The Diving Bell and the Butterfly

The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (original French title: Le Scaphandre et le Papillon) is a memoir by journalist Jean-Dominique Bauby. It describes his life before and after a massive stroke left him with locked-in syndrome.

| |

| Author | Jean-Dominique Bauby |

|---|---|

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

| Genre | Autobiography, Memoir |

| Publisher | Éditions Robert Laffont |

Publication date | March 6, 1997 |

| ISBN | 978-0-375-40115-2 |

The French edition of the book was published on March 7, 1997. It sold the first 25,000 copies on the day of publication, reaching 150,000 in a week. It went on to become a number one bestseller across Europe. Its total sales are now in the millions.

Plot summary

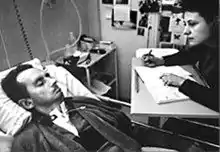

On December 8, 1995, Bauby, the editor-in-chief of French Elle magazine, suffered a stroke and lapsed into a coma. He awoke 20 days later, mentally aware of his surroundings, but physically paralyzed with what is known as locked-in syndrome, with the only exception of some movement in his head and eyes. Further, his right eye had to be sewn up because of irritation. Bauby wrote the entire book by blinking his left eyelid, which took him two months working 3 hours a day, 7 days a week.[1] Using partner assisted scanning, a transcriber repeatedly recited a French language frequency-ordered alphabet (E, S, A, R, I, N, T, U, L, etc.), until Bauby blinked to choose the next letter. The book took Bauby about 200,000 blinks to write at an average of approximately two minutes per word. The book also chronicles everyday events for a person with locked-in syndrome. These events include playing at the beach with his family, getting a bath, and meeting visitors while in hospital at Berck-sur-Mer. On March 9, 1997, two days after the book was published, Bauby died of pneumonia.[2][3]

Chapters

- Prologue: Jean-Dominique Bauby begins by detailing his rousing in room 119 at the Maritime Hospital at Berck the morning a year after the stroke that led to his locked-in syndrome. He recalls the days that followed and the resulting limitations: paralysis and blinking in his left eyelid. His mind is active, and he prepares for the publisher's emissary's arrival, though his thoughts are interrupted by a nurse.

- The Wheelchair: He is visited by many medical professionals. His situation hasn't fully sunk in and he does not fully understand the connotation of the wheelchair. It isn't until a comment is made by the occupational therapist that it becomes clear to him.

- Prayer: There are only 2 patients at Berck that have locked-in syndrome. His case is unique in that he maintains the ability to turn his head. He hopes to improve his respiration and regain his ability to eat without a gastric tube; as well as possibly be able to speak again. His friends and family have dedicated all kinds of religions and spiritual deities to his recovery, and he has assigned specific parts of his body to some too.

- Bathtime: His physical therapist arrives for the exercise, “mobilization,” where his limbs are moved. He has lost 27 kg (60 pounds) in twenty weeks. He notes that he has more mobilization in his head as he can rotate it 90 degrees. He recounts that even with limited facial expression, he still has varying emotions each time he is cleaned or given a bath.

- The Alphabet: He describes the creation, use, and precision of the alphabet he uses to communicate. ESARINTULOMDPCFB VHGJQZYXKW. He ordered the letters from the most common to the least in the French language. His visitors read the alphabet, and when he hears the letter he wishes for them to write down, he blinks his left eye, a method not without its challenges.

- The Empress: Empress Eugenie, wife of Napoleon III, was the patroness of the hospital, which contains various depictions of her. He tells of an imperial visit on May 4, 1864, where he imagines himself beside her. In one of the depictions, he sees a reflection that he finds disfigured but then realizes that it is his.

- Cinecittà: The author describes the location of the Maritime Hospital at Berck which is in the Pas de Calais. On one occasion that he is being wheeled through the hospital corridors he spots a corner of the hospital which contains a lighthouse which he names Cinecittà.

- Tourists: The author says Berck, the hospital, focused primarily on the care of young tuberculosis patients following the Second World War. It has now shifted toward older patients, which make up most of the hospital's population. He refers to as Tourists those who spend a short time in the hospital following injuries such as broken limbs. For him, the best place to observe this is in the rehabilitation room and the interactions he has with these patients.

- The Sausage: He doesn't pass his dietary test, as yogurt enters his airway, so he “eats” through a tube connected to his stomach. His only taste of food is in his memories, where he imagines himself cooking dishes. One food is the sausage which connects to a memory from his childhood.

