialized in saturation diving systems and underwater technology, specially manufactured the two working craft (Flatbed and Cab One) for the film. Two million dollars was spent on set construction.[9]

Filming was also done at the largest underground lake in the world—a mine in Bonne Terre, Missouri, which was the background for several underwater shots.[15]

Principal photography

The main tank was not ready in time for the first day of principal photography. Cameron delayed filming for a week and pushed the smaller tank's schedule forward, demanding that it be ready weeks ahead of schedule.[13] Filming eventually began on August 15, 1988, but there were still problems. On the first day of shooting in the main water tank, it sprang a leak and 150,000 US gallons (570 m3) of water a minute rushed out.[8] The studio brought in dam-repair experts to seal it. In addition, enormous pipes with elbow fittings had been improperly installed. There was so much water pressure in them that the elbows blew off.[8]

Cameron's cinematographer, Mikael Salomon, used three cameras in watertight housings that were specially designed.[14] Another special housing was designed for scenes that went from above-water dialogue to below-water dialogue. The filmmakers had to figure out how to keep the water clear enough to shoot and dark enough to look realistic at 2,000 feet (700 m), which was achieved by floating a thick layer of plastic beads in the water and covering the top of the tank with an enormous tarpaulin.[14] Cameron wanted to see the actors' faces and hear their dialogue, and thus hired Western Space and Marine to engineer helmets which would remain optically clear underwater and installed state-of-the-art aircraft quality microphones into each helmet. Safety conditions were also a major factor with the installation of a decompression chamber on site, along with a diving bell and a safety diver for each actor.[14]

The breathing fluid used in the film actually exists but has only been thoroughly investigated in animals.[5] Over the previous 20 years it had been tested on several animals, who survived. The rat shown in the film was actually breathing fluid and survived unharmed.[10][16] Production consulted with Dr. Kylstra on the proper use of the breathing fluid for the film.[17] Ed Harris did not actually breathe the fluid. He held his breath inside a helmet full of liquid while being towed 30 feet (10 m) below the surface of the large tank. He recalled that the worst moments were being towed with fluid rushing up his nose and his eyes swelling up.[10]

Actors played their scenes at 33 feet (11 m), too shallow a depth for them to need decompression, and rarely stayed down for more than an hour at a time. Cameron and the 26-person underwater diving crew sank to 50 feet (17 m) and stayed down for five hours at a time. To avoid decompression sickness, they would have to hang from hoses halfway up the tank for as long as two hours, breathing pure oxygen.[10]

The cast and crew endured over six months of grueling six-day, 70-hour weeks on an isolated set. At one point, Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio had a physical and emotional breakdown on the set and on another occasion, Ed Harris burst into spontaneous sobbing while driving home. Cameron himself admitted, "I knew this was going to be a hard shoot, but even I had no idea just how hard. I don't ever want to go through this again".[9]

For example, for the scene where portions of the rig are flooded with water, he realized that he initially did not know how to minimize the sequence's inherent danger. It took him more than four hours to set up the shot safely.[10] Actor Leo Burmester said, "Shooting The Abyss has been the hardest thing I've ever done. Jim Cameron is the type of director who pushes you to the edge, but he doesn't make you do anything he wouldn't do himself."[11] A lightning storm caused a 200-foot (65 m) tear in the black tarpaulin covering the main tank.[13] Repairing it would have taken too much time, so the production began shooting at night.[18] In addition, blooming algae often reduced visibility to 20 feet (6 m) within hours. Over-chlorination led to divers' skin burning and exposed hair being stripped off or turning white.[18]

As production went on, the slow pace and daily mental and physical strain of filming began to wear on the cast and crew. Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio remembered, "We never started and finished any one scene in any one day".[10] At one point, Cameron told the actors to relieve themselves in their wetsuits to save time between takes.[18] While filming one of many takes of Mastrantonio's character's resuscitation scene—in which she was soaking wet, topless and repeatedly being slapped and pounded on the chest—the camera ran out of film, prompting Mastrantonio to storm off the set yelling, "We are not animals!"[19]

For some shots in the scene that focus on Ed Harris, he was yelling at thin air because Mastrantonio refused to film the scene again. Michael Biehn also grew frustrated by the waiting. He claimed that he was in South Carolina for five months and only acted for three to four weeks.[10] He remembered one day being ten meters underwater and "suddenly the lights went out. It was so black I couldn't see my hand. I couldn't surface. I realized I might not get out of there." Harris recalled: "One day we were all in our dressing rooms and people began throwing couches out the windows and smashing the walls. We just had to get our frustrations out."[6]

Cameron responded to these complaints, saying, "For every hour they spent trying to figure out what magazine to read, we spent an hour at the bottom of the tank breathing compressed air."[10] After 140 days and $4 million over budget, filming finally wrapped on December 8, 1988.[18] Before the film's release, there were reports from South Carolina that Ed Harris was so upset by the physical demands of the film and Cameron's dictatorial directing style that he said he would refuse to help promote the motion picture. Harris later denied this rumor and helped promote the film.[10] However, after its release and initial promotion, Harris publicly disowned the film, saying "I'm never talking about it and never will." Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio also disowned the film, saying, "The Abyss was a lot of things. Fun to make is not one of them."[20]

Post-production

To create the alien water tentacle, Cameron initially considered cel animation or a tentacle sculpted in clay and then animated via stop-motion techniques with water reflections projected onto it. Phil Tippett suggested Cameron contact Industrial Light & Magic.[13] The special visual effects work was divided up among seven FX divisions with motion control work by Dream Quest Images and computer graphics and opticals by ILM.[9] ILM designed a program to produce surface waves of differing sizes and kinetic properties for the pseudopod,[13] which was referred to by ILM informally as the "water weenie."[21] For the moment where it mimics Bud and Lindsey's faces, Ed Harris had eight of his facial expressions scanned while twelve of Mastrantonio's were scanned via software used to create computer-generated sculptures. The set was photographed from every angle and digitally recreated so that the pseudopod could be accurately composited into the live-action footage.[13] For the sequence where Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio touches the surface of the pseudopod, then-ILM receptionist Alia Agha stood in as a hand model.[21] The company spent six months to create 75 seconds of computer graphics needed for the creature. The film was to have opened on July 4, 1989, but its release was delayed for more than a month by production and special effects problems.[10] The animated sequences were supervised by ILM animation director Wes Takahashi.[22]

Studio executives were nervous about the film's commercial prospects when preview audiences laughed at scenes of serious intent. Industry insiders said that the release delay was because nervous executives ordered the film's ending completely re-shot. There was also the question of the size of the film's budget: 20th Century Fox stated that the budget was $43 million,[10] a figure Cameron himself has reiterated.[23] However, estimates put the figure higher with The New York Times estimating the cost at $45 million[24] and one executive claiming it cost $47 million,[25][26] while box office revenue tracker website The Numbers lists the production budget at $70 million.[27]

Reception

Box office

The Abyss was released on August 9, 1989, in 1,533 theaters, where it grossed $9.3 million on its opening weekend and ranked #2 at the box office behind Parenthood. It went on to make $54.2 million in North America and $35.5 million throughout the rest of the world for a worldwide total of $89.8 million.[3]

Critical response

On Rotten Tomatoes, a review aggregator, The Abyss has an 88% approval rating based on 48 reviews and an average rating of 7.30/10. The critical consensus states: "The utterly gorgeous special effects frequently overshadow the fact that The Abyss is also a totally gripping, claustrophobic thriller, complete with an interesting crew of characters."[28] On Metacritic, the film has an average score of 62 out of 100, based on 14 critics indicating "generally favorable reviews".[29] The reviews tallied therein are for both the theatrical release and the Special Edition. Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A-" on an A+ to F scale.[30]

David Ansen of Newsweek, summarizing the theatrical release, wrote, "The payoff to The Abyss is pretty damn silly — a portentous deus ex machina that leaves too many questions unanswered and evokes too many other films."[31] In her review for The New York Times, Caryn James wrote that the film had "at least four endings," and "by the time the last ending of this two-and-a-quarter-hour film comes along, the effect is like getting off a demon roller coaster that has kept racing several laps after you were ready to get off."[32] Chris Dafoe, in his review for The Globe and Mail, wrote, "At its best, The Abyss offers a harrowing, thrilling journey through inky waters and high tension. In the end, however, this torpedo turns out to be a dud—it swerves at the last minute, missing its target and exploding ineffectually in a flash of fantasy and fairy-tale schtick."[33] While praising the film's first two hours as "compelling", the Toronto Star remarked, "But when Cameron takes the adventure to the next step, deep into the heart of fantasy, it all becomes one great big deja boo. If we are to believe what Cameron finds way down there, E.T. didn't really phone home, he went surfing and fell off his board."[34] Mike Clark of USA Today gave the film three out of four stars and wrote, "Most of this underwater blockbuster is 'good,' and at least two action set pieces are great. But the dopey wrap-up sinks the rest 20,000 leagues."[35]

In her review for The Washington Post, Rita Kempley wrote that the film "asks us to believe that the drowned return to life, that the comatose come to the rescue, that driven women become doting wives, that Neptune cares about landlubbers. I'd sooner believe that Moby Dick could swim up the drainpipe."[36] Halliwell's Film Guide stated the film was, "despite some clever special effects, a tedious, overlong fantasy that is more excited by machinery than people."[37] Conversely, Peter Travers of Rolling Stone enthused, "[The Abyss is] the greatest underwater adventure ever filmed, the most consistently enthralling of the summer blockbusters…one of the best pictures of the year."[38] John Ferguson of Radio Times awarded it three stars out of five, stating "For some, this was James Cameron's Waterworld, a bloated, sentimental epic from the king of hi-tech thrillers. Some of the criticism was deserved, but it remains a fascinating folly, a spectacular and often thrilling voyage to the bottom of the sea [...] Cameron excels in cranking up the tension within the cramped quarters and the effects are awe-inspiring and deservedly won an Oscar. It's only marred by being overlong and by its sentimental attachment to aliens."[39]

The release of the Special Edition in 1993 garnered much praise. Each giving it thumbs up, Gene Siskel remarked, "The Abyss has been improved," and Roger Ebert added, "It makes the film seem more well rounded."[40] In the book Reel Views 2, James Berardinelli comments, "James Cameron's The Abyss may be the most extreme example of an available movie that demonstrates how the vision of a director, once fully realized on screen, can transform a good motion picture into a great one."[41]

Accolades

The Abyss won the 1990 Oscar for Best Visual Effects (John Bruno, Dennis Muren, Hoyt Yeatman, and Dennis Skotak). It was also nominated for:

- Best Art Direction (Art Direction: Leslie Dilley; Set Decoration: Anne Kuljian)

- Best Cinematography (Mikael Salomon)

- Best Sound (Don J. Bassman, Kevin F. Cleary, Richard Overton and Lee Orloff)[42]

Many other film organizations, such as the Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films, and the American Society of Cinematographers, also nominated The Abyss. The film ended up winning a total of three other awards from these organizations.[43]

Soundtrack

The soundtrack to The Abyss was written by Alan Silvestri and released by Varèse Sarabande on August 22, 1989.[44] In 2014, they issued a limited-edition (3,000 copies), two-disc album featuring the complete score minus the end credits medley, which is absent from both releases.

Special Edition

Rumors circulated from the film's opening weeks of sequences cut from the film's third act. Pressure to cut the film's running time stemmed from both distribution concerns and Industrial Light & Magic's then-inability to complete the required sequences. The looming three-hour length also limited the number of times the film could be shown each day, though Dances with Wolves would challenge industry notions. Test audience screenings revealed mixed reactions to the sequences as they appeared in their unfinished form.

Cameron held final cut provided that the film met a running time of roughly two hours and 15 minutes. He later noted, "Ironically, the studio brass were horrified when I said I was cutting the wave."[45]

What emerges in the winnowing process is only the best stuff. And I think the overall caliber of the film is improved by that. I cut only two minutes of Terminator. On Aliens, we took out much more. I even reconstituted some of that in a special (TV) release version. The sense of something being missing on Aliens was greater for me than on The Abyss, where the film just got consistently better as the cut got along. The film must function as a dramatic, organic whole. When I cut the film together, things that read well on paper, on a conceptual level, didn't necessarily translate to the screen as well. I felt I was losing something by breaking my focus. Breaking the story's focus and coming off the main characters was a far greater detriment to the film than what was gained. The film keeps the same message intact at a thematic level, not at a really overt level, by working in a symbolic way.[46]

Cameron elected to remove the wave sequences along with other, shorter scenes elsewhere in the film, reducing the running time from roughly two hours and 50 minutes to two hours and 20 minutes and diminishing his signature themes of nuclear peril and disarmament. Subsequent test audience screenings drew substantially better reactions.

Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio publicly expressed regret about some of the scenes selected for removal from the film's theatrical cut: "There were some beautiful scenes that were taken out. I just wish we hadn't shot so much that isn't in the film."[46]

Shortly after the film's premiere, Cameron and video editor Ed Marsh created a longer video cut of The Abyss for their own use that incorporated dailies. With the tremendous success of Cameron's Terminator 2: Judgment Day in 1991, Lightstorm Entertainment secured a five-year, $500 million financing deal with 20th Century Fox for films produced, directed or written by Cameron.[47] The contract allocated roughly $500,000 of the amount to complete The Abyss.[48] ILM was commissioned to finish the work they had started three years earlier, with many of the same people who had worked on it originally.

The CGI tools developed for Terminator 2: Judgment Day allowed ILM to complete the tidal wave sequence, as well as correcting flaws in rendering for all their other work done for the film.

The tidal wave sequence had originally been designed by ILM as a physical effect, using a plastic wave, but Cameron was dissatisfied with the end result, and the sequence was scrapped. By the time Cameron was ready to revisit The Abyss, ILM's CGI prowess had finally progressed to an appropriate level, and the wave was rendered as a CGI effect. Terminator 2: Judgment Day screenwriter and frequent Cameron collaborator William Wisher had a cameo in the scene as a reporter in Santa Monica who catches the first tidal wave on camera.

When it was discovered that original production sound recordings had been lost, new dialogue and foley were recorded, but since Kidd Brewer had died[49] before he could return to re-loop his dialog, producers and editors had to lift his original dialogue tracks from the remaining optical-sound prints of the dailies. The Special Edition was therefore dedicated to his memory as a result.

As Alan Silvestri was not available to compose new music for the restored scenes, Robert Garrett, who had composed temporary music for the film's initial cutting in 1989, was chosen to create new music. The Special Edition was completed in December 1992, with 28 minutes added to the film, and saw a limited theatrical release in New York City and Los Angeles on February 26, 1993, and expanded to key cities nationwide in the following weeks. Both versions of the film continue to receive public exhibitions, including a screening of an original 35mm print of the theatrical cut on August 20, 2019, in New York City.[50][51]

Home media

The first THX-certified LaserDisc title of the Special Edition Box Set was released in April 1993, in both widescreen and full-screen formats,[52] and it was a best-seller for the rest of the year. The Special Edition was released on VHS on August 20, 1996, as a part of Fox Video's Widescreen Series, with a seven-minute behind-the-scenes featurette with footage that did not appear in the Under Pressure: The Making of The Abyss documentary that was included on the Laserdisc and DVD releases.[53][54] The film was released on DVD in 2000 in both one- and two-disc editions and featured animated menus;[55] additionally, it featured both the theatrical and Special Edition versions of the film via seamless branching along with—on the second disc—the Laserdisc's extensive text, artwork and photographic documentation of the film's production, a ten-minute featurette, and the sixty-minute documentary Under Pressure: The Making of The Abyss.[56]

In 2014, the pay cable channels Cinemax and HBO began broadcasting both versions of the film in 1080p.[57][58] Netflix's UK service began offering the theatrical version in 1080p in 2017.[59] At an October, 2014 event James Cameron and Gale Anne Hurd were asked about a future Blu-ray release for the film. Cameron gestured to the head of Fox Home Entertainment, implying the decision lay with the studio.[60] Five months later, another article suggested a spat between Cameron and 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment was responsible for the delay.[61] While promoting the upcoming 30th-anniversary Blu-ray release of Aliens at Comic-Con in San Diego in July 2016, James Cameron confirmed that he was working on a remastered 4K transfer of The Abyss and that it would be released on Blu-ray for the first time in early 2017. Cameron added, "We've done a wet-gate 4K scan of the original negative, and it's going to look insanely good. We're going to do an authoring pass in the DI for Blu-ray and HDR at the same time."[62]

In March 2019, digital intermediate colorist Skip Kimball posted a photo to his Instagram suggesting that he was working on the film. In November 2018, Cameron told Empire magazine that a Blu-ray transfer was "complete for my review" and he hoped it would be ready before 2019.[63]

In December 2021, during a promotional interview for the new book Tech Noir: The Art of James Cameron with website Space.com, director Cameron made the following statement: "Yeah, we finished the transfer and I wanted to do it myself because Mikael [Salomon] did such a beautiful job with the cinematography on that film. It is truly, truly gorgeous cinematography. That was before I started to assert myself in terms of lighting and asking the cinematographer to do certain things. I'd compose with the camera and choose the lenses, but I left the lighting to him. He did a remarkable job on that movie that I appreciate better now than I did even as we were making it ... So I just recently finished the high-def transfer a couple of months ago[,] so presumably there’ll be Blu-rays and it will stream with a proper transfer from now on. I appreciate what you said about the film. It didn't make much money in its day, but it does seem to be well-liked over time."[64]

In December 2022, journalist Arthur Cios tweeted that, during an interview for Avatar: The Way of Water, he ask Cameron about a 4K release of The Abyss and that Cameron had told him "he had a new master and it would be out by March 2023 max."[65][66] However, Cameron conceded in January 2023 that a 4K release would be pushed back to the "second half of 2023" alongside True Lies.[67] Cameron premiered the completed 4K remaster at Beyond Fest in September 2023 and said new home video releases were coming in "a couple of months".[68]

Adaptations

American science fiction author Orson Scott Card was hired to write a novelization of the film based on the screenplay and discussions with Cameron.[69] He wrote back-stories for Bud, Lindsey, and Coffey as a means not only of helping the actors define their roles, but also to justify some of their behavior and mannerisms in the film. Card also wrote the aliens as a colonizing species which preferentially sought high-pressure deep-water worlds to build their ships as they traveled further into the galaxy (their mothership was in orbit on the far side of the Moon). The NTIs' knowledge of neuroanatomy and nanoscale manipulation of biochemistry was responsible for many aspects of the film.

A licensed interactive fiction video game based on the script was being developed for Infocom by Bob Bates, but was cancelled when Infocom was shut down by its then-parent company Activision.[70] Sound Source Interactive later released an action video game in 1998 entitled The Abyss: Incident at Europa. The game takes place a few years after the film, where the player must find a cure for a deadly virus.[71]

A two-issue comic book adaptation was published by Dark Horse Comics.[72]

Notes

- 20th Century Fox put the official budget of The Abyss (1989) at $43 million; however, other estimates place the true cost in the $45–47 million range, while box office revenue tracker website The Numbers estimated it cost $70 million.

See also

- Project Azorian – 1974 CIA project to recover the sunken Soviet submarine K-129

- List of underwater science fiction works

- List of films featuring the United States Navy SEALs

- The Kraken Wakes – 1953 science fiction novel by John Wyndham, features deep sea alien activity, albeit in a hostile capacity.

References

- "The Abyss". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Archived from the original on September 7, 2017. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

- "THE ABYSS (12)". British Board of Film Classification. October 17, 1989. Archived from the original on March 17, 2014. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- "The Abyss (1989)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on March 3, 2009.

- Renzi, Thomas C. (2004). H.G. Wells: Six Scientific Romances Adapted for Film (2nd ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. pp. 190–191. ISBN 978-0-81084-989-1.

- Kylstra, Johannes A. (February 28, 1977). The Feasibility of Liquid Breathing in Man (PDF) (Report). Vol. Report to the Office of Naval Research. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved April 29, 2015.

- McLean, Phillip (August 27, 1989). "Terror Strikes The Abyss". Sunday Mail.

- Smith (2001), p. 106.

- Walker, Beverly (August 9, 1989). "Film Plot Mirrored Filmmakers' Troubles". The Washington Times. p. E1.

- Blair (1989), p. 40.

- Harmetz, Aljean (August 6, 1989). "A Foray into Deep Waters". The New York Times. p. 15. Archived from the original on October 27, 2010. Retrieved August 14, 2009.

- Blair (1989), p. 38.

- Blair (1989), p. 39.

- Smith (2001), p. 107.

- Blair (1989), p. 58.

- "Bonne Terre Mine Tour". bonneterrebiz.com. Archived from the original on May 28, 2013.

- "A Response Rising Out of 'The Abyss'". Los Angeles Times. September 24, 1989. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- Shields, Meg (August 2, 2021). "How They Shot the Breathable Fluid Scenes in 'The Abyss'". Film School Rejects. Retrieved August 4, 2021.

- Smith (2001), p. 108.

- Hibberd, James (November 29, 2016). "Ed Harris discusses his 9 best movie roles". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on June 24, 2018. Retrieved June 23, 2018.

- "The Abyss Movie Trivia". The 80s Movies Rewind. Archived from the original on October 17, 2013.

- Hoare, James (August 5, 2022). "CGI Fridays: Matchmove Master Alia Agha Touched The Abyss". The Companion. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- "Subject: Wes Ford Takahashi". Animators' Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on August 12, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- Young James Cameron talks about Abyss, budgets, and his first job as a director (September 1989). YouTube. April 27, 2016. Event occurs at 3:54. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- Greenburg, James (May 26, 1991). "Film; Why the 'Hudson Hawk' Budget Soared So High". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 12, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- Sujo, Aly (August 8, 1989). "Abyss Puts Studio Executives on Edge". The Globe and Mail.

- "Long Swim". Los Angeles Times. July 16, 1989. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- "The Abyss (1989): Movie Details". The Numbers. Archived from the original on October 17, 2009. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- "The Abyss (1989)". Rotten Tomatoes. August 9, 1989. Archived from the original on July 5, 2010. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- "The Abyss". Metacritic. Archived from the original on May 1, 2011. Retrieved July 5, 2010.

- Hayden Mears (August 4, 2019). "James Cameron Has Only Made One 'Misstep' In His Career, According to Michael Biehn". CINEMABLEND. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

- Ansen, David (August 14, 1989). "Under Fire, Underwater". Newsweek. p. 56.

- James, Caryn (August 9, 1989). "Undersea Life and Peril". The New York Times. p. 13.

- Dafoe, Chris (August 9, 1989). "Big Leak in Underwater Adventure". The Globe and Mail.

- Toronto Star, October 9, 1989

- Clark, Mike (August 9, 1989). "The Abyss Gets in Deep - For Good and Bad". USA Today. p. 1D.

- Kempley, Rita (August 9, 1989). "Saturated Sci-Fi". Washington Post. p. C1.

- Halliwell's Film Guide (13th ed.). London, UK: HarperCollins. 1998. ISBN 0-00-638868-X.

- Travers, Peter (August 24, 1989). "The Abyss". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 30, 2008. Retrieved March 8, 2009.

- Ferguson, John. "The Abyss". Radio Times. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- Siskel & Ebert (June 8, 2012). "At The Movies - "The Abyss" released on Laserdisc". YouTube. Archived from the original on May 16, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- Berardinelli, James (2005). Reel Views 2: The Ultimate Guide to the Best 1,000 Modern Movies on DVD and Video. Boston, MA: Justin, Charles & Co. p. 582. ISBN 978-1-93211-240-5.

- "The 62nd Academy Awards (1990) Nominees and Winners". Oscars.org. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved August 1, 2011.

- "The Academy of Science Fiction Fantasy and Horror Films". Saturnawards.org. Archived from the original on November 7, 2015. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- Ankeny, Jason. "The Abyss [Original Score]". AllMusic. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved February 1, 2014.

- The Abyss Special Edition DVD, The Restoration

- Spelling, Ian (January 1990). "James Cameron: Filmmaker Under Pressure". Starlog. No. 150.

- Weinraub, Bernard (April 22, 1992). "Fox Locks In Cameron With a 5-Year Deal Worth $500 Million". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 15, 2018. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- The Toronto Star, Starweek Magazine

- "Kidd Brewer Jr. found dead at home". Wilmington Morning Star. May 24, 1990. Archived from the original on November 26, 2015. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- "The Abyss". IFC Center. August 20, 2019. Archived from the original on August 21, 2019. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- Seitz, Matt Zoller [@mattzollerseitz] (August 12, 2019). "New Yorkers: come see THE ABYSS (original theatrical cut) on 35mm …" (Tweet). Retrieved October 27, 2019 – via Twitter.

- Entertainment Tonight (April 1993). "The Abyss - Special Edition - Laserdisc Release". YouTube. Archived from the original on November 15, 2020. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- King, Susan (August 16, 1996). "'Letterbox' Brings Wide Screen Home". Times Staff Writer. Los Angeles Times. p. 96. Archived from the original on March 11, 2023. Retrieved March 11, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- "VHS Preview from "The Abyss: Special Edition" Widescreen Release". YouTube. 1996. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- "Opening To The Abyss 2000 DVD". YouTube. August 26, 2017. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- Wederquist, Robert (January 16, 2014). "The Abyss - Special Edition (1989)". Originaltrilogy.com. Archived from the original on April 6, 2018. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- "The Abyss on Max in HD 2.4 ratio". AVS Forum. May 4, 2014. Archived from the original on May 15, 2018. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- "Blu-ray Disc Releases : The Abyss Ever Going to Be Released?". Filmboards.com. July 20, 2015. Archived from the original on May 15, 2018. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- "The Abyss now on Netflix in HD". AV Forums.com. October 21, 2017. Archived from the original on January 1, 2019. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- Hunt, Bill (October 16, 2014). "Criterion's January Includes Sword Of Doom & More, Plus Majestic Stand-Alone Bd & Yet Another Abyss/True Lies Non-Update". TheDigitalBits.com. Archived from the original on May 15, 2018. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- Hunt, Bill (March 25, 2015). "1776: Director's Cut coming to BD, plus Strange Days: 20th (in Germany), a Giger documentary & Kubrick's Spartacus!". TheDigitalBits.com. Archived from the original on May 15, 2018. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- Tapley, Kristopher (July 23, 2016). "James Cameron On Why 'Avatar' Needs Three Sequels and Details on an 'Abyss' Blu-ray Release". Variety. Archived from the original on May 15, 2018. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- Evangelista, Chris (March 5, 2019). "Is 'The Abyss' Blu-ray Finally Being Released, and in 4K?". Empire. Archived from the original on November 16, 2019. Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- Spry, Jeff (December 18, 2021). "James Cameron recounts 50 years of cinematic art in lavish 'Tech Noir' book (exclusive)". space.com. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- @ArthurCios (December 10, 2022). "Vu que la question traîne beaucoup sur Twitter, j'ai voulu lui demander. Après, clairement, quand t'as que 9 minutes d'interview, c'est compliqué" (Tweet) (in French) – via Twitter.

- "James Cameron Hints at the Abyss Finally Getting 4K Release".

- Brew, Simon (January 23, 2023). "James Cameron reveals The Abyss and True Lies getting 4K disc releases this year". Film Stories. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- Gilchrist, Todd (September 28, 2023). "James Cameron Surprises Beyond Fest With 4K Premiere of 'The Abyss,' Recalls Nearly Dying During Filming: 'It Was Almost Check-Out Point'". Variety. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- "Books By Orson Scott Card - The Abyss". Hatrack River. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018. Retrieved January 16, 2018.

- Jong, Philip (February 12, 2001). "Bob Bates interview". Adventure Classic Gaming.com. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- "The Abyss: Incident at Europa for Windows (1998)". MobyGames. Archived from the original on December 19, 2012. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- "The Abyss". Archived from the original on April 30, 2021. Retrieved April 30, 2021.

Sources

External links

- The Abyss at IMDb

- The Abyss at AllMovie

- The Abyss at Box Office Mojo

- The Abyss at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Abyss at Metacritic

- Scott, Chris; Meyer, Austin (March 2003). "The Abyss (Set visit at Gaffney)". X-plane.com.

- Snyder, David (May 2001). "Abyss Trip (set pictures at Gaffney with both air and ground shots)". Snydersweb.com.

- Dare, Michael. "Life's Abyss and then You Die: An Interview with James Cameron". Movieline. Archived from the original on August 7, 2008. Retrieved October 27, 2019 – via Emulsional Problems.