Battle of Princeton

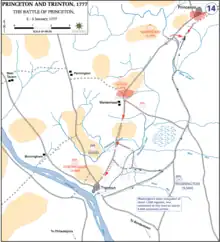

The Battle of Princeton was a battle of the American Revolutionary War, fought near Princeton, New Jersey on January 3, 1777, and ending in a small victory for the Colonials. General Lord Cornwallis had left 1,400 British troops under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Charles Mawhood in Princeton. Following a surprise attack at Trenton early in the morning of December 26, 1776, General George Washington of the Continental Army decided to attack the British in New Jersey before entering the winter quarters. On December 30, he crossed the Delaware River back into New Jersey. His troops followed on January 3, 1777. Washington advanced to Princeton by a back road, where he pushed back a smaller British force but had to retreat before Cornwallis arrived with reinforcements. The battles of Trenton and Princeton were a boost to the morale of the patriot cause, leading many recruits to join the Continental Army in the spring.

| Battle of Princeton | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the New York and New Jersey campaign | |||||||

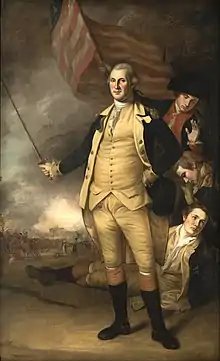

Washington Rallying the Americans at the Battle of Princeton by William Ranney (1848) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

4,500 35 guns[2] |

1,200 6–9 guns[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

25–44 killed 40 wounded[4][5] |

50–100 killed 58–70 wounded 194–280 captured[6][7] | ||||||

Location within USA Midwest and Northeast  Battle of Princeton (New Jersey) | |||||||

After defeating the Hessians at the Battle of Trenton on the morning of December 26, 1776, Washington withdrew back to Pennsylvania. He subsequently decided to attack the British forces before going into winter quarters. On December 29, he led his army back into Trenton. On the night of January 2, 1777, Washington repulsed a British attack at the Battle of the Assunpink Creek. That night, he evacuated his position, circled around General Cornwallis' army, and went to attack the British garrison at Princeton.

On January 3, Brigadier General Hugh Mercer of the Continental Army clashed with two regiments under the command of Mawhood. Mercer and his troops were overrun, and Mercer was mortally wounded. Washington sent a brigade of militia under Brigadier General John Cadwalader to help them. The militia, on seeing the flight of Mercer's men, also began to flee. Washington rode up with reinforcements and rallied the fleeing militia. He then led the attack on Mawhood's troops, driving them back. Mawhood gave the order to retreat, and most of the troops tried to flee to Cornwallis in Trenton.

In Princeton, Brigadier General John Sullivan encouraged some British troops who had taken refuge in Nassau Hall to surrender, ending the battle. After the battle, Washington moved his army to Morristown, and with their third defeat in 10 days, the British evacuated Central Jersey. The battle (while considered minor by British standards)[8][9] was the last major action of Washington's winter New Jersey campaign.

Background

Victories at Trenton

On the night of December 25–26, 1776, General George Washington, Commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, led 2,400 men across the Delaware River.[10] After a nine-mile march, they seized the town of Trenton on the morning of December 26, killing or wounding over 100 Hessians and capturing 900 more. Soon after capturing the town, Washington led the army back across the Delaware into Pennsylvania.[11] On December 29, Washington once again led the army across the river and established a defensive position at Trenton. On December 31, Washington appealed to his men, whose enlistments expired at the end of the year, "Stay for just six more weeks for an extra bounty of ten dollars." His appeal worked, and most of the men agreed to stay.[12] Also that day, Washington learned that Congress had voted to give him wide-ranging powers for six months that are often described as dictatorial.[13]

In response to the loss at Trenton, General Cornwallis left New York City and reassembled a British force of more than 9,000 at Princeton to oppose Washington. Leaving 1,200 men under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Mawhood at Princeton, Cornwallis left Princeton on January 2 in command of 8,000 men to attack Washington's army of 6,000 troops.[14] Washington sent troops to skirmish with the approaching British to delay their advance. It was almost nightfall by the time the British reached Trenton. After three failed attempts to cross the bridge over the Assunpink Creek, beyond which were the primary American defenses, Cornwallis called off the attack until the next day.[15]

Evacuation

During the night, Washington called a council of war and asked his officers whether they should stand and fight, attempt to cross the river somewhere, or take the back roads to attack Princeton. Although the idea had already occurred to Washington, he learned from Arthur St. Clair and John Cadwalader that his plan to attack Princeton was indeed possible. Two intelligence collection efforts, both of which came to fruition at the end of December 1776, supported such a surprise attack. After consulting with his officers, they agreed that the best option was to attack Princeton.[16]

Washington ordered that the excess baggage be taken to Burlington where it could be sent to Pennsylvania. The ground had frozen, making it possible to move the artillery without it sinking into the ground. By midnight, the plan was complete, with the baggage on its way to Burlington and the guns wrapped in heavy cloth to stifle noise and prevent the British from learning of the evacuation. Washington left 500 men behind with two cannon to patrol, keep the fires burning, and to work with picks and shovels to make the British think that they were digging in. Before dawn, these men were to join up with the main army.[17]

By 2:00 am, the entire army was in motion roughly along Quaker Bridge Road through what is now Hamilton Township. The men were ordered to march with silence. Along the way, a rumor was spread that they were surrounded, and some frightened militiamen fled for Philadelphia. The march was difficult, as some of the route ran through thick woods and it was icy, causing horses to slip and men to break through ice on ponds.[18]

Plan of attack

As dawn came, the army approached a stream called Stony Brook. The road the army took followed Stony Brook for a mile farther until it intersected the Post Road from Trenton to Princeton. However, off to the right of this road, there was an unused road which crossed the farmland of Thomas Clark. The road was not visible from the Post Road and ran through cleared land to a stretch from which the town could be entered at any point because the British had left it undefended.[19]

However, Washington was running behind schedule as he had planned to attack and capture the British outposts before dawn and capture the garrison shortly afterward. By the time dawn broke he was still two miles from the town. According to the standard account of the battle, Washington sent 350 men under the command of Brigadier General Hugh Mercer to destroy the bridge over Stony Brook in order to delay Cornwallis's army when he found out that Washington had escaped. According to a newer analysis, however, Brigadier General Thomas Mifflin was tasked with the bridge, and Mercer's forces did not break off from the main column until later.[20]

Shortly before 8:00 am, Washington wheeled the rest of the army to the right down the unused road. First in the column went General John Sullivan's division consisting of Arthur St. Clair's and Isaac Sherman's brigades. Following them were John Cadwalader's brigade and then Daniel Hitchcock's.[21]

Mawhood's reaction

Cornwallis had sent orders to Mawhood to bring the 17th and 55th British regiments to join his army in the morning. Mawhood had moved out from Princeton to fulfill these orders when his troops climbed the hill south of Stony Brook and sighted the main American army. Unable to figure out the size of the American army because of the wooded hills, he sent a rider to warn the 40th British Regiment, which he had left in Princeton, then wheeled the 17th and 55th Regiments around and headed back to Princeton. That day, Mawhood had called off the patrol which was to reconnoiter the area from which Washington was approaching.[22]

Mercer received word that Mawhood was leading his troops back to Princeton.[23] Mercer, on orders from Washington, moved his column to the right in order to hit the British before they could confront Washington's main army.[24] Mercer moved towards Mawhood's rear, but when he realized he would not be able to cut off Mawhood in time, he decided to join Sullivan. When Mawhood learned that Mercer was in his rear and moving to join Sullivan, Mawhood detached part of the 55th Regiment to join the 40th Regiment in the town and then moved the rest of the 55th, the 17th, fifty cavalry, and two artillery pieces to attack Mercer.[25]

Battle

Mawhood overruns Mercer

Mawhood ordered his light troops to delay Mercer, while he brought up the other detachments. Mercer was walking through William Clark's orchard when the British light troops appeared. The British light troops' volley went high, which gave time for Mercer to wheel his troops around into battle line. Mercer's troops advanced, pushing back the British light troops. The Americans took up a position behind a fence at the upper end of the orchard. However, Mawhood had brought up his troops and his artillery.[26] The American gunners opened fire first, and for about ten minutes, the outnumbered American infantry exchanged fire with the British. However, many of the Americans had rifles which took longer to load than muskets. Mawhood ordered a bayonet charge, and because many of the Americans had rifles, which could not be equipped with bayonets, they were overrun.[27] Both of the Americans' cannon were captured, and the British turned them on the fleeing troops. Mercer was surrounded by British soldiers, and they shouted at him "Surrender, you damn rebel!" Declining to ask for quarter, Mercer chose to resist instead. The British, thinking they had caught Washington, bayoneted him and then left him for dead. Mercer's second in command, Colonel John Haslet, was shot through the head and killed.[28]

Cadwalader's arrival

Fifty light infantrymen were in pursuit of Mercer's men when a fresh brigade of 1,100 militiamen under the command of Cadwalader appeared.[29] Mawhood gathered his men who were all over the battlefield and put them into battle line formation. Meanwhile, Sullivan was at a standoff with the detachment of the 55th Regiment that had come to assist the 40th Regiment, neither daring to move towards the main battle for risk of exposing its flank. Cadwalader attempted to move his men into a battle line, but they had no combat experience and did not know even the most basic military maneuvers. When his men reached the top of the hill and saw Mercer's men fleeing from the British, most of the militia turned around and ran back down the hill.[30]

Washington's arrival

As Cadwalader's men began to flee, the American guns opened fire onto the British, who were preparing to attack, and the guns were able to hold them off for several minutes. Cadwalader was able to get one company to fire a volley but it fled immediately afterwards. At this point, Washington arrived with the Virginia Continentals and Edward Hand's riflemen.[31] Washington ordered the riflemen and the Virginians to take up a position on the right hand side of the hill, and then Washington quickly rode over to Cadwalader's fleeing men. Washington shouted, "Parade with us my brave fellows! There is but a handful of the enemy and we shall have them directly!".[32] Cadwalader's men formed into battle formation at Washington's direction. When Daniel Hitchcock's New England Continentals arrived, Washington sent them to the right, where he had put the riflemen and the Virginians.[33]

Washington, with his hat in his hand, rode forward and waved the Americans forward. At this point, Mawhood had moved his troops slightly to the left to get out of the range of the American artillery fire. Washington gave orders not to fire until he gave them the signal, and when they were thirty yards away, he turned around on his horse, facing his men and said "Halt!" and then "Fire!".[34] At this moment, the British also fired, obscuring the field in a cloud of smoke. One of Washington's officers, John Fitzgerald, pulled his hat over his eyes to avoid seeing Washington killed, but when the smoke cleared, Washington appeared, unharmed, waving his men forward.[35]

British collapse

On the right, Hitchcock's New Englanders fired a volley and then advanced again, threatening to turn the British flank.[36] The riflemen were slowly picking off British soldiers while the American artillery was firing grapeshot at the British lines. At this point, Hitchcock ordered his men to charge, and the British began to flee. The British attempted to save their artillery, but the militia also charged, and Mawhood gave the order to retreat. The British fled towards the Post Road followed by the Americans. Washington reportedly shouted, "It's a fine fox chase my boys!" Some Americans had swarmed onto the Post Road in order to block a British retreat across the bridge, but Mawhood ordered a bayonet charge and broke through the American lines, escaping across the bridge. Some of the Americans, Hand's riflemen among them, continued to pursue the British, and Mawhood ordered his dragoons to buy them some time to retreat; however, the dragoons were pushed back. Some Americans continued to pursue the fleeing British until nightfall, killing some and taking some prisoners.[37] After some time, Washington turned around and rode back to Princeton.[38]

At the edge of town, the 55th Regiment received orders from Mawhood to fall back and join the 40th Regiment in town. The 40th had taken up a position just outside town, on the north side of a ravine. The 55th formed up to the left of the 40th. The 55th sent a platoon to flank the oncoming Americans, but it was cut to pieces. When Sullivan sent several regiments to scale the ravine, they fell back to a breastwork. After making a brief stand, the British fell back again, some leaving Princeton and others taking up refuge in Nassau Hall.[39] Alexander Hamilton brought three cannons up and had them blast away at the building. Then some Americans rushed the front door, broke it down, and the British put a white flag outside one of the windows. 194 British soldiers walked out of the building and laid down their arms.[40]

Aftermath

After entering Princeton, the Americans began to loot the abandoned British supply wagons and the town.[41] With news that Cornwallis was approaching, Washington knew he had to leave Princeton. Washington wanted to push on to New Brunswick and capture a British pay chest of 70,000 pounds, but Major Generals Henry Knox and Nathanael Greene talked him out of it.[42] Instead, Washington moved his army to Somerset Courthouse on the night of January 3, then marched to Pluckemin by January 5, and arrived at Morristown by sunset the next day for winter encampment.[43][44] After the battle, Cornwallis abandoned many of his posts in New Jersey and ordered his army to retreat to New Brunswick. The next several months of the war consisted of a series of small scale skirmishes known as the Forage War.

Casualties

General Howe's official casualty report for the battle stated 18 killed, 58 wounded and 200 missing.[45] Mark Boatner says that the Americans took 194 prisoners during the battle, while the remaining 6 "missing" men may have been killed.[46] A civilian eyewitness (the anonymous writer of A Brief Narrative of the Ravages of the British and Hessians at Princeton in 1776–1777) wrote that 24 British soldiers were found dead on the field. Washington claimed that the British had more than 100 killed and 300 captured.[47] William S. Stryker follows Washington in stating that the British loss was 100 men killed, 70 wounded and 280 captured.[48]

Washington reported his own army's casualties as 6 or 7 officers and 25 to 30 enlisted men killed, giving no figures for the wounded.[49] Richard M. Ketchum states that the Americans had "30 enlisted men and 14 officers killed";[50] Henry B. Dawson gives 10 officers and 30 enlisted men killed;[51] while Edward G. Lengel gives total casualties as 25 killed and 40 wounded.[52] The Loyalist newspaper, New York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, reported on January 17, 1777, that the American losses at Princeton had been 400 killed and wounded.[53]

The colonnade on the Princetown Battlefield Monument marks the common grave of 15 Americans and 21 British killed.[54] In addition, one British officer, Captain William Leslie, died of his wounds and was buried at Pluckemin, New Jersey.[55][56]

Consequences

The British viewed Trenton and Princeton as minor American victories, but with these victories, the Americans believed that they could win the war.[57] American historians often consider the Battle of Princeton a great victory, on par with the battle of Trenton, because of the subsequent loss of control of most of New Jersey by the Crown forces. Some other historians, such as Edward Lengel, consider it to be even more impressive than Trenton.[58] A century later, British historian Sir George Otto Trevelyan wrote in a study of the American Revolution, when talking about the impact of the victories at Trenton and Princeton, that "It may be doubted whether so small a number of men ever employed so short a space of time with greater and more lasting effects upon the history of the world."[59]

Legacy

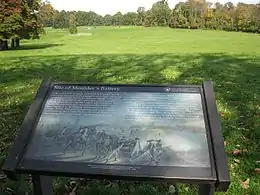

Part of the battlefield is now preserved in Princeton Battlefield State Park, which was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1961.[60] Another section of the battlefield adjacent to the state park was embroiled in a development controversy. The Institute for Advanced Study, which owns the property, had planned a housing project on land where George Washington charged with his men during the battle.[61] Historians, the Department of the Interior and archaeological evidence confirm the land's significance.[62] Several national and local preservation organizations worked to prevent construction on the property, and the Princeton Battlefield Society had legal action pending as of summer 2016.[63] On December 12, 2016, the American Battlefield Trust) announced that through its Campaign 1776 project to preserve land at battlefields of the Revolutionary War and War of 1812, it had reached an agreement to purchase almost 15 acres of land from the Institute for Advanced Study valued at $4.1 million. This purchase would increase the size of the state park by 16%. Seven of the planned single family dwellings would be replaced with townhouses and a total of 16 housing units would be constructed. The compromise arrangement was subject to approval by the Princeton Planning Board and Delaware and Raritan Canal Commission.[64] The Trust had already acquired and preserved nine other acres of the Princeton battlefield.[65] On May 30, 2018, the Trust announced that it had finalized the purchase after raising almost $3.2 million from private donors, which was matched by an $837,000 grant from the National Park Service and the Mercer County Open Space Assistance Program. The completed purchase ended the long dispute over how and whether the battlefield land would be developed.[66] As of mid-2023, the Trust and its partners had preserved more than 24 acres of the battlefield.[67]

The equestrian statue of George Washington at Washington Circle in Washington, D.C. depicts him at the Battle of Princeton. Sculptor Clark Mills said in his speech at the statue's dedication ceremony on February 22, 1860, "The incident selected for representation of this statue was at the battle of Princeton where Washington, after several ineffectual attempts to rally his troops, advanced so near the enemy's lines that his horse refused to go further, but stood and trembled while the brave rider sat undaunted with reins in hand. But while his noble horse is represented thus terror stricken, the dauntless hero is calm and dignified, ever believing himself the instrument in the hand of Providence to work out the great problem of liberty."[68]

Eight current Army National Guard units (101st Eng Bn,[69] 103rd Eng Bn,[70] A/1-104th Cav,[71] 111th Inf,[72] 125th QM Co,[73] 175th Inf,[74] 181st Inf[75] and 198th Sig Bn[76]) and one currently-active Regular Army Artillery battalion (1–5th FA[77] ) are derived from American units that participated in the Battle of Princeton. There are thirty current units of the U.S. Army with colonial roots.

A famous story, possibly apocryphal, states that during the Battle of Princeton, Alexander Hamilton ordered his cannon to fire upon the British soldiers taking refuge in Nassau Hall. As a result, one of the cannonballs was shot through the head of the portrait of King George II that hung in the chapel, which was subsequently replaced with a portrait of George Washington.[78] Tangentially, a few years earlier Hamilton had been refused accelerated study at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) housed in Nassau Hall. He attended King's College (now Columbia University) in New York, instead.

See also

- New Jersey in the American Revolution

- American Revolutionary War §British New York counter-offensive. The 'Battle of Princeton' placed in overall sequence and strategic context.

- The Death of General Mercer at the Battle of Princeton, January 3, 1777

Footnotes

- Newton, 2011, pp. 47–48

- Fischer, 2006, p. 404

- Fischer, 2006, p. 404

- Lengel, 2005, p. 208

- Ketchum, 1999, p. 373

- Stryker, 1898, pp. 308–309

- Boatner, 1966, p. 893

- "Battle of Princeton" Xtimeline

- "Battle of Princeton" TotallyHistory

- McCullough, 2006, p. 276

- McCullough, 2006, p. 281

- Ketchum, 1999, p. 278

- McCullough, 2006, p. 286

- Fischer, 2006, p. 404

- Lengel, 2005, pp. 199–200

- Ketchum, 1999, pp. 293–294

- Ketchum, 1999, p. 295

- Ketchum, 1999, pp. 295–296

- Ketchum, 1999, p. 297

- Robert A. Selig, Matthew Harris, and Wade P. Catts (September 2010). Battle of Princeton Mapping Project: Report of Military Terrain Analysis and Battle Narrative (PDF) (Report). Princeton Battlefield Society. Retrieved April 27, 2023.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ketchum, 1999, pp. 297–298

- Ketchum, 1999, pp. 298–299

- Ketchum, 1999, p. 299

- Lengel, 2005, p. 202

- Ketchum, 1999, pp. 299–300

- Ketchum, 1999, pp. 300–301

- Fischer, 2006, p. 404

- Ketchum, 1999, pp. 303–304

- Lengel, 2005, p. 204

- Ketchum, 1999, pp. 304–305

- Ketchum, 1999, pp. 306–307

- McCullough, 2006, p. 289

- Ketchum, 1999, p. 307

- Ketchum, 1999, pp. 307–308

- Ketchum, 1999, p. 362

- Ketchum, 1999, pp. 361–364

- Ketchum, 1999, p. 300

- Ketchum, 1999, pp. 361–364

- Fischer, 2006, pp. 338–339

- Ketchum, 1999, pp. 361–364

- Lengel, 2005, p. 206

- McCullough, 2006, p. 290

- Lengel, 2005, p. 208

- Fischer, 2006, p. 342

- Rosenfeld, 2005

- Boatner, 1966, p. 893

- Collins, 1968, pp. 33–34

- Stryker, 1898, pp. 308–309

- Freeman, 1951, p. 360

- Ketchum, 1999, p. 373

- Dawson, 1860, Vol. I, p. 208

- Lengel, 2005, p. 208

- Collins, 1968, p. 19

- "Princeton Battlefield State Park" NJ Parks

- Rodney, 1776–1777, pp. 39–40

- Ashton, 1982 "Pluckenmin Village"

- McCullough, 2006, p. 290

- Lengel, 2005, p. 208

- McCullough, 2006, p. 291

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "Preserve-don't destroy" NJ.com editorial

- Lender, 2016 "The new battle of Princeton"

- "Princeton: Nine-member coalition urges Institute for Advanced Study to reconsider faculty housing project". The Princeton Packet.

- "Institute for Advanced Study and Civil War Trust Announce Agreement to Expand the Princeton Battlefield State Park While Meeting Institute Housing Needs". Institute for Advanced Study. December 12, 2016. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- American Battlefield Trust "Saved Land" webpage. Accessed Jan. 19, 2018.

- Planet Princeton, May 30, 2018, "Institute for Advanced Study and American Battlefield Trust finalize deal that enlarges Princeton Battlefield Park." Accessed June 4, 2018.

- "Princeton Battlefield". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved June 19, 2023.

- "The Concluding Scenes of the 22d," The Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), February 22, 1860, p. 3

- Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 101st Engineer Battalion

- Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 103rd Engineer Battalion.

- Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, Troop A/1st Squadron/104th Cavalry.

- Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 111th Infantry. Reproduced in Sawicki 1981. pp. 217–219.

- Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 125th Quartermaster Company Archived 2014-12-18 at the Wayback Machine.

- Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 175th Infantry. Reproduced in Sawicki 1982, pp. 343–345.

- Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 181st Infantry. Reproduced in Sawicki 1981, pp. 354–355.

- Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 198th Signal Battalion.

- Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 1st Battalion, 5th Field Artillery.

- Linke, Dan (January 24, 2008). "Alexander Hamilton shooting the cannonball that destroys the portrait of King George". Princeton University: Mudd Manuscript Library Blog. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

References

- Ashton, Charles H. (July 26, 1982). "NRHP Nomination: Pluckemin Village Historic District". National Park Service. p. 17.

- Boatner, Mark Mayo (1966). Cassell's Biographical Dictionary of the American War of Independence 1763–1783. London: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-29296-6.

- Collins, Varnum Lansing, ed. (1968). A Brief Narrative of the Ravages of the British and Hessians at Princeton in 1776–1777. New York: The New York Times and Arno Press. OCLC 712635.

- Dawson, Henry B. (1860). Battles of the United States by Sea and Land. New York: Johnson, Fry and Company.

- Fischer, David Hackett (2006). Washington's Crossing. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-518159-X.

- Freeman, Douglas Southall (1951). George Washington: A Biography. Volume Four: Leader of the Revolution. London: Eyre & Spottiswood. ASIN B00G9PCAV2.

- Ketchum, Richard (1999). The Winter Soldiers: The Battles for Trenton and Princeton. Holt Paperbacks; 1st Owl books ed edition. ISBN 0-8050-6098-7.

- Lender, Mark Edward (July 6, 2016). "Commentary: The new battle of Princeton". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- Lengel, Edward (2005). General George Washington. New York: Random House Paperbacks. ISBN 0-8129-6950-2.

- Lowell, Edward J. (1884). The Hessians and the other German Auxiliaries of Great Britain in the Revolutionary War. New York: Harper Brothers Publishers.

- McCullough, David (2006). 1776. New York: Simon and Schuster Paperback. ISBN 0-7432-2672-0.

- Newton, Michael E. (2011). Angry Mobs and Founding Fathers: The Fight for Control of the American Revolution. Michael Newton. ISBN 978-0-9826040-2-1. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- Rodney, Thomas (1776–1777). Diary of Captain Thomas Rodney. Historical Society of Delaware. pp. 39–40.

- Rosenfeld, Ross (January 2005). "Battle of Princeton". HistoryNet. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- Sawicki, James A. (1981). Infantry Regiments of the US Army. Dumfries, VA: Wyvern Publications. ISBN 978-0-9602404-3-2.

- Stryker, William S. (1898). The Battles of Trenton and Princeton. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company.

Online articles without authors

- "Battle of Princeton". Totallyhistory. January 24, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- Chuckee (ed.). "Battle of Princeton boosts morale". Archived from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

- "Princeton Battlefield State Park". New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, Division of Parks and Forestry. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- "Preserve – don't destroy – piece of Princeton Battlefield". NJ.com:True Jersey. January 16, 2019. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

Further reading

- Bonk, David (2009). Trenton and Princeton 1776–77: Washington crosses the Delaware. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1846033506.

- Lowell, Edward J. (1884). The Hessians and the other German Auxiliaries of Great Britain in the Revolutionary War. New York: Harper Brothers Publishers.

- Maloy, Mark. Victory or Death: The Battles of Trenton and Princeton, December 25, 1776 – January 3, 1777. Emerging Revolutionary War Series. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2018. ISBN 978-1-61121-381-2.

- Smith, Samuel Stelle (2009) [1967]. The Battle of Trenton/The Battle of Princeton: Two Studies. Westholme Publishing. ISBN 978-1594160912.

External links

- Battle of Princeton

- Princeton Battlefield State Park official site

- Virtual Tour of the park

- "The Winter Patriots: The Trenton-Princeton Campaign of 1776–1777". George Washington's Mount Vernon.

- Animated History Map of the Battle of Princeton Archived 2012-10-09 at the Wayback Machine