- Guardian Angel: The author tells of Sandrine, his speech therapist, who has developed the communication code for him and is helping him regain vocal language. He listens to his daughter, Céleste, his father, and Florence speak to him on the phone but he is unable to reply.

- The Photo: The last time the author saw his aging father was a week before his stroke, when he shaved him. He describes his father, whose calls he receives from time to time, and who once gave him a photo marked on the back, in an odd coincidence, Berck-sur-Mer, April 1963.

- Yet Another Coincidence: The author identifies with Alexandre Dumas' character from The Count of Monte Cristo, Noirtier de Villefort. As this character is on a wheelchair and must blink to communicate, Noirtier might be the first case of locked-in syndrome in literature. The author would like to write a modern take of this classic, where Monte Cristo is a woman.

- The Dream: He recounts a dream in which he and his friend, Bernard, are trudging through thick snow as they try to return to France even as it is paralyzed by a general strike. Then Bernard and he have an appointment with an influential Italian businessman whose headquarters are in the pillar of a viaduct. Upon entering the headquarters, he meets the watchman Radovan Karadzic, a Serbian leader. Bernard tells that the author is having trouble breathing and the Serbian leader performs a tracheotomy on him. They have drinks at the headquarters and he discovers that he has been drugged. The police arrive and as everyone tries to escape, he finds himself unable to move - only a door separates him from freedom. He tries to call for his friends but he cannot speak, realizing that reality has permeated the dream.

- Voice Offstage: He awakens one morning to find a doctor sewing his right eyelid shut, as the eyelid no longer functions and risks an ulceration of his right cornea. He mulls over how, like a pressure cooker, he must contain a delicate balance of resentment and anger which leads him to the suggestion of a play he may base on his experiences, with a final scene in which the paralytic man stands up and walks but a voice says, "Damn! It was only a dream!"[4]

- My Lucky Day: He describes a day where, for half an hour, the alarm on the machine that regulates his feeding tube has been beeping non-stop, his sweat has unglued the tape on his right eyelid causing his eyelashes to tickle his eye, and the end of his urinary catheter has come off and he is drenched. A nurse ends up finally coming in.

- Our Very Own Madonna: The author tells the story of his pilgrimage to Lourdes with Josephine in the 1970s. During the trip, he argued with Josephine repeatedly. Later, while traveling through the town, the two see a statue of the Madonna, the Holy Virgin. He buys it for her although later they know they will separate. He attempts to read the book, The Trace of the Serpent, he notices that Josephine has written a letter on every page, so that collectively they read: "I love you, you idiot. Be kind to your poor Josephine."[4]

- Through a Glass, Darkly: Théophile and Céleste visit the author for Father's Day with their mother, Sylvie, Bauby's ex-wife. They head to the beach outside the hospital. He observes his children but is filled with sorrow as he cannot touch his son. He plays hangman with Théophile while Céleste puts on a show of acrobatics and song. They spend their day on the beach until it is time for his children to go.

- Paris: His old life burns within him like a dying ember. Since his stroke, he has traveled twice to Paris. The first time he went, he passed the building where he used to work as Elle's editor-in-chief, which makes him weep. The second time though, about four months later, he felt indifferent but knew nothing was missing except for him.

- The Vegetable: He recounts the opening to a letter he has sent to friends and associates, about sixty people, which make up the first words of his monthly letter from Berck. In his absence, there are rumors in Paris that he has become "a vegetable", which he wishes to dispel. This monthly letter allows him to communicate with his loved ones, the letters he receives in return he reads himself and keeps like a treasure.

- Outing: Weeks or months have passed since Bauby has ventured outside the hospital. On this day, he is accompanied by his old friend, Brice, and Claude, the person he is dictating the book to. Though the journey is rough on his butt and winding, he keeps moving toward his goal. Meanwhile, he contemplates how his universe is divided into those who knew him before the stroke and all others. Drawing closer to his destination, he sees Fangio, a patient of the hospital who cannot sit so he must remain standing or lying down. His destination ends up being a place that serves french fries, a smell which he doesn't tire of.

- Twenty to One: He tells two stories in this chapter: of an old horse called Mirtha-Grandchamp and of the arrival of his friend Vincent. Over a decade ago, Vincent and he had gone to a race where it was rumored the horse Mirtha-Grandchamp would win. They had both planned to bet on the horse but the betting counter had closed before they were able to make a bet. The horse ends up winning.

- The Duck Hunt: Bauby has hearing problems. His right ear is completely blocked whereas his left distorts all sound that is more than ten feet away. The loud activities and patients of the hospital hurt his ears, but once they are gone, he can hear butterflies in his head.

- Sunday: Bauby dreads Sundays as there as no visitors of any sort, friends or hospital staff, besides the rare nurse. He receives a bath and is left to watch TV, though he must choose wisely as the wrong program or sound can hurt his ears, and it'll be long before someone comes in and is able to change the channel. The hours stretch and he is left to contemplate.

- The Ladies of Hong Kong: He loved traveling and has banks of memories and smells to recall. The one place he has not managed to visit is Hong Kong; he imagines his colleagues there and how the people, presumably superstitious, would treat him.

- The Message: He contrasts the cafeteria population to his side of the hospital. He, mentions a typewriter that sits with a blank pink empty slip. He is convinced that a message will be on it for him one day and he waits.

- At the Wax Museum: He has a dream of visiting the Musée Grévin. The museum has changed a lot and is distorted. Rather than contemporaries figures, the various personnel he encounters in the hospital adorn the museum. He has given them all nicknames. He then goes on to the next exhibit which is a recreation of his hospital room except his pictures and posters on his wall contain stills of people he recognizes. He is then woken by a nurse asking if he wants his sleeping pill.

- The Mythmaker: The author tells of an old schoolyard friend, Olivier, known for his runaway mythomania where he would claim to have spent his Sunday with Johnny Hallyday, gone to London to see the new James Bond film, or been driving the latest Honda.[4] Just as Olivier wove stories about himself, Bauby now imagines himself a Formula One driver, a soldier, or a cyclist.

- "A Day in the Life": He describes the day of his stroke, December 8, 1995. As he traveled to work, he listened to the Beatles song A Day in the Life. Once he leaves work, he goes to pick up his son to take him to the theater but, on the way, his vision and mind blur. He makes it near where his sister-in-law, Diane, a nurse, lives. He sends his son to get her and she takes him to a clinic where he is taken in by doctors. His final thoughts before slipping into a coma involve the night he was to spend with his son and where his son went off to.

- Season of Renewal: It is now September and the author describes the end of summer. Because of speech therapy, he can now grunt a song about a kangaroo. Claude rereads the pages of text that he and his assistant have written together and wonders whether it is enough to fill a book. He closes with, "Does the cosmos contain keys for opening up my diving bell? A subway line with no terminus? A currency strong enough to buy my freedom back? We must keep looking. I'll be off now."[4]

Adaptations

In 1997, Jean-Jacques Beineix directed a 27-minute television documentary, "Assigné à résidence" (released on DVD in the U.S. as "Locked-in Syndrome" with English subtitles), that captured Bauby in his paralyzed state, as well as the process of his book's composition.[5]

Artist/director Julian Schnabel's feature-film adaptation of the book was released in 2007, starring Mathieu Amalric as Bauby. The film was nominated for several international awards and won best director that year at the Cannes Film Festival.[6][7][8][9]

In 2019, The Dallas Opera was awarded a National Endowment for the Arts grant to commission The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, an opera based on Le Scaphandre et le Papillon by Jean-Dominique Bauby which will be composed Joby Talbot with a libretto by Gene Scheer.[10][11]

References

- "Elizabeth Day interviews ghost-writer Claude Mendibil". the Guardian. 2008-01-27. Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- Thomas, Rebecca. Diving Bell movie's fly-away success, BBC, February 8, 2008. Accessed June 5, 2008.

- Mallon, Thomas (June 15, 1997) "In the Blink of an Eye - The Diving Bell and the Butterfly," The New York Times. Retrieved April 8, 2008.

- Bauby, J. (1998). The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (First Vintage International ed.). New York: Random House, Inc.

- "film-documentaire.fr - Portail du film documentaire". www.film-documentaire.fr.

- "Cannes Winners: Stark Abortion Drama Tops". www.altfg.com.

- Academy Awards Database Archived 2008-09-21 at the Wayback Machine

- "Film Awards". www.bafta.org. 31 July 2014.

- HFPA Awards Database

- "Fourteen North Texas Arts Groups Earn $400,000 In Grants From The NEA". www.artandseek.org. 14 February 2019.

- "Fiscal Year 2019, First Round, Artistic Discipline/Field List" (PDF). www.arts.gov.

External links

Reviews of The Diving Bell and the Butterfly